The following lists were submitted in response to the question, “What are the ten comics works you consider your favorites, the best, or the most significant?” All lists have been edited for consistency, clarity, and to fix minor copy errors. Unranked lists are alphabetized by title. In instances where the vote varies somewhat with the Top 115 entry the vote was counted towards, an explanation of how the vote was counted appears below it.

In the case of divided votes, only works fitting the description that received multiple votes on their own received the benefit. For example, in Jessica Abel’s list, she voted for The Post-Superhero comics of David Mazzucchelli. That vote was divided evenly between Asterios Polyp and Paul Auster’s City of Glass because they fit that description and received multiple votes on their own. It was not in any way applied to the The Rubber Blanket Stories because that material did not receive multiple votes from other participants.

Jessica Abel

Cartoonist, La Perdida, Mirror, Window; co-editor, The Best American Comics series; instructor, School of Visual Arts

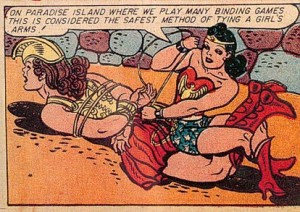

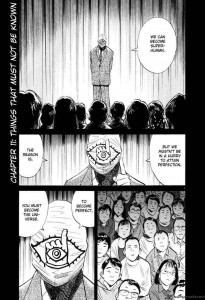

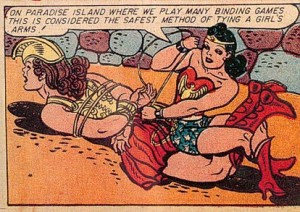

Wonder Woman, William Moulton Marston & Harry G. Peter

- The Collaborations, José Muñoz & Carlos Sampayo

Counted as a vote for The Alack Sinner and Le Bar à Joe [Joe’s Bar] Stories, José Muñoz & Carlos Sampayo

- Fun Home, Alison Bechdel

- The Jimbo Stories, Gary Panter

- The Journalistic Comics, Joe Sacco

Counted as a vote for Palestine, Joe Sacco

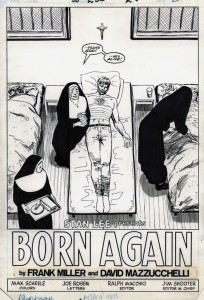

- The Post-Superhero Comics, David Mazzucchelli

Counted as a 0.5 vote each for Asterios Polyp, David Mazzucchelli, and Paul Auster’s City of Glass, Paul Karasik & David Mazzucchelli

- Terry and the Pirates, Milton Caniff

- THB and Related Stories, Paul Pope

- Wonder Woman, William Moulton Marston & Harry G. Peter

- Works, Blutch

- Works, Jaime Hernandez

Counted as a vote for The Locas Stories, Jaime Hernandez

Max Andersson

Cartoonist, Pixy, Death & Candy

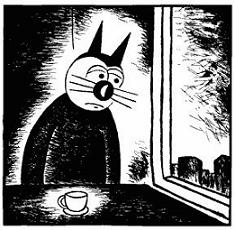

Klas Katt, Gunnar Lundkvist

- Amy and Jordan, Mark Beyer

- Felix, Jan Lööf

- Jack Survives, Jerry Moriarity

- Klas Katt, Gunnar Lundkvist

- Krazy Kat, George Herriman

- Moomin, Tove Jansson

- Nancy, Ernie Bushmiller

- Tekkon Kinkurîto [Black and White], Taiyo Matsumoto

- Thimble Theatre, starring Popeye, E. C. Segar

- Underworld, Kaz

Deb Aoki

Cartoonist, Bento Box; writer, Manga About.com

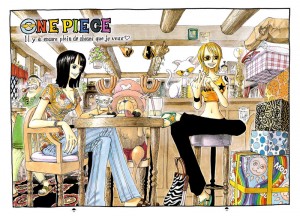

Wan Pîsu [One Piece], Eiichiro Oda

- 1. Akira, Katsuhiro Otomo

- 2. Kozure Ôkami [Lone Wolf and Cub], Kazuo Koike & Goseki Kojima

- 3. Bishôjo Senshi Sêrâ Mûn [Sailor Moon], Naoko Takeuchi

- 4. Ranma ½, Rumiko Takahashi

- 5. Emma, Kaoru Mori

- 6. Love and Rockets, Gilbert Hernandez & Jaime Hernandez

Counted as a 0.5 vote each for The Locas Stories, Jaime Hernandez, and The Palomar Stories, Gilbert Hernandez

- 7. Elfquest, Wendy Pini & Richard Pini

- 8. Vagabond, Takehiko Inoue

- 9. Bone, Jeff Smith

- 10. One Piece, Eiichiro Oda

COMMENTS

1. Akira

Just a tour de force of graphic storytelling. Epic in scope and ambition with breathtaking art, Akira is a uniquely Japanese statement on power, corruption, rebellion, friendship, betrayal, innocence lost, and so much more. It still blows me away every time I read it.

2. Lone Wolf and Cub

A masterwork. If you’ve read Frank Miller’s Daredevil or Rônin, and you haven’t read Lone Wolf and Cub, you are really missing out. Beautiful brushwork, cinematic pacing, gut-wrenching action, heartbreaking, and historically fascinating.

3. Sailor Moon

I grew up reading shôjo manga, so women creating comics was nothing new to me. But for a generation who experienced this shôjo adventure series, being exposed to the Sailor Moon manga (and anime) series was a watershed moment. While the U.S. comics biz thinks “strong female characters” must carry big guns and have even bigger boobs, Naoko Takeuchi showed how a comics creator can inspire and engage female readers without talking down to them.

4. Ranma ½

Frequently mentioned as a “gateway drug” to manga, Ranma ½ was many readers’ first encounter with the kind of wacky, gender-bending fun that manga has to offer. This light-hearted romantic comedy is a rare comics series that appeals to both male and female readers—it’s little wonder that Rumiko Takahashi is so popular. She may be a bit repetitive, but when she finds a formula that works, it works really well.

5. Emma

So elegantly drawn, so beautifully told. Kaoru Mori does so much with facial expressions and how she develops her characters. The short stories in volumes 8 and 9 illustrate how well she created her world and the richly realized characters who live in it. Her painstaking attention to historical accuracy never weighs down the story—she immerses the reader in a fully realized world, and shows the changes that occurred in England from the late 1800s to the early 1900s through the lives of the people, not just dry facts. If I ever want a pick-me-up, I read Emma, Volume 10—the most satisfying ending to a manga or comics series I have read.

6. Love and Rockets

At a time when I was reading X-Men and Daredevil, Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez showed me that comics could be about other stuff I cared about—like punk rock—and worlds I never knew, like life as a Latino in southern California. It made me realize I could draw comics about my experiences as a Japanese-American gal growing up in Hawaii, balancing my punk-rock and art-school life with my family traditions.

7. Elfquest

When I first encountered Elfquest, I was in the sixth grade. It’s hard to appreciate how revolutionary and different it was when it came out: a black-and-white comic by a female creator, high fantasy, and not from one of the Big Two (Marvel and DC). I love the original story-arcs of this series because they were so well thought-out, and infused with so much love for the characters and their readers.

8. Vagabond

Again, a beautifully drawn series. Takehiko Inoue really captures what it’s like to swing a sword knowing that you could cut off someone’s arm, or be sliced or stabbed in return. As you read this story, you really feel the weight of the sword, the feeling of flesh being cleaved, the blood, the fear of dying, and the exhilaration of battle. Breathtaking art, with a smartly told story about a young man who discovers that true strength comes from the spirit, not solely from his sword.

9. Bone

Ask anyone to recommend a comics series to a friend who doesn’t usually read comics, or to a kid. Nine out of 10 times, people will recommend Bone. For good reason! It’s action-packed, funny, wonderfully drawn, and terrifically well told. This deserves to be in print forever.

10. One Piece

Every time I read One Piece, I’m just astounded at Eiichiro Oda’s inventive character designs, his infectious enthusiasm, and the heart and humor with which he infuses the story. The rest of the world is completely in love with this series—it’s one of the highest-selling in Japan today, selling millions of copies each time a new volume comes out, and breaking sales records every time. It definitely deserves more props in the U.S.

Bonus:

11. Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns

I know this one will be picked by almost everyone you ask, but I can’t exclude it from my list! I sometimes blame this whole “make all superheroes dark and gritty” trend on Frank Miller. But when it came out, it was shocking, astonishing, and punch-in-the-gut bats**t crazy (no pun intended). (O.K., maybe it was intended. Never mind.) I remember where I was when I first read it—how many comic books can you say that about?

Michael Arthur

Cartoonist, Funny Animal Books; contributing writer, The Hooded Utilitarian

Klezmer, Joann Sfar

- L’Ascension du haut-mal [Epileptic], David B.

- Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson

- Cardcaptor Sakura, CLAMP

- Concrete, Paul Chadwick

- The Great Catsby, Doha

- Klezmer, Joann Sfar

- Love and Rockets, Gilbert Hernandez & Jaime Hernandez

Counted as a 0.5 vote each for The Locas Stories, Jaime Hernandez, and The Palomar Stories, Gilbert Hernandez

- Moomin, Tove Jansson

- Usagi Yojimbo, Stan Sakai

- Varulvene i Montpellier [Werewolves of Montpellier], Jason

Nate Atkinson

Assistant Professor of Communication, Georgia State University

Doom Patrol, Grant Morrison & Richard Case

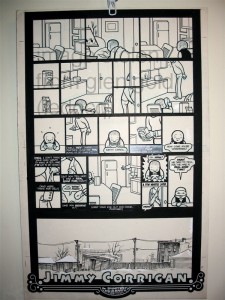

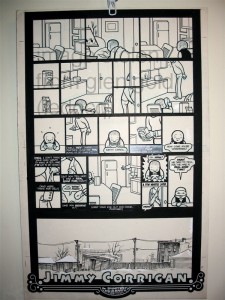

- The ACME Novelty Library, Chris Ware

Counted as a 0.25 vote each for “Building Stories,” Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, Quimby the Mouse, and Rusty Brown, including “Lint”.

- Akira, Katsuhiro Otomo

- The Doom Patrol stories, Grant Morrison & Richard Case, with Scott Hanna, et al.

- The Fate of the Artist, Eddie Campbell

- Le Garage hermétique [The Airtight Garage], Jean “Moebius” Giraud

- The Jimbo stories, Gary Panter

- The Kin-der-Kids, Lyonel Feininger

- “Love’s Savage Fury,” Mark Newgarden

- Six Hundred and Seventy-Six Apparitions of Killoffer, Patrice Killoffer

- “The Trumpets They Play!”, Al Columbia

Derik Badman

Cartoonist, Things Change and Maroon; writer, MadInkBeard; contributing writer, The Panelists, The Hooded Utilitarian

King Cat Comics and Stories, John Porcellino

- The End, Anders Nilsen

- Fifty Days at Iliam, Cy Twombly

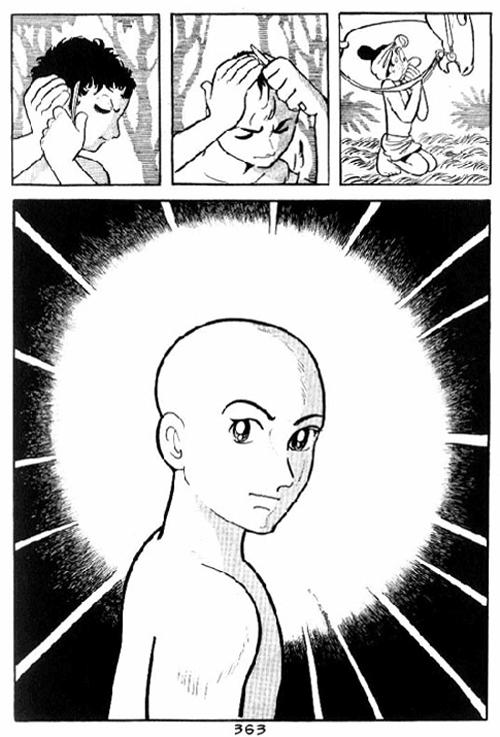

- Hi no Tori [Phoenix], Osamu Tezuka

- How to Be Everywhere, Warren Craghead

- Journal (3), Fabrice Neaud

- King-Cat Comics and Stories, John Porcellino

- Krazy Kat, George Herriman

- The Locas Stories, Jaime Hernandez

- Par les sillons [By the Furrows], Vincent Fortemps

- Peanuts, Charles M. Schulz

J. T. Barbarese

Associate Professor of English, Rutgers University

Pogo, Walt Kelly

- Classic Comics: Frankenstein, art by Robert Webb & Ann Brewster, & Classics Illustrated: Treasure Island, art by Alex Blum

- The Cold War Political Cartoons, Herblock

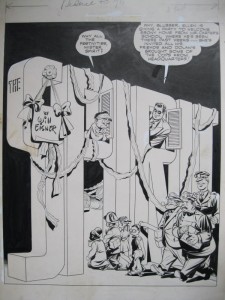

- A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories, Will Eisner

- The MAD Stories, Will Elder

Counted as a vote for MAD #1-28, Harvey Kurtzman & Will Elder, Wallace Wood, Jack Davis, et al.

- The New Yorker Cartoons, Roz Chast

- Peanuts, Charles M. Schulz

- Pogo, Walt Kelly

- The Sandman (especially Season of Mists), Neil Gaiman, et al.

- Watchmen, Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons

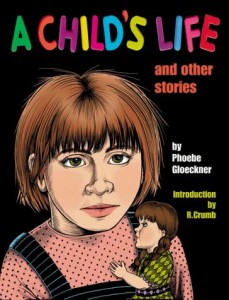

- The Zap Comix Stories, R. Crumb

Counted as a vote for The Counterculture-Era Stories, R. Crumb

COMMENTS

Bill Elder’s work in the Fifties and early Sixties for MAD magazine, particularly the film and comic strip parodies (of Archie comics, especially).

Roz Chast, anything she does or has done for The New Yorker. Pure genius.

R. Crumb’s Zap stuff, and his creation of the single most memorable alternative-comix character, Mr. Natural.

Whoever did the art for the original Classics Comics version of Treasure Island and Frankenstein

Will Eisner’s A Contract with God.

Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman (especially Season of Mists).

Watchmen.

Charles M. Schulz, who along with Jules Feiffer essentially defines sophisticated mid-20th-century American irony.

Herblock’s Cold War political cartoons (viz., his sequence on the Cuban Missile Crisis).

Walt Kelly’s Pogo.

And if illustrators were allowed: Boris Artzybasheff’s work on Charles G. Finney’s The Circus of Dr. Lao, and Joe Mugnani’s amazing drawings for Ray Bradbury’s October Country.

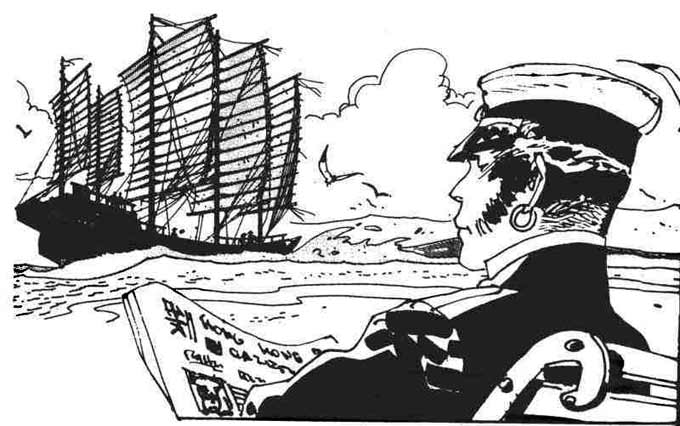

Edmond Baudoin

Cartoonist, Le voyage and Le chemin de Saint-Jean

Corto Maltese, Hugo Pratt

Jonathan Baylis

Cartoonist, So… Buttons

Preacher, Garth Ennis & Steve Dillon

- The ACME Novelty Library, Chris Ware

Counted as a 0.25 vote each for “Building Stories”, Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, Quimby the Mouse, and Rusty Brown, including “Lint”.

- American Splendor, Harvey Pekar, et al.

- Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, Frank Miller, with Klaus Janson & Lynn Varley

- The Fantastic Four Stories, John Byrne

- Grendel, Matt Wagner, et al.

- Kozure Ôkami [Lone Wolf and Cub], Kazuo Koike & Goseki Kojima

- Metropol, Ted McKeever

- Preacher, Garth Ennis & Steve Dillon

- The Swamp Thing Stories, Alan Moore & Stephen R. Bissette, John Totleben, Rick Veitch, et al.

- Yummy Fur, Chester Brown

Counted as a 0.33 vote each for Ed the Happy Clown, I Never Liked You, and The Playboy.

COMMENTS

Faves, not Best, right?

Child/Teen in Me

1. Batman: The Dark Knight Returns – Frank Miller – something about the combination of the crazy collector’s market at the time, HOT books and all that, with a story I actually loved at the time. What was I, 13?

2. Fantastic Four – John Byrne (particularly #245 – “Childhood’s End”) – something about Byrne’s FF run made me a fan for most of my life. I actually own the original art of the page where Franklin causes H.E.R.B.I.E’s destruction.

3. Lone Wolf and Cub – Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima – Liked the Frank Miller covers on these books when they were published by First, but loved the stories inside. So glad Dark Horse collected the entire series years later. So worth the wait.

4. Swamp Thing – Alan Moore, Steve Bissette & John Totleben – My one summer at a sleepaway camp, my grandmother bought me a bunch of comic books. Like a dozen Archies, and an Alan Moore Swamp Thing. I threw out the Archies.

Adult in Me

5. American Splendor – Harvey Pekar – Easily my biggest inspiration for doing my own auto-bio comics, even though I read Chester Brown, Seth, and Joe Matt first.

6. Grendel – Matt Wagner & Others (entire Comico run) During Web 1.0, I sought out this entire series and then read the whole thing in one fell swoop. One of the more ambitious projects of its kind that I’ve ever read.

7. ACME Novelty Library – Chris Ware – Somehow, I lucked out and actually caught this at Issue #1. Brilliant from the first page. I remember the hilarious moments, like those fake ads, more than the depressing Corrigan ones people always seem to refer to.

8. Metropol – Ted McKeever – Found these in London when I did a semester abroad at a comic shop owned by an ex-pat from Brooklyn! Something about it just hit me the right way. No one is like McKeever.

9. Preacher – Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon – Easily Ennis’s best work. It strikes so many chords with me with its combination of macabre humor and romance.

10. Yummy Fur – Chester Brown (entire run, not just storylines turned into graphic novels) – These simply knocked me on my ass.To go from the surreal and fantastic Ed the Happy Clown to the most frank, revealing auto-bio comics of its time. Amazing.

Books I wish I could’ve included somehow: Asterios Polyp, Beanworld, Bone, Blueberry, Concrete, Daredevil: Born Again, Donjon [Dungeon], Maus, Miracleman, Moonshadow, My New York Diary, The Sandman, Strangers in Paradise.

Melinda Beasi

Writer, Manga Bookshelf

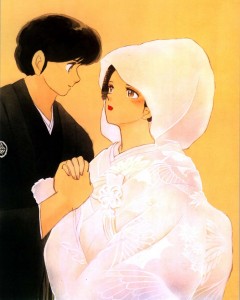

Maison Ikkoku, Rumiko Takahashi

- Banana Fish, Akimi Yoshida

- Boku no Chikyû o Mamotte [Please Save My Earth], Saki Hiwatari

- Flower of Life, Fumi Yoshinaga

- Hagane no Renkinjutsushi [Fullmetal Alchemist], Hiromu Arakawa

- Hikaru no Go, Yumi Hotta & Takeshi Obata

- Kirihito Sanka [Ode to Kirihito], Osamu Tezuka

- Maison Ikkoku, Rumiko Takahashi

- Paradise Kiss, Ai Yazawa

- Tôkyô Babylon, CLAMP

- Wild Adapter, Kazuya Minekura

COMMENTS

A fairly arbitrary list of ten of my favorite comics, subject to change at any particular moment, and in no particular order.

With one major exception, I restricted this list to completed series (or, at least, completed in Japan, and very nearly completed here).

Terry Beatty

Co-creator & artist, Ms. Tree; inker, The Batman Adventures

Terry and the Pirates, Milton Caniff

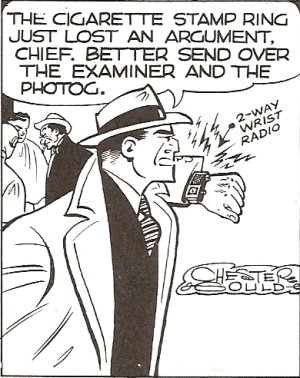

- Dick Tracy, Chester Gould

- The Fantastic Four, Stan Lee & Jack Kirby, with Joe Sinnott, et al.

- Kozure Ôkami [Lone Wolf and Cub], Kazuo Koike & Goseki Kojima

- Li’l Abner, Al Capp

- MAD #1-28, Harvey Kurtzman & Will Elder, Wallace Wood, Jack Davis, et al.

- Prince Valiant, Hal Foster

- Spider-Man, Stan Lee & Steve Ditko

- Terry and the Pirates, Milton Caniff

- Thimble Theatre, starring Popeye, E.C. Segar

- Tintin, Hergé

Robert Beerbohm

Comics historian, BLBComics.com; pioneering comic-book retailer

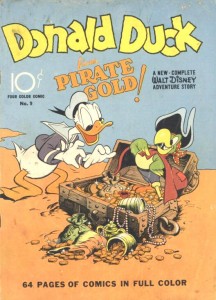

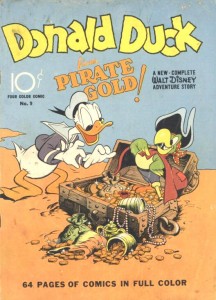

Donald Duck, Carl Barks

- Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson

- The Four-Color one-shots featuring Donald Duck, Carl Barks

Counted as a vote for The Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge Stories, Carl Barks

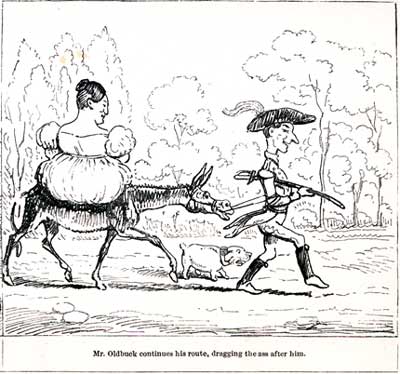

- Histoire de M. Vieux Bois [The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck], Rodolphe Töpffer

Counted as a vote for Works, Rodolphe Töpffer

- Pogo, Walt Kelly

- Polly and Her Pals, Cliff Sterrett (mainly between 1927-1934; after that he used helper ghosts)

- Powerhouse Pepper, Basil Wolverton

- Prince Valiant, Hal Foster

- The Single-Panel Animal Cartoons, T. S. Sullivant

- Spider-Man, Stan Lee & Steve Ditko

- The Spirit, Will Eisner

Piet Beerends

Cartoonist, Idiosyncs and Light Bulb Face

Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson

COMMENTS

I think this would have worked better with a separate list for comic strips and single-panel comics (à la The New Yorker and political cartoons).

Calvin and Hobbes is my favorite by a wide margin, even though it hasn’t influenced my own work at all. Such a fantastic strip. Watterson is an amazing talent, and quit before the strip ever showed any signs of weakness, or a lack of new ideas. He went out on a high note, and never, ever sold out.

Alice Bentley

Office manager, Studio Foglio

Furûtsu Basaketto, Natsuki Takaya

- Beanworld, Larry Marder

- Bone, Jeff Smith

- Digger, Ursula Vernon

- Furûtsu Basaketto [Fruits Basket], Natsuki Takaya

- Girl Genius, Phil Foglio & Kaja Foglio

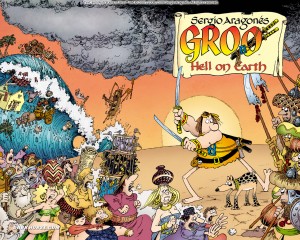

- Groo the Wanderer, Sergio Aragonés, with Mark Evanier, Tom Luth, and Stan Sakai

- Pogo, Walt Kelly

- The Sandman, Neil Gaiman, et al.

- Strangers in Paradise, Terry Moore

- Usagi Yojimbo, Stan Sakai

COMMENTS

Thank you for putting this project together!

[About the vote for Girl Genius] It’s not just loyalty to my employers that prompts me to list this—I really feel they are doing some groundbreaking work.

Eric Berlatsky

Associate Professor of English, Florida Atlantic University; author, The Real, the True, and the Told: Postmodern Historical Narrative and the Ethics of Representation

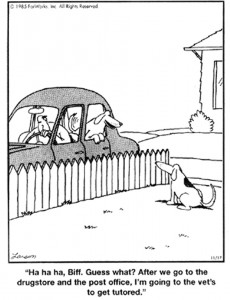

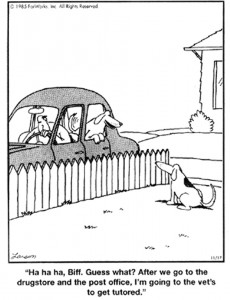

The Far Side, Gary Larson

- 1. Peanuts, Charles M. Schulz (especially 1955-1965)

- 2. Watchmen, Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons

- 3. The Locas Stories, Jaime Hernandez

- 4. The MAD Cartoons, Don Martin

- 5. Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson

- 6. The Far Side, Gary Larson

- 7. The Animal Man Stories, Grant Morrison & Chas Truog, with Doug Hazlewood, et al.

- 8. The Fate of the Artist, Eddie Campbell

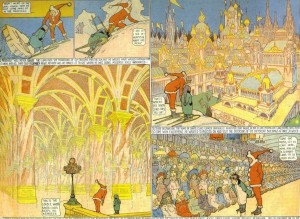

- 9. Little Nemo in Slumberland, Winsor McCay

- 10. The Ambush Bug Stories, Keith Giffen & Robert Loren Fleming

COMMENTS

[About the vote for the Locas stories] If I had to choose one “graphic novel,” I’d probably go with Wigwam Bam. Ghost of Hoppers is also really good!

[About the vote for the Ambush Bug stories] The DC Comics Presents and Action Comics guest appearances, the Ambush Bug mini-series, the Son of Ambush Bug mini-series, the Nothing Special, and the Stocking Stuffer. Not the recent mediocre revival.

Noah Berlatsky

Publisher, The Hooded Utilitarian; contributing writer, the Chicago Reader, Comixology, Splice

Daruma [Not Know], Jiun Onkô

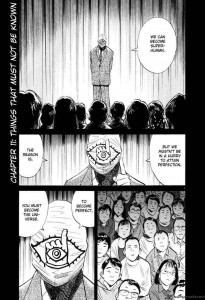

- Daruma [Not Know], Jiun Onkô

- “Hanshin [Hanshin: Half-God]”, Moto Hagio

Counted as a vote for A Drunken Dream and Other Stories, Moto Hagio

- Likewise, Ariel Schrag

- Little Nemo in Slumberland, Winsor McCay

- Manga [The Sketches], Katsushika Hokusai

- Oscar Wilde’s Salomé, Aubrey Beardsley

- Peanuts, Charles M. Schulz

- “Second Chance for a Deadman,” featuring Batman and Deadman, Bob Haney & Jim Aparo

- Watchmen, Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons

- Wonder Woman, William Moulton Marston & Harry G. Peter

COMMENTS

Since I am hosting this, I gratuitously insist on having it noted that the last two I cut off my list were Art Young’s Inferno and Marley’s Dokebi Bride.

Sean Bieri

Cartoonist, Jape; design director and illustrator, Detroit MetroTimes

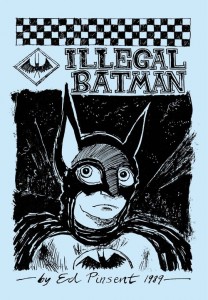

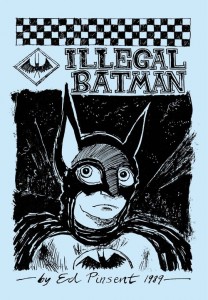

Illegal Batman, Ed Pinsent

- Asterios Polyp, David Mazzucchelli

- “Bimbos from Hell,” Krystine Kryttre

- Fun Home, Alison Bechdel

- Hortus Sanitatis, Frédéric Coché

- “Hypothetical Quandary,” Harvey Pekar & R. Crumb

Counted as a vote for American Splendor, Harvey Pekar, with R. Crumb, et al.

- Illegal Batman, Ed Pinsent

- Kaze no Tani no Naushika [Nausicäa of the Valley of the Wind], Hayao Miyazaki

- Kliban in a Box, B. Kliban

Counted as a vote for Works, B. Kliban

- Tumbleweeds, T.K. Ryan

- Vent litt… [Hey, Wait], Jason

Corey Blake

Writer, www.coreyblake.com

Bone, Jeff Smith

- Asterios Polyp, David Mazzucchelli

- Bone, Jeff Smith

- Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson

- Hark! A Vagrant, Kate Beaton

- Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, Art Spiegelman

- Peanuts, Charles M. Schulz

- Persepolis, Marjane Satrapi

- Scott Pilgrim, Bryan Lee O’Malley

- Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud

- The Walking Dead, Robert Kirkman & Tony Moore and Charles Adlard

“Bobsy Mindless”

Contributing writer, The Mindless Ones

Flex Mentallo, Grant Morrison & Frank Quitely

- L’Ascension du haut-mal [Epileptic], David B.

- Cerebus (the Church and State, Jaka’s Story, and Melmoth volumes), Dave Sim & Gerhard

- Flex Mentallo, Grant Morrison & Frank Quitely

- The Invisibles, Grant Morrison & Steve Yeowell, Phil Jiminez, et al.

- Maniac 5, Mark Millar & Steve Yeowell

- Marshal Law, Pat Mills & Kevin O’Neill

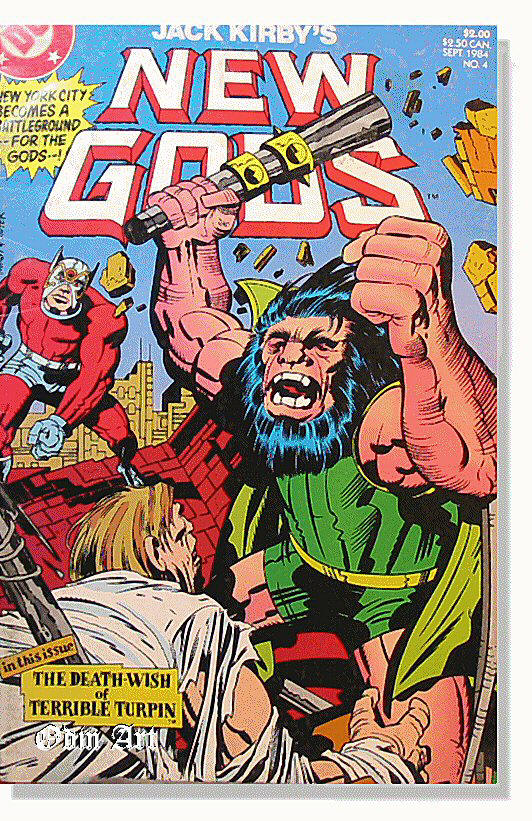

- The New Gods, Jack Kirby, with Mike Royer, et al.

Counted as a vote for The Fourth World Stories, Jack Kirby, with Mike Royer, et al.

- Promethea, Alan Moore & J. H. Williams III, with Mick Gray, et al.

- The Punisher MAX, Garth Ennis, et al.

- Rogan Gosh, Peter Milligan & Brendan McCarthy

Kristin Bomba

Contributing writer, Comicattack.net

Nijusseiki Shônen [20th Century Boys], Naoki Urasawa

- Ayako, Osamu Tezuka

- Bone, Jeff Smith

- 52, Geoff Johns, Grant Morrison, Greg Rucka, Mark Waid, et al.

- Furûtsu Basaketto [Fruits Basket], Natsuki Takaya

- Lex Luthor: Man of Steel, Brian Azzarello & Lee Bermejo

- Nijusseiki Shônen [20th Century Boys], Naoki Urasawa

- Ôoku [Ôoku: The Inner Chambers], Fumi Yoshinaga

- The Sandman, Neil Gaiman, et al.

- Sukippu Bitô! [Skip Beat!], Yoshiki Nakamura

- Y: The Last Man, Brian K. Vaughan & Pia Guerra, with José Marzán, Jr., et al.

COMMENTS

Bone, by Jeff Smith. No other comic I’ve seen can hit such a wide range of readers, in terms of age, sex, or genre preference. Nearly everyone who has seen it loves it. It sells like crack. It’s fantastically drawn, well written, and a truly great read.

Fruits Basket, by Natsuki Takaya. It wasn’t my very first manga, but it was the title that turned me into a serious manga reader.

Lex Luthor: Man of Steel, by Brian Azzarello and illustrated by Lee Bermejo. This brilliant mini-series paints Luthor in a sympathetic light, detailing why he despises Superman so thoroughly.

Ôoku: The Inner Chambers, by Fumi Yoshinaga. It’s hard for me to pick one of Yoshinaga’s works, but I would feel remiss for not including any of them. Ôoku, with its beautifully simple style (yet incredible amount of detail), historical setting, rewrite of history, and intriguing view of feminism make it an absolute must-read for anyone.

Ayako, by Osamu Tezuka. Again, it’s hard to pick one Tezuka work, but I have a special interest in stories about outside influences on traditional cultures, so this one really clicks with me.

20th Century Boys, by Naoki Urasawa. Because it’s brilliant.

52 by Geoff Johns, Grant Morrison, Greg Rucka, and Mark Waid (with layouts by Keith Giffen), from DC Comics. An amazing undertaking, publishing a comic every week. But they pulled it off, and kept the quality consistently high from issue to issue.

Y: The Last Man, by Brian K. Vaughan and Pia Guerra. One of my first real forays into comic books was this brilliant story about the literal last man on Earth.

The Sandman, by Neil Gaiman (and various artists). Fantastic, and perfect for a literature and mythology junkie like myself.

Skip Beat!, by Yoshiki Nakamura. I just adore it so much, I can’t get enough!

Alex Boney

Writer, The Panelists, Back Issue!, and Guttergeek

Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, Chris Ware

- 1. The Question, Denny O’Neil & Denys Cowan

- 2. The Invisibles, Grant Morrison & Steve Yeowell, Phil Jiminez, et al.

- 3. The Sandman, Neil Gaiman, et al.

- 4. From Hell, Alan Moore & Eddie Campbell

- 5. Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, Chris Ware

- 6. All-Star Superman, Grant Morrison & Frank Quitely

- 7. Fun Home, Alison Bechdel

- 8. Watchmen, Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons

- 9. The Spirit, Will Eisner

- 10. Peanuts, Charles M. Schulz

__________

Best Comics Poll Lists

Best Comics Poll Index

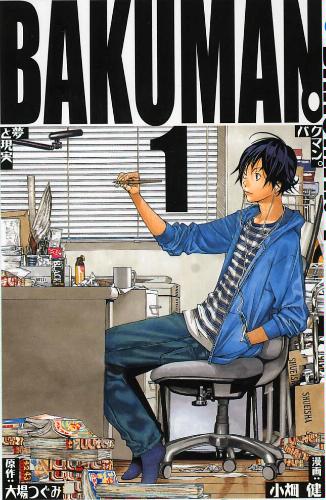

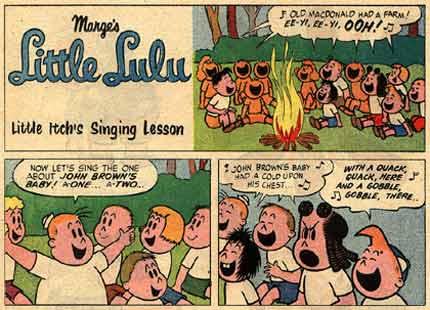

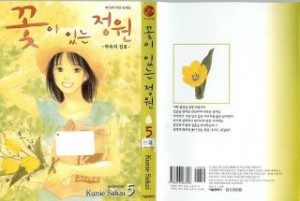

Though manga has been a fixture of the American comics scene since the mid-1980s, it wasn’t until the anime boom of the following decade that publishers began to get savvier about what they were licensing and how they were packaging it. The shift away from manly-man titles towards teen-friendly material, and from floppy to trade paperback, had a big impact on who bought manga; once found only in comic book stores, manga now appeared in big chains like Borders and Walmart where young fans of the Dragonball and Sailor Moon TV shows could find it. By the mid-2000s, manga sales were robust enough to crack the USA Today bestseller list, inspiring more companies to jump into the licensing game.

Though manga has been a fixture of the American comics scene since the mid-1980s, it wasn’t until the anime boom of the following decade that publishers began to get savvier about what they were licensing and how they were packaging it. The shift away from manly-man titles towards teen-friendly material, and from floppy to trade paperback, had a big impact on who bought manga; once found only in comic book stores, manga now appeared in big chains like Borders and Walmart where young fans of the Dragonball and Sailor Moon TV shows could find it. By the mid-2000s, manga sales were robust enough to crack the USA Today bestseller list, inspiring more companies to jump into the licensing game. But perhaps the most striking thing about the top vote-getters is how many of their creators embody the Great Man stereotype. Consider Osamu Tezuka, whose Buddha and Phoenix both made the cut. His role in the history of manga is analogous to Beethoven’s in orchestral music. No musicologist would reasonably claim Beethoven to be the first person to write symphonies, or even the first great innovator within the genre, but Beethoven’s distinctive compositional approach — particularly towards motivic development — had a profound impact on the musicians who came after him. Likewise, Tezuka didn’t invent shojo manga — as some critics have claimed — nor was the he the first person to pioneer the use of “cinematic” layouts. But the popularity and artistry of Tezuka’s work, and the uniqueness of his vision, cemented his reputation as one of the medium’s most important creators, someone who cast the same, anxiety-producing shadow over his successors that Beethoven did over his. (Small wonder that Tezuka’s last project was the bio-comic Ludwig B.)

But perhaps the most striking thing about the top vote-getters is how many of their creators embody the Great Man stereotype. Consider Osamu Tezuka, whose Buddha and Phoenix both made the cut. His role in the history of manga is analogous to Beethoven’s in orchestral music. No musicologist would reasonably claim Beethoven to be the first person to write symphonies, or even the first great innovator within the genre, but Beethoven’s distinctive compositional approach — particularly towards motivic development — had a profound impact on the musicians who came after him. Likewise, Tezuka didn’t invent shojo manga — as some critics have claimed — nor was the he the first person to pioneer the use of “cinematic” layouts. But the popularity and artistry of Tezuka’s work, and the uniqueness of his vision, cemented his reputation as one of the medium’s most important creators, someone who cast the same, anxiety-producing shadow over his successors that Beethoven did over his. (Small wonder that Tezuka’s last project was the bio-comic Ludwig B.)