This week, I’m reviewing five recent horror comics. Unlike barbarian comics, which I discussed back in January, horror comics are not scarce. It seems every publisher has at least a couple horror titles, and in the case of some of the smaller publishers (IDW, Devil’s Due), the majority of their comics are horror. However, as many as a third of these titles are licensed properties (that is, they’re based on movies or video games). I chose to review only original creations, not because they’re inherently good, but because I’m more interested in stories that are specific to comics. These five titles aren’t necessarily the best or the worst, but they are indicative of what American publishers are releasing in 2010.

Reviews:

Hellblazer #264

Publisher: Vertigo

Writer: Peter Milligan

Layouts: Giuseppe Camuncoli

Finishes: Stefano Landini

Colors: Trish Mulvihill

What’s the division of labor between the artist who does layouts and the artist who “finishes?” I assume the layout artist determines the shape and number of panels on each page, and perhaps also the contents of each panel. The finishing artist then adds the necessary details (or is my assumption completely wrong?). This could lead to some awkward, ugly comics if the two artists have different styles. But this is a Vertigo comic, and most of the artists who work for Vertigo tend to use the same semi-realistic, functional style that effectively conveys the story without drawing attention to itself. Camuncoli and Landini work well together, and they produce a comic that’s clear, consistent, and bland.

As for the story, this issue is the final chapter in a storyline within a book that’s been published continuously for two decades, so it isn’t exactly a great jumping-on point (and no recap page, because DC/Vertigo thinks recap pages are for wimps). Still, Peter Milligan is an experienced mainstream comics writer, and he knows that every issue is someone’s first, so he provides narration at the front of the book that helps new readers catch up. The plot, in a nutshell, is about John Constantine fighting a Victorian-era demon in Mumbai. Like the art, the writing is polished and professional, though not particularly memorable.

While it’s also tempting to complain that the story is predictable, predictability is really the whole point. Hellblazer, like most long-running titles, is comfort food for fans, and Milligan knows where and when to deliver the expected beats of a John Constantine story. There are demons, spells, smoking, and British profanity. But the old, reliable formula that makes it good comfort food also makes it terrible horror. Horror works best when it exploits the fear of the unknown and the unexpected. This is why horror film franchises quickly descend into self-parody – once the monster is revealed in the first film, the audience no longer fears it, so the sequels are just the repetition of events that are humorous and comforting precisely because they’ve lost the ability to scare. Milligan’s take on Hellblazer avoids becoming a self-parody by simply abandoning any pretense at being scary. It’s a magic-themed action/adventure that’s indistinguishable from the superhero titles published by DC, except that the characters get to say “fuck” instead of “#&$%.”

The Walking Dead #70

Publisher: Image

Writer: Robert Kirkman

Artist: Charlie Adlard

Gray Tones: Cliff Rathburn

According to the Direct Market sales charts posted at The Beat, The Walking Dead is one of Image’s best-selling monthly comics. Which is bizarre, because if there was ever a comic that should only be read in collected volumes rather than monthly issues, it’s The Walking Dead. Kirkman’s pacing ranges from leisurely to glacial, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing in a longer book. The horror of The Walking Dead has less to do with the zombies than with how their ever-present threat transforms the survivors. Over the course of a trade, readers can appreciate how all the characters (or at least the ones that don’t get offed) slowly change, usually for the worst, in response to the collapse of civilization. But it’s hard to get any sense of that in a typical monthly issue, which has only a small portion of the plot and character development. Issue #70 is a perfect example: the survivors are welcomed into a walled, zombie-free community and meet the community leaders (who will probably turn out to be evil). That’s it. In another six to twelve months this might become an interesting story, but I can’t imagine paying $3 a month for snippets of content.

The art in the issue is easier to discuss. Adlard’s style is thoroughly mainstream, meaning a realistic aesthetic and a simple panel layout that moves the narrative forward. The one unusual aspect of the art (by the standards of mainstream American comics) is that it’s in black-and-white.

This was a clever creative decision, as the black-and-white gives The Walking Dead an earthy, retro vibe reminiscent of the classic zombie film, Night of the Living Dead. But setting aside the pop culture homage, Adlard rarely does anything interesting with the black-and-white format. On occasion, he’ll use dark inks and sharp contrast to evoke a film noir tone, but most of the panels wouldn’t be harmed by the addition of color. In other words, the art does what the story requires of it, nothing more and nothing less.

The Unknown – The Devil Made Flesh #4

Publisher: Boom! Studios

Writer: Mark Waid

Artist: Minck Oosterveer

Colors: Andres Lozano and Javier Suppa

The first thing I noticed about The Unknown is that it has a recap page that efficiently summarized the previous three issues. As a new reader, I liked this feature. I will never understand why DC and a few other publishers refuse to include recap pages. If you insist on publishing monthly issues, then why not throw new readers a bone? Not everyone can jump in on the first issue.

The story centers on Catherine Allingham, a detective who’s slowly dying from a brain tumor. On top of that problem, she’s been dragged into a mystery involving a small town serial killer and a ghost that keeps possessing the townspeople. It ends with a big battle in a cave and some revelations about future storylines, which may involve the Devil (made flesh). Like most contemporary comics, The Unknown has a “decompressed” pace, meaning that the plot and characters are gradually developed over multiple issues. But unlike Robert Kirkman, Waid knows how to squeeze as much content as possible into 22 pages. Reading a single issue of The Unknown feels like reading four issues of The Walking Dead.

But more content doesn’t equal better content. Waid’s writing has always beens mechanical and generic, like he’s working from a genre checklist. Characters do exactly what readers expect of them, and plots resolve themselves in the simplest manner possible. The Unknown is no exception: the central conflict ends with a violent climax, the villains get their appropriate comeuppance, and a sufficient amount of information is revealed to move the larger story forward.

The art doesn’t help matters. Oosterveer attempts a straightforward, mainstream style, but his art comes across as amateurish. Spatial relationships are confusing, backgrounds will be drawn in detail in one panel but disappear in the next, and the characters’ faces frequently go off-model. To put it simply, the entire comic just looks half-assed and rushed.

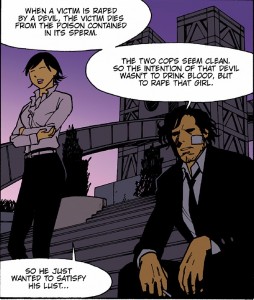

Devil #1 (of 4)

Publisher: Dark Horse Comics

Writer/Artist: Torajiro Kishi and Madhouse Studios

Someone at Dark Horse decided that they needed a new horror comic, something fresh and original. And where are all the fresh and original ideas coming from? Japan! So Dark Horse formed a partnership with manga-ka Torajiro Kishi (best known for the yuri title Maka Maka) and anime producer Madhouse Studios (Ninja Scroll, Vampire Hunter D: Bloodlust). The fresh and original idea they came up with was a story about cops who hunt vampires … which admittedly sounds like every third comic published in the 1990s.

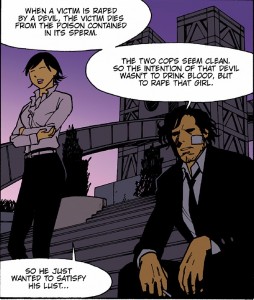

But there are two twists. The first is that the vampires are called devils, because in a post-Twilight world, “vampire” is no longer hardcore. The second twist illustrates why Japanese creators are always the smarter choice. I’ll let the main characters explain:

“When a victim is raped by a devil, the victim dies from the poison contained in its sperm.” And by die, they mean burst like a water balloon.

This is why Dark Horse needed Kishi and Madhouse Studios. Any American hack can write a story about cops who hunt vampires. They might even throw in some misogyny. But when it comes to uncensored depravity, American creators are actually quite timid. You need a Japanese creator to get a story about poison sperm that causes women to explode. It’s not any good, of course, but extraordinary sleaziness has a way of concealing every other flaw.

We Will Bury You #1 (of 4)

Publisher: IDW Publishing

Writer: Brea Grant with Zane Grant

Artist: Kyle Strahm

Colors: Zac Atkinson

Brea Grant plays the character Daphne on Heroes. That’s a red flag: when an actor starts slumming in the funny book industry that usually means they’re pitching a movie script disguised as a comic.

Though perhaps I’m being unfair to Grant, because I can’t imagine a major studio ever producing a film adaptation of this comic. The pitch: in 1927, a cross-dressing Ukrainian immigrant and her taxi dancer girlfriend are planning to flee New York after murdering the girlfriend’s husband, but they get caught up in a (Communist-themed) zombie apocalypse. Now that’s what I call high concept.

As this is only the first issue, it’s hard to say whether it will turn out to be a original zombie story. The zombie sub-genre has been thoroughly explored in every medium, and Grant is hardly the first writer to link zombie scares to the Red Scare. On the other hand, there’s never been a zombie story featuring flappers, and who doesn’t like flappers?

Plus, the comic has some engaging artwork.

Kyle Strahm’s style, with its distorted physiques and bleak backgrounds, is well-suited to horror. And the use of numerous thick lines gives his art a coarse, disheveled look. It effectively captures the grime and poverty of New York City tenements in the early 20th century. Zac Atkinson uses color to great effect too, as key characters are given more vibrant outfits so that they stand out from the darker backgrounds. More than a few panels, however, are rough around the edges in ways that Strahm probably didn’t intend. There’s a thin line between bleak and boring, and Strahm’s backgrounds occasionally step over it, and the facial features of the heroines seem to change on every other page.

Despite some misgivings, I liked the first issue of Brea Grant’s comic. It’s certainly better than her TV show.

State of the Genre

Overall, the horror genre is doing quite well. It has its share of shitty comics, but there are a few decent titles in the mix. And despite the dominance of superheroes in the Direct Market, horror comics have carved out a stable niche. There’s a broad selection of titles available in a variety of sub-genres (though zombies are far and away the most popular). It’s also worth mentioning that there are several genre hybrids that I passed over for reviewing, including Hellboy (horror/superheroes), Locke and Key (horror/fantasy) and the recently released Choker (horror/crime). On a less positive note, there’s an awful lot of licensed properties, but that’s hardly surprising given that an established brand with a built-in fanbase is always the safer bet. Fortunately, the horror genre hasn’t yet become an endless parade of Freddy v. Jason v. Chucky one-shots.