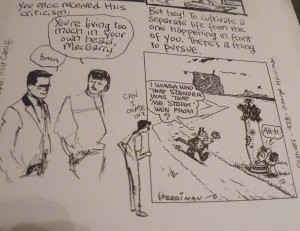

So for a change I thought I’d highlight one of my own comments from way back when. This is in response to a piece by Caroline Small talking about the prose in Eddie Campbell’s Alec. Here’s what I said:

Ack! I’m reading along and grooving on Caro tossing around comics and space and time and then I get this [passage by Eddie Campbell] as an example of stellar prose:

“But hey! to cultivate a separate life from the one happening in front of you. There’s a thing to pursue. An inside life, where Fate talks to you, sometimes in the charming tones of a girl singer with old Jazz bands.

Othertimes in a naive wee voice in which all things are still possible.”And I just want to bang my head against the wall.

I just…to me that’s such romanticized, sub-Beat, stentorian self-dramatizing bosh. If I never, ever, hear anyone reference girl singers in Jazz bands as some sort of ne plus ultra of authentic wonderfulness again, then I will have died only hearing it about fifty billion times too many. And “a naive wee voice in which all things are still possible.” Fucking gag me.

Really, I have a visceral loathing of that passage. It’s slam poetry crap.

And part of what I hate about it is exactly the time slips that Caro describes. Maybe I suffered too much damage from my youthful immersion in contemporary poetry, I dunno…but so many, many ungodly contemporary poems (and maybe not just contemporary, but…) end in this lyrical future tense. And it’s supposed to do exactly what Caro says here:

“This is the “potentiality of being” specific to the artistic mindset: “to cultivate a separate life from the one happening in front of you.” That describes an ecstasy of art, and part of the brilliance of this book is the recognition of that ecstatic potential in the mundane life story.”

The world is cut off from the world and made poetic; the mundane is made lyrical. Or, alternately, you could say that the world is picked up and dumped in the poetry machine and then you turn the crank. And out comes ecstasy, hoorah.

I don’t think there is an artistic mindset. I don’t think there should be. I don’t think artists are priests, who make the world ecstatic through their transcendent quiet inwardness; who cast a glamour on the earth through their numbing recitation of important aesthetic touchstones (girl singers! Krazy Kat!)

I think this quote points to what made this book so unpleasurable for me:

“Solipsism is alluring, but impossible. Art comes from other people, and other art, and from experiences in the world. ”

The thing that interferes with solipsism is that it doesn’t fit with art. You start with the need for art, and that leads you to realize that the world has to be there too. But the problem is…for me, in this book, the world is *always* there for the art. The experiences are all there to be chucked into the poetry machine. That’s what happens to his wife and his baby; new fatherhood gets transmuted into standard-issue poetry tropes. That’s what it’s there for. Which I find both, yes, solipsistic, and also really depressing.

Obviously that’s not what others are getting from this, and

I appreciate that, and I think this essay is lovely, but…man, it makes me like the book even less, not more.___________

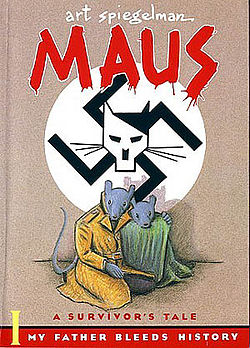

And just because this comment isn’t long enough…and I want to say something positive….I think the discussion of prose is really interesting…but I think that you’re kind of missing out on what Charles Schulz is doing if you’re arguing that he’s using condensed meaning in images as a substitute for prose. I think Peanuts is probably as prose the best-written comic, period — certainly better written than Alec, to my mind, though not as wordy obviously. Better written than Delillo too, by a long shot. Schulz had a really idiosyncratic ear for language and a love for words. Some of his strips are sight gags, but a lot of them would pretty much work without the pictures; they’re about puns and verbal dead ends and misunderstandings and different registers of language. He’s usually thought of as a minimalist because of the drawings obviously; but thinking about your essay, you could also see the sparseness of the drawings as a way to give room for the language; as you say, the drawings become a kind of rhythmic device rather than a meaning making one.