This is part of a series of essays written for Chris Gavaler’s comics class.

What happened to Peter Parker’s real parents? Most people cannot answer that question, and many have never even considered it. But anyone with a basic understanding of comics knows that Parker’s real parental guidance comes from his aunt May and uncle Ben. Because of Ben and May, Peter goes from a nerd given superpowers to a real superhero. Similarly, it is an event related to Bruce Wayne’s parents that transforms Bruce into Batman; if Mr. and Mrs. Wayne survived the gunshots outside of the cinema, Bruce would just be the next wealthy leader of Wayne Enterprises. Meanwhile, in a more modern comic, Ms. Marvel: No Normal, we can see that Kamala Kahn’s parent’s overbearing control actually sets her free and enables her to become a superhero because of her initial need to rebel.

Comics, much like Disney movies, have a tendency to eliminate parents early and to portray them as an obstacle for development. THIS IS WRONG – parents aren’t an obstacle. When parents are taken out of their picture, their guidance still lives on through their children. Parents play an instrumental role in the development of superheroes. But they remain an often overlooked part of superhero comic analysis.

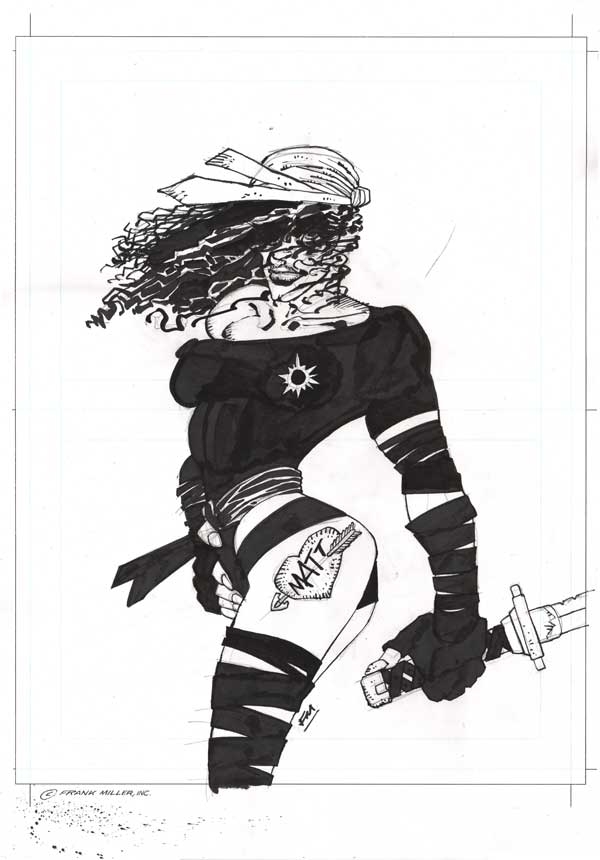

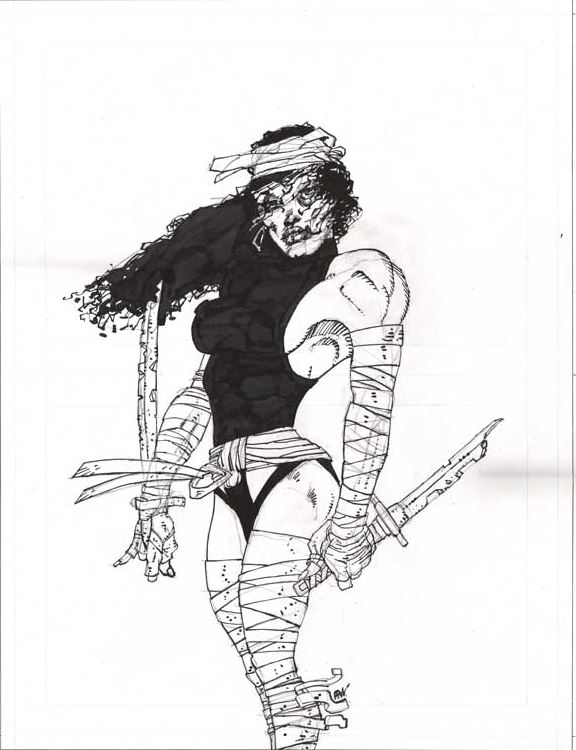

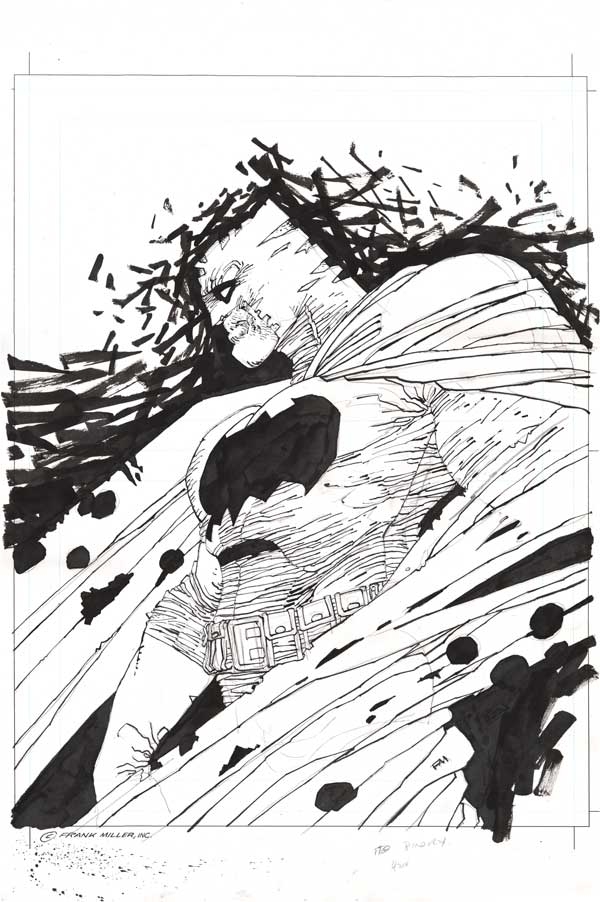

How did Bruce Wayne become a superhero when he has no powers? Bruce and his parents were walking home from a movie when a gunman held them up and shot both Mr. and Mrs. Wayne mercilessly. This moment was incredibly emotionally painful for the young Bruce, but it was also a critical moment in Bruce’s transformation. In a panel in Detective Comics following the blood-soaked concrete of his parents’ death, we see a praying Bruce saying: “And I swear by the spirits of my parents to avenge their deaths by spending the rest of my life warring on all criminals.” With those words, Bruce Wayne begins his physical and mental preparation for his later transformation into Batman. Thus, we can see here that it is explicitly stated that he fights criminals because of his parents’ death and their unforgotten guidance.

Later, the reader is introduced to Batman’s future sidekick, Robin. In the introduction, the young man, named Dick Grayson, witnesses the death of his parents on a trapeze ‘accident’. When the boy plans to call the police, Batman stops him and invites the young Grayson to join his vigilante quest against crime. Of course, Robin accepts the invitation. Batman quickly becomes a fatherly figure for Robin, pointing him in the direction against crime and advising him in the same way Grayson’s father may have. Thus, if it weren’t for Batman essentially adopting Dick Grayson, and for the tragic loss of both of the heroes’ real parents, neither Batman nor Robin would be stopping crime.

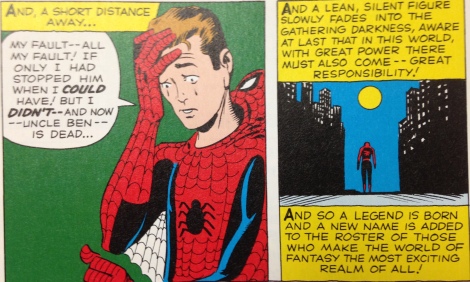

Why did Peter Parker, a nerd mad at the world and given superpowers, decide to use his powers for good? Peter Parker — the “teacher’s pet”, “science nerd”, “mama’s boy” of high school — is given supernatural powers in a classic superhero development story. An irradiated spider falls from the ceiling and bites Parker, shocking him with a jolt of power relative to that of a spider. Needless to say, Peter’s life changes – now the kid who got bullied has an opportunity to be the bully. Prior to the surge of power, Peter had said that he loved his aunt and uncle but that “the rest of the world could go hang, for all [he] cares!” Initially, Peter’s childish attitude and apathy towards helping others with his new powers leads him to miss an opportunity to save his uncle from death. Consequently, Parker proceeds to have a life filled with regret. He feels forever in debt for the guidance that uncle Ben gave him, and he also feels a responsibility to help his aunt May because of her becoming a widow. Uncle Ben left Peter with some extremely valuable words, and Peter never forgot them: “With great power there must also come – great responsibility.” Those words define Peter, and uncle Ben’s death serves as an awakening for Peter to recognize the importance of helping others. Still, it is aunt May that serves as his constant reminder to always act with honor.

Ms. Marvel is not a classic comic. It’s maybe not even a comic you’ve heard of unless you are an avid superhero comics reader. However, Ms. Marvel has gained significant media attention since its publication because of how different its protagonist is from many other superheroes. She is given her powers from a spiritual hallucination of Captain Marvel. Kamala Kahn struggles through her teenage years until this Captain Marvel offers her an opportunity to change and to break away from her overbearing parents. Kamala had been feeling pressure from her parents and was stressed about her identity, so this transformation allowed her to develop into a hero. Initially, Ms. Marvel is uncertain about what to do, but before she can seek action, the excitement finds her. Before entering the scene and helping a drowning girl though, Ms. Marvel recalls a lesson from her father that reminds her that “whoever saves one person, it is as if he has saved all of mankind.” With this lesson in mind, Ms. Marvel acts heroically. She continues to act with this moral compass throughout the story, and several more times she attributes her good deeds to the guidance of her parents. Thus, it is the overbearingness of Kamala’s home that forces her into rebellion and leads her to her powers, and then it is the guidance of her parents that make her a true hero.

Many of us would perhaps call your own parents “superheroes”. In our lives, it is our parents who enable us to face stress and to feel loved. With this idea in mind, it is unimaginable to consider a world without them. Incredibly, both Bruce Wayne and Peter Parker harnessed their emotions and used events relating to family and past guidance to turn themselves from powerful people into superheroes. Meanwhile, Kamala Kahn gained her powers because of a dislike for her parents’ control, but then trusted her parents’ advice most in hard times. Thus, all of these characters gained their powers by different means, but they all are superheroes because of the everlasting guidance of their parents.