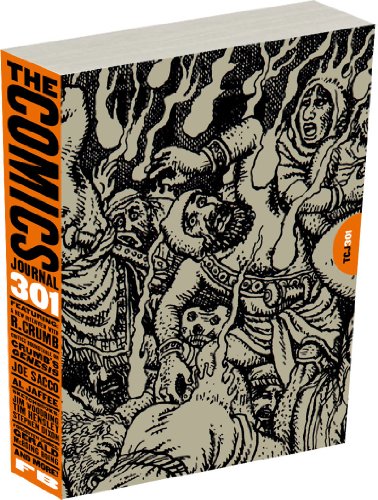

Robert Boyd an editor of The Comics Journal, wrote in HU comments about why TCJ was so anti-superhero while he was there.

I was at TCJ in the early 90s and I guess I represented the POV that you speak of as well as anyone. I loathed mainstream comics. I made serious efforts to read the ones people said were good, like Animal Man, and found them terrible. For the most part, I still hate mainstream superhero comics. Gary can answer why he thought about them they way he did, but I think a lot of it was political–they were assembly line product produced by uncaring corporations. But my main complaint was that they weren’t interesting to me. (Obviously I could go deeper than this, but my interest level isn’t all that high…)

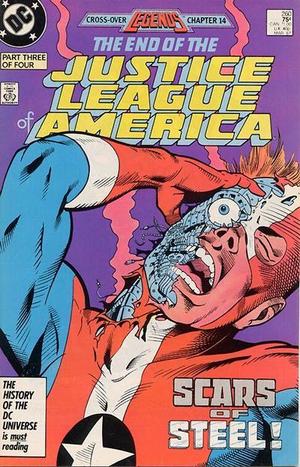

But here’s one thing that you have to remember–just how freaking dominant superhero comics were–in sales, of course, but also in visibility. Going to a comic convention was painful–and the certainly was nothing like SPX or TCAF back then. Wizard celebrated the worst artistic values imaginable and was he single largest comics publication (it outsold the comics it covered!) there was a general feeling in the office that they had their media, their conventions, their movies, their stores, etc. TCJ would be for “us”–and it felt like it was the only thing for us.

As someone interested in non-superhero comics, I feel like there is an infrastructure that I can tap into to enhance my enjoyment of these books. I can easily read reviews of just about any comic I want to. I can go to the Brooklyn Comix & Graphics Festival., etc. but in the early 90s, TCJ was my life raft. (one that amazingly helped pay my salary.)

I think this context is important.

And here’s a second lengthy comment.

If a reader didn’t like the editorial position of the Journal, I can understand. After all, magazines can’t be all things to all people. But the accusation of forming a clique seems silly. Let’s say the Comics Journal did cover superhero comics in the early 90s in a more inclusive way. Could you then say that it was ignoring newspaper strips. And if it included newspaper strips, couldn’t it be blames for not covering Japanese and European and Latin American comics more closely? And if it covered them, how can you excuse it for not covering other art forms–instead of just catering to the comics clique. In short, a magazine has to have some kind of focus. Non-mainstream comics was our focus.

Instead of clique, consider the words “constituency” or “market segment.” Magazines have an idea of their ideal reader, and this ideal reader evolves over time. Under editors Greg Baisden, Helena Harvilicz and Frank Young, that ideal reader was someone who had little interest in (and even antipathy for) superheroes. It was someone who liked the comics that were bubbling up from below, from the Xerox machines of the nation (which is why I started my column “Minimalism”). It was a reader who was looking for a new history of comics that was a counter to the then prevailing superhero-centric notion of comics history = “Golden Age” to “Silver Age” to “Bronze Age”. We weren’t totally consistent, and the hostility expressed towards Superhero comics was over-the-top, but since hardly anyone was paying attention to the kinds of comics we LOVED, we felt justified in making them our near-exclusive focus. If in doing so, we were shutting out the super-hero fans, so what–99% of the comics industry was devoted to catering to their tastes already. They had loudly and repeatedly proclaimed they didn’t need the Journal–or alternative comics.

Indeed, the basic feeling of the entire American industry at the time–the shops, the conventions, the distributors, the fan magazines, and most of the fans themselves–was a desire to see us (the people who read and produced and wrote about alternative comics) just go away. Larry Reid had a word for the comics stores that supported us–”The Fantagraphics 50.” Our existence as a publisher and the existence of the comics we liked was utterly precarious and dependent on the Direct Markets stores that for the most part loathed anything remotely alternative(there was no bookstore distribution at that time, really).

There are two ways to deal with that kind of environment. One is the MLK integrationist approach, and the other is the Malcolm X separatist approach. For a relatively few years (the time I was there before Spurge joined up), we went the Malcolm X route. It may have been a mistake, but our feeling was that we didn’t want to join a club full of people who hated our guts.

And in our clumsy way, we published a magazine for people who felt utterly alienated from the mainstream-superhero world. I can’t speak for everyone involved in the Journal at the time, but I think it was a necessary move. We had to build up this alternative art history of comics and stake a claim for all the cartoonists working outside the ridiculous conventions of the mainstream. It lead us into a somewhat extreme position (temporarily, I’d argue), but it helped give space for a lot of non-mainstream talents to develop and receive attention.

The original post by Robert Stanley Martin is here. Robert Boyd’s website is here.