(Honoring online comics criticism written or published in 2012. A call for nominations and submissions.)

This is part of a semi-annual process to choose the best online comics criticism. The first quarter nominations can be found here.

When I survey the field of comics criticism, it sometimes occurs to me that the popularity of a piece is frequently inversely related to the amount of effort and thought put into writing it. Why then do individuals continue to produce long thoughtful articles? The truth is that they don’t or rather not with the kind of frequency the form actually needs, and especially not when the work is done gratis. But putting these things aside, perhaps it is in the nature of these writers to go to such lengths. We can put some of this serious writing down to a sense of personal endeavor, academic training, and the intense hobbyist with a competitive spirit.

There is also the question of critical communities. If a community favors the latest costume changes, creative team shifts, and the latest news from the big two then news hungry one-upmanship will probably be the norm. If the central idea of a community is to contribute to a critical project centered on comics (social, aesthetic etc.), then the tone of the articles will follow suit. The quality of the articles will be dependent on the taste and discipline of the editor and the commitment of a core team of writers; both these factors engendering a critical climate in which only writing of a certain quality is to be expected of all who contribute. A piece meal promotion of more elevated writing will depend far too much on the individual writer’s proclivities and drive to sustain quality (a central problem with an earlier incarnation of TCJ.com.) This is especially true for comics criticism where amateur sites have a disproportionate influence and editorial influence severely curtailed.

Reiteration: Readers should feel free to submit their nominations in the comments section of this article. Alternatively I can be reached at suattong at gmail dot com. Web editors should feel free to submit work from their own sites. I will screen these recommendations and select those which I feel are the best fit for the list. There will be no automatic inclusions based on these public submissions. Only articles published online for the first time between January 2012 and December 2012 will be considered. I have included some Hooded Utilitarian articles in the selection, mainly from people who I have little to no contact with. Readers (but not contributors) of HU should submit their own nominations for this quarterly process.

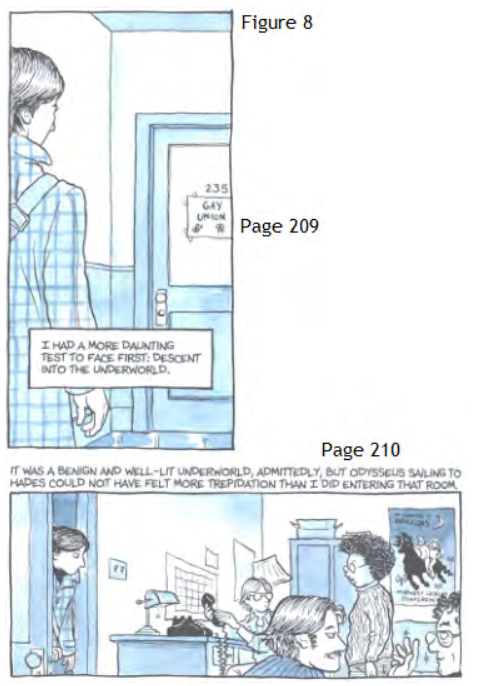

[Matt Seneca burning some pompous rubbish…apparently]

Sarah Boxer on Krazy Kriticism. At one point in her article, Boxer writes:

Now that Krazy Kritics have gotten their dearest wish — all of the SundayKrazys published in book form — what will happen to Kriticism? Will it yield to real criticism?…One essay in Yoe’s collection, Douglas Wolk’s “The Gift,” offers a ray of hope. Wolk finds something new to analyze in the strip — its peculiar pace: “The real comedy of Krazy Kat is almost always slower than its surface humor, which is appropriate for a strip whose central joke is miscommunication on a grand scale. The one way you can’t read it for pleasure is quickly.”

While Boxer offers a nice survey of Krazy Kat criticism, this revelation seems more like stating the obvious than anything novel. Not that stating the obvious isn’t useful but it should be correctly labeled as such. Her more interesting point, I think, is that Krazy Kat lacks development, a claim which I think is not indisputable but worth discussing.

Steven Brower on Kirby’s collages.

Robb Fritz – Moves Like Snoopy. Fritz’s article doesn’t have the beauty of language which I usually associate with nostalgia-tinged pieces and a lot of the interest in it stems from the collection of quotations from various sources. You can certainly see the seams where the research was fitfully stitched in. It didn’t work for me but that doesn’t mean it won’t work for some.

Kelly Gerald on Flannery O’Connor and the Habit of Art. This is actually an excerpt from the afterword to an upcoming collection of cartoons by Flannery O’Connor. I suppose this only goes to show that people put in an effort when they’re in print (and presumably paid for it.)

Lee Konstantinou on Metamaus (“Never Again, Again”)

Bob Levin on Manny and Bill, Willie and Joe.

Farhad Manjoo on Editorial Cartoons. The news that editorial cartoons are “stale, simplistic, and just not funny” is about as fresh as the idea that superhero comics suck. Manjoo’s insights into the inferiority of Matt Wuerker’s (Pulitzer prize winner) cartoons are also not particularly challenging. Furthermore, the suggestion that political cartoons should be excluded from the Pulitzer PR game is somewhat nonsensical. If the Pulitzer committee was seriously interested in offering prizes only to the best works of American literature and journalism in any one year, they would put serious consideration into adopting and liberally using a “No prize this year” category. As it is, they don’t. Nonetheless, I’m putting this here simply because someone outside the comics reading room finally noticed the obvious. It should also be noted that he does offer some other poor alternatives to political cartoons.

Hannah Means-Shannon – Meet the Magus Part 1 (The Birth Caul) Part 2 (Snakes and Ladders). This article is a bit of a departure for Sequart.org, a site which focuses largely (but not exclusively) on medium to long form articles on superhero and mainstream titles.

Evie Nagy on Tarpé Mills & Miss Fury (“Heroine Chic”).

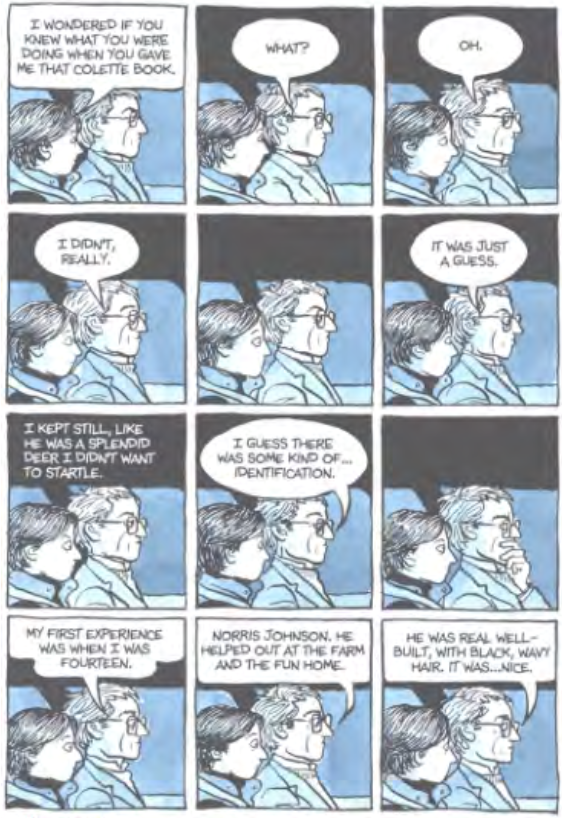

Meghan O’Rourke on Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother?

Katie Roiphe on Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother?

Matt Seneca – Why You Hate Grant Morrison (Life on Earth Q Part 3). This piece was recommended by Noah but, in my opinion, it’s not Seneca doing what he does best. It has a kind of novelty appeal since Seneca hardly ever does negativity but he still needs a few more practice swings to get used to the feel of the hatchet.

Jason Thompson on Shigeru Mizuki. As evidenced by the poll 2 years ago, Thompson’s articles for his House of 1000 Manga column are a big favorite in the manga blogging community.

Kristy Valenti on Astro City and the White Man’s Burden.

Chip Zdarsky – Who Writes the Watchmen? From the first quarter of 2012. Nominated by Jones.

At The Hooded Utilitarian

Eric Berlatsky on Los Bros Hernandez (Parts 1 and 2).

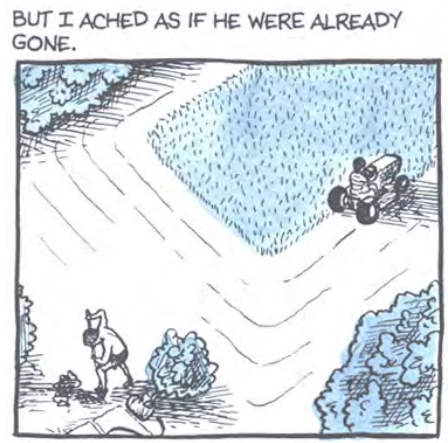

Corey Creekmur – Remembering Locas. This is from the tail end of March but wasn’t included in the previous listing. Nominated by Jeet Heer.

Sharon Marcus – Wonder Woman vs. Wonder Woman

Andrei Molotiu – Built by a Race of Madmen. From the first quarter of 2012. Nominated by Gary Verkeerts.

Katherine Wirick on Watchmen: Heroic Proportions.

At TCJ.com

Prajna Desai on Bhimayana.

Jeet Heer – Crumb in the Beginning

Ryan Holmberg on Tezuka Osamu and The Rectification of Mickey.

Ken Parille – Six Observations about Alison Bechdel’s Graphic Archive Are You My Mother?

Dash Shaw on Jeffrey Brown’s Cat Comics.

Kent Worcester on British Comics: A Cultural History.

The Jack Kirby: Hand of Fire Roundtable (Parts one, two, and three). Organized by Jeet Heer and starring Glen Gold, Sarah Boxer, Robert Fiore, Doug Harvey, Jeet Heer, Jonathan Lethem, and Dan Nadel. I have no doubt that this roundtable will be on many people’s short list of best comics criticism for the 2012. It’s messy, sometimes incoherent, occasionally funny and, towards its close, reasonably informative. Some of the participants are true blue Kirby experts which makes it all the more disappointing they weren’t pushed in the right direction or milked more thoroughly. As James Romberger suggests in the comments of the third section of this roundtable, this should have been extensively edited so as to ensure a sensible flow of ideas (not to mention the excision of ridiculous amounts of noise). Personally, I would have preferred fully worked-out essays as opposed to a mailing list discussion.

I had hoped that TCJ.com would expend its energies on topics and comics which have had 1/100th of the exposure Kirby’s comics but I think that would be asking too much. There has been a consistent devotion to the comics of Kirby in The Comics Journal since its inception and TCJ.com and Jeet et al. merely extend this tradition. The lack of a balancing voice in the exchange is also telling. Sarah Boxer’s dissent (in the third section of this debate) while amusing hardly constitutes a proper reassessment of Kirby’s influence and real worth.