First time I saw a comic book by Bill Sienkiewicz (I’m told it’s pronounced sinKAVitch), my tiny adolescent brain exploded. It must have been one of his early New Mutants, so summer of 1984, just moments before I stumbled off to college. It wasn’t just that the cover was painted (I’d seen New Defenders do that the year before) but how dizzyingly un-comic-book-like his art looked to me. It took thirty years, but I finally have the words to describe it.

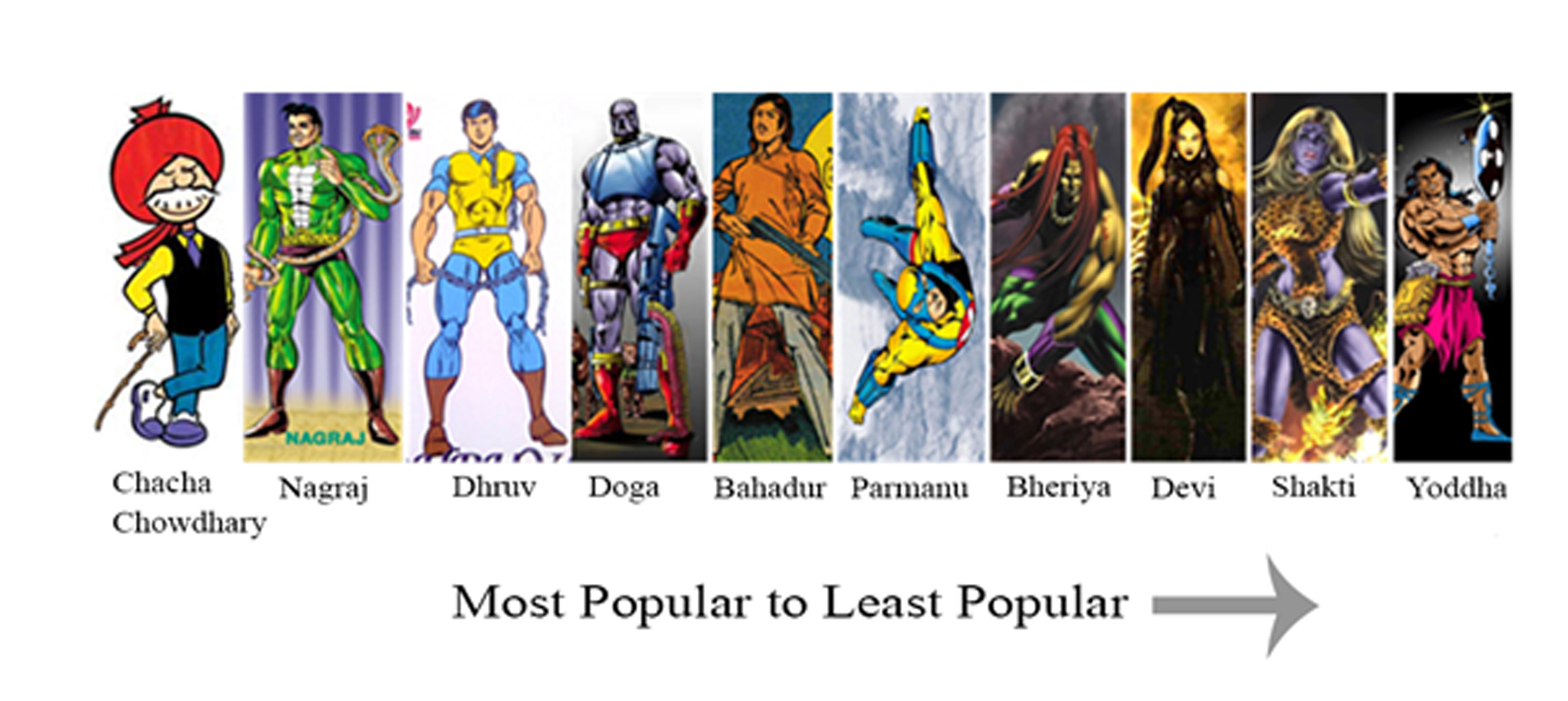

Last week I offered an Abstraction Grid, a 5×5 breakdown of comic art according to amounts of detail and exaggerated contours. It looks a lot like a bingo board, and since I know of no comic artist with a wider range of styles than Sienkiewicz, he’s my first player.

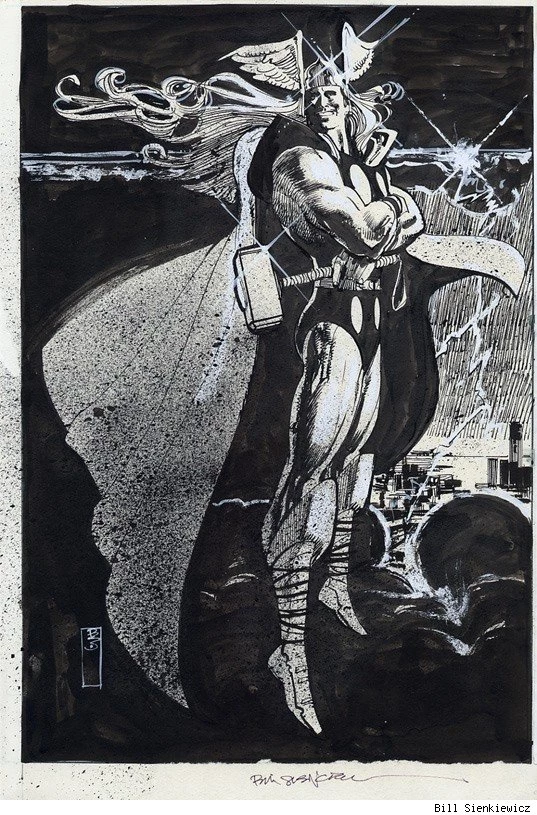

Bingo starts with a free space, that one right there in the middle, and comics do too. The middle square is 3-3 on the grid, the style of most superhero comics. It combines a medium amount of detail (I call it “translucent” to differentiate from the two ends of the scale, “opaque” and “transparent”) and a medium level of exaggeration (I call it “idealization,” that sweet spot nestled between line-softening “generalization” and shape-warping “intensification”). Sienkiewicz, like most comics artists, started his career in the middle square:

3-3

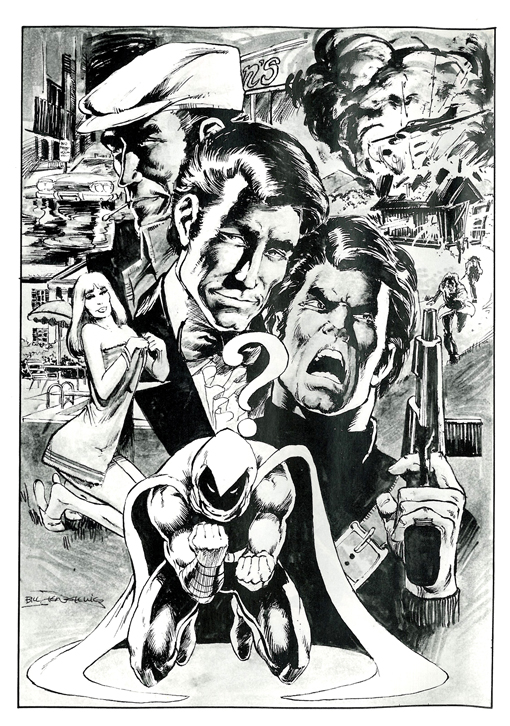

I vaguely remembering seeing some issues of Moon Knight as a kid, but the art didn’t register as anything special, because that was Marvel’s Bronze Age Prime Directive: draw like Neal Adams.

Perfectly good style, but if you slide over a square to the left, more detail is more interesting:

2-3

Sliding to the less detailed right is fun too, stripping those idealized forms down to something a little more basic:

4-3

Sienkiewicz can go even further, reducing subjects to minimal details, sometimes just undifferentiated outline shapes.

5-3:

1-3 is rare in comics, but disturbingly common in advertising. Photography provides the maximum amount of details, and Photoshop lets you idealize them:

The fourth row of the grid is intensification. Where idealization magnifies and compresses shapes but stays mostly within the bounds naturalism, intensification steps out of bounds, usually by throwing proportions out of whack.

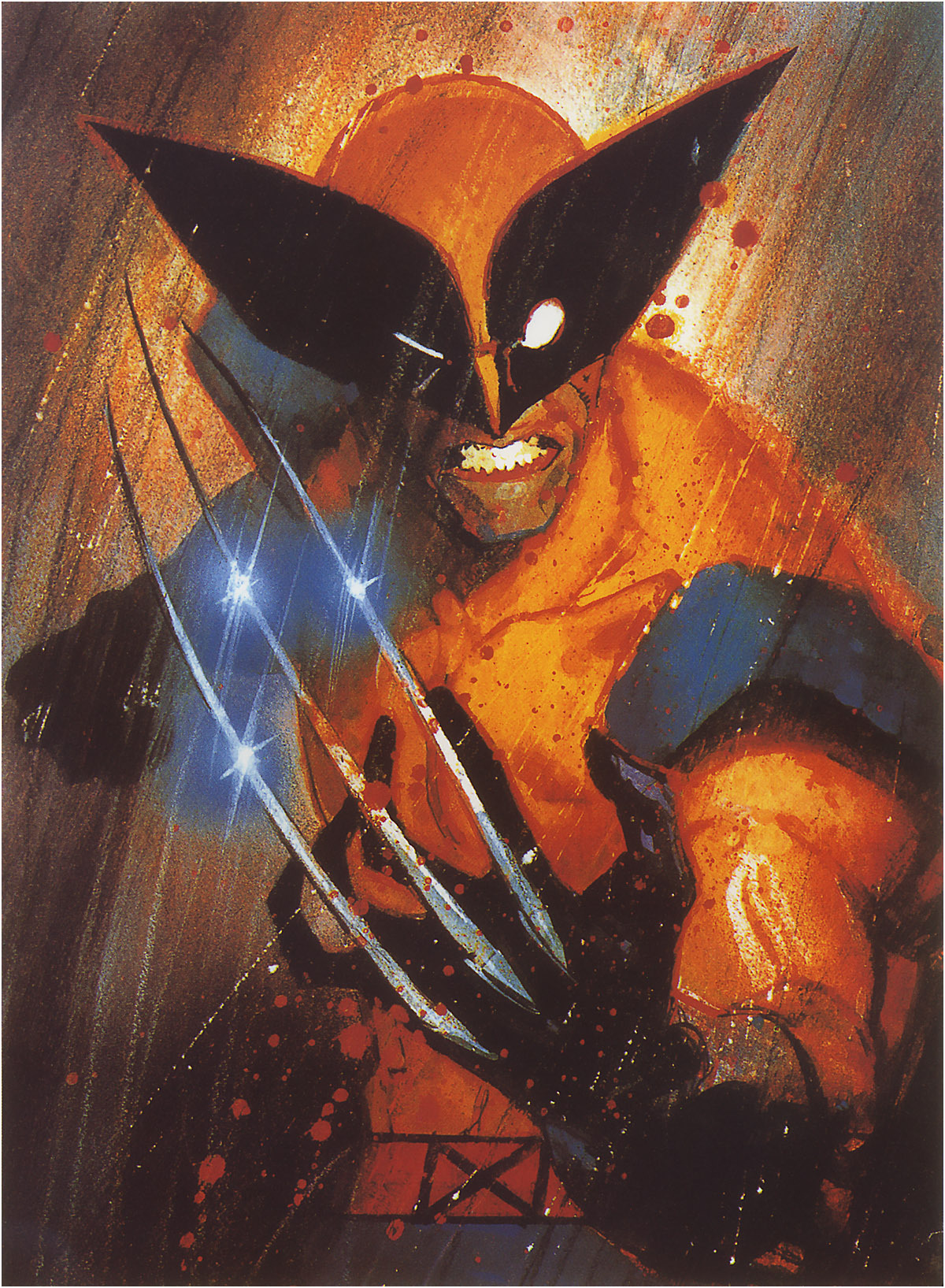

Seinkeiwicz is a pro:

3-4

The exaggeration is more pronounced with more detail:

2-4

Less detail creates a more of a classic “cartoon” effect:

4-4

Meanwhile, the left half of this Stray Toasters face strips away eve more detail, so only the minimal number of lines remains:

5-4

And the sparse lines of this torso are impossibly regular too:

1-4 is rare, but sometimes a fashion ad blows it by Photoshopping beyond idealization and into inhuman intensification.

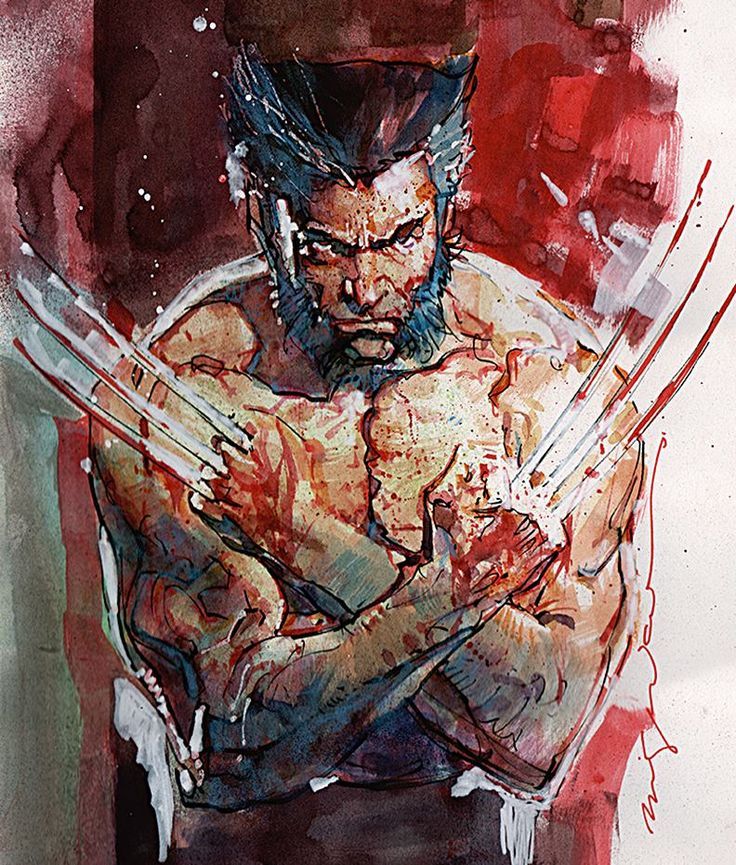

I call the top range of exaggeration hyperbole because it breaks reality completely. Sienkiewicz is one of the few comics artists who spends any time this high on the abstraction grid. His minutely detailed yet absurdly proportioned Kingpin from Daredevil: Love and War is one of my all-time favorites:

2-5

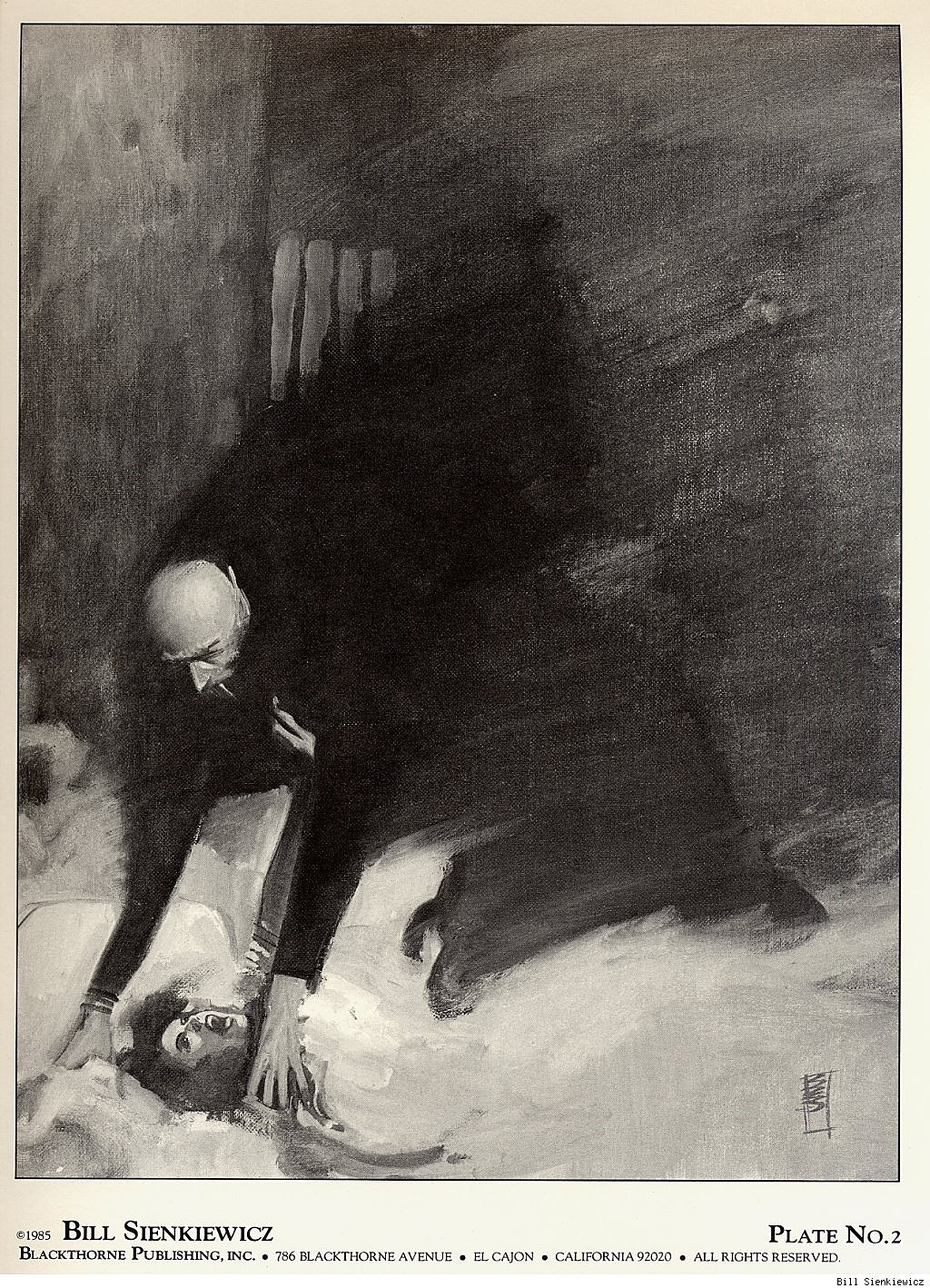

The Demon Bear by itself is 3-4 intensification, and the figure of the New Mutant facing it is your standard 3-3, but the combination steps into hyperbole:

3-5

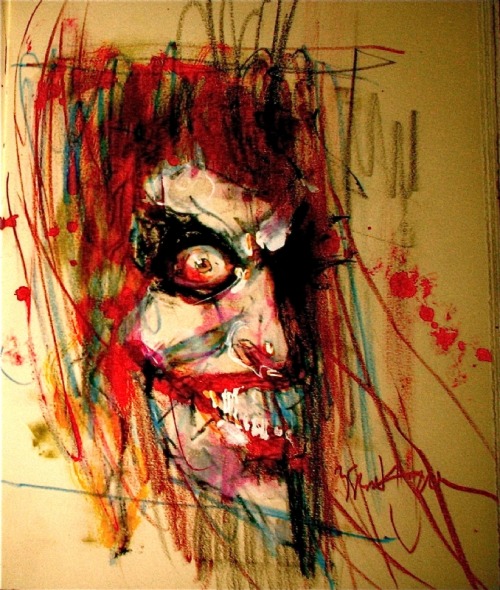

These scribbles of Joker’s face and body are simpler but exaggerated to a similar level of unreal.

4-5

And then there’s cartoonish chaos of Warlock’s Bill the Cat face:

But, like most superhero artists, Sienkiewicz spends almost no time up in 5-5. That’s South Park terrain:

For 1-5 photography, stop by Celebrity Photoshop Bobbleheads:

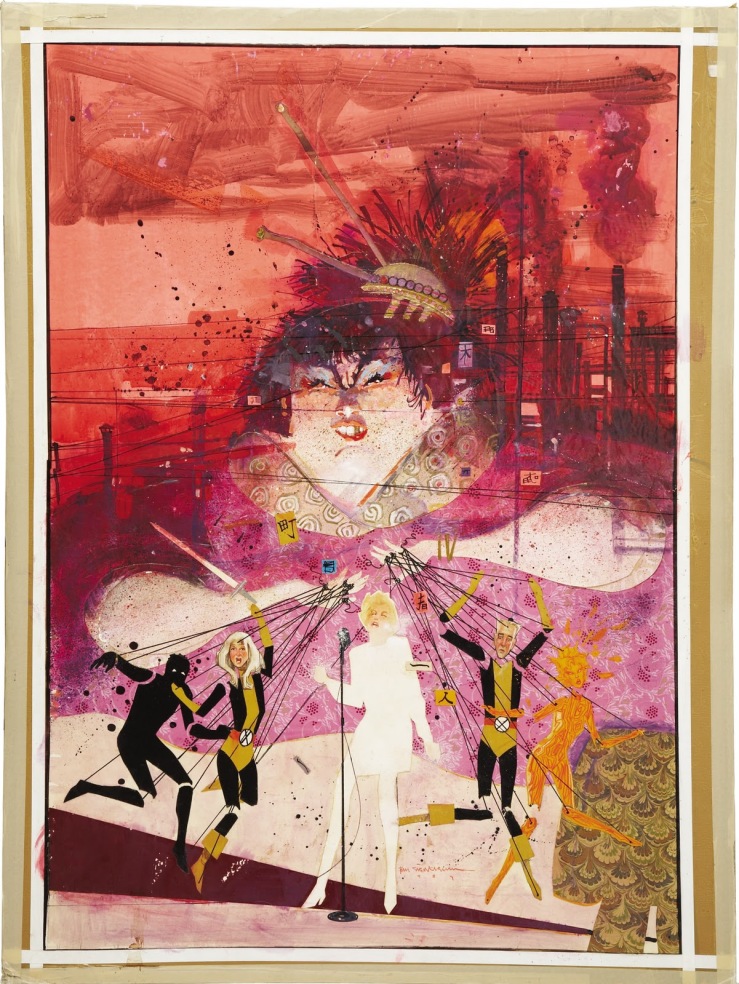

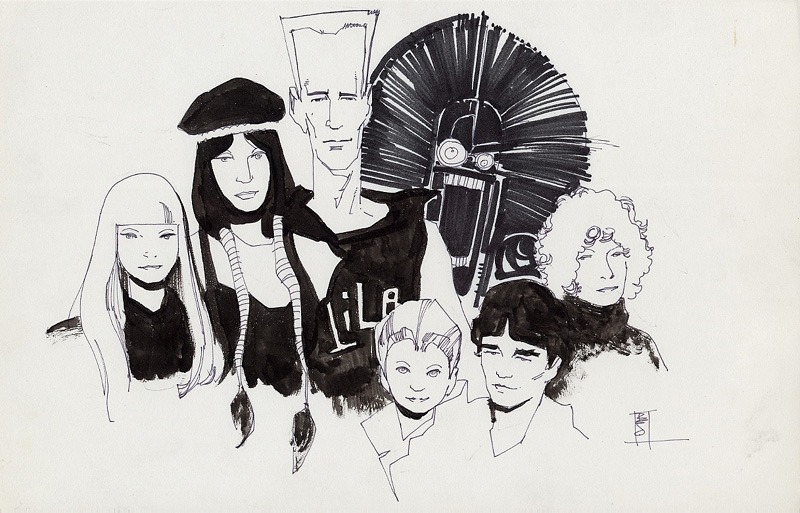

Moving back down the grid now, the second row of shape abstraction is generalization, just a slight tweaking of line quality. The New Mutants here have a typical level of detail for a comic book, but the those lines evoke real-world subjects.

3-2

Some of these New Mutants (not Fireball and Warlock though) look distantly photographic, though with even less detail:

4-2

While this portrait of Lance Henriksen is dense with detail:

2-2

5-2 is rare, a fully realistic human figure in outline only. And most 1-2 photography hides its Photoshopping so well it registers as undoctored photography.

Seinkeiwicz spends time in that photorealistic corner too though.

1-1

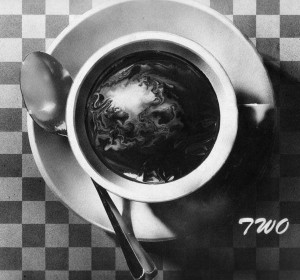

This next image from Big Numbers may be an altered photograph, with just a little detailed flattened.

1-2

1-3, 1-4, and 1-5 are rare since it defeats the point of photorealism to strip too many details away.

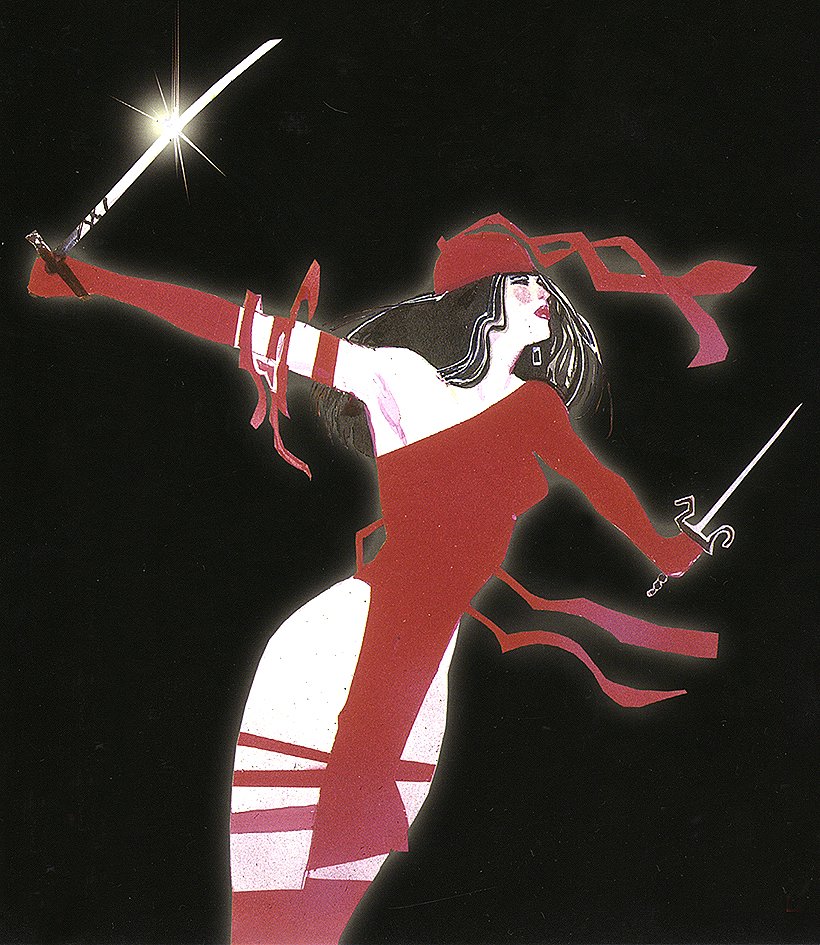

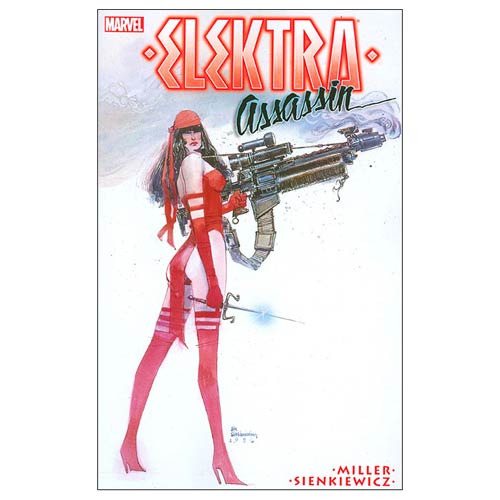

Finally, notice that many of Seinkeiwicz’s best effects are a result of using more than one kind of abstraction in a single image:

The overall figure is 3-4 intensification (humans are not roughly 2/3rds legs). But while the top half of the figure has a medium level of detail, the legs are flat with not a single line of shadings, so 4-4. And though the gun is intensified too, it is impossibly large in relation to the figure, and so 3-4.

Skim back up the other images for more of these combo effects.

Meanwhile, how well did Bill do on the Abstraction Board? I count 16 out of 25 squares filled. Let me know if you find an artist with a higher score.