I was just reading Amazon reviews for a collection of essays by philosophers on the topic of comics, and one disgruntled reader complained that the authors “spend most of their time simply trying to define precisely what comics are,” which felt to him like an “elitist” attempt “to justify the fact that one is writing an academic work on comics in the first place.”

Actually, analytical philosophers spend most of their time simply trying to define precisely what everything is. That’s where philosophy and genre theory happily collide. For me the collision took place in front of my English department’s photocopier. Nathaniel Goldberg had descended from the Philosophy floor because their machine was dead. A year later and he and I have drafted a book on superhero comics and philosophy together. In the process I learned what is now one of my favorite phrases, “necessary and sufficient,” as in “What are the necessary and sufficient qualities for something to be a comic?”

It sounds like an easy question. The above mentioned disgruntled reviewer answered in one sentence: “I think most people who are passionate about comics would define the medium (not to draw an exact equivalency) much like Justice Potter Steward defined pornography: They know a comic when they see it.”

Actually, defining porn is damn near impossible. What precisely is the difference between a Playgirl centerfold and Michelangelo’s David? They’re both representations of gorgeous naked guys. My friend Chris Matthews has a great story about bumbling into a Robert Mapplethorpe exhibition with his father back in 80s. Which is to say, context seems to matter. The U.S. courts spent a lot of time changing their minds about the words “lust” and “obscene” and “importance” and “value” and how much of each is and isn’t enough to be or not be pornographic.

Comics should be easy in comparison. Except scholars keep changing their minds about the words “narrative” and “sequence” and “image” and “art” and, well, “words.” One-panel comic strips like Gary Larson’s The Far Side or Bill Keane’s The Family Circus present a particular brain teaser. Most definitions include something about pictures working in relation to each other, which means there’s got to be more than one picture. But then there’s The Family Circus right in the middle of the newspaper comics page, so it’s a comic in the seeing is knowing sense.

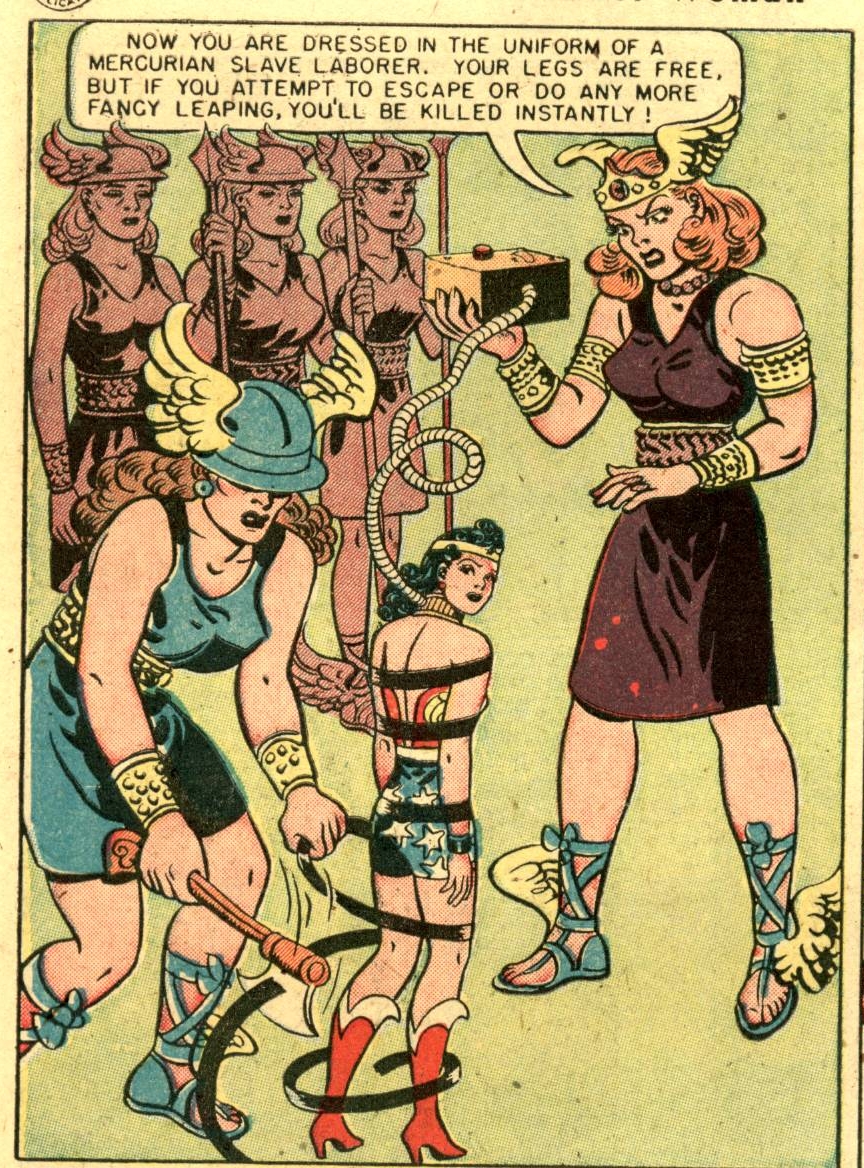

So maybe then it’s the combination of words and pictures? Philosopher David Carrier even includes word balloons in his “necessary and sufficient” list. So then Larson and Keane made comics because their cartoons include both an image and a caption–which, okay, a caption isn’t a word balloon, but close enough. Either way, the definition opens an unexpectedly large door. What precisely is the difference between a one-panel comic strip and, say, René Magritte’s The Treachery of Images?

Magritte is even making a joke, so it’s a comic in the “funny papers” sense too. And what about a one-panel comic that doesn’t have any words?

Dietrich Grünewald would call that Far Side an “autonomously narrative picture” because the single image prompts viewers to “create further images in our minds,” images he calls “ideal” or “non-material sequences.” So in that sense a single image can be multiple. But then comics suddenly include a massive array of representational paintings. What further images does Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp create in your mind?

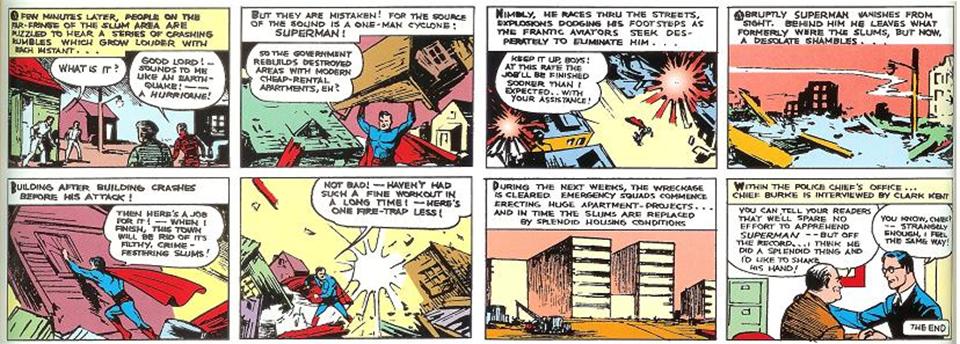

And what about moving pictures? Why aren’t films comics? They’re art made of images viewed in sequence to create narratives. Silent ones even have word captions. Some animated films include not just any pictures, but the same specific pictures that appear in related comic books. Like those God awful Marvel cartoons from the 60s, those are the same Jack Kirby drawings on the screen as on the page. And yet seeing any animated film is knowing it’s not a comic book.

Roy T. Cook offered a definition last year that separates comics from films by adding: “The audience is able to control the pace at which they look at each of the parts.” I also control that pace I wander through an art gallery, so are exhibitions a comic book? Framed painting are a lot like panels, and how is the white wall visible between them not a gutter? Greg Hayman and Henry John Pratt define a comic as “as a sequence of discrete, juxtaposed pictures that comprise a narrative, either in their own right or when combined with text.” Plus “the visual images are distinct (paradigmatically side-by-side), and laid out in a way such that they could conceivably be seen all at once. Between each pictorial image is a perceptible space.” Thierry Groensteen agrees, since according to him a comic contains “always a space that has been divided up, compartmentalized, a collection of juxtaposed frames.”

Great, but have you ever seen an episode of 24? When my TV screen divides into four frames, does the show become a comic book? Even some seeing-is-knowing comic books aren’t comic books by those definitions. John Byrne’s Marvel Fanfare #29 (Marvel, 1986) is all splash pages, no compartmentalized panels, no gutters. Though maybe that’s why Marvel rejected it for The Incredible Hulk #320? Emma Rios’ 2014 Pretty Deadly includes at least one page with overlapping images that are not “discreet” or “distinct” and include no gutters, and even the sense of sequential order is questionable.

I like the term “graphic narratives” because it combines graphic novels and graphic memoirs into one category, but it’s got problems too. Like Hayman and Pratt, David Kunzle, Robert Harvey, and David Carrier all rely on “story” or “narrative” to unify what they call a “sequence,” but as Andrei Molotui shows with his 2007 collection Abstract Comics, comics don’t always tell stories. The images just have to relate in some way. That means any diptych, wordless or not, representational or not, might be a comic. So anything from Piero della Francesca’s Portraits of the Duke and Duchess of Urbino to Roy Litchenstein’s WHAM! to Mark Yearwood’s Natural Ambiance Diptych.

Roy T. Cook challenges even the assumption that comics need to contain pictures–though his example of “a completely blank issue of a previously established series” would be a comic book only because the issues before it were. Context really is everything.

The bigger challenges are not thought experiments though, but works of art that already exist. Scott McCloud criticizes Will Eisner’s term “sequential art” for not separating comics from other art forms that might also be called sequential art, and Aaron Meskin in turn criticizes McCloud’s definition—“juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or produce an aesthetic response in the viewer”—for the same reason.

Meskin also objects to the anachronistic use of “comics” to include artworks, such as the 9th century Bayeaux Tapestry, that predate the term. But by that logic, Jules Verne and H.G. Wells are not science fiction authors because “science fiction” was coined in 1929. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “chiaroscuro” dates to 1686, after the deaths of its exemplary artists, Rembrandt and Caravaggio, and the technique is commonly traced to Ancient Greece. Anachronistic terminology is a norm of categorization and analysis.

If comics are the art form of juxtaposed images, then a great many artworks not typically considered comics retroactively join the club–including the Bayeaux Tapestry, Matisse’s Jazz, the engraved poetry of William Blake, and the word and photography-combining art of Barbara Kruger. Lots of road signs and magazine ads creep in too–unless we limit the category to “art,” whatever that may be.

My course “Superhero Comics” makes my job a lot easier since that subgenre squats squarely in the middle of the definitional zone. My reading list includes only comic books–a term that used to mean a collection of reprinted newspaper comic strips. I know of no single-panel superhero comic strips, so Larson, Keane, Magritte, and Rembrandt are irrelevant. And superhero graphic novels all tell stories (though I asked my library to order a copy of Abstract Comics just because it’s really cool). Plus they’re filled with panels and gutters and word balloons, so every one of the above definitions applies.

But things get trickier the further you stray from Action Comics No. 1.