On Wisconsin Public Radio’s Here on Earth program — moderated by the able Jean Feraca — Gene Kannenberg and I chat about Tintin and field listeners’ calls; you can find a streaming of the show at this link.

Enjoy my dulcet tones– or, rather, my robotic stammer.

———————————————

Some have chided me for overlooking the most excluded of “others” in the Tintin oeuvre, i.e. women.

This is indeed true. In all the albums, there are only three or four women with so much as speaking roles. I interpret this as a hangover from the fiercely puritanical Catholicism of Hergé‘s youth, mixed with his own dose of misogyny. Hergé’s own explanation fails to convince:

“True, there are only a few women, but not out of misogyny. No, it’s simply because as far as I’m concerned, women don’t belong in a world such as Tintin’s; it’s one dominated by male friendship, and there is nothing ambiguous about such friendship! Of course there are only a few women in my stories and when they do appear, they are caricatures, such as Castafiore.

If I were to create a character who was a pretty girl, what would she do in a world where all the other characters are caricatures? I love women too much to turn them into caricatures!

Anyway, pretty or not, young or not, women are rarely comical elements.

Would it be the maternal side of women which prevents us from making fun of them?”

(That last sentence would be of interest to a psychiatrist…and, indeed, Hergé spent years in analysis.)

But there is one woman in Tintin with enough force and character to dominate any story she shows up in; yes, the divine ‘Nightingale of Milan’, the Empress of the Opera:

Bianca Castafiore!

What mere male can fail to wilt before such beauty and power?

As the good Captain Haddock says, a formidable woman.

Ah, Captain, submit to the inevitable; the charm and might of La Castafiore will keep you in her thrall!

The transition from ogress to goddess is most satisfying, and is consummated in Hergé’s wittiest Tintin album, Les Bijoux de la Castafiore (‘The Castafiore Emeralds’)

Love her though I do, I must concede that the Castafiore is a monstrous caricature of woman.

What I delight in, however, is the way she serenely floats above every catastrophe…even when on trial for her life (in “Tintin et les Picaros”) she turns the courtroom into an opera stage!

You go, girl!

————————————–

Tintin wasn’t Hergé’s only series.

One may applaud the cosmopolitanism of the later Tintin albums (and of the redacted earlier work), yet still regret a certain earthy malice inherent to the initial work: Tintin was, in the beginning, a brawling, cunning trickster more than a boy scout. He was also definitely Belgian, as contrasted with the somewhat bland “international” Tintin of later years.

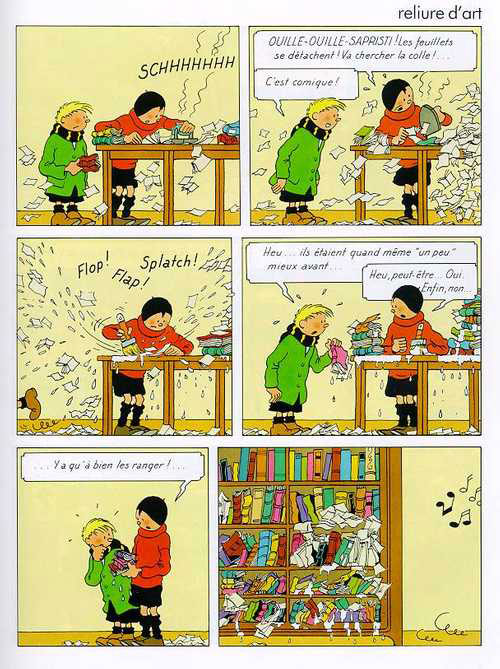

As a counterpoint, I recommend (to you who speak French) the series of albums featuring Quick & Flupke, a pair of wicked little Brussels street urchins.

The Belgian equivalents of the Katzenjammer kids or of Max and Moritz, these two lively pests were well grounded in the rich culture of that teeming capital, Brussels.

The series, composed of two-page stand-alone gags, also lets Hergé indulge one of his major talents as an entertainer– the gagman… but in a childlike, gentle mode that didn’t exclude mild satire:

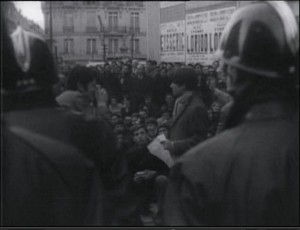

And the establishment– represented by the police– comes in for some tweaking at the hands of this delinquent duo:

Try this strip some time!