So many crime comics, so little time. Vertigo alone must publishes half a dozen pulp crime monthlies, and that doesn’t even include the Vertigo Crime imprint. I already reviewed one of the Vertigo Crime graphic novels here, so I’ll limit this post to monthly titles.

Reviews

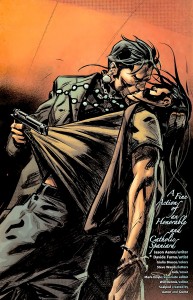

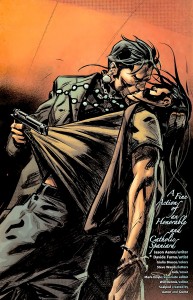

Choker #1

Writer: Ben McCool (that can’t possibly be his real name)

Artist: Ben Templesmith

Publisher: Image Comics

Crime and horror are an unlikely pairing. They may share an appreciation for violence and brooding scenery, but the primary appeal of the genres are at odds. Crime stories are generally empowerment fantasies, whether the focus is on the criminal (empowerment against authority) or the detective (empowerment in service to authority). Horror is more about powerlessness, and the thrills and scares that come from being vicariously helpless. These are two genres that just don’t mix well. (Now, some of you will argue, “What about Seven? That had detectives and it was scary up until the moment the killer was revealed to be Kevin Spacey.” But Seven wasn’t really a crime story, because the detective scenes with Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman were not critical to the film’s appeal. They just filled in time between the big gross-out moments). All of this is a roundabout way of explaining why Choker is not a good comic.

Set in the future, the plot follows a lowly private detective named Johnny Jackson. Formerly a cop, he’s given an opportunity to get his old job back if he can capture a drug dealer. About as basic a crime plot as they come, but the story quickly veers towards horror because the drug in question transforms its users into something akin to vampires.

The horror factor is also emphasized by the artwork. Ben Templesmith is best known for his work on several popular horror comics, particularly 30 Days of Night. His art in Choker looks very similar: distorted bodies, the heavy use of black, grimy backgrounds. Though in Choker, he also uses lurid red and orange coloring to highlight the corruption and decadence of the future.

It looks very cool, but the flashy art can’t hide the fact that the comic doesn’t function well as either horror or crime. The horror aspect is undermined by the concepts inherent in a crime story. For example, by focusing the plot on the hard-boiled detective, McCool deflates any anxiety that the reader might have, because we all know that the chain-smoking tough guy isn’t going to die. At the same time, the crime story is diminished by the comic’s awkward attempts at being scary. The vampires in the story are meant to be creepy, but they’re really just super-powered junkies. It’s impossible to take the central conflict seriously. The book has a lot of ideas, but they remain incoherent and poorly executed.

Criminal – The Sinners #1

Writer: Ed Brubaker

Artist: Sean Phillips

Colorist: Val Staples

Publisher: Icon (Marvel)

Criminal is one of the least innovative comics being produced by any mainstream publisher. Ed Brubaker writes stereotypical crime stories: square-jawed protagonists, femme fatales, and endless monologues. Sean Phillips and Val Staples illustrate the comic in the most predictable manner possible: dark colors, thick black lines, a general impression of an overbearing world. We’ve seen this all before.

The plot of this issue is also familiar. Tracy Lawless (a character from an earlier story arc) is stuck working as a hitman for a mob kingpin. He’s offered a chance to walk away, but only if he can figure out who’s murdering the mobster’s lieutenants. It’s a typical anti-hero plot, with the obligatory sub-plot involving the mobster’s sexy wife.

Brubaker and company aren’t doing anything new or original – and that’s okay. So what if they don’t re-invent the wheel? Wheels already do exactly what they’re supposed to do. I suppose I should laud innovation, but to be perfectly honest I’m only interested in innovation when it produces a great story. If creators tell a great story by inventing an entirely new genre of entertainment, then I’m happy. If creators tell a great story by relying on familiar tropes from a well-worn genre, then I’m happy.

Brubaker may not be an innovator, but he’s a reliable craftsman. The characters are all archetypes, but they’re enjoyable archetypes that fit perfectly into the world that Brubaker and Phillips have created. The plot is predictable, but it plods along with the implicit assurance that the payoff will be worth the wait. And while Phillips isn’t a daring artist, his pencils and inks effectively conveys both story and tone.

Criminal is nothing more and nothing less than the work of professionals who are doing exactly what they want to do.

Scalped #36

Writer: Jason Aaron

Artist: Davide Furno

Colorist: Giulia Brusco

Publisher: Vertigo (DC)

I’m not a regular reader of Scalped, but from what I’ve seen of the series I’m pretty sure it’s about Native American gangsters who run a casino. I think I read a review that described it as Sorpranos on an Indian reservation (hopefully without the pretentious dream sequences), or maybe it was Goodfellas on a reservation. But since it involves a casino, perhaps it should be Casino on a reservation. Scalped readers need to help me out here. What is the proper analogy? And is there an Indian Joe Pesci?

The first thing that came to mind as I read this issue: Scalped is a remarkably exploitative comic. A team of white creators produced a story about violent, lusty ethnic minorities who kill and fuck each other for the amusement of the predominantly white audience. And they even throw throw in a nod to Indian spirituality (one character actually narrates from beyond the grave). I suppose I should find all this offensive, but I’m actually impressed that Vertigo published a comic about Indians that didn’t involve Jonah Hex shooting them.

And once you get past the Indian-sploitation, it isn’t half bad. It has all the elements readers would expect from a gangster comic: sleazy casino owners, brutal violence, macho men. And there are a few things readers wouldn’t expect, such as the fact that the macho men enjoy gay sex.

The art is okay, in the way that art in Vertigo comics is always “kind of,” “sort of” okay. Davide Furno deserves some small praise for his character design, because at least Native Americans don’t look like white people with tans. But the art isn’t memorable in any way, which is the harshest thing I can say about it.

So this is a comic about gay, Native American gangsters, and (lackluster art aside) it truly is the best damn comic about gay, Native American gangsters that I’ve ever read.

_____________

State of the Genre: For a genre that was once almost completely absorbed by superheroes, crime has made a massive comeback. In itself, the success of the crime genre is hardly surprising. Stories of crooks and heists and square-jawed detectives have remained popular in every other media for decades. What is surprising is just how long it took for crime to recover as a prominent genre of American comics. Blame Wertham, the Comics Code, superhero fanboys, etc., etc.

But over the last couple decades the comics market has evolved to the point where it can sustain a significant number of crime comics. And given the size of the genre, it deserves an extra post, which is why I’ll be reviewing Peter Milligan’s Bronx Kill next week.