Art by Rube Goldberg

As you raise spoon of soup (A) to your mouth it pulls string (B), thereby jerking ladle (C) which throws cracker (D) past parrot (E). Parrot jumps after cracker and perch (F) tilts, upsetting seeds (G) into pail (H). Extra weight in pail pulls cord (I), which opens and lights automatic cigar lighter (J), setting off sky-rocket (K) which causes sickle (L) to cut string (M) and allow pendulum with attached napkin to swing back and forth thereby wiping off your chin. After the meal, substitute a harmonica for the napkin and you’ll be able to entertain the guests with a little music.

“Fred’s neighbor buys a jeep, so of course Fred buys a Hummer. I zap him with ‘Keeping up with the Joneses, eh, Freddy?’ He was steamed up, but he doesn’t scare me. The palooka may be built like a goon, but he’s more Caspar Milquetoast than Superman.“

The ocean of the English language is fed by many rivers, and some of the main streams are those of popular media.

Movies, television, songs, theater, vaudeville, books, radio… all have created uncounted idioms, words, catch-phrases and phatic utterances.

Cartoons and comics have contributed their own rich share:

The comic-strip artist[…]has been a very diligent maker of terse and dramatic words.

–H.L. Mencken, The American Language

In this column we’ll review a sampling of these colorful idioms.

Part one of the five-part series focusses on American English from the early newspaper comic strips and cartoons.

Along the way, however, we’ll debunk some false etymology. And because, at times, cartoons have influenced a word’s meaning without creating the word itself, we’ll also take note of such ambiguous cases. Most examples were invented by me, but if attributed they’re actual quotations.

We’ll kick off with a look at a man who was one of the most famous cartoonists of his day; although his life and work are now obscure, his coinages live on in the vernacular: Thomas Aloycious Dorgan (1877 – 1929), who signed his work Tad.

click image to enlarge

W. J. Funk, of the Funk and Wagnall’s dictionary company, placed Dorgan at the top of the list of the ten “most fecund makers of American slang.”

Tad is generally credited with either creating or popularizing such words and expressions as dumbbell (a stupid person; see cartoon above); for crying out loud (a cry of exasperation); cat’s meow and cat’s pajamas (as superlatives); applesauce (nonsense); cheaters (eyeglasses); skimmer (a boater hat); hard-boiled ( for a tough person); drugstore cowboy (loafers or ladies’ men); nickel-nurser (a miser); as busy as a one-armed paperhanger (overworked); Yes, we have no bananas, which became a popular song, still heard today; Twenty-three, Skidoo, (let’s get out of here); and dogs for shoes.

However, he is best-remembered today for coining the word “hot dog” for the frankfurter sandwich that appeared at the turn of the century.

Nathan’s of Coney Island, birthplace of the hot dog. The establishment is still there, and the nosh is still great.

Alas! This appears to be a case of faux folk etymology.

Supposedly, Tad had drawn a cartoon of a dachsund between two buns and christened it the Hot Dog– as in this modern re-creation:

However, no trace of this cartoon has ever been found in Tad’s works. The term probably came from common jokes about dog meat being inserted into cheap sausages.

This term for a sausage served on a bun got its start in college slang in the 1890s. The first known (printed) use of the term is in the Knoxville Journal (Tennessee) on 28 September 1893:

“It was so cool last night that the appearance of overcoats was common…Even the weinerwurst men began preparing to get the “hot dogs” ready for sale Saturday night.“

From the Yale Record of 19 Oct 1895:

“They contentedly munched hot dogs during the whole service.“

Two weeks earlier, on 5 October, that same paper recorded a poem, “Echoes From The Lunch Wagon”:

“‘Tis dogs’ delight to bark and bite

Thus does the adage run.

But I delight to bite the dog

When placed inside the bun.”

No Tad in sight in hot-dog land… but he was still a mighty coiner of words!

*******************************************************

We are on firmer ground tracing how a cartoon led to the naming of a much-beloved toy:

President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt was an ardent big-game hunter. One day in Mississipi, the game was scarce. Some of Roosevelt’s aides captured an old she-bear and tied it to a tree for the President to shoot. Roosevelt, disgusted by this lack of sportsmanship, refused.

The cartoonist Clifford Berryman was inspired by this anecdote to draw in 1902 the above cartoon, “drawing the line in Mississipi”. It was immensely successful and was copied the nation over.

Berryman began inserting a bear into any cartoon featuring Roosevelt, but changing it from an adult to a cub:

A shopkeeper, Morris Michtom, took two stuffed bear dolls made by his wife and put them in his shop window.

Michtom asked for permission from President Roosevelt to call them “Teddy’s bears”. ( His store eventually became the Ideal Novelty and Toy Company.) And thus was born the teddy bear.

That’s just one example of cartoon to toy to language.

************************************************************

“With her apple cheeks and sweet smile she’s as cute as a kewpie doll.”

The Kewpies (derived from ‘Cupid’) were the angelic babies featured from 1909 in the magazine Ladies’ Home Journal, the creation of cartoonist and illustrator Rose O’Neill (1874– 1954):

In 1912 O’Neill licensed production of dolls based on her characters, thus creating one of the most successful toys in history.

Rose O’Neill surrounded by Kewpie dolls

A ‘kewpie doll’ look referred to women who were pretty in a chubby, childlike way; it wasn’t always a compliment. (Animated cartoon star Betty Boop owed a lot of her design to the kewpies.)

At carnival fairgrounds, kewpie dolls were frequent prizes at shooting galleries and other games. Hence the sarcastic expression ‘You win the kewpie doll’ when someone guesses an answer correctly.

**********************************************************

“Jim’s neighbor has a tennis court, so of course Jim has to install a swimming pool — he’s just keeping up with the Joneses.”

This popular expression denoting envy- motivated consumption comes from the title of Arthur R. “Pop” Morand‘s strip chronicling the life of the McGinis family. These upwardly mobile middle-class denizens occasionally referred to their neighbours, the Jones family, with envy or anxiety in their constant war to one-up them:

Interestingly, the Joneses never appeared in the strip named for them.

****************************************************************

“The staples of old yellow journalism are the staples of the new yellow journalism: sex, crime; and, even better, sex crime.” —Nick Denton, Gawker founder

In the 1890’s, there was a fierce commercial war between two popular New York papers: Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World and William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal. They competed with sensationalist stories, eye-catching illustrations, and an innovation that was to spread to every newspaper in the land: the Sunday color comic-strip supplement.

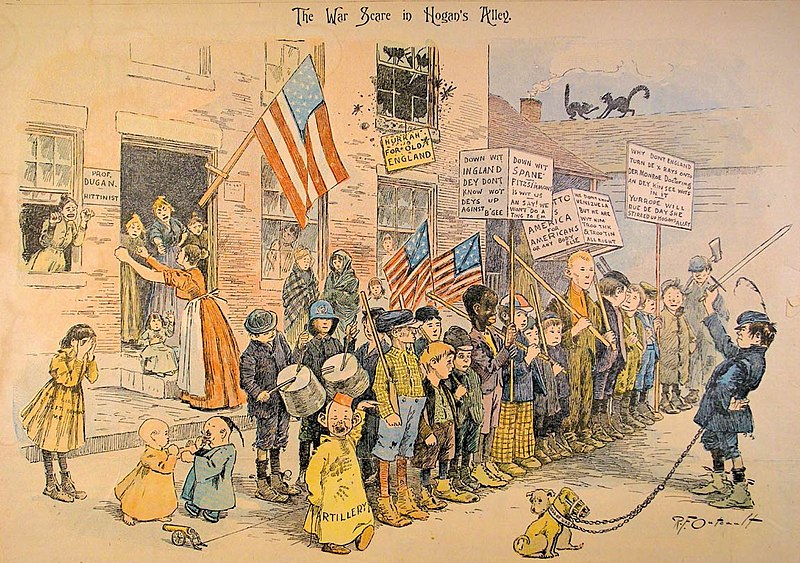

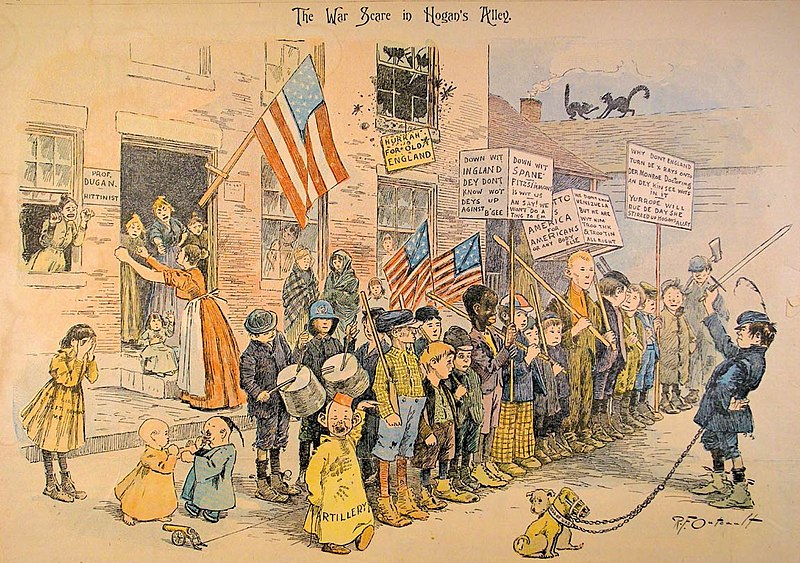

One of the first regular cartoons to appear in the World was Hogan’s Alley by R.F. Outcault (1863– 1928), featuring comic vignettes of the slums.

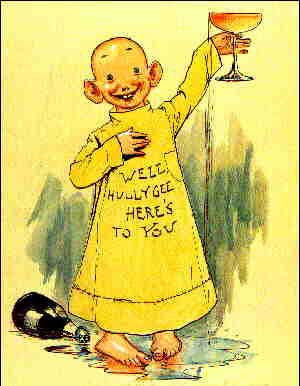

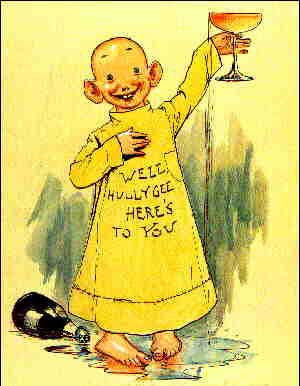

The hero of the cartoon soon came to be a rascally urchin called ‘The Yellow Kid’:

Hearst lured Outcault and his cartoon away from the World; Pulitzer sued; the upshot was that Pulitzer continued Hogan’s Alley, now drawn by George Luks, while Hearst published Outcault’s version under the title The Yellow Kid.

The traditional press looked on these vulgar papers with distaste. In an 1897 article in the New York Press, veteran newsman Ervin Wardman attacked Pulitzer and Hearst for their “yellow kid journalism”. Shortened to yellow journalism, the phrase still designates sensationalist, populist media reporting, whether in print or on the air… or on the Internet.

” The entire filing system has to be fixed — as it is, it’s as screwed up as Hogan’s goat.”

Outcault’s strip also gave rise to an expression especially popular in the Armed forces, particularly the Navy.

Hogan’s Alley had a smelly, bad-tempered goat in residence.

Any situation that is seriously fouled-up is said to be as f—ed up as Hogan’s Goat.

However, another famous Outcault creation– Buster Brown— was not, as some say, the source of the nickname and epithet ‘Buster’, which had existed years before he drew the strip.

************************************************************

“Wimps, I think; milquetoast souls who cough if someone is smoking across the street, who wear cardigans and bicycle clips; for god’s sake, if you’re so delicate, move to an ashram!”

—George Michelsen Foy, Zero Decibels

The disparaging word (noun and adjective) “milquetoast“, evoking weak-tea wimpiness and pusillanimity, comes to us from Caspar Miquetoast, the pathologically shy and timorous ” hero”, courtesy of H.T. Webster (1885 – 1953), of the weekly comic panel, ‘The Timid Soul‘. Milquetoast: it’s a word often used for so-called “henpecked” husbands in the Walter Mitty vein.

“Voters in this election were almost all polled at saying they were sick and tired of milquetoast congressmen: they wanted rebels with the guts to challenge the status quo”.

As my composite example attests, it has been trotted out repeatedly in the 2010 midterm congressional election: google “milquetoast politician/congressman” for examples.

********************************************************

“He spent the whole vacation complaining about the weather and worrying about the cost; it’s no fun having a gloomy Gus as a travelling companion.”

The appellation gloomy Gus for a depressed, pessimistic individual comes from Frederic Burr Opper (1857 — 1937)’s strip Happy Hooligan. Gus was one of the brothers of the hobo title character, and indeed he was in a perpetual state of gloom; ironically, he always fared better than the optimistic Happy or the pretentious other brother, Montmorency, in their calamitous adventures.

Copyright registration for a Gloomy Gus doll.

In the panel below, Gus is at far left, next to Montmorency with Happy at the kissing booth at right.

****************************************************************

“Enter a haunted house? After you, my dear Alphonse!“

Another Opper strip gave us a lasting idiom: Alphonse and Gaston. It was a one-gag concept, featuring two Frenchmen who would waste time insisting, with preposterous courtesy, on the other’s precedence even in the direst situations.

A situation where neither side will take the first step in concerted action is often called an Alphonse- and- Gaston situation:

“Both Democrats and Republicans agree the budget must be reduced, but neither party wants to be seen cutting popular programs such as Medicare; thus the Alphonse-and- Gaston standoff in the House.”

****************************************************************

“One of the FBI interrogation techniques is the old Mutt-and-Jeff routine taught by Army intelligence.”– Washington Post, 30 August 1964

Mutt and Jeff was an immensely popular strip by Bud Fischer (1884 — 1954), featuring the adventures of a comically mismatched duo of friends, tall Mutt and small Jeff:

This physical disparity ensured that any pair of height-mismatched companions in America would be dubbed “Mutt and Jeff”.

This physical disparity ensured that any pair of height-mismatched companions in America would be dubbed “Mutt and Jeff”.

The two differed in character, too. Mutt fancied himself a sharp operator, quick with schemes to turn a fast buck, preferably at the racetrack. Jeff was a gentle soul, something of an innocent, whose unworldliness would frequently derail unwittingly his compadre’s latest scheme, to the latter’s exasperation.

In police slang, the “good cop/bad cop” interrogation technique was logically dubbed a Mutt-and-Jeff routine”

************************************************************

“First you think we’ll miss the plane, then you’re afraid it’s overbooked– honestly, you’re such a worry wart!“

Art by J.R. Williams

From 1922, the cartoon panel Out our Way, drawn by J.R. Williams (1888– 1957) celebrated the foibles of life in small- town America. A recurring character was the boy dubbed the Worry Wart, because he created so many worries among others. When worry wart entered the language about 1956, the sense had shifted to one given to excessive worrying.

(Another Williams catch-phrase much beloved of my mommy was “Why mothers get gray“, trotted out at any egregiously foolish conduct on my part.)

*************************************************************

“He set up his own pump-and-filter system cobbled out of reclaimed junkyard parts; I’ve never seen such a crazy Rube Goldberg contraption.“

Sometimes it’s the cartoonist who gives his name to the idiom.

Rube Goldberg (1883 — 1970), a prolific cartoonist with a long career, is best remembered for his designs of insanely complicated machines, made of ridiculous parts, to accomplish trivial feats like knocking on a door or catching a mouse.

Here’s Goldberg’s idea of an alarm clock:

Any over-complicated, jury-rigged machine or system is apt to be tagged a Rube Goldberg contraption. ( We also refer to bureaucratic systems of insanely complex red tape as Rube Goldberg systems.)

I recall, as a child, being inspired by these cartoons (and by the Goldberg-derived game ‘MouseTrap‘ — does anyone else remember that?) to build my own nutty contraptions. I’ll wager Goldberg inspired many a future inventor or engineer.

Since 1949, Purdue University has run the Rube Goldberg Machine Competition, where contestants are assigned a simple task to be carried out by a machine; the most absurdly complicated machine wins.

At the 2007 competition, this device was for pouring orange juice into a glass:

************************************************************

This was part 1 of a seven-part weekly series. In part 2, we’ll cover the great age of the comic strip…from Popeye to the Dragon Lady and beyond!

See you in the funny pages!

************************************************************

This is part one of a seven part series; click here for part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5, part 6,part 7 and an index.

Part 3 concludes our look at strips; parts 4 and 5 cover the comic book; part 6, gag and editorial cartoons; part 7, British and Commonwealth cartoons; and I would like to have a part 8, consisting of French, Italian, and other European colloquial languages enriched by their cartoons.

Friends–I need your help!

If you have any suggestions for cartoon-derived idioms along the above lines, please mention them in comments– or e-mail me at the yahoo dot com address alexbuchet

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Here are some useful and interesting online resources for language:

The blog wordorigins tracks current and historic words; its index of words and phrases The Big List is guaranteed to keep you riveted for hours.

Oh, and congratulations to Craig Yoe and Clizia Gussoni on the birth of their son Griffin! Mazel Tov!