Few comics in the last year have elicited as much critical attention as Robert Crumb’s The Book of Genesis Illustrated. Most of these notices have been positive with a number of publications affirming Crumb’s status as a cartooning god. Such has been the adulation that even the most ardent Crumb enthusiasts no longer clamor for more recognition but are now asking for deeper and more contemplative readings of the comic. Consider Jeet Heer in a recent post at Comics Comics:

“As I’ve mentioned before, I’ve been disappointed by the critical response to Crumb’s Genesis book. It is not so much a matter that the book hasn’t won enough praise, but rather that the critics, with a handful of exceptions, haven’t had the intellectual resources to tackle the challenge presented by Crumb’s handling of the Bible. Ideally, the critics of the book should be well-versed in both comics and Biblical scholarship.”

Heer’s statement suggests that Crumb’s book is of such learned complexity that only individuals of the greatest experience and intellect would be able to do it justice. Suffice to say, I found this statement to be at odds with my own experience with the comic which I felt offered more superficial pleasures.

In order to ascertain the truthfulness of this and various other statements in praise of Crumb’s comic, I’ve decided to examine his handling of what may be the two most famous chapters in Genesis, namely chapters 2 and 3 which concern the creation and fall of man. The importance of these two chapters in the context of Judaism and Christianity is such that their substance is widely known even by those with only a cursory knowledge of Genesis. They have also been the subject of innumerable explorations and appropriations in art, film, poetry and literature. These factors will make the ascertainment of the extent of Crumb’s achievements in The Book of Genesis that much easier.

***

In some recent blog comments, Heer advised his readers that “Crumb was performing exegesis through his adaptation and thus is part of a long tradition of Biblical commentary”. In another posting he writes that The Book of Genesis “deserves to be seen not just as an important work of art but also a significant commentary on the Bible.”

Of course, such an adaptation could not be anything else. For one, the practice of illustration itself presupposes the act of interpretation [exegesis: from Greek, from exegeisthai to interpret, from ex-1 + hegeisthai to guide]. The artist must provide expression, posture, dress, setting and reaction where the text is silent. He may even choose to provide a useful contradiction between word and imagery if he is so moved. We see this in the plethora of considerably less elevated Bible-related adaptations Charles Hatfield lists in his survey of a Genesis exhibition at the Hammer museum. Secondly, as the noted scholar, critic and translator, Robert Alter, states in his initial comments on Crumb’s book in The Nation:

“I stress that it is an interpretation, because the extremely concise biblical narrative, abounding in hints and gaps and ellipses, famously demands interpretation.”

Rather, the issue at hand here is whether Crumb’s adaptation of Genesis is “significant”, that is a work which cannot be ignored in any consideration of the art or literature connected to the Bible.

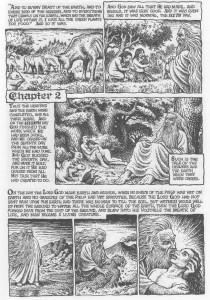

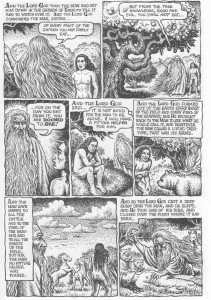

To be sure, the bulk of the praise extant has dwelt upon the artist’s reputation and his distinctive execution. Henry Allen of The Washington Post can hardly contain himself at the thought that the pope of impiety, political incorrectness and hedonism has decided to take on the Bible and God. Alter embraces this as well and has the following to say about the opening verse of chapter 2 of The Book of Genesis:

“Perhaps the most winning aspect of Crumb’s Genesis is its inventive playfulness… God’s resting on the seventh day of creation is shown by his sitting with his eyes closed, fatigued, his back against one of the trees of the Garden, while naked Adam and Eve in the background cuddle together in sleep.”

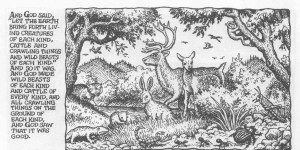

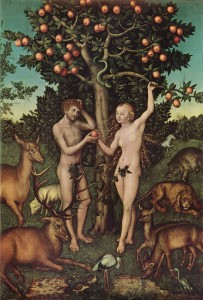

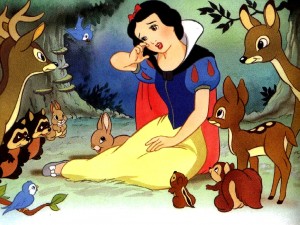

The scene is, of course, not so subtle satire; a reimagining of that unblemished garden as a kind of Disney cartoon (and every bit as ridiculous and fictional) with Bambi, Thumper and Faline in attendance.

____

____

The woodland creatures who espy the sleeping creator bear comparison with those which surround Snow White in her most popular incarnation. This gently mocking tone reasserts itself periodically throughout Genesis.

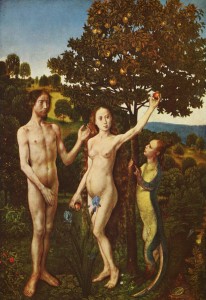

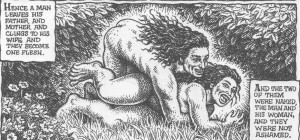

Crumb’s oft cited depiction of pure sexual disinhibition towards the close of chapter 2 is another example of this frolicsome spirit which in this instance seems almost self-referential in its longing.

[Gustav Klimt’s Adam and Eve (unfinished)]

[Fritz Comes on Strong”, 1965]

[Cave Wimp”, 1988]

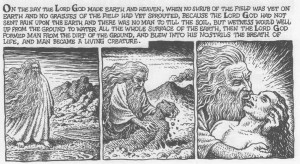

As for the artist’s rendering of the creation of Adam, it has some similarities to that found in Basil Wolverton’s The Bible Story, a connection elaborated upon by Charles Hatfield at Thought Balloonists.

This solution was not an uncommon one during the Italian Renaissance, here made fresh by showing the stages in this act, in particular the breath of life given to Adam (the word “breathed” or “blew” here suggesting the intimacy of a kiss). Crumb’s adaptation is also notable for showing Adam in his clay-like state, a reminder of the Egyptian (see The Hymn of Khnum and Hekat) and Mesopotamian (see Enki & Ninmah, and Bel) myths which carry the same motif.

As articulated in his short commentary found at the end of The Book of Genesis, Crumb is particularly interested in these ancient tales of creation and periodically inserts them while neglecting to emphasize the many internal consistencies, dilemmas and word plays in the Biblical narrative. Thus, for example, the “dirt of the ground” is linked to pagan tradition and not to a play on the words “man” (adam) and “ground” (adama) where “man is related to the ‘ground’ by his very constitution (Genesis 3:19), making him perfectly suited for the task of working the ‘ground,’ which is required for cultivation…his origins also become his destiny” (Kenneth A. Matthews).

The stated “literalness” of Crumb’s adaptation as well as its generally bland imagery will lull many readers into the false impression that Genesis intends a deep consideration of centuries old biblical scholarship. It doesn’t, an important point which I will address in more detail later.

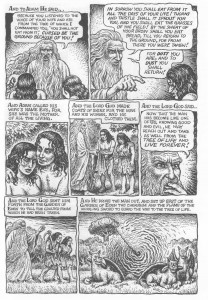

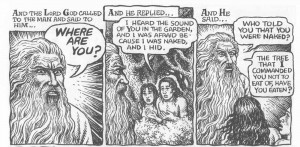

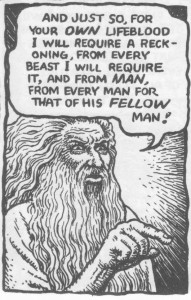

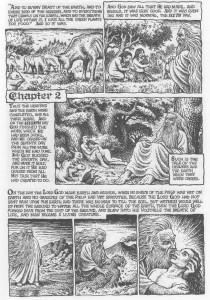

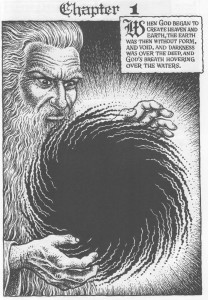

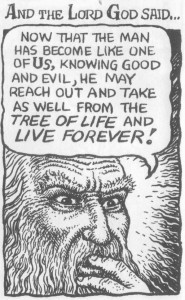

What follows is God’s prohibition and warning concerning the consumption of fruit from the tree of knowledge. The Lord’s brows are knit, his figure towering over Adam. It is interesting to note the number of times Crumb portrays God from this standpoint in his comic; that of a person standing at the edge of reality who seems of human proportions, but who then takes on the space and terrifying air of something other worldly when provoked.

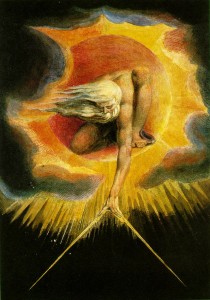

There is the instance of God’s act of creation…

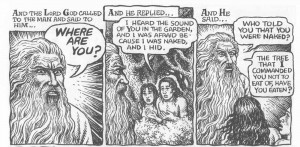

…his anger as he calls to Adam & Eve who are seen hiding in some shrubbery…

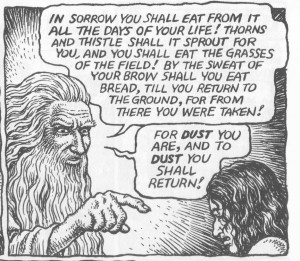

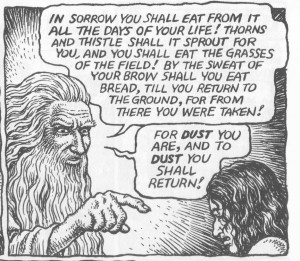

…his curse on the ground and Adam…

[Genesis 3:19]

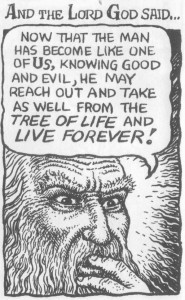

…his cogitations concerning the ambitions of man…

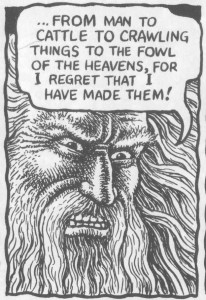

…his decision to invoke the great flood…

…and his sanction against murder.

In explication of his choice to so portray the Almighty, Crumb writes:

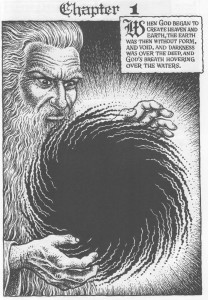

“After closely reading the beginning of the Creation, I suddenly imagined an ancient man standing on the shore of a sea, and gazing out at the horizon, and seeing only water meeting the sky.”

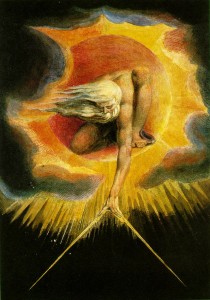

Much criticism has focused on Crumb’s use of the traditional image of a bearded old man to depict God. There are certainly glaring problems with this. For one, it conjures up all kinds of unflattering comparisons to his artistic forebears.

It also conveys an all too facile understanding of Adam being made in the “image of God” (imago dei), whether this is rooted in the theories and debates surrounding the terms “likeness” and “image” (e.g. in the writings of Irenaeus and Thomas Aquinas), the existential and relational readings of Karl Barth or the functional readings which altogether dispense with the idea that the “image” must consist of non-corporeal features (i.e. the “image of god” as seen in man’s dominion over the earth and animals). This is but one indication that Crumb’s journey through Genesis was more personal and instinctive than cerebral.

Hence we have Marc Sobel’s complaint that “part of the problem [he] had with this adaptation [was] the overly literal interpretation and the complete lack of insight about the actual ideas underlying Genesis:

“Thus, the depictions of God as an old man, the creation story, etc. that you [Derik Badman] commented on represent a very childish understanding of Genesis. That would be fine if this were a children’s book, but the problem is that, by presenting the entirety of the dense text… no child will be able to penetrate this book either. Thus, its an interpretation doomed to disappoint any potential audience other than fans of Crumb’s art.”

On the other hand, some might argue that Crumb’s portrayal of the creator (fleshy, interactive and emotional) is an acknowledgment of the capricious Mesopotamian gods the artist is so enamored of. Crumb had the following explanation concerning his approach in his interview at Vanity Fair:

“I had several different approaches to making God. One was a tall thin man with no beard and another was a young looking man with long straight hair that looked more like an angel than a god. He had pupil-less eyes that were beaming light. But I decided to go with the standard, severe patriarchal God. It just felt like the right choice. That just seems to be what the God of Genesis is all about. He’s older than the oldest patriarch.”

Crumb’s almost anti-intellectual approach to Genesis continues to pose difficulties throughout the rest of these two chapters.

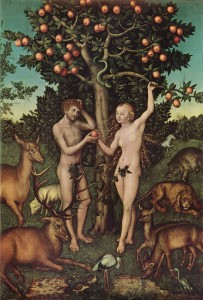

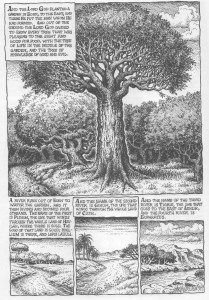

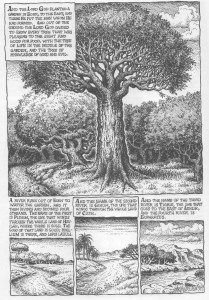

While few would question the rigor with which the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is drawn, it remains at best only a fruit bearing tree. One might view the central image of the tree of life (many branched, filled with knots and ramrod straight) as a representation of the masculine ideal and the tree of knowledge in the background as the curvaceous and deadly feminine, but there is little beyond this to recommend it.

What we don’t find in these illustrations is any evidence of the speculative richness the idea of the tree of knowledge has evoked through the ages; be they the ideas concerning sexual awareness proposed by Ibn Ezra, the capacity for moral discrimination, the granting of paramount knowledge or the bestowal of a divine wisdom. All that we find in The Book of Genesis is a personal mythology influenced in sections by the somewhat discredited theories of Savina Teubal (which I should add is still preferable to the alternative of unthinking transcription; see R. C. Harvey’s summary of this as well as another feminist perspective).

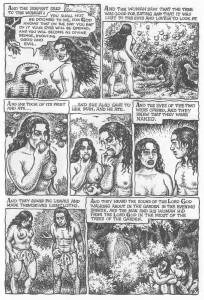

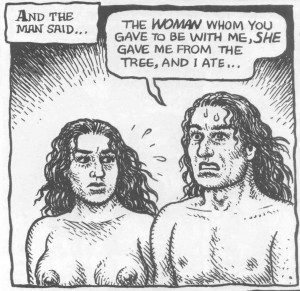

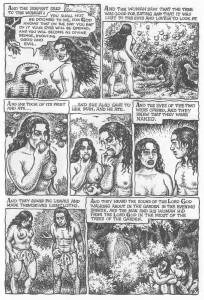

In much the same vein, the encounter with the serpent in Genesis chapter 3 is reduced to a flaccid conversation with a walking reptile. Adam is absent throughout this version of events, though the presence of the plural form of “you” in 3:1-5 suggests he is with Eve but not deceived like she is. Crumb sticks to his vow of straight illustration, refusing to explore the reasons for Adam’s acquiescence despite his absence from the serpent’s exchange with Eve in this account. Genesis Rabbah 19.5, for example, posits the administration of cold logic and tears by Eve, which while clearly offensive in this day and age would still be better than this bland reading.

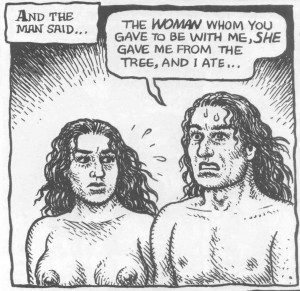

Eve’s look of consternation at Adam’s betrayal and shifting of blame (he is actually indirectly blaming God) in Genesis 3:12 is better for it shows at least some artistic involvement with the terse text.

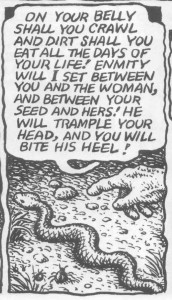

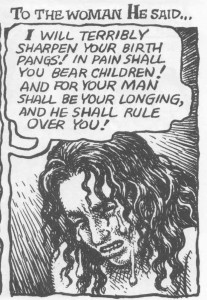

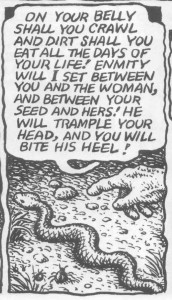

The entirety of God’s judgments from Genesis 3:14 to 19 are depicted without comment or analysis. The artist’s hand here is as distant as a machine-operated drafting tool. In response to Genesis 3:15 (“And I will put enmity between thee and the woman, and between thy seed and her seed; it shall bruise thy head, and thou shalt bruise his heel.”) we get a somewhat cursorily drawn snake wriggling away. It is common knowledge that Christians look upon these verses as the protoevangelium (for example, some church fathers saw the “woman” here as the virgin Mary and the “seed” as representing the church and/or Christ in particular) while Jewish commentators sometimes view the “seed” as a metaphor for humankind.There is little evidence of a response to these or any other interpretations here.

All this can be easily explained by constraints of time, space and artistic lassitude, but it should also be noted that Crumb (a self-proclaimed Gnostic) has little interest in Genesis as a religious or sacred text, a tremendous hindrance in adapting a book which has been largely interpreted in that context. As he clearly states in his interview at USA Today:

“To take this as a sacred text, or the word of God or something to live by, is kind of crazy. So much of it makes no sense. To think of all the fighting and killing that’s gone on over this book, it just became to me a colossal absurdity. That’s probably the most profound moment I’ve had — the absurdity of it all.”

Nor is there any suggestion that he took it upon himself to find out why the book in question has remained coherent and relevant to a multitude of very rational artists, philosophers and scientists through the ages. One hardly needs to believe to read closely and with an intent to understand. Thus stripped of emotional and mental investment, Crumb’s Genesis frequently degenerates into half-digested pabulum.

As would be expected, these issues have generated a modest amount of discussion online. David Hajdu writing in The New York Times adopts a more religious approach in his disagreements with Crumb and The Book of Genesis:

“For all its narrative potency and raw beauty, Crumb’s Book of Genesis is missing something that just does not interest its illustrator: a sense of the sacred. What Genesis demonstrates in dramatic terms are beliefs in an orderly universe and the godlike nature of man. Crumb, a fearless anarchist and proud cynic, clearly believes in other things, and to hold those beliefs — they are kinds of beliefs, too — is his prerogative. Crumb, brilliantly, shows us the man in God, but not the God in man.”

Points with which Dan Nadel of Comics Comics disagrees:

“I can’t see how, as an irreligious reader, you come away with that interpretation. I mean, there are two conflicting accounts of creation. Not exactly orderly. Also, Crumb is not, as far as I know, an anarchist, but he is, by his own account, spiritual. Which is to say, Crumb seems to be exploring the sacred. Maybe not Hajdu’s sacred, but sacred nonetheless.”

Hajdu wants Crumb to add a spiritual dimension to his reading of Genesis, something which is clearly irrelevant in the context of creating a fine adaptation based on modern day archaeology or biblical scholarship. Nadel seems more offended by Hajdu’s suggestion that Crumb lacks a certain spirituality which is equally of no consequence to this project, since Crumb is far more interested in the historical and mythological aspects of Genesis (i.e. not a journey of the soul but one of personal discovery).

***

It should be understood that while in-depth exegesis of the sort discussed above is frequently beyond the means of the single image (in painting for instance), it is certainly not unimaginable in the context of comics.

Failing to see this, Alter complains that “the foreclosure of ambiguity or of multiple meanings is intrinsic to the graphic narrative medium, and hence is pervasive in the illustrated text…The image concretizes, and thereby constrains, our imagination.” Then referring to the example of Genesis 9:20-27 where Ham sees “the nakedness of his father” he states:

“The most innocent reading, which is the one that Crumb chooses to follow, is that Ham simply saw his father exposed, thus violating what those who adopt this view assume was a grave taboo in Israelite society. This reading may well be right, though the report that when Noah wakes from his wine “he knew what his youngest son had done to him” might suggest that an act more palpable than mere seeing was perpetrated. Some interpreters in late antiquity, encouraged by these words and probably thinking of the Zeus-Chronos myth, imagined that Ham castrated his father, though this notion has always seemed to me rather unlikely. My own preference as a reader is to relish the shimmer of murky possibilities, including the more lurid ones, even if I am left without a concrete or confident picture of what actually happened. Pictorial representation forces you to decide one way–which, however appealing or plausible that way may be, imposes a limit on the story told in words.”

What Alter fails to realize is that the presentation of a host of concomitant possibilities is not beyond the reach of a comics adaptation. This is true even if pictorial representation will never possess the elusiveness, comparatively speaking, of spare sentences on a page. If there is a weakness here, it lies with the choices and abilities of the artist not the medium.

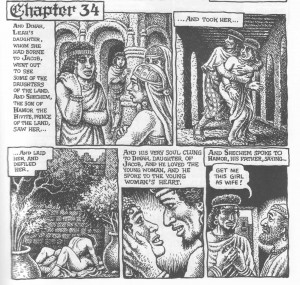

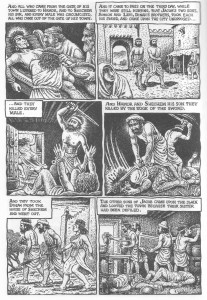

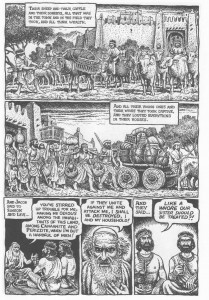

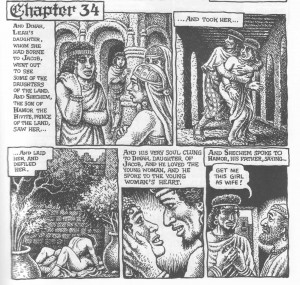

It may be that a trace of this hoped for ambiguity can be found in one of Crumb’s more successful passages in The Book of Genesis, one which Alter bring ups for special mention in his review. Genesis chapter 34 tells the story of Dinah (the daughter of Leah), her defilement by Shechem (the son of a Hivite Prince), and the terrible vengeance wrought on his people by the sons of Jacob.

The story is rich in possibilities: the ethical questions are right at the forefront, the underlying textural discourse plentiful.

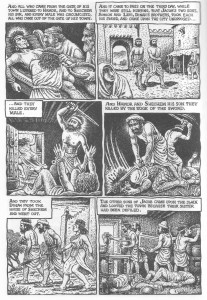

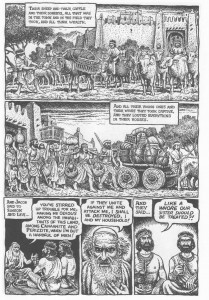

There is the question of the narrator’s attitude (for, against or ambivalent) towards the events, the episode here being a mere prelude to a host of base acts perpetrated by Jacob’s sons until they encounter Joseph in Egypt. There is a cohesion which is implied in this arc that suggests a descent into moral degeneracy before a final redemption in the land of the Pharaohs. We also have the views of some early Jewish interpreters who saw divine sanction in the acts of Simeon and Levi (the prime movers in the slaughter of Shechem’s people). The Book of Jubilees, for instance, states that “judgment is ordained in heaven against them that they should destroy with the sword all the men of the Shechemites because they had wrought shame in Israel.” We also learn by way of Jubilees that Dinah was a girl of 12, a “fact” which has been used to justify the vengeful extermination of the Shechemites and to rehabilitate the victim, Dinah (by Luther; she had been used by early Christian interpreters as an example of idle curiosity and lust).

Lyn M. Bechtel’s suggestion that Dinah was not raped is alluded to but not confirmed in Crumb’s comic. Her tears in the penultimate page of The Book of Genesis have been taken for those of sorrow though it is not so hard to imagine them as tears of relief. In Crumb’s rendition of Genesis 34:3 (“And his very soul clung to Dinah, daughter of Jacob, and he loved the young woman, and he spoke to the young woman’s heart.”), an enraptured Shechem looks down on a woman who is caught somewhere between ardor and hopelessness (most reviewers have chosen to see the former). The greatest delights to be found in this section of The Book of Genesis may lie in this subtle play of facial and bodily expression.

This has some connection to a short comment by Tim Hodler (at Comics Comics) who takes a different tack in his response to Alter’s criticism stating that:

“Alter doesn’t then go on to recognize that the choices Crumb makes enable an entirely new set of ambiguities and artistic effects that aren’t present in the original text, and make the book worth evaluating as its own entity, and not strictly as a one-to-one translation.”

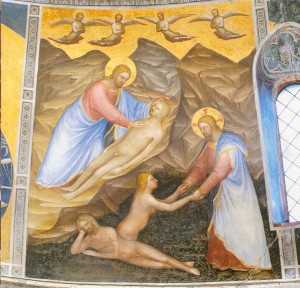

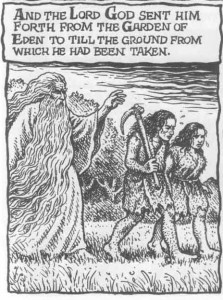

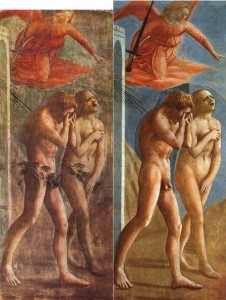

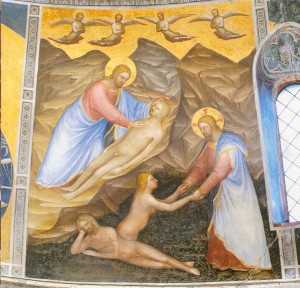

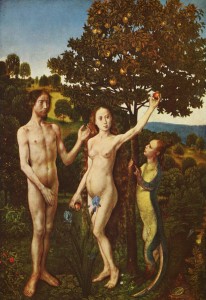

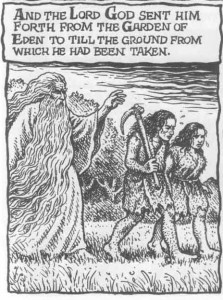

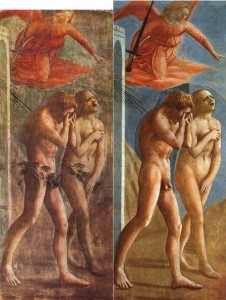

It must be said, that this an argument which I find of somewhat limited use in relation to The Book of Genesis, for the comic largely conforms to the circumscribed borders of traditional illustration impugned by Alter. To be more precise, the “effects” Crumb presents his readers with are considerably poorer than those suggested by the text and subsequently developed upon by scholarship. A number of reviewers have strayed on the side of leniency in considering these issues, not once remarking on the mere utility of Crumb’s choices. Alter who is sometimes cited as being unduly critical towards the end of his essay was in fact being inordinately kind. He censures Crumb for the “hackneyed” depiction of “God as an old man with a white beard” but then compares his drawing of the expulsion of Adam and Eve to Masaccio’s fresco in The Brancacci Chapel in Florence without comment.

___

___

[Right: The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden by Masaccio]

Even those possessed of untutored eyes should be able to see the difference in ability and insight at work here. Masaccio’s Expulsion may be deficient in textural fidelity but its spiritual immersion cannot be disputed. The rigidity of Crumb’s chosen style in The Book of Genesis makes it difficult (he does succeed occasionally) for him to adequately convey anguish, pain or psychological depth in isolation from the text.

I suspect much of this critical kindness is due to a barely realized condescension towards both form and artist. Thus we find the following account in Alter’s review:

“When some chapters of the book were published in The New Yorker in June, a few people with whom I have spoken about them expressed disappointment. Just the same old R. Crumb, they objected: he has not succeeded in developing a visual style that is adequate to the power of the biblical text. Such criticism does not seem to me justified. Crumb has always been an artist with a single style, a distinctive and emphatic one–in this regard as in others he is certainly no Picasso; and so it should neither surprise nor disappoint us that he has used his style to interpret the Bible.”

It is clear from these lines that Alter’s conception of the possibilities of comics and one of its greatest cartoonists is very low indeed. It is impossible to be disappointed if we expect so little.

In fact, in terms of sheer technique, there is nothing in Crumb’s earlier adaptations which can compare with The Book of Genesis. The amount of detail and rendering lavished on each page dwarfs virtually any other in Kafka for Beginners for example. Yet compared to some of this earlier work (such as “The Religious Experience of Philip K. Dick” or his excerpt from Boswell’s London Journal 1762-1763), it suffers from a certain stifling of the imagination. The Boswell adaptation proved a success for two important reason. Firstly, its length (the comic is only five pages long and the simple but fascinating artistic counterpoint at work would have become tedious at a greater stretch) and, secondly, the perfect alignment of subject and adapter.

As with his adaptation of Genesis, Crumb tailored his presentation to fit the elegant but ribald narration; the scenes are proffered at a discrete distance and only periodically punctuated with close-ups of Boswell’s excesses. This is in stark contrast to the paranoia and claustrophobia of the Philip K. Dick adaptation which is marked by subjective phenomena, mystical emanations and frank representations of insanity. Neither of these adaptation bring a substantial amount of analysis to the text but create frisson by way of ironic juxtapositions and personal proclivities. These comics suggest that Crumb’s gifts do not lie in deep inquiry or inquisition but in his idiosyncratic approach; his talent for revealing the extremes of human behavior. Jeet Heer identifies another engaging aspect of Crumb’s art when he writes that:

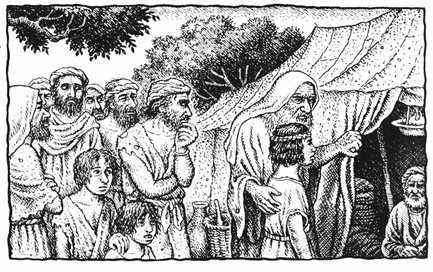

“…Genesis is a book about bodies, a book where men and women constantly grapple with one another, where a servant swears an oath by putting his hand under his master’s thigh, where even angels are threatened with sexual violation. Crumb has long been the preeminent cartoonist of the body. His women are notoriously full-figured, with ample butts and protruding nipples (a motif he uses in this book). But more significantly, the bodies he draws—whether they are quivering or standing still, dancing or drooping—have a visceral impact few artists can match. That’s why he was the perfect cartoonist to illustrate the Book of Genesis…”

A survey of the reviews online would suggest that it is these elements which critics have derived the most pleasure from as far as The Book of Genesis is concerned. I would suggest, however, that this is mean recompense for a full engagement with the intellectual treasures of Genesis. This explains why any suggestion (made in all seriousness in the comments of a recent review) that Alter would feel threatened (the words used are “nervousness” and “professional jealousy”) by Crumb’s awful biblical scholarship is laughable if not symptomatic of a deranged comics provincialism.

As Robert Stanley Martin indicates in his disappreciation of The Book of Genesis, this project (Crumb’s largest to date) cannot be accounted a success even if viewed purely as an act of storytelling. In fact, it conspicuously reveals the artist’s limitations as far as long form works are concerned:

“The overwhelming problem with Genesis is that Crumb doesn’t seem to have thought it through as a dramatic piece. The scenes are not played off each other for dramatic effect, and he doesn’t imagine the characters as distinct, idiosyncratic personalities whose interactions are greater than the sum of the parts…The refusal to see the project as a challenge in terms of orchestrating dramatic choices led him to repetitiously wallow in hackneyed treatments of the material, with most of the clichés of his own making.”

Crumb can be seen as a master of bizarre and transgressive imagery; a self-lacerating maniacal comedian; or a lewd, boisterous and cynical poet of modern living but his personality and disposition have lent themselves poorly to this undertaking. The individuals who are likely take the most satisfaction from this book will be those with a prior interest in comics. It is, after all, a work by a cartoonist of immense stature in the field. If this book does stand the test of time, it will be largely on that basis. For those with a serious interest in the original text and the rich tradition of biblical illustration, on the other hand, Crumb’s comic can only be seen as a well crafted curiosity.

__________

__

Update by Noah: This has started an ongoing series of posts on Crumb’s Genesis. You can see them all here.