Bruno Lecigne’s “De la confusion des languages” (on the mixing up of the languages)

My monthly stumblings are, sometimes, restumblings, really… This past weeks I restumbled at least twice: on Otto Dix’s Der Krieg (the war) and Bruno Lecigne’s “De la confusion des languages” (Controverse – controversy -, May 1985). In “De la confusion…” Bruno Lecigne presented eight chapters about comics criticism. I will summarize them trying to avoid misrepresentation:

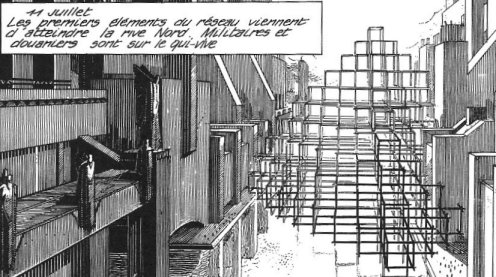

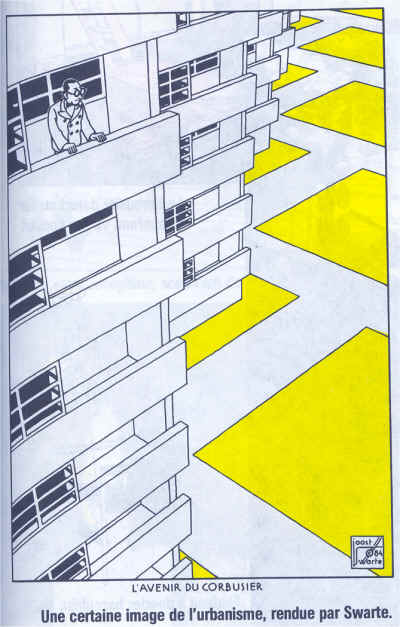

(I) After being a subculture designed to amuse children comics reached adult readers and achieved official recognition in France. This meant that, after being devalued in their totality, comics started to be valued also in toto. It’s the amalgam: “there’s a distortion between the genre’s reality, which is multiple, and its image, which is assembled.” This means that a comics auteur is just a comics professional. It doesn’t matter if s/he does stereotyped products for children (normalized distractions for everyday consumption) or ambitious, personal work: “there’s confusion between the “auteur” as a professional (social status) and/or as a creator (artistic status)[.]” This means that institutional prizes and grants are given both to innovative, personal, work and commercial successes without any creativity. It also means that critics value everything, without any criteria.

(II) Comics in France started by being an infraculture rejected by the official instances. Academia either ignored or denigrated them. In the latter case academics based their attacks on three major points: comics are morally corrupt; comics are culturally harmful because they deturn from the real culture (particularly from literature); comics are aesthetic junk. Facing this rejection and suffering from a lack of legitimization the comics fans are going to organize a milieu in which a parallel legitimization is going to appear (through magazines, fanzines, conventions, collectors, specialized critics; everything in closed-circuit): a paraculture was born (the word “subculture” could also be used, I suppose). This subculture is not completely watertight though: some intellectuals will function as ambassadors to the mainstream media and academia. They will defend comics as: 1) just another art form; 2) unpretentious and fun; 3) ultraculture (the underground).

(III) There’s no objective reality of artistic creation. Concepts like “auteur” or “producer” are historically determined. They’re part of a mentality, of an ideology. Denouncing the mixing up of the criteria means denouncing a cultural manipulation: “a morality of consumption can’t be, without deception, credited to an ideal of creation.” The social status of the artist varied through history: “archaic phase: the wizard; classical phase: the craftsperson; Romantic phase: the artist; modern phase: the creator.” These categories are sociological, not artistic. These historically determined concepts may be seen as “values” and used retrospectively (e. g.: the work of Alfred Hitchcock or Howard Hawks seen as auteur creations). “All speech about art presupposes an implied or confessed ideology which supports economical strategies within the field, new to comics, of the institutionalized culture. The brand of creation is bandied about indiscriminately by certain editorial policies [.] […] The propaganda of cultural activities, for instance, dissimulates a real practice of commercial criteria – these contradictions […] are stifled by the amalgam though.”

(IV) The reviews are the privileged place of the mixing up of the languages: two examples: an anti-intellectual review in (A Suivre) (comics are fun and intelligent means boring) and a review in L’Année de la bande dessinée 84 – 85 in which the writer (Thierry Groensteen) praises François Bourgeon as a craftsman to claim his status as an auteur afterwards. He bases his claim in nothing: “Bourgeon is an auteur because he is an auteur.”

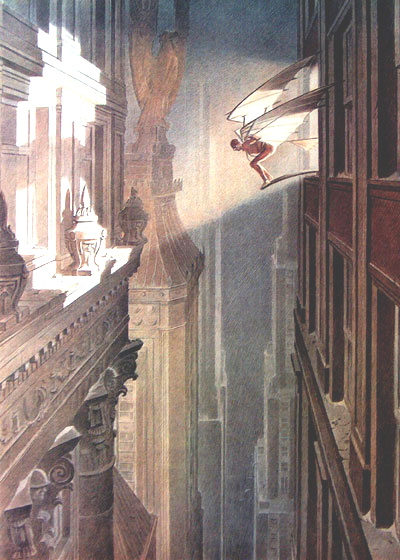

(V) In this day and age we view creation as a detachment from commercial constraints. In the comics milieu it’s rarely the case: even Tardi (with Adéle Blanc-Sec) and Chantal Montellier (with Andy Gang) must submit themselves sometimes to the restrictions of the series. Auteurs should also be free from editorial policies, but, again, that doesn’t happen a lot. The point isn’t that commercial and editorial constraints lead to an inevitable lack of quality. “What’s questionable is a speech based on the freedom of creation which cannot be valid because it hides “industrial” constraints and imposed rules – self-imposed or not.” An autor like Tardi (or Guido Buzzelli, sez I), is in a schizoid position: his personal work coexists with his alimentary production. “[A] dynamism art/commerce is, as everywhere else, sustainable, but its ambivalence, if doctored by a speech, is a falsification.”

(VI) New approaches to art creation include the viewer as “producer of meaning” and stress art’s polysemy. As Revault d’Allones put it: “The abuse that constitutes calling works of art productions may allow an ideological manipulation in reverse: mistaking industrial products for works of art, veiling, in this way, the nakedness of the profit under the patched vest of beauty.” […] “The problem is not to determine which doctrine of creation is the “true one,” or the more adequate to comics (where all strata coincide: production / mass consumption, innovative or avant-garde explorations, fetichization, etc.), but to dispute the mixing up of the languages, namely the absurd support that a global positive cultural image gives to production conditions that are just commercial. The “vest of beauty” may not fit on everybody, that’s normal; but the universal acceptance of clichés may dress everybody and that is a pity, or it is indeed sinister.”

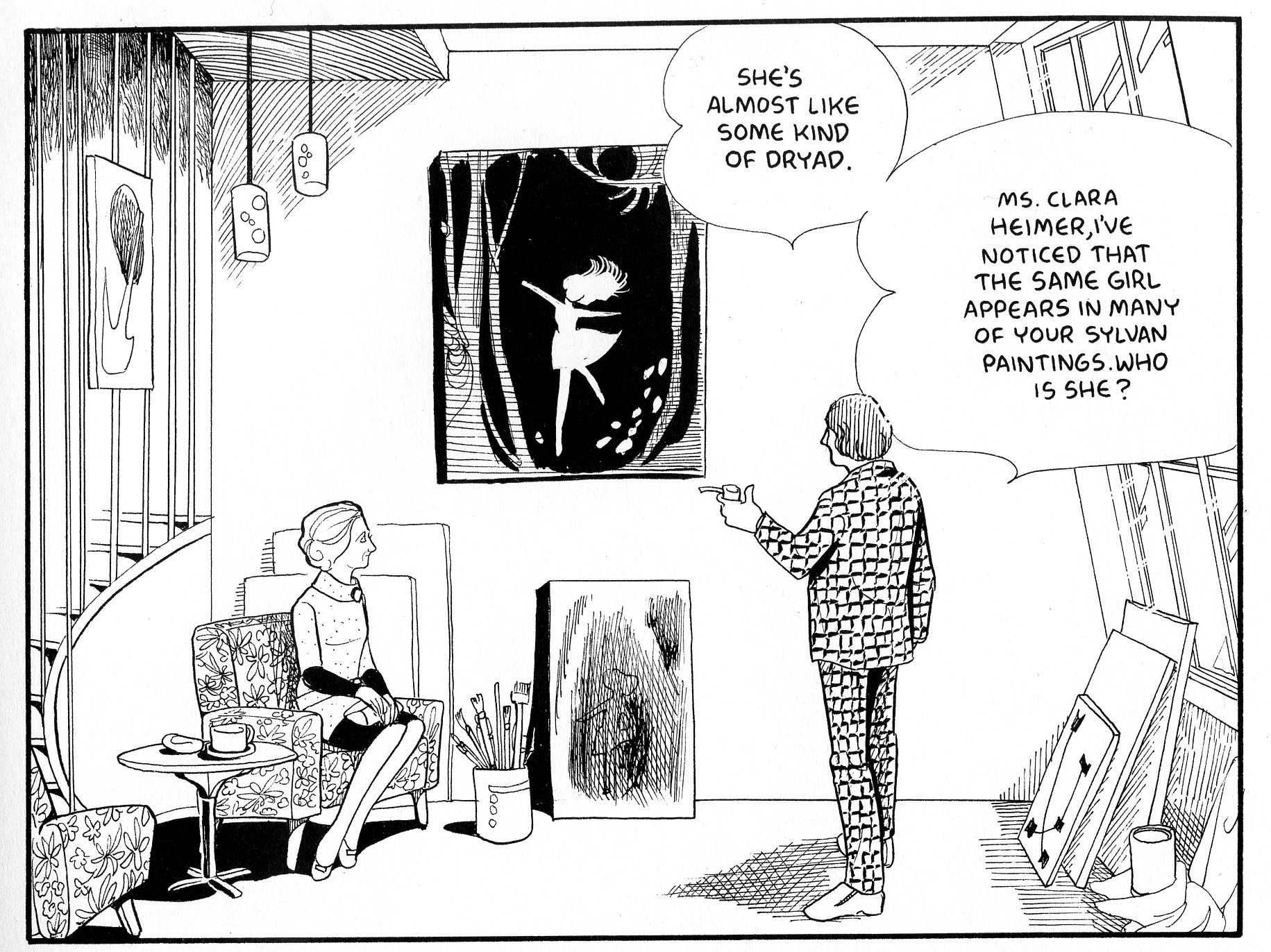

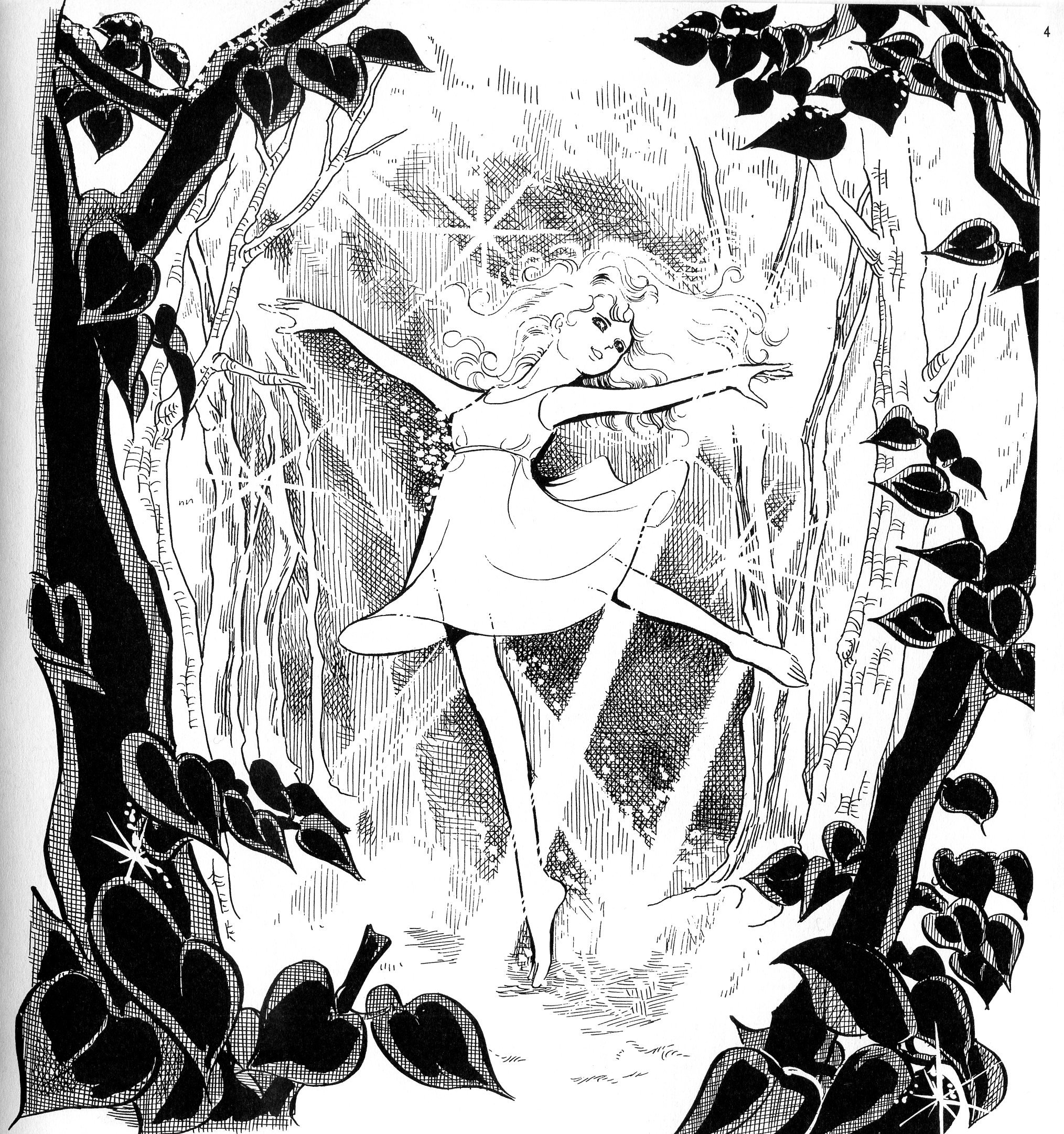

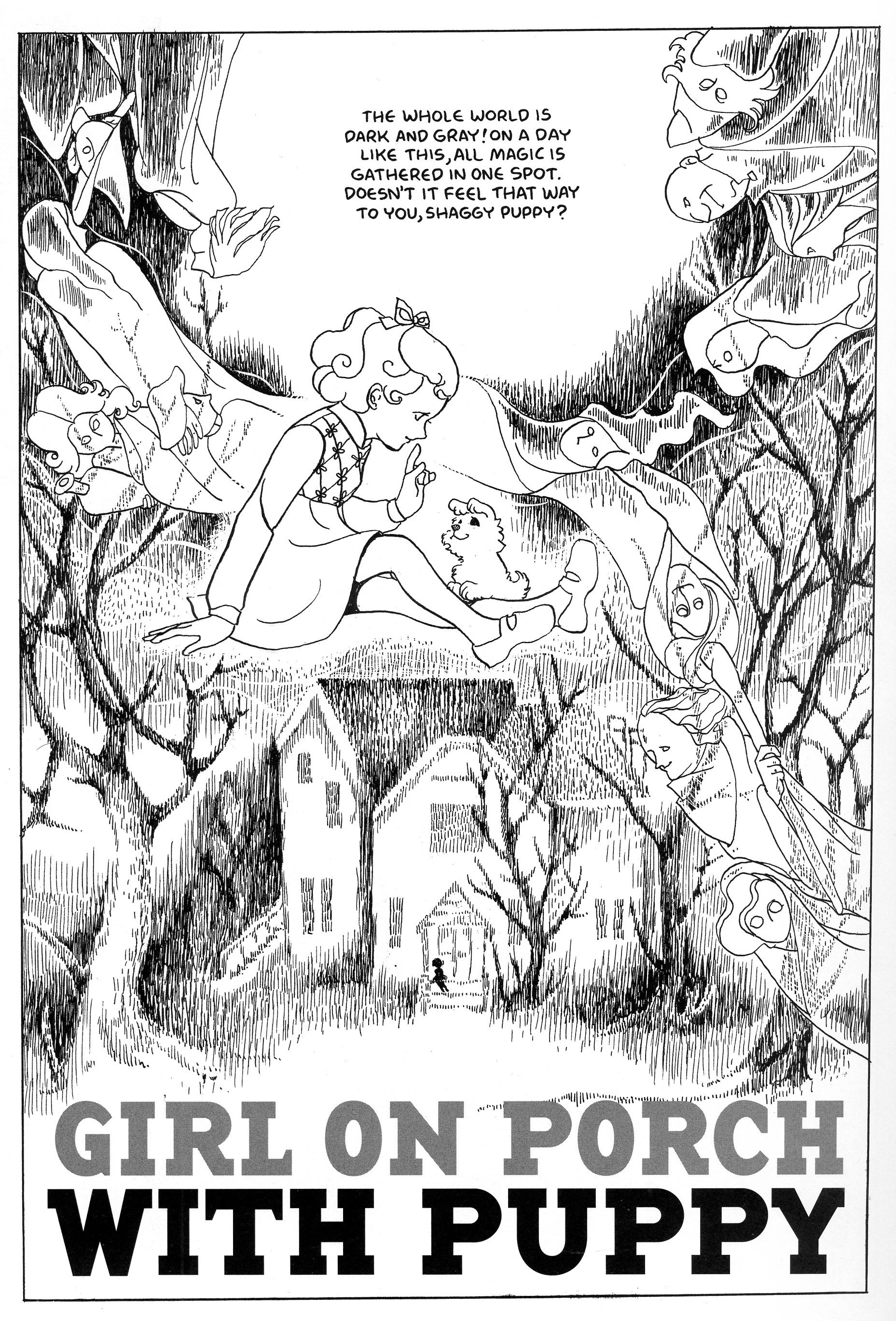

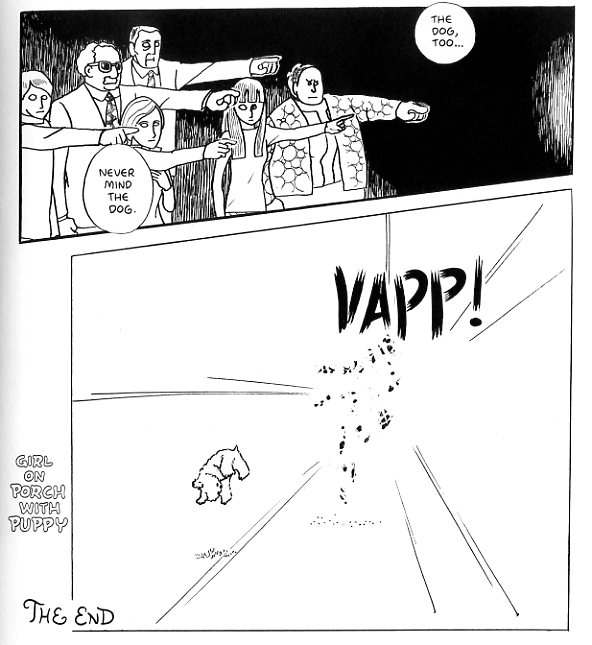

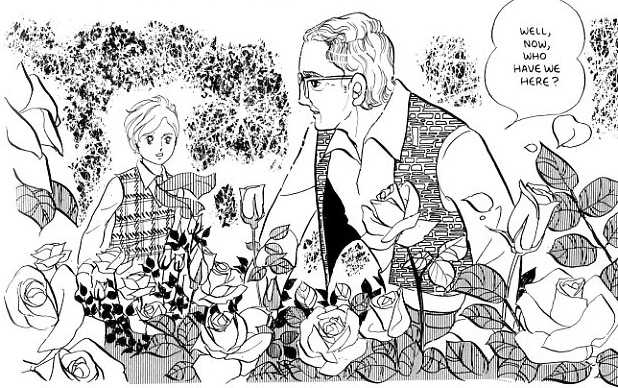

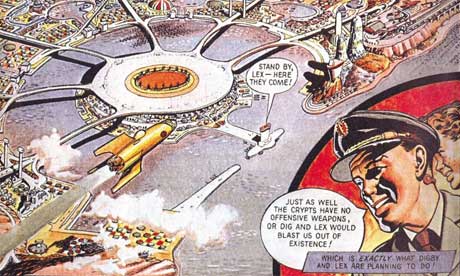

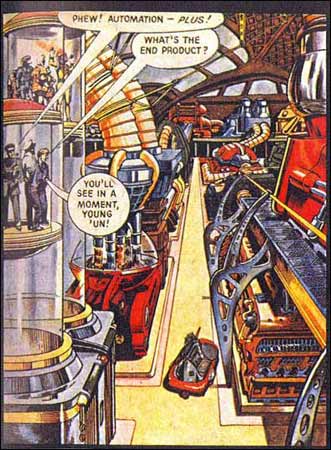

(VII) If real comics criticism doesn’t exist what passes for comics criticism in the media does have a strong presence. It privileges the adventure series for children: “escapist comics guided by the stereotypes of the heroic fantasy where the image is in the service of the anecdote, without an aesthetical surplus. Being an easily digestible product it implies a consumer’s reading: at the first degree of the narrative’s transparent content, evaluating the images by their effectiveness and their “prettiness.” These rules of the readers are also, quite often, those of the critics who are going not to distance themselves, but to reiterate these principles fixing them in a speech.” The escapist series becomes the epitome of comics greatness. “Integrating has their sensitive model the laws of the series, critics are in accordance with commercial recipes, to which they give the legitimation of the “artistic” speech and the “cultural” value judgment: here’s the language of the mixing up.” Comics critics are also archivists and hagiographers.

(VIII) After a feminist manifesto by four French comics artists (Nicole Claveloux, Florence Cestac, Chantal Montellier, Jeanne Puchol) published in the mainstream newspaper Le Monde (1985) anti intellectual attacks followed (feminists lack humor and comics are fun, as we already know!): “[the manifesto] rubbed the wrong way a certain mantra of self-satisfaction; instead of linking filled box-offices with creative qualities, variety of style, contemporary inspiration, the Monde‘s page links it to clichés, uniformity, poor imagination or complete absence of imagination in favor of a cocktail of formulas.”

To fully understand the above we need to go back 25 years and understand its social and historical context. It’s a controversial text, almost like a manifesto, because Bruno Lecigne felt during the eighties that the revolution which started a decade earlier was being stifled by the temple sellers. In his interview with Jean-Christophe Menu (L’éprouvette # 3, January 2007) he calls the eighties “les années fric” (the dough years). On the other hand I will not underline enough the fact that this is my selection, my reading of Bruno Lecigne’s text, not the text itself, obviously.

Is the divide between art and commerce that wide? Bruno Lecigne himself says that it isn’t. He wanted to attack comics’ pseudo-critics and their blindness, not any artists (he even says that commercial and editorial constraints may lead to quality books). The problem is that citing Hitchcock and Hawks, as he does, without questioning (or not) the Cahiers du Cinéma‘s legitimacy to call auteurs to these directors (or, at least, to write briefly about the subject) undermines a bit, in my opinion, Lecigne’s points. These are painfully difficult questions and things seem (even if they aren’t) too clear cut in “De la confusion…”

That said I’m fully with Bruno Lecigne, as all of you who are still reading know perfectly well. I think that the movie industry didn’t impose as many stereotypes and formulas to Hawks and Hitch as the comics industry does to their hired hands (as Lecigne also says: enforced from outside or self-imposed doesn’t really matter).

Did things improve during the last twenty five years? I don’t think so. Amalgamation is still being practiced and a lot more pseudo auteurs are being lauded than the real ones (as the year 2000 lists painfully proved to me; I don’t know if comics critics are viewing things differently ten years later, but I doubt it). The best though is to listen to Bruno Lecigne himself because Jean-Christophe Menu asked him just that in 2007: “There was, back then, a clear cut frontier between what was “culture” and what was not. That line doesn’t exist anymore. […] Everything that was minor or subculture […] lives perfectly well, in a general way, in a global production and consumer system of “cultural goods” and “cultural contents.” […] There’s an openness which is the one we fought for, but the other side of the coin, that we didn’t predict, is that everything is equal to everything. […] There’s a generalized softness, everything floats with its bellies up, without determination, without any definition. The great antagonisms ceased to exist. Since comics won the economical combat in France (it’s a profitable part of the book industry), it won its cultural combat as well at a moment in which it doesn’t matter anymore.”

Can you find a more pathetic irony?