This first ran on the Dissolve.

__________

Uwantme2killhim?

Director: Andrew Douglas (NR, 92 min.)

Screenwriter: Mike Walden

Cast: Jamie Blackley, Toby Regbo, Joanne Froggatt,

Distributor: Tribeca Films

Rating: 1.5 stars

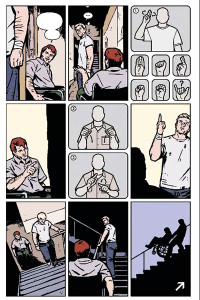

Uwantme2killhim? opens with a police interrogation; Inspector Sarah Clayton (Joanne Froggatt) questions high school-aged boy Mark (Jamie Blackley) about why he stabbed his friend John (Toby Regbo). The scene is functional — it’s a teaser, drawing the audience in with the promise of excitement, blood, scandal, and mystery. But it’s also thematic, framing Mark as a clinical issue to be solved. He is presented, first of all, as deviant, and the rest of the film is devoted to investigating the root of the deviance. Mark isn’t, primarily, a person. He’s a scandal — an occasion for the audience to express both horrified titillation and titillated horror.

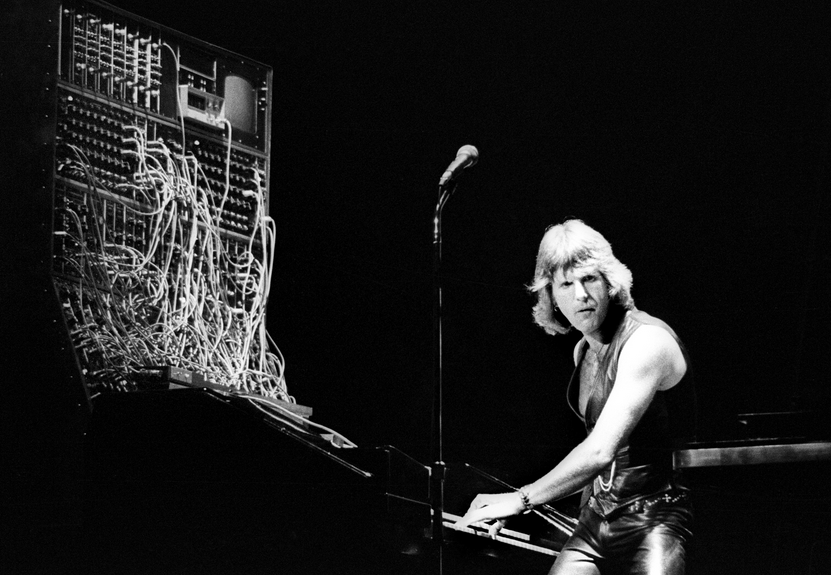

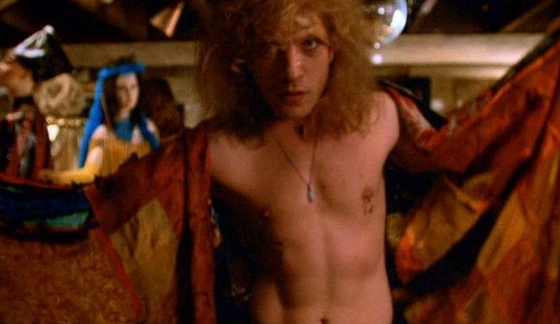

In short, this is an exploitation film. Where Anita, the Swedish Nymphet focused on the problem of “nymphomaia” and Reefer Madness focused on the problem of marijuana, the updated occasion for moral panic is the internet. Mark is a healthy, charismatic young British lad, good at football, popular with the girls (one of whom removes her shirt for him and the camera less than 10 minutes in — just in case there was any doubt about that exploitation film designation.) But he is obsessed with online chat partner Rachel (Jaime Winstone) — an obsession that quickly turns dark and then weird and then weirder. Rachel’s abusive boyfriend threatens Mark online, then murders Rachel…and then MI5 gets involved (online too, of course.)

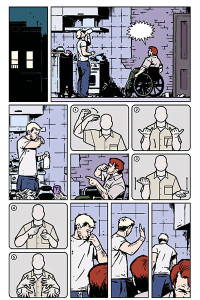

All these internet interactions are presented as oddly hyper-real melodrama. Mark and his interlocutors talk out loud as they type, and the camera switches back and forth between them, so that, instead of one guy staring at the screen, you get a doubled drama. Mingus Johnston as the evil boyfriend, Kevin McNeil, is particularly over the top; mugging and snarling like a parody gangster. But MI5 agent Janet (Liz White) is also coldly ridiculous, somewhere between bland mannequin and buttoned up queen bitch noir temptress.

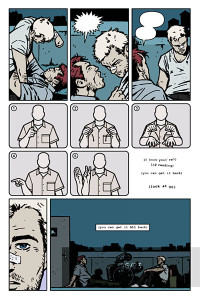

Offline, the main relationship of the film is between Mark and John, Rachel’s bullied brother. In its focus on this close, intimate, confused bond between two young people, not to mention in its based-on-a-true-story pedigree, uwantme2killhim? recalls Heavenly Creatures. But where Peter Jackson was fascinated with his female protagonists’ relationship first and the crime as an outgrowth of that, uwantme2killhim? doesn’t much care about how the boys feel about each other. Indeed, the mechanics of the film are devoted almost entirely to obscuring their interactions. Ostensibly this is because Mark doesn’t himself understand the relationship. But really, it seems like the confusion is meant to create plot surprises for their own sake. As in an Agatha Christie novel, the investigation must end with a twist — and, as with Agatha Christie, information is ruthlessly manipulated, without regard to character or probability in the interest of the final gasp of revelation.

Christie’s books make little pretense of being anything other than puzzles; The Murder of Roger Ackroyd doesn’t have any particular moral lesson besides “murder is wrong,” which presumably most readers knew going in. uwantme2killhim?, though, it trying for more than ingenuity. It’s trying, like an afterschool special, to tell us about the internet, about teen loneliness, about youth today. The pretense of concern combined with the cynical manipulation of the plot for cheap thrills is both transparently hypocritical and broadly repulsive. Too calculated for campy exploitation fun, it settles instead for the dreariness of shocked revelation, a kind of tabloid journalism on screen.