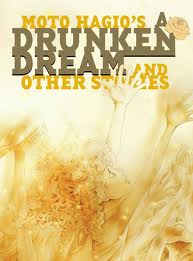

Editor’s Introduction: This month’s “Sequential Erudition” features Ariel Kahn’s paper originally presented at the IBBY UK/NCRCL Conference last November. We choose it for this month’s column because its use of Laura Mulvey’s concept of the “gaze” fits with Noah’s recent post on Moto Hagio here at HU and a number of comment conversations. Personally, I appreciate the way Kahn combines thematic and formal analysis in combination with theoretical texts to make his point and provide an engaging essay. We’ll still looking for more papers for future columns, so if any academics out there would like to participate, leave a message. -Derik.

Reading Between the Lines: The Subversion of Authority in Two Graphic Novels for Young Adults by Ariel Kahn

Originally presented at IBBY UK/NCRCL Conference, 14 November 2009 at Roehampton University, London.

A recent resurgence in the publication of comics and graphic narratives specifically aimed at young adults raises a range of issues about the nature of authority, and the role of the reader in negotiating the narrative and constructing meaning in and through the interplay of image and text. This paper explores the diverse relationships between image and text, and the implications of the enhanced role they create for the reader.

The Problematics of Children’s Literature

The notions of authority and of the relationship between writer and reader are central to critical discussions of literature for children and young adults. This is evident in the contrasting positions taken by Jacqueline Rose (1984) and Peter Hollindale (1997). Rose argues that ‘children’s fiction is impossible … it hangs on an impossibility, … this is the impossible relationship between adult and child’ (1984: 1). The use of the author’s adult authority to shape and instruct the reader leads Rose to view children’s literature pessimistically as an act of repression. In contrast, in Signs of Childness in Children’s Books, Hollindale defines the divide in critical focus in children’s literature as existing between those who ‘prioritise either the children or the literature’ in the study of children’s literature (1997: 8). He advocates instead a study of children’s literature as a ‘reading event’ (p.30) in a strategy that allows both the child and the text to have a place.

Image/Text Relationships in Picture Books and Comics

The possibility of such a ‘strategy’, and the exploration of the narrative possibilities of such a ‘reading event’ are, I will argue, particularly striking in comic books written for young adults, picture books in which the active engagement with image and text opens up a multiplicity of possible readings, rather than enacting the closure and repression of which Rose warns. In How Picturebooks Work (2001) Maria Nikolajeva and Carole Scott identify ‘a taxonomy of picture book interactions’, which places the interactions of image and text on a sliding scale from Symmetry, to Enhancement, Counterpoint, and Contradiction. The authors are most interested in those picture books that use ‘counterpoint’, i.e., when ‘words and images provide alternative information or contradict each other in some way’ (Nikolajeva and Scott, 2001: 17, quoted in Donovan, 2002: 110).

Continue reading →