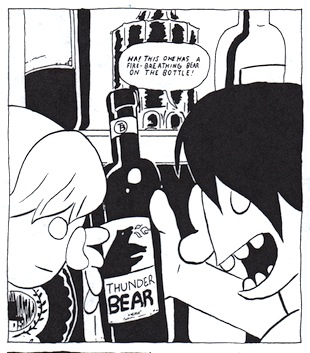

Panel from Sean K’s ‘My First Panic Attack,’ 2011

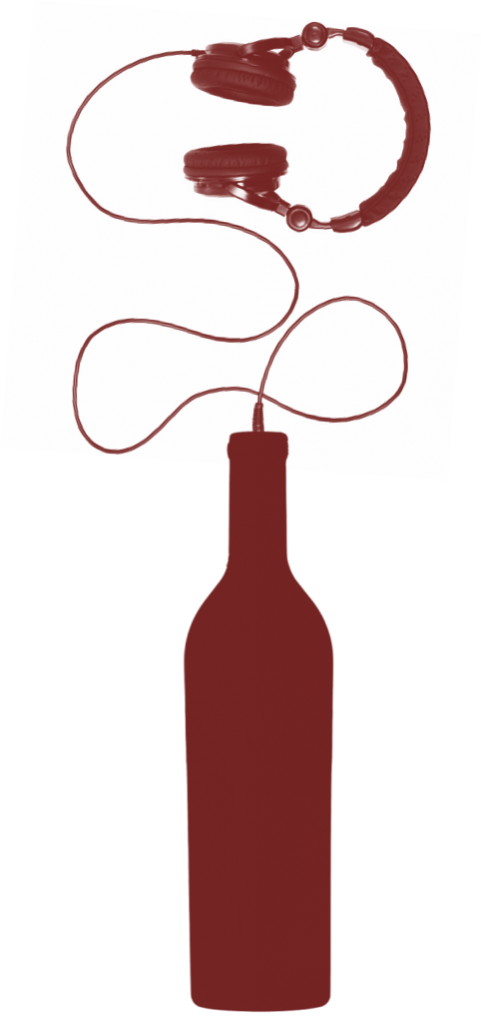

For obvious reasons, American children are not introduced to a ‘canon’ of great wines in school. Instead, we grow up sifting through culture for cues and shorthands to help us decide what to drink. Some men tend to drink red exclusively, fearing that white is feminine. People stay away from Merlot in part because it was disparaged in the movie Sideways, (despite the fact that the protagonist’s most prized possession is a bottle of a Merlot based wine.) Buyers stick to famous place-names like Bordeaux, Chianti and Napa, while avoiding lesser known regions. At the same time, they’ll call just about any sparkling wine ‘Champagne,’ even if it wasn’t grown and made there. In the end, people prefer to buy by varietal, like ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ or ‘Pinot Noir,’ rather than the growing region. Most people wouldn’t be able to point to Bordeaux on a map, and if they haven’t been there, they don’t care about it. But they’ve had a ‘Cab’ before, and know they liked it, and hear good things about it, so what the heck.

What does a winery do when they are not from a famous region? Or making wines from lesser known varietals? How do consumers differentiate one Cab from another? The people who have the most money and time to figure out these questions are large, multi-million dollar wine companies. Additionally, they ask, how can a large mass-producer disguise the fact that there is nothing special about their wine? The answer: to market it kind of like a book– or a gimmick at Spencer’s Gifts. Slap a cool sounding name on it, and an appealing image, and send it to market. People will want to buy it, because the name is a hoot, and its stacked in a pyramid, so it must be a big deal. To be honest, most people don’t have a specific reason for getting a Bordeaux, so why not get the one with the crazy label instead?

In 2000, the bulk-bottled Australian import Yellowtail arrived on American store shelves. It was cheap, and had a stylized Kangaroo on the label. Half cartoon, half Aboriginal sketch, the kangaroo was sophisticated enough for a dinner-party, but ridiculous enough to call attention to itself. Yellowtail did not start the ‘critter label’ fad, but it does exemplify it. Little Penguin, Smoking Loon, Dancing Bull and Gato Negro come to mind, as does Tussock Jumper, where every varietal in the line is symbolized by a different animal wearing a red sweater. Some of the best-known luxury wineries, like Screaming Eagle and Duckhorn and Frogs Leap, preceded this trend, yet profit from and increasingly engage in it.

Critter labels soon drew the ire and exasperation of wine critics, disgusted that so much attention could be drummed up for such mass-produced plonk. The marketing strategy seemed infantile and manipulative: people like animals, and like to purchase things with animals on them. Critter labels are so stupid they’re savvy– they play into our earliest associations with the countries that supply bulk wine, like Australia, South Africa, Spain and Argentina. We may not know much about these countries, but we’ve been watched Bugs Bunny bull-fight from birth, and grew up identifying Australia with kangaroos. France and Italy don’t have signature animals, but they don’t need them either; we associate France with wine, not with roosters. (Yet Le Vielle Ferme displays a prominent rooster on the label, in any case.)

For all that’s been said against critter labels, and for their weird colonial baggage, (Australia= exotic animals!) at least they sort-of, sometimes hint at the provenance of a wine, and insist that this is important information for the consumer. In most industries, this is a laughable anachronism. Who cares where one’s toothpaste or phone come from? Yet with fine wines, the place of origin is the reason it will taste a certain way, and when you smell it, remind you of certain things, and highlight different kinds of memories. The place determines how the wine will be meaningful to you, in and of itself. With bulk wines, not so much. Too many grapes from too many places went into it, and the wine has been stripped of its unique characteristics, so as to ensure shelf life and uniformity. These wines can be good, and are dependable, but not particularly meaningful. Like toothpaste. So its no surprise that the industry has developed another method, where the origin and varietals are incidental, and the brand and concept becomes the only thing that matters. In order for this to work, the brand has to be alluring, a little shocking, and “share-worthy.”

The shamelessly trendy marketing strategy is now the creepy label.

The Prisoner might be the king of creepy labels. It was originally created by Orin Swift, who has a whole line of disturbing labels, featuring knives and dismembered mannequins and jarring Dadaist collages. At Weilands in Columbus, OH, I was pleased to find The Prisoner posed against JC Cellar’s The Impostor– had the store actually sorted them this way? Then I looked around me:

What is this, Halloween? Even labels I wouldn’t have found creepy beforehand begin to seem a little nocturnal, and frightening. Slo Down’s Sexual Chocolate suddenly looks like it had been scrawled by a demented person. Sans Liege’s Groundwork appeared to be straight out of a Brothers Quay animation. Below them sat 19 Crimes, (opportunistically displaying another prisoner on the label,) and the ubiquitous Apothic Red at the bottom of the shelf. Copolla’s Zoetrope recalled a Kara Walker silhouette. Even critter labels like the Coniglio bunny, and Dashe’s monkey, appeared insidious. And look at all those black capsules, lined up together like a row of fascist uniforms.

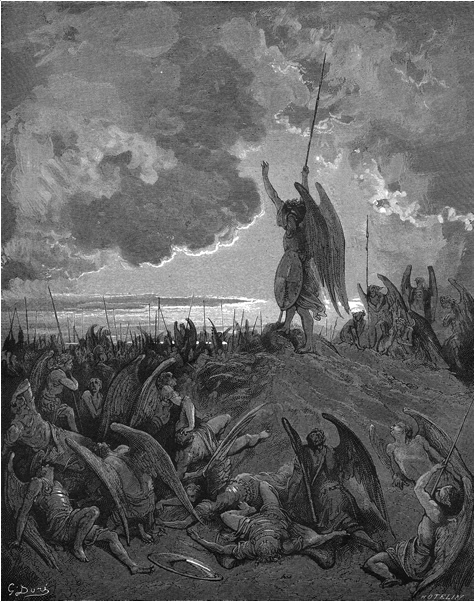

It’s hard not to see parallels in pop culture at large– like the rise in vampire and zombie properties. There’s the Golden Age of Television, which often can be reduced to the Golden Age of Gritty Shows About Conflicted Sociopaths. Turn on the TV, and you’re as likely to find a show about a witch coven or serial killer as a sitcom. ‘Witch house‘ is arguably a musical genre, (or at least a style,) and artists like Future Islands and Tyler, the Creator physically menace their audiences. “Epic battle” style orchestrations straight out of Lord of the Rings grind alongside the hours of run-up footage to the Superbowl, and the entirety of the Olympics. Dimly lit, heavily paneled Speakeasy bars are popping up like daisies. Since the mid to late 2000s, everything must have gravitas, roiling drama, tainted love.

Why not wine too? Its not a far leap of the imagination. In movies, wine is most often drunk by cruel, corrupted villains. More positively, a glass of wine denotes sophistication and mastery– which narratively belong to the bad-guy, not the girl or boy-next-door. Creepy labels play into this understanding.

They also make wine fun. Creepy labels are rebellious, because they are not quite classy. Yet more than anything, they are nostalgic. They are just as accessible as critter labels. What is this flood of dark, gritty imagery, if not an appeal to take the things we loved (and feared) as children seriously? No one ever needs to grow up, because ghost stories and Batman and Harry Potter are for adults. And children’s pajamas. At the same time.

Creepy labels are also a way of making wine a little more guy-friendly. Women drink wine alongside villains. For instance, The Drinks Business recently reported “Men Fear Ridicule Over Ordering Wine” as a headline. Meanwhile, darkness and femininity have been equated for eons. Edgy male characters can appropriate shadowy, ‘feminine’ characteristics while retaining their masculinity. Just like femme fatales, they can seduce, dress well, drink wine, and modulate their voices to be sweet one moment, biting the next, and still remaine masculine. These behaviors are also vaguely aristocratic. While the gap between the rich and poor widens, this is a seductive visage to adopt, even if it is considered less than virtuous.

The safest way for a man to do feminine things is to be diabolical while doing them. Paradoxically, this becomes the most powerful way for a woman to be feminine– to be a woman playing a man playing at being a woman. Rates of wine drinking are rising rapidly amongst young men and women, who in turn re-negotiate what drinking wine ‘means.’ At least with red-blends, the fastest growing category, this re-negotiation confirms Hollywood’s typecasting, while weakening people’s connection to what wine actually is– an expression of a varietal, from a place. How convenient for industrial size producers, who will cloak their wine refineries and tanker trucks with a sexy vampire shroud.

Meanwhile, men and women can be united at last in their choice of blood-red blends with titillating names, leaning aloofly over vintage bars, and decorating the kitchen table with mysterious black bottles. Whoever brings the most sinister wine to the party wins.

———

This piece is an amalgamation of two posts that went up on The Nightly Glass, a wine in culture blog. I’m hoping to make it like The Hooded Utiltiarian equivalent for wine, beer and spirits criticism, and would appreciate it if you check it out!