A couple of weeks ago I posted a series of discussions about the way in which super-hero comics tend to be structured around homosocial desire and the closet. You can read the whole series here.

Just to resummarize quickly: the basic argument is that a character like Superman is a male power fantasy. That fits in with Freud and the Oedipal conflict. Clark Kent can be seen as the “child” who imagines himself supplanting the Father/lawgiver/god. You can also take this one step away from Freud and argue (via the theories of Eve Sedgwick) that what we’re talking about here is not, or not solely, an internal psychological desire, but rather a cultural/social formulation. Men turn away from femininity in order to identify with patriarchal power; or, to see it another way, to be patriarchal requires the denigration or hiding of weakness. That’s the closet; Clark Kent is living a lie, pretending to be powerful in order to be powerful, when his truth is actually a weak, wimpy child. And, again, the closet is powered by male-male desires and fantasies, making it homoerotic (though, as I argue at some length, it’s actually a straight person’s homoerotic fantasy — we’re talking about how straight men bond or interact with the patriarchy in particular, and arguing that that interaction is structured by ideas about, and within, gayness.)

Okay, so that’s basically where we left things. In the last few posts, I was mostly interested in pointing out similarities in the way this basic blueprint was used across different kinds of comics, from Superman and Batman through Spider-Man and Hulk and on to the work of folks like Chris Ware and Dave Sim. But, of course, there are differences too from case to case, and it’s interesting to look at some of those, and how they work.

So first, I’ve been thinking a little about the differences between some of the early heroes of the 30s and 40s and the later iconic Marvel heroes. Generally, I think, the argument is that Marvel heroes were different because they were more realistic; they faced everyday problems, made mistakes and so forth.

I wonder how true that is exactly, though. The fact is, none of the Marvel characters are all that realistic. Peter has girl troubles, sure, and he gets bullied — but Clark Kent had girl troubles, and he got bullied too. And Peter’s a genius inventor. And he’s drawn to look like he’s 40 even though he’s only like — what? 16?

Anyway, the point is, I don’t think the change had all that much to do with verisimilitude. We’re still in the world of preposterous fantasy, after all, with cosmic rays and gamma rays and super strength and defeating your enemies by punching them in the face. The difference, it seems to me, has more to do with anxiety. The Oedipal split is always somewhat agonized and anxious; the superfather for Freud is also the super-castrating ogre. And in those early Superman stories, Clark is despised and castrated; there’s a definite feeling of loathing.

However, the loathing is in these directed mostly towards the castrated, not the castrator. The problem, the thing to be ridiculed, is powerlessness, not power.

Over time, though, the faith in that image of absolute power started to waver. In the 50s and 60s there was a lot of more-or-less playful experimentation with the idea of superman as evil father. Thus, the aptly (and Freudianly) named Superman is a Dick website.

Here’s a particularly apropos picture:

I don’t know that I can really add anything to that.

Of course, the stories here always resolved by showing that Superman was acting for everyone’s good; he may have looked like the evil father, but he’s still really the good father; patriarchy is still to be trusted, power is still great, and all the boys still want that super dick.

Marvel’s innovation was not that it gave us stories that were different in kind from Superman’s kid, Jimmy Olsen. Rather, the difference was that it was able to take exactly this story and treat it as tragedy rather than farce. The problems most Marvel super-heroes face is precisely that of the superdick. That is, they aren’t beset by normal, everyday problems — they’re beset by the Thing — the monster phallus itself. Peter Parker’s mega-problems (the death of his uncle in particular) stem from being Spider-Man; which is why, when he loses his powers, he’s acutely relieved. The early Marvel comics loved to portray super-powers as a crippling curse, a disaster. The Hulk is maybe the purest example; the uber-masculine ogre who hates and wants to destroy his weaker self. You couldn’t really come up with a more lurid Oedipal castration fantasy.

The Marvel stories, then, are about mistrust of patriarchal authority; they insistently question whether the great gay bargain — exchanging individual weakness for patriarchal strength at the cost of always hiding your weakness — is really worth it. In this, they’re not unlike exploitation films, which are from roughly the same time period and which were also obsessed, in various ways, with authority and changing ideas about masculinity and femininity.

But where exploitation films could, and did, revel in the perverse pleasures of fucking with authority, Marvel comics never (for various reasons) went there. As with Superman as Superdick, the stories always ultimately ended up affirming the worth of power as power. Peter Parker is relieved to lose his powers…but then his Aunt and girlfriend are captured, and he realizes how much he Needs to Be a Man and grasp the superdick in order to save them. And even though he’s an ogre, The Hulk, somehow, always ends up being a force for good (and eventually became childlike himself, neatly undercutting the evil-ogre-father aspect of the character, which was much more prominent in the first issues.) Moreover, Stan was hardly above indulging in some Superman style superdickery himself; Professor X and other father figures are always running the X-Men through this or that idiotic test for their own good. “Yes, my X-Men, I gutted Ice Man and used his bloody remains to lubricate the gears of my Cerebro computer, then let you think he was dead for weeks. But! The experience has made you stronger as a team! And Cerebro is working really well now! And besides, before I brutally murdered him, I created a perfect robot duplicate, whose powers work better and who doesn’t engage in annoying pranks. Say hello to you new teammate: Ice-Bot!”

Having just written that super-hero parody, I have to say…it’s interesting how much super-hero parody revolves around superdickery. Chris Ware’s Superman, for example, is essentially a brutal sadist destroying everyone who contradicts him; Johnny Ryan has a superman/god character who works in a similar way. And then there’s Kate Beaton’s bad-ass Wonder Woman. And a lot of the humor in Mini-Marvels is based on the kid heroes behaving like megaomaniacal uber-fathers (Reed Richards cheerfully sending the Hulk off into space for example.) And, of course, that’s the whole point of Marvel Zombies too, with the heroes turned into evil ogres and at last wholeheartedly embracing their inner superdickery.

In fact, the genius of the early Marvel comics is not that they undercut (as it were) the superdick, but rather that they reconsecrate it by more fully acknowledging its dickishness. Males (and especially adolescent males, the ones reading these comics) are always ambivalent about sadism and patriarchal power, both because the sadism and patriarchal power is likely as not to be directed against them (“go to your room!” go off to war!”) and because, you know, who wants to be always about to become the ogre raping and murdering their own loved ones? That very guilt and fear, however, function as a lever and a spur. Peter Parker kills his father….and his life is thereafter defined by the guilt that demands he himself become a monster/father to take Uncle Ben’s place. The Hulk, in his later incarnations, is not just the destructive phallus, but the wounded child as destructive phallus; the fantasy, both terrifying and fascinating, is to become the ogre-father while still an infant, eternally both torturing oneself and satisfyingly wreaking instant vengeance, on oneself and others, for the torture. Marvel figured out that you don’t need to deny the anxiety and guilt attendant upon the power fantasy; rather, you can harness them to make the green monster grow.

So a couple more comments about this.

— I think that, as others have pointed out, power fantasies (or superdickery) is really central to the super-hero genre. And I think that what that means in part is that the super-hero genre is — not always, or everywhere, but quite centrally nonetheless — sadistic. It’s about identifying with power — either for good, or for ill. It’s about being the beneficent god or the evil ogre father, or both at once. To the extent that you do identify with weakness, it’s generally as a prelude to releasing your inner hulk, or going out to websling, or whatever.

—This is a big part of why superheroics and horror (as opposed to goth) don’t mix especially well. You can certainly have gore in something like Blackest Night, because gore and violence fit perfectly well with sadism; you can be the ravening ogre father chomping on bones, hooray! And, yes, sadism does have a place in horror too — thus torture-porn — and to that extent it does make some sense to think of Blackest Night or Marvel Zombies as some kind of horror crossover. But the central mode of horror really is not sadism; it’s masochism. It’s about being the devoured child, not the devouring father — in horror, while you may cheer for the ogre at various points, you never actually are the ogre; you’re the victim, which is where the fear comes from. The whole point of Shivers or the Thing or the Living Dead movies is that the characters are consumed; they are destroyed, and then eaten up or filled up by the Other (which is pretty explicitly the phallus, in Shivers and the Thing, especially.)

But super-hero comics never do that; even when the super-heroes are evil, they have a recognizable personality, and are the stars with which you (more or less) identify. The two genres, super-heroes and horror, are simply diametrically opposed; they are committed to opposite goals. Super-hero comics are fun because they empower; horror is fun because it disempowers. You can’t do both at once. (Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing is an exception that tests the rule, perhaps…I found the Swamp Thing vampire story at least fairly scary. But Moore accomplished that by keeping Swamp Thing himself off screen for most of the story while various civilians are terrorized and slaughtered. When Swamp Thing did show up to do battle with a giant frog/lizard/vampire thing, the horror quickly dissipated.)

—Masochism is central to the way that exploitation films, such as horror, express their distrust of the status quo. Not that horror films are actually revolutionary, per se, or that I Spit on Your Grave is going to overthrow the patriarchy or anything. But, effectual or not, a film like Last House on the Left really expresses a visceral distaste for patriarchal authority. It sneers at good dads and bad dads alike, and at the war they perpetrated, and at the whole concept of justice and truth. And again, it does this through masochism — through identifying with victims and getting pleasure/excitement/terror through fantasies of disempowerment rather than through fantasies of empowerment.

Super-hero comics on the other hand, have a lot of trouble making that kind of perverse identification with the disempowered. This is the case even with parodies like Marvel Zombies or Ted Rall’s Fantabulaman or even Chris Ware’s Superman/Jimmy Corrigan strips, where there’s generally a kind of contempt for Jimmy’s weakness which echoes the distaste for Clark Kent or Peter Parker. In all these parodies, the focus is largely on the evil father doing the ogrish evil; the victims are much less personified or even visualized. Even if you have your tongue in your cheek while admiring the superdick, you’re still kind of admiring the superdick.

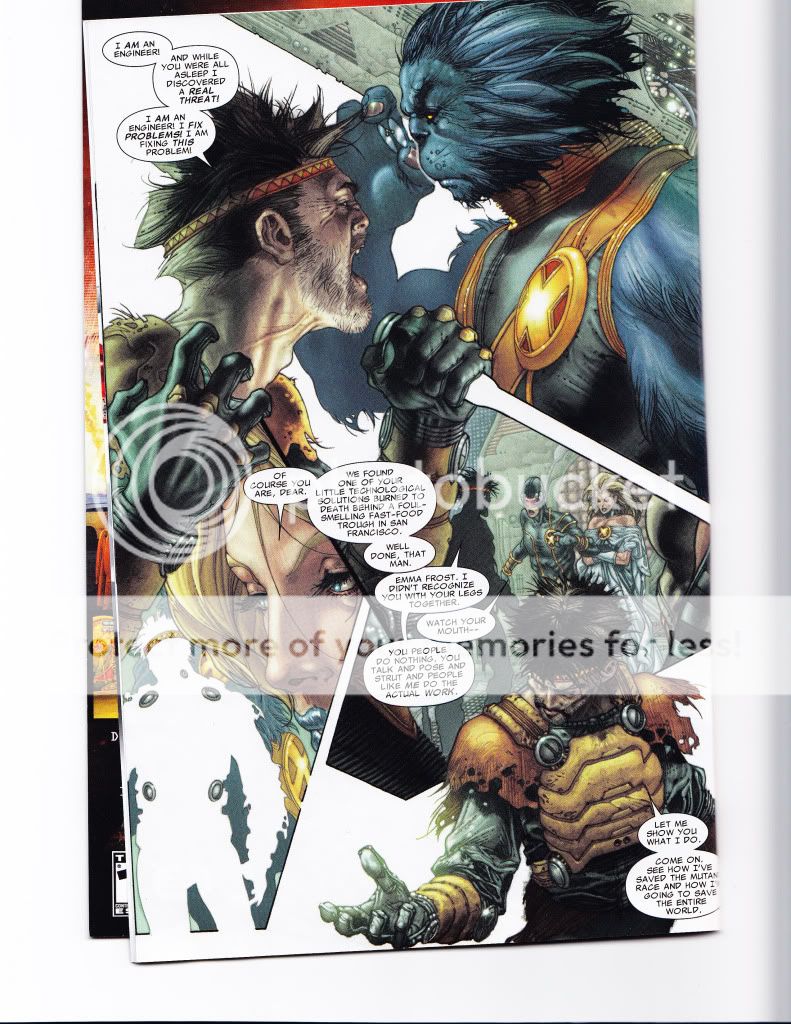

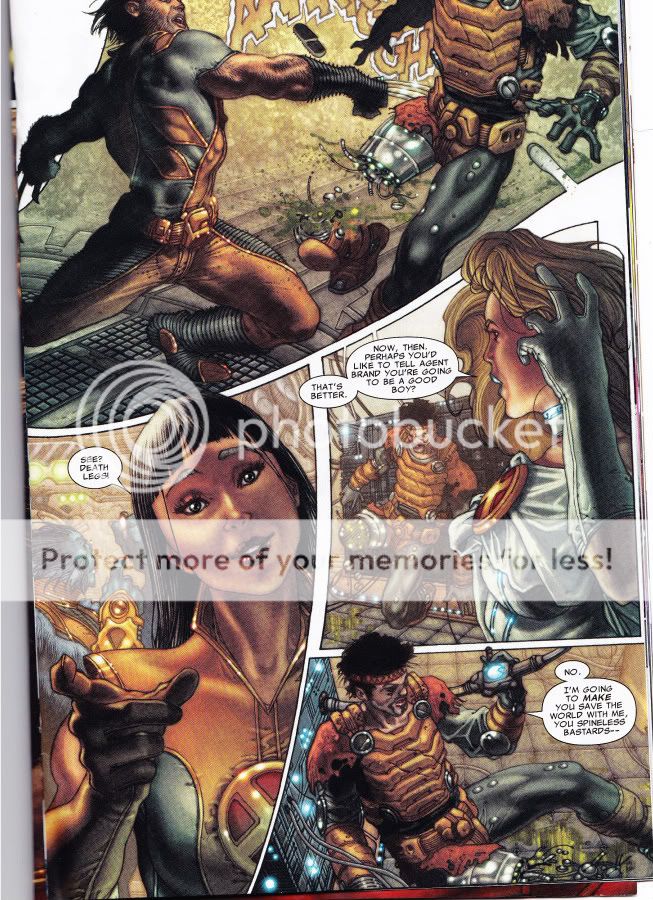

Grant Morrison’s mainstream work provides an even clearer example. In his Justice League and X-Men runs, he often has his villains launch fairly damning critiques of the heroes as egotistical, self-satisfied, godlike assholes. But then he always kind of takes it back; the heroes waltz on and show that they’re noble and good and they save the world and you’re supposed to be all enthusiastic, I guess. Obviously, Morrison identifies with the critique to some extent, but there isn’t any way in a super-hero comic to let it have the last word, or to have it be the point (as it is, to some extent at least, in the Invisibles.)

Another example is Greg Rucka’s Hiketeia. Rucka puts a certain amount of effort into making the story masochistic. The cover features Wonder Woman stepping on Batman’s head, and the plot is a rape-revenge, in which a young girl slaughters her sister’s killers, taking the knife to patriarchal notions of justice and fairness. Men get beat down by storng women. However…in the first place, this is a Wonder Woman comic, and a lot of the emotional oomph comes from watching her beat the tar out of Batman — you identify with her, which is sadistic rather than masochistic. Secondly, the story ends up being not about the girl and her revenge at all, but instead about the tragic rift that the girl’s rape-revenge creates between Wonder Woman and Batman; a rift the girl, rather inexplicably, sacrifices herself to heal. It’s like she hears all the genre rules yelling at her that she’s supposed to be the one getting castrated, not doing the castrating, and she finally acquiesces — perhaps just because she can’t stand being written by Greg Rucka any longer.

Again, Watchmen is perhaps an exception of sorts here, where the role of all-powerful father is both questioned and in various ways deflated. But it took Moore a number of false starts before he got there (Miracleman and V for Vendetta try to mount an anti-establishment critique via super-hero, but ultimately, I’d argue, end up defeated by the genre conventions.)

The point here isn’t that stories supporting status quo are necessarily bad. Dark Knight is pretty unabashed in its worship of the superdick, and it’s great. And, as the Dark Knight kind of suggests, the status quo has numerous benefits (stable currency and revolutionaries not stringing up me and mine from flagpoles = good.) It is interesting, though, the extent to which the superhero genre’s bias towards and fascination with the superdick makes it difficult for authors to tell certain kinds of stories (horror, anti-status-quo) even when they’re clearly trying to do so.

_______________________

Well, that was about twice as long as I thought it would be. I still want to discuss the question of whether Wonder Woman can be the superdick…but I think we’ll have to leave that for another day.