The United States has a war canon. That’s a pretty uncontroversial statement. We can even populate this canon in a trivial way by just listing off war movies. American Sniper. Eye in the Sky. Zero Dark Thirty. The Green Zone. Saving Private Ryan. And the list goes on, with movies as well as written work from Tom Clancy to James Fenimore Cooper.

But there is not a whole lot of room in that canon for movies that make the audience really uncomfortable with war. Eye in the Sky is a major exception, but even that movie depicts war as the moral backdrop against which brave soldiers prove their dedication by making the difficult, but necessary decision to risk murdering a child. You know, to keep us safe

.

Regardless, these movies, and many more, all depict war as the backdrop against which mere mortals become heroes. Almost always, they do this by demonstrating their masculine willingness to kill civilians (American Sniper, Eye in the Sky), or by demonstrating their masculine willingness to torture (Zero Dark Thirty). The Green Zone presents an exception in that Matt Damon spends the film invalidating the justification for going to war in Iraq. But it is still a story about a white guy demonstrating his heroism with the Middle East as the backdrop for his journey.

The American war canon is, therefore, largely designed to whet the audience’s appetite for war, as a system and an action. So what if you were to construct a war canon that dulled the audience’s war appetite, a war canon antithetical to the one we are saddled with now? Setting aside the fact that such war canons already exist in other nations, where would we start if we wanted to construct a new one?

I argue that the manga/anime (I discuss the anime) Attack on Titan, the comic Saga, and the webcomic Gone with the Blastwave form a solid base from which to start. Of the three, Attack on Titan is the most comprehensive and forcefully crafted, but all three depict war as a hellish landscape (metaphorically and literally) from which you escape only if you are lucky, whether you are a civilian or a combatant.

________

The anime, Attack on Titan, provides an excellent position from which to start, as it directly confronts the subjects of trauma and class during wartime, and presents a direct challenge to the American notion of heroism in war. When substantiated by, and viewed in tandem with, Saga and Gone with the Blastwave, Attack on Titan forms the solid base for a new war canon that acknowledges war as a hellish landscape from which combatants and civilians alike escape only of they are lucky.

The most stark and obvious of the three is Gone with the Blastwave, which depicts a handful of soldiers navigating their way through a city that is so drenched in radioactive fallout that the soldiers only survive because they wear full-body protective gear and gas masks that obscure any identifying features. The only way to tell them apart as they traverse a gray, rubble-covered, otherwise featureless landscape is by tiny emblems on their helmets. In this way, the environment literally created and mirrored by war itself dehumanizes those involved, stripping them of their identities and forcing them to some disgusting lows to survive.

GWTB doesn’t even ennoble this struggle for survival with a reason for the war’s perpetuation. The faceless soldiers fight a meaningless conflict against equally faceless enemies, themselves having no ideology or allegiance accept to fight and to escape. Saga achieves the same fatalistic effect by relegating the origins of a galaxy-encompassing conflict to long-lost historical memory. The war goes on because those people over there shot me, so fuck them.

In this way, Saga’s depiction is equally bleak, despite its forcefully colorful artwork. The rationale for the persistence of this galaxy-spanning war is that it has always happened. An interplanetary system of violence naturally reproduces itself through hatred and trauma, and so the only response the average citizen can muster to the question, “Why do we fight?” is, “To win the war,” followed by a fatalistic shrug, “Meh…works for me.”

The conflict rages on, because fuck the enemy.

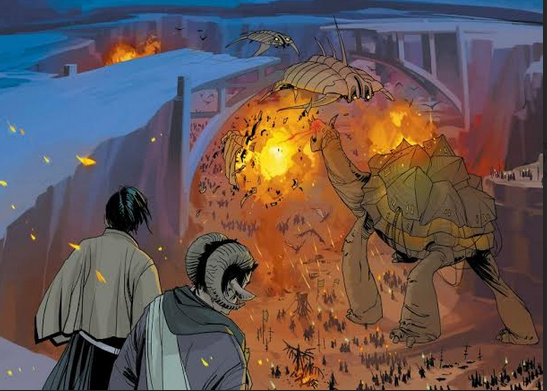

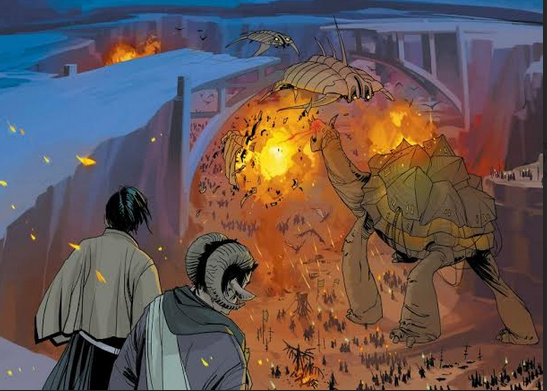

Of course, the central conceit at the heart of Saga is that two new parents from opposite sides of the conflict fall in love, and resolve to raise their child away from the war. The panel above represents the war as a literal barrier to parenthood, blocking the nascent parents’ path to safety, where they can raise their child. The whole thrust of the series is these parents, Alana and Marko, trying to escape the war, literally and figuratively, for the sake of their child. When they eventually find a safe place to settle down, away from combat, they are then faced with the demons they brought back with them. Alana is driven to narcotics in order to endure her trauma and the soul-crushing nature of the work she takes to make a living. Marko is haunted by the specter of his own history of violence, on and off the battlefield. In both cases, the parents are chased from the battlefield by demons that repeatedly threaten to endanger their family, as bodies and as a community. As their favorite author, Oswald Heist, notes in a kind and sagely voice, “In the end, nobody really escapes this thing.”

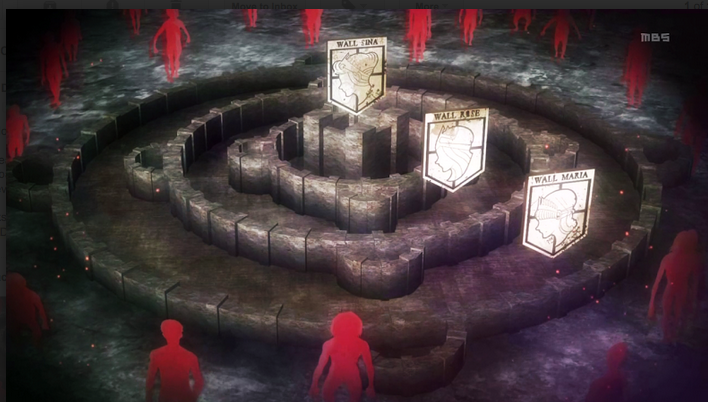

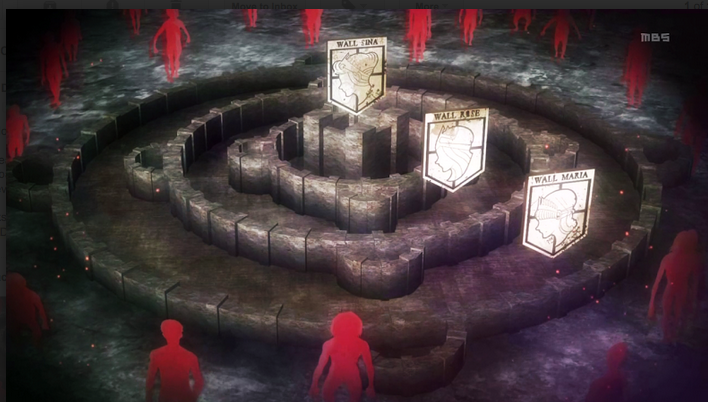

This truism makes Attack on Titan especially tragic, as the main character, Eren Jaeger, hinges his entire motivation on his desire for freedom. Eren lives in a society that is hemmed in by huge, 50-meter walls, which serve to protect the last vestiges of humanity from the Titans, bloodthirsty, man-eating giants. The Titans devour and crush humans, creating a literal embodiment for the way in which war figuratively devours and crushes humans. Eren becomes a soldier in order to slaughter the Titans and bring an end to the fear and captivity of living behind walls. He learns to use “omni-directional mobility gear,” designed with a grappling hook-and-gas power mechanism to allow humans to swing around vertical environments like Spiderman, enabling them to fight the Titans with some success. By any measure, these soldiers learn to move and fight in ways that are nigh superhuman. In the lead-up to Eren Jaeger’s first battle with the Titans, he and his fellow cadets talk trash to each other and boast about how they will beat the Titans back with ease. The bravado is so intoxicating that it is a genuine shock when Eren and his fellow cadets are almost immediately decimated by the Titans, eaten alive in a matter of minutes.

This turns out to be merely the beginning of the carnival funhouse of horrors that is the Battle of Trost District. A young woman tries to revive her clearly deceased sweetheart in the middle of an empty street. A central character wears a look of visceral shock as he stumbles around the city after watching his friends get eaten alive. A group of cadets cowers inside a building as the Titans roam outside, staring into the windows, while one calmly cleans a rifle and blows out the back of his head in front of them. And amidst all of this, vital officers and support personnel all lose the will to fight, leaving the majority of the cadets out in the cold against their monstrous adversaries. Where the arc starts with vibrant colors and blue skies, the main body of the arc paints the scenery in dull, muted grays, as the once cocky and macho cadets wear looks of fatalistic resignation. In short, this is not an environment that breeds heroes. It devours them whole.

So when one of the cadets, Jean Kirschtein, takes the lead, he makes ruthless decisions that prioritize the survival of the majority over heroism and nobility. As he watches a comrade get caught and eaten by Titans, he freezes in place, and when two more of his comrades heroically enter the fray to save the very same comrade, they get caught too. Jean can do nothing but watch his friends get devoured as he grows roots in a high place away from the Titans’ reach. That is, until he takes command and orders the remaining cadets to use the Titan feeding frenzy as a distraction in order to grapple past them to safety.

What follows is a high-octane, pell-mell sprint to safety through a mass of Titans that continue to swat and chomp Jean’s comrades, and he uses every death as an added distraction to aid his own flight and the flight of his remaining friends. Upon landing in a safe place, he kneels in shock and asks himself, “How many friend’s deaths did I use?” We never get an answer, but we do witness a later conversation between Jean and Marco Bodt, a talented and friendly comrade, who praises Jean’s ruthless decision. When Jean castigates himself for weakness, Marco says that he thinks the fact that Jean is not strong helps him appreciate how the weak feel in battle. Marco goes on to say that it is this “weakness” which led Jean to a decision that kept Marco, and many others, alive. The sweet, sensible, and affable Marco tells Jean that his outwardly ruthless and cowardly decision was actually the compassionate and brave response needed to save his friends.

But the escape that Jean engineered is only temporary and superficial. When the battle ends and the cadets are no longer in danger of outright death, they have to deal with the trauma of combat. A particularly illustrative scene shows Jean aiding in the triage and cleanup after the battle, and finding Marco’s body, cleaved in half as if by a giant maw, laid down in an isolated corner of the battlefield. Jean is visibly shaken and worn by the realization that the friend who praised his leadership and character suffered a lonely death at the hands of a monster, with no friends to aid him, or even witness his demise. It is a brutal and blunt reminder of the lingering effects of war.

However, the war lingers much further beyond the battlefield than the triage tent. Attack on Titan extensively demonstrates the effect the war against the Titans has on society, namely the class stratification aided and abetted by the military hierarchy. One scene has a member of the landed gentry, living near the center of human territory, far away from the danger of the Titans, attempting to brow-beat a high-ranking commander, Dot Pixys, into abandoning the perimeter towns to the Titans, instead pulling his forces back to protect the noble’s lands. While this effort fails, the landed gentry, the clergy, and the merchant class nonetheless form a powerful block that clearly benefits from a stratified society, with wealth clustering in the center of human territory, and the poor scattered about the fringes. This structure is aided by the military, which depends heavily on the patronage of the merchant class for its supplies and food. Moreover, military politics threaten to squander multiple strategic opportunities to fight back against the Titans, with the military police serving the interests of the merchants and the nobility by suggesting conservative strategies, which prioritize the wealth of that class. In the midst of all this, the military is the only way for the poor to access a comfortable life in the interior, with upward mobility by other means relegated to the dustbin of utopianism.

Guess where all the rich people live.

Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples depict essentially the same scenario in Saga, except it is less symbolic and more concrete. Vaughan’s narrator, Hazel, goes on a lengthy aside to discuss the society in which her mother grew up, saying about military recruits, “Many of those who answered this call [for military service] did so out of a genuine sense of duty. Others were merely looking for adventure. Some were trying to escape a bad situation. Almost all of them were poor as shit.” When a poor man named Dengo kidnaps a royal heir of the Robot Kingdom, an ally of one of the warring sides, an intelligence operative tells the Prince that is the heir’s father, “If you’re lucky, he’s hiding. If you’re not, he’s trying to start a revolution. And trust me, that’s the last thing you poor bastards want. The whole point of having enemies abroad is getting to ignore the ones back home.” In these cases, and in Attack on Titan, constant warfare plays cover for class stratification, and the military serves to weaponize the poor against a foreign enemy in the interests of the political class and the wealthy.

Which brings us back to the original point of this piece, that being why these three works could form a fruitful basis for a new American war canon (in spite of the fact that two of the three works were not originally made by Americans). Saga and Attack on Titan both depict societies dominated and consumed by warfare, and GWTB mirrors this by crafting war into a literal, toxic environment against which the protagonists set themselves. In all three cases, the protagonists’ main concern and goal is survival, in the short and long term, actions can be judged as heroic only against that goal. In other words, all three works depict their protagonists struggling concretely and in the abstract against a totalizing militaristic system that presents itself as the main obstacle to their own safety and happiness. As Eren notes in a conversation with Dot Pixys, humankind has a common enemy in the Titans, and yet they still squabble over property and class. Ozymandias’ alien tentacle monster has descended from the sky, and humankind has decided to carry on as usual.

In all three works, participation in the war machine is a Pyrrhic venture at best, and a Sisyphean one at worst. In all three, the protagonists struggle against the totalizing militaristic system in which they live, as much as they do against, “the enemy”. Most importantly, in stark opposition to the predominant American war canon, all three aggressively ask the question, “Why do we fight?” and force the audience to acknowledge the unsettling, blindingly obvious answer, “I don’t know.”