We are halfway into the month of January, and already the year 2015 has unleashed unspeakable violence – whether we look to the horrific massacre of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists, police officers, and Jewish hostages in Paris, France or to the unimaginable carnage that left 2,000 villagers dead in the northeastern region of Nigeria. Both attacks were fueled by radical Islamists, including the infamous Boko Haram, who kidnapped over 200 schoolgirls last year, an act that helped launch the widely popular #BringBackOurGirls hashtag on Twitter. Yet, international outrage has galvanized massive support for the Charlie Hebdo victims with a #JeSuisCharlie movement rising to protect freedom of speech and other beloved Western principles, while a lesser movement is struggling valiantly to promote #AfricanLivesMatter, politically connecting this sentiment to another popular hashtag: #BlackLivesMatter.

While some may wish to de-racialize these narratives with the so-called colorblind #AllLivesMatter, the unequal attention to these world events simply reinforce that not all lives matter, least of all those who are not afforded the white privilege of the French journalists who were unjustly murdered – no matter what one may have thought about their questionable cartoons that seemed to racialize its French minority population of Muslims and people of color. Nonetheless, the memorialization of Charlie Hebdo reinforces how much more white lives are valued. That some took to Twitter to create #JeSuisAhmed, in memory of the Muslim police officer also killed in the attacks, is a gesture reminding us that the value of marginalized peoples is never taken for granted. As Noah Berlatsky noted, “Who is remembered and who is memorialized has everything to do with race, with class, with where you lived and who, in life, you were.”

Of course, we can rationalize inequalities in media coverage – why the “world” seems to care about France over Nigeria, or why English speakers are questioning whether or not the Charlie Hebdo cartoons are “racist” or not, or even if we should criticize murdered victims who can no longer speak for themselves. Perhaps the violence in Africa seems more “routine,” in comparison to what takes place in Europe, hence more focus on Paris. And perhaps English speakers are “misinterpreting” Charlie Hebdo cartoons as “racist” and “Islamaphobic” since we are not translating the French correctly. Yet, such reasons given seem to suggest an unequal flow of information, as if “African violence” and “Muslim irrationality” are the only acceptable explanations for why violence happens (and why we should care more about France than about Nigeria).

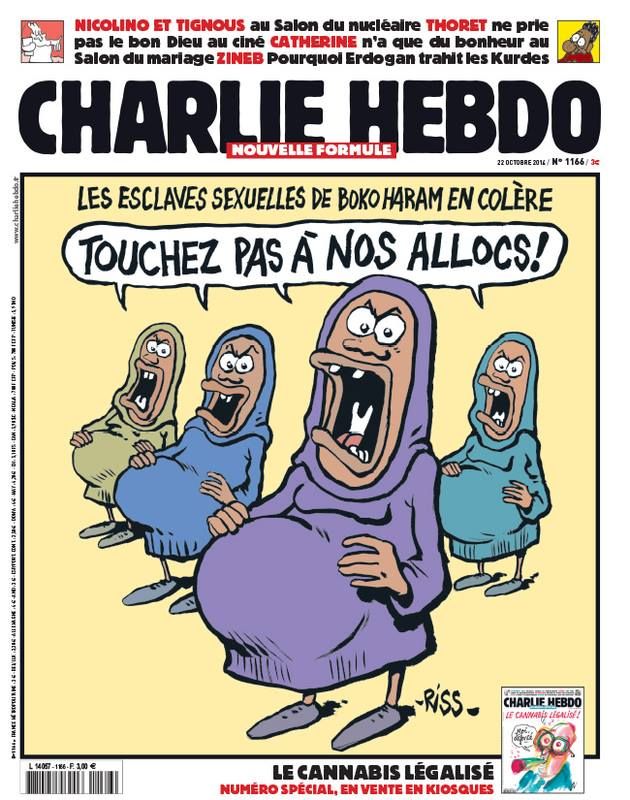

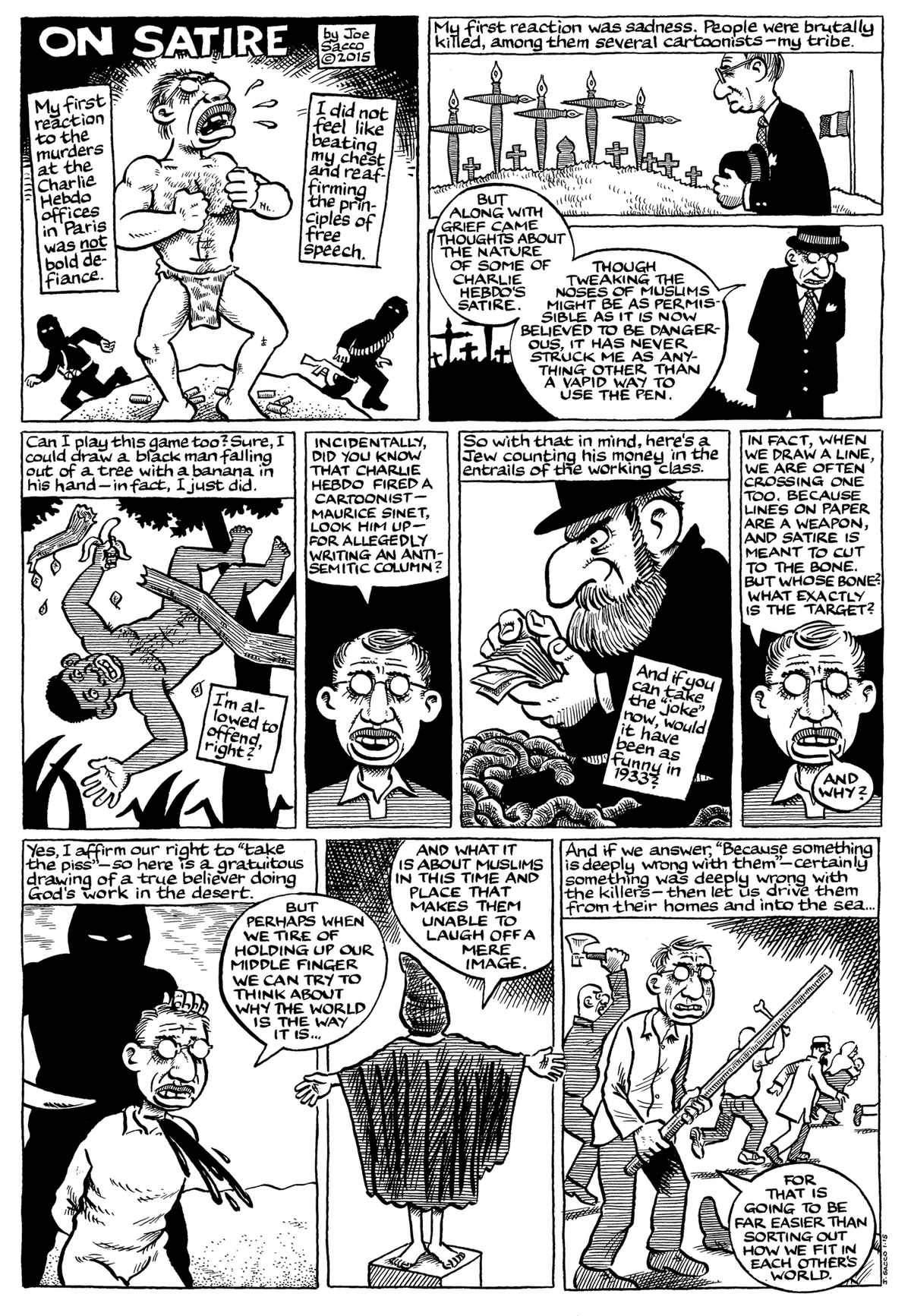

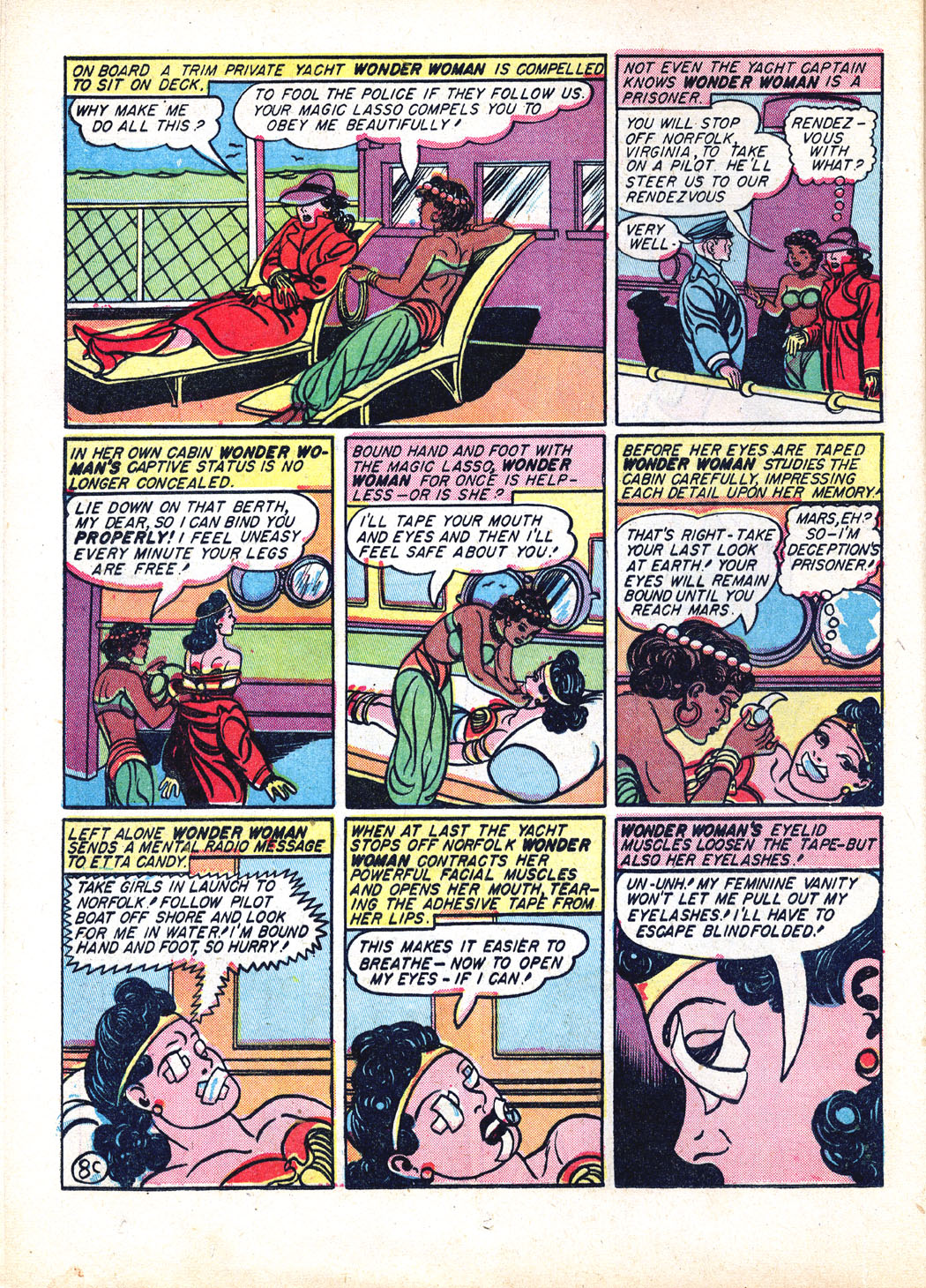

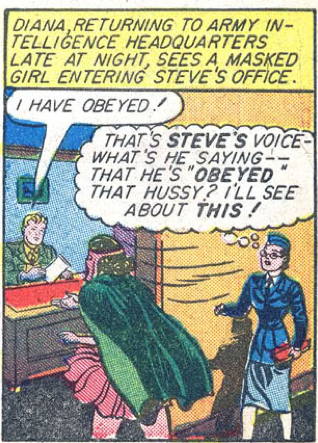

However, it is to these points that I want to take note of a particular cartoon featured in Charlie Hebdo, one that has drawn the most criticism for the publication’s racial politics. Here I refer to the cartoon depicting Boko Haram’s kidnapped girls in Nigeria.

As French-speaking translators have informed us, the text reads: “Boko Haram’s sex slaves are angry,” while the visual depicts head-covered girls yelling “Don’t touch our welfare!” And as Max Fisher suggests, the cartoon functions on two layers: “What this cover actually says … is that the French political right is so monstrous when it comes to welfare for immigrants, that they want you [to] believe that even Nigerian migrants escaping Boko Haram sexual slavery are just here to steal welfare. Charlie Hebdo is actually lampooning the idea that Boko Haram sex slaves are welfare queens, not endorsing it.”

Such explanations may provide us with contexts and subtexts, but they are nonetheless steeped in apologia, conveniently overlooking the visually demeaning drawing of the girls or the racialized subtexts associated with African or Orientalist sexual savagery, coupled with a transnational narrative of black and immigrant women unfairly using the state’s resources (how interesting that conservatives here and abroad tend to speak the same racial language). Regardless of Charlie Hebdo’s own politics, the visual narrative recycles stereotypes and could easily be appropriated for white supremacist narratives.

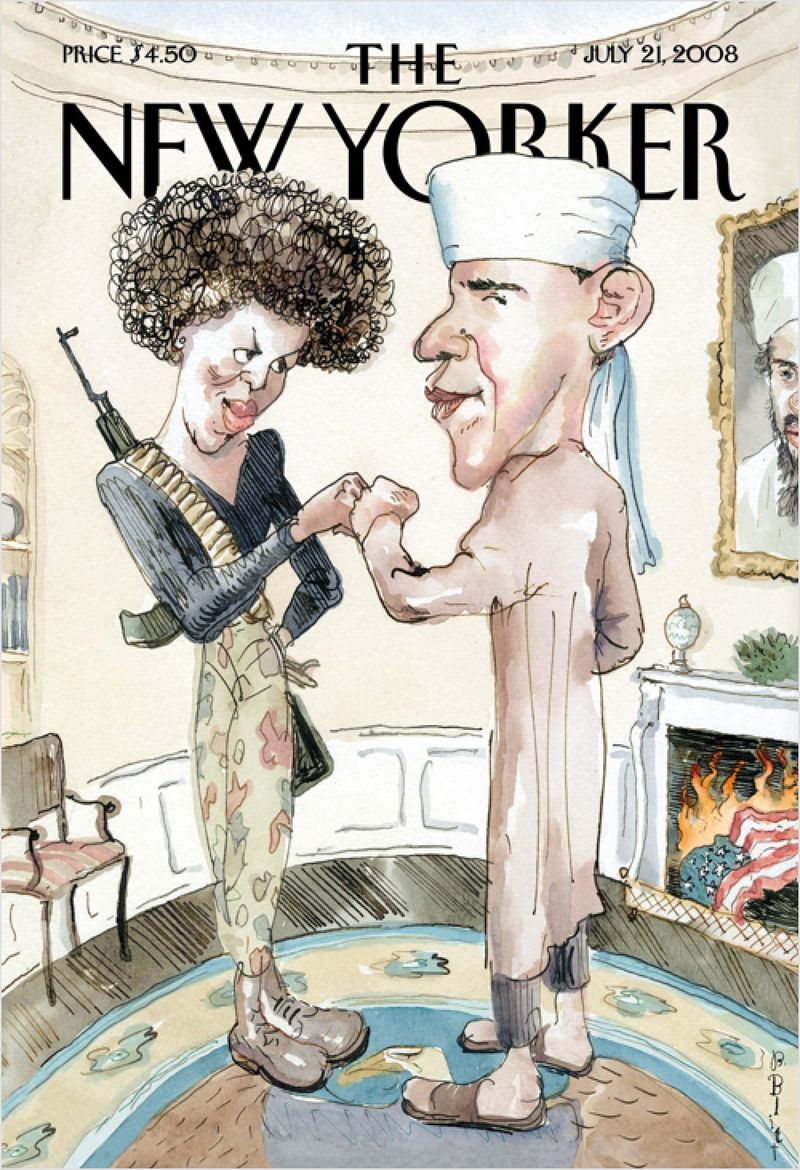

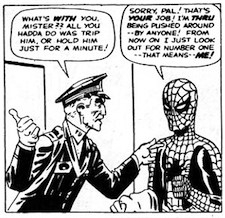

Fisher juxtaposed this satire alongside another parody – the New Yorker’s satirical takedown of Republican fears of the Obamas’ “secret black nationalist Muslim” plans during the 2008 presidential campaign.

Fisher then argued that “most Americans immediately recognized that the New Yorker was in fact satirizing Republican portrayals of the Obamas, and that the cover was lampooning rather than endorsing that portrayal.” This really highlights the problem of unspoken white privilege and power, as Fisher conveniently forgets that the New Yorker too came under attack – especially from communities of color who saw in the satire a failed use of racial imagery to poke fun at racism.

Why is it that the black or brown body becomes the vehicle for racial humor when the objects of ridicule – the white people presumably targeted for their racial bigotry – remain invisible in these satirical narratives? When recycling racial stereotypes – which both The New Yorker and Charlie Hebdo have done – do linguistic texts and subtexts hold the same equal power as the visual text, which holds heavier historical weight? Not all members of society (specifically communities of color who continue to feel their marginality in various social institutions) read these visual narratives in the same way. After all, if even in the U.S. certain Americans didn’t find the New Yorker cover funny – though we speak the same language and have access to the same cultural and political frames of reference – then what gets “lost in translation” when exposed to other local texts, contexts, and subtexts? Whose voices remain silent?

I specifically think of this when considering the actual creation of the Charlie Hebdo Boko Haram cartoon. I have a difficult time imagining a black woman cartoonist of any nationality – French, British, American, Nigerian – creating such a cartoon in jest. I also have a hard time seeing such a woman hired by the staff at Charlie Hebdo, and even if she were and found the courage – as the sole “token” black woman at the paper – to speak up to her colleagues and say, “Hey guys, this cartoon isn’t funny, and here’s why,” would her white male colleagues let her speak? Would they hear what she had to say? Would they drown her out with their insistence on “free speech” and “the right to offend,” or would they sincerely listen to suggestions on how their takedown of French political right racism could be, you know, clever (as racial stereotypes never are) and how the offense could be more effective in a “punch up” or “punch across” rather than “punch down” kind of way?

And therein lies the problem: the unequal flow of perspectives and unequal participation. Whether we point to white conservativism or white liberalism, these narratives hold cultural weight, even those that insist – because they may be on the “right” side of antiracism politics – that they could never get their racial politics wrong, even when they don’t interrogate the ways that they may hold or perpetuate racial privilege and power. The views of others remain in the margins, including our pain and suffering.

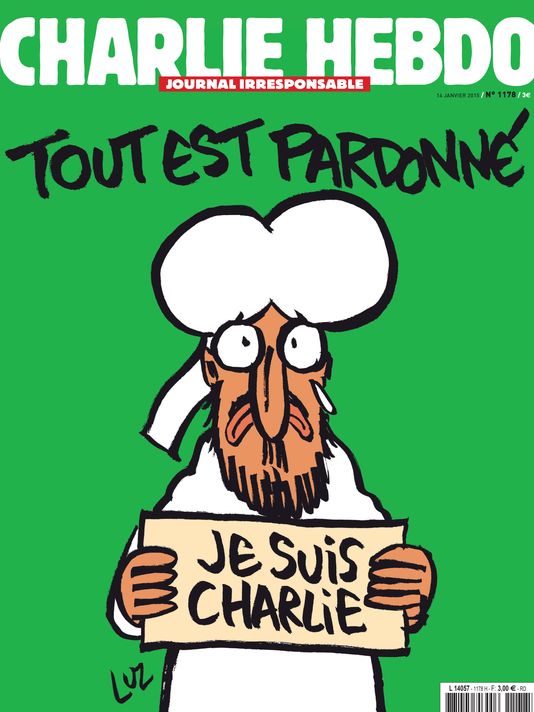

Charlie Hebdo’s latest cover features the Prophet Muhammad holding a “Je Suis Charlie” sign with a single tear rolling down his cheek as the text reads “All if forgiven”; the satire is quite apt and heartfelt and, most importantly, captures a kernel of truth in the moment.

On the other hand, the Arab stereotyping of the prophet distorts truth and has reconstituted him as a French creation of the cartoonists’ own making, no longer connected to the religion or culture that prompted their satire in the first place. That is the nature of stereotypes, which have the effect of erasing altogether the very peoples and cultures they were intended to represent.

In closing I want to return to the scene of Nigeria, in particular Boko Haram’s alleged use of a ten-year-old girl to carry out a suicide-bombing attack. I can’t help but think this is the most cynical ploy and a deadly play on satire. What else is Boko Haram expressing but their utter contempt for and mockery of the West’s “Bring Back Our Girls” movement? They implicitly know that our rhetorics are empty and our raced and gendered messages constantly show our disregard for women and girls of color. They know that black girls’ bodies will only serve as mere objects of parodic visuals or Twitter hashtags without any real actions demonstrating that their lives matter. Somehow, these global understandings of whose lives matter don’t get lost in translation.

________

For all HU posts on Satire and Charlie Hebdo click here.