This first ran on Splice Today.

___________

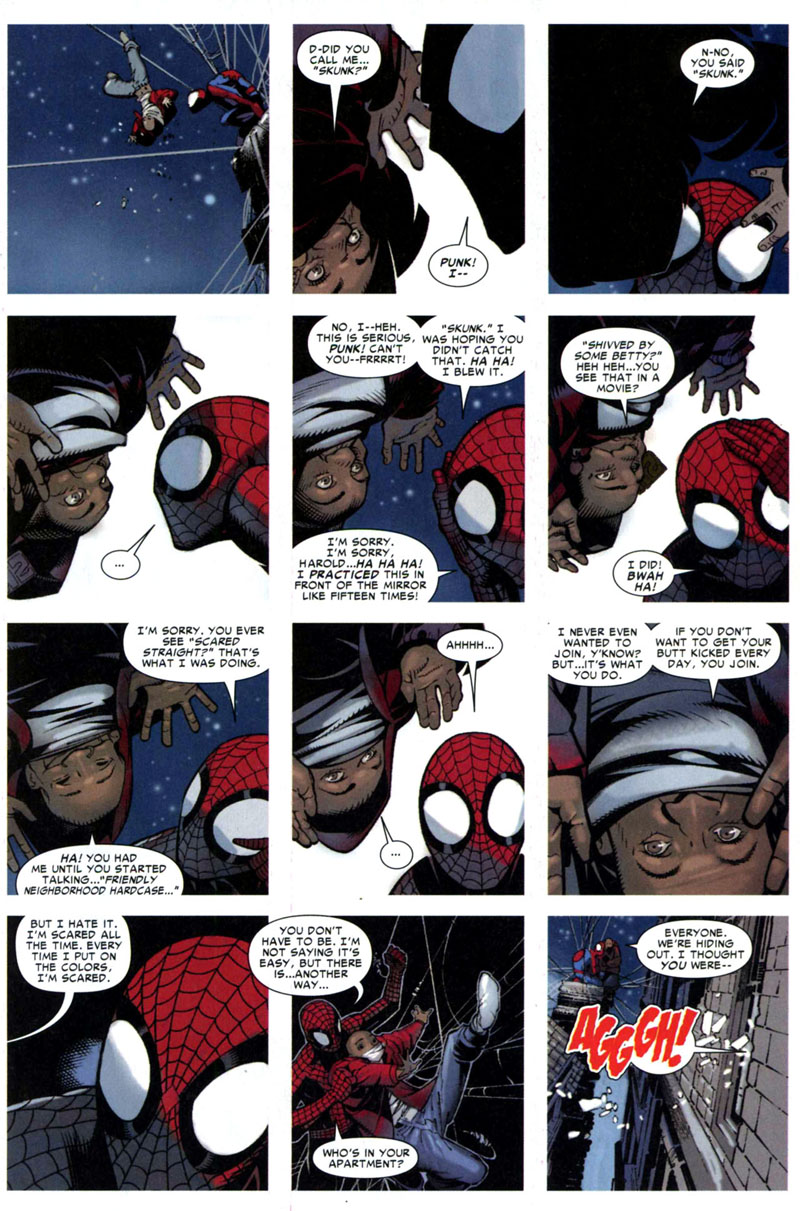

Writing gets demystified pretty quickly when you do it for a living. All the stuff you hear in creative writing programs about cultivating your own voice or writing what you know or making the familiar strange — pretty much nobody who will pay you actually gives a shit. Instead, the kind of things your clients are likely to focus on are, can you meet a deadline? Can you be just as entertaining and accessible as we’ve decided the audience would like you to be, without being so entertaining and accessible that someone gets offended? Can you figure out something to say about dietary supplements without instantly revealing that neither you, nor we, nor really anybody cares about dietary supplements? In short, can you competently jump through the hoops at your boring day job the way that everybody else has to jump through the boring hoops at their boring day jobs? And can you do it without too many glaring grammatical errors?

Like I said, you figure all this out fairly quick. Or, at least, it seems like you would. Not Anna Davies, though. Davies is, she tells us right at the beginning of her essay a “real writer” — and as proof, she says she’s ghost-written a massively popular YA series. She clearly intends for us to be impressed — and, hey, I can oblige happily enough. I was impressed. Ghost-writing a massively popular YA series— that sounds like a great, relatively enjoyable source of steady income. I’d do it if I had the chance.

Anna, though, doesn’ t present it as an enjoyable source of steady income. Instead, she makes it sound like some sort of Faustian bargain, in which she sold her inner glittery snowflake for ugly, mundane cash. She’d wanted to be a famous YA writer herself, but all she did was write other people’s series. She buried her muse so thoroughly that even her editor tells her, “You write well, but nothing has heart.” To which she replies, in a transcendent psalm of self-pity:

“Of course nothing did. I’d given it to them. I’d given them my time, my talent, my 20s. And that was the lesson that had somehow gotten buried as I learned to create characters, set scenes and turn around a revise in three days: Never give more than you’re prepared to lose. In the course of five years and approximately 600,000 words, I’d become so good at mimicking the voice of another author that I’d lost my own, and I’d failed to nurture my own career, not to mention well-being, as carefully as I had the lives of the characters that had never belonged to me.”

Davies has written for the New York Times and Marie Claire, and is making her declaration of failure from Salon. Clearly, she spent some time in there nurturing her career. But putting that aside, what exactly is she complaining about here? That all her dreams didn’t come true? That she had to work at a job that was occasionally unpleasant and felt like work? That after five years she’s only a quite remarkably successful writer rather than being J.K. Rowling? I don’t mean to be cruel, but, jeez, buck the fuck up.

To be fair, when you read the whole essay, you get the impression that there is more going on with Davies than she is quite willing or able to explain. She talks about her mother’s death; she talks about drinking too much; she talks about relationship failures. It doesn’t exactly add up, but for whatever reason, she’s obviously quite unhappy. I don’t think she’s lying about that, and I certainly don’t blame her for it.

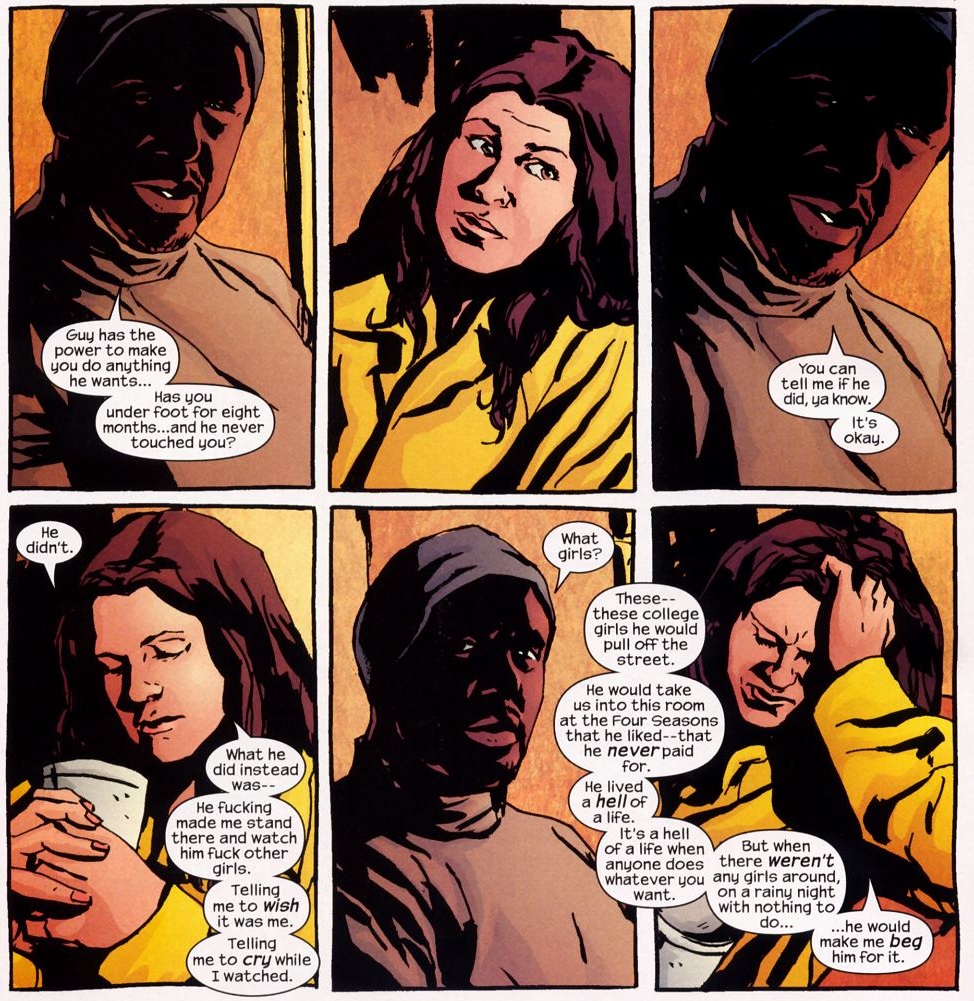

Still, for a working writer, it is kind of irritating to see my profession presented as some sort of catastrophic self-betrayal, and/or as leading inevitably to a dark night of the soul. Reading it, I felt (presumptuously, but still) like I’d gotten a little glimpse of how sex workers feel when they have to sit through yet another documentary about how debased and miserable they are. Work for hire can be exploitive and depressing just like any other job, of course, and sometimes folks will treat you badly (or in the worst case not pay you.) But there’s nothing about it that’s inherently demeaning, or no more so than any other kind of employment.

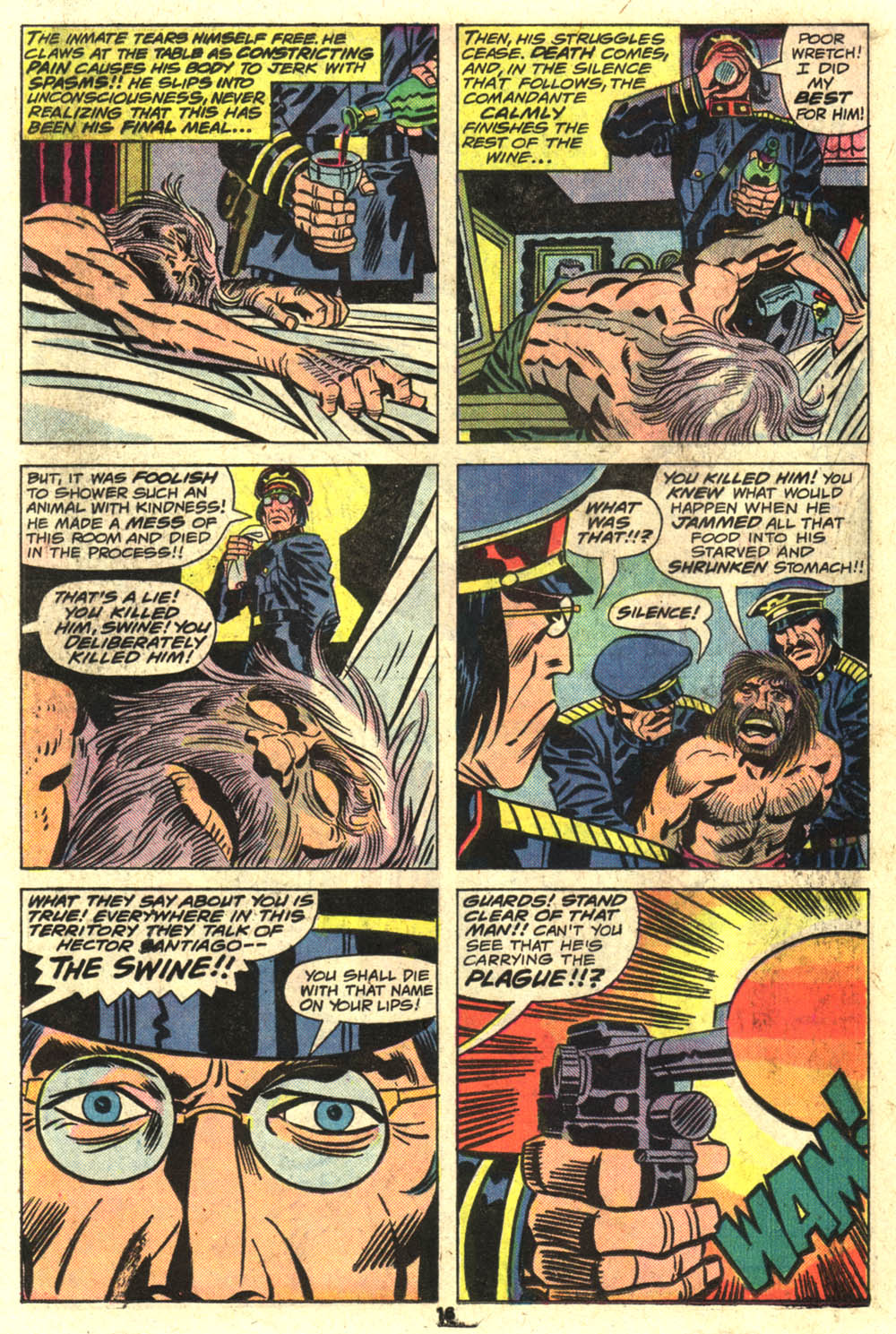

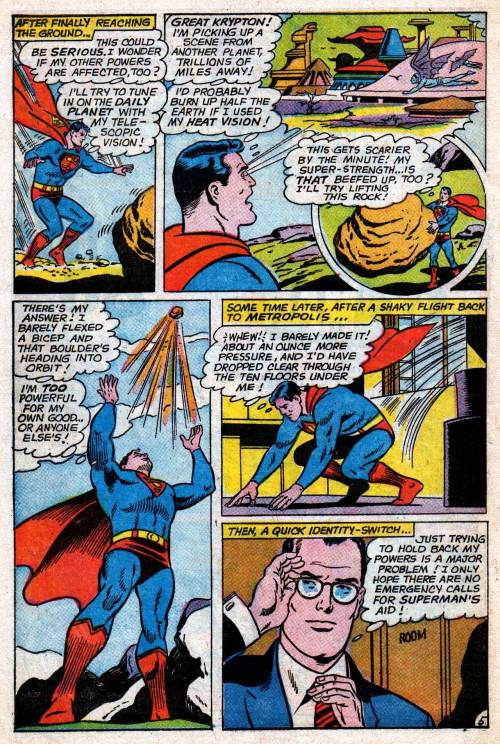

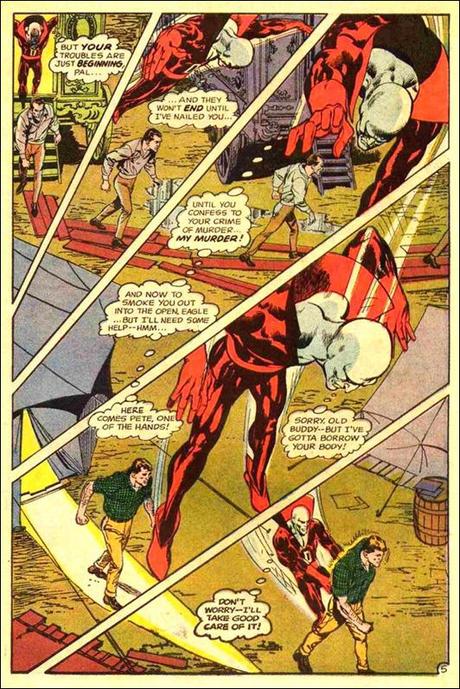

Davies though, thinks there is. Work for hire function in her essay as a weight and a corruption, the thing that has prevented her from becoming a real writer, or even a real person. It’s like being a ghost writer has made her a real ghost; as if writing for someone else has turned her into no one. She seems, in other words, to have confused her job with her soul, and to have lost perspective in a catastrophic manner on the fact that being a ghost is just a gig. It’s not a sign that you are dying.

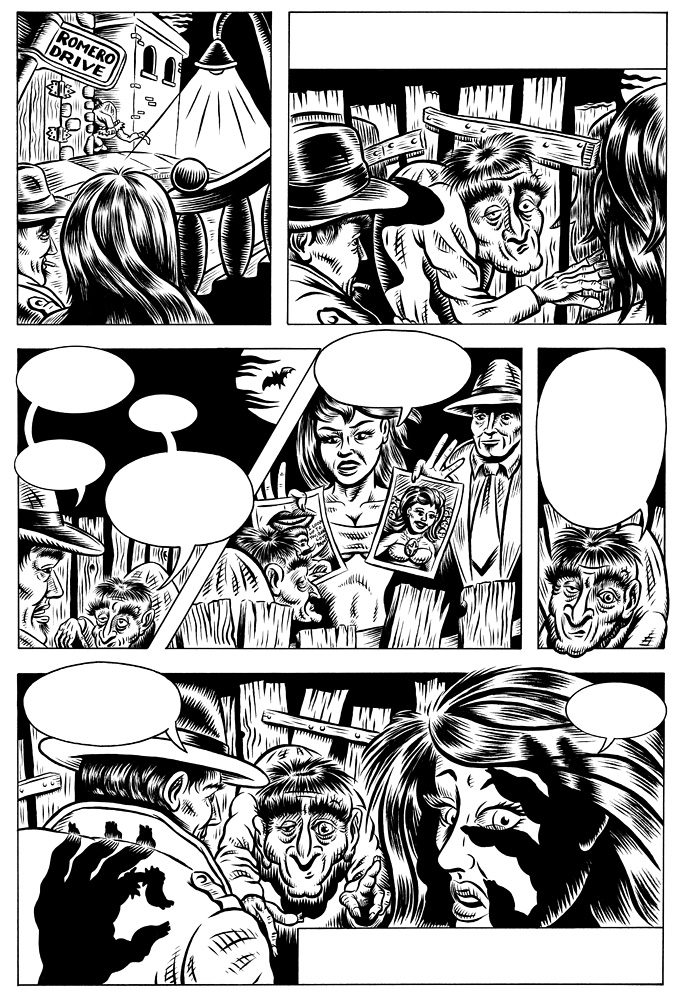

.jpg)

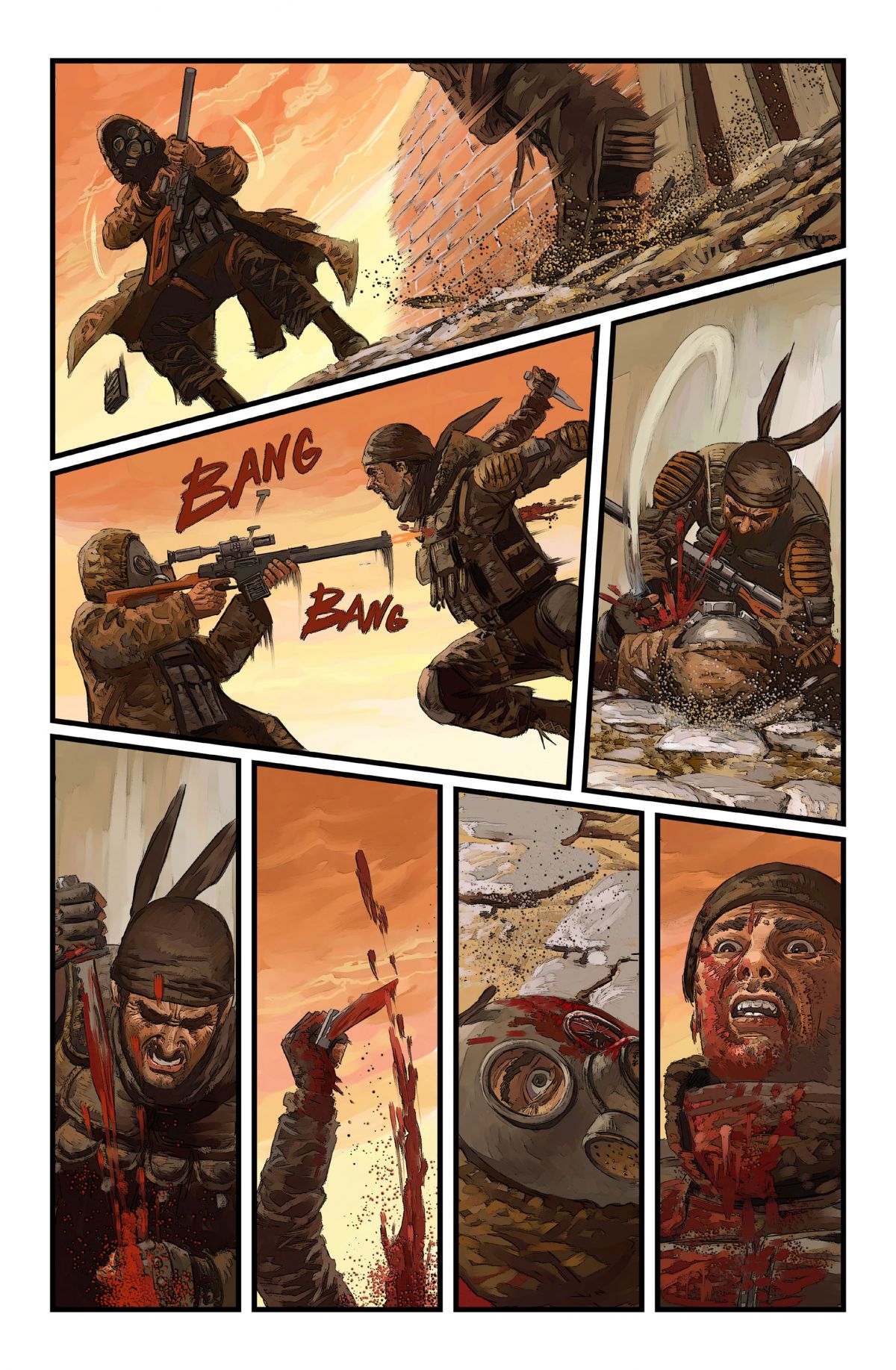

.

.

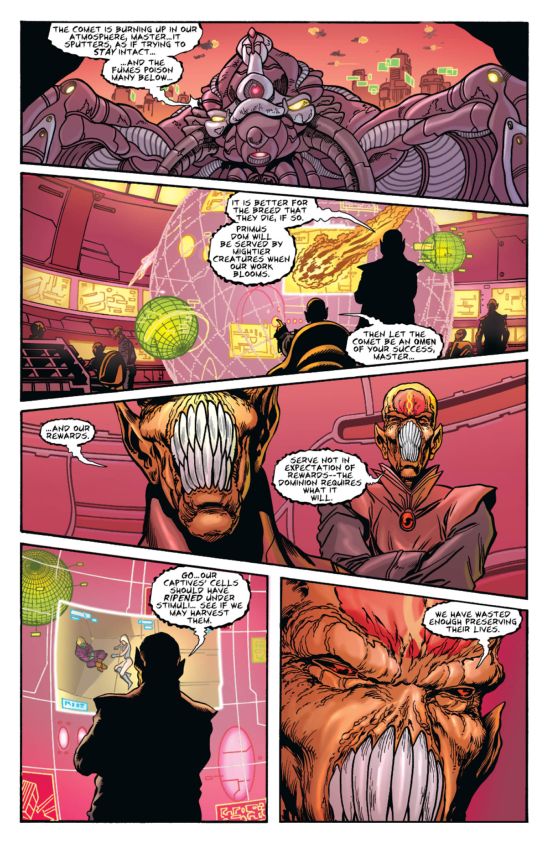

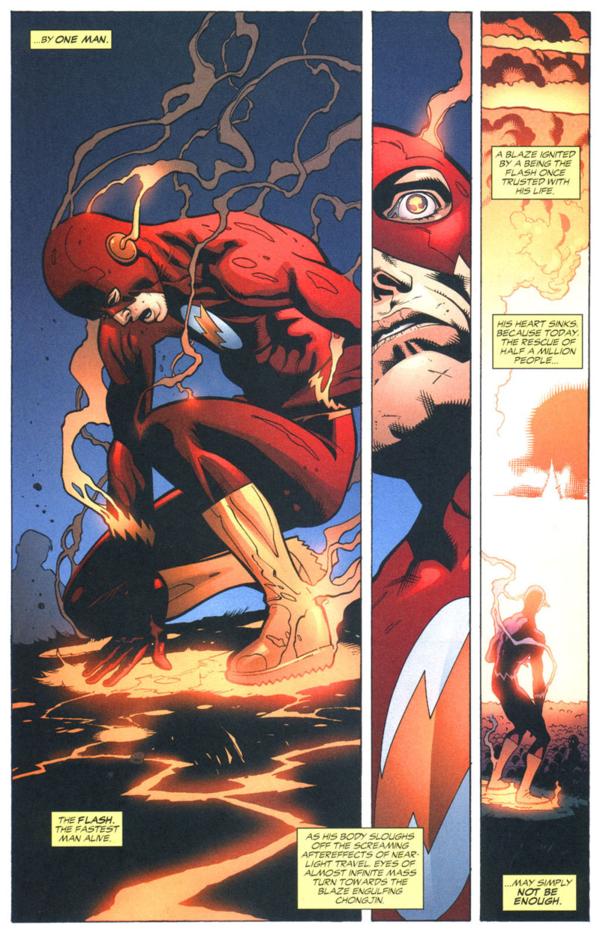

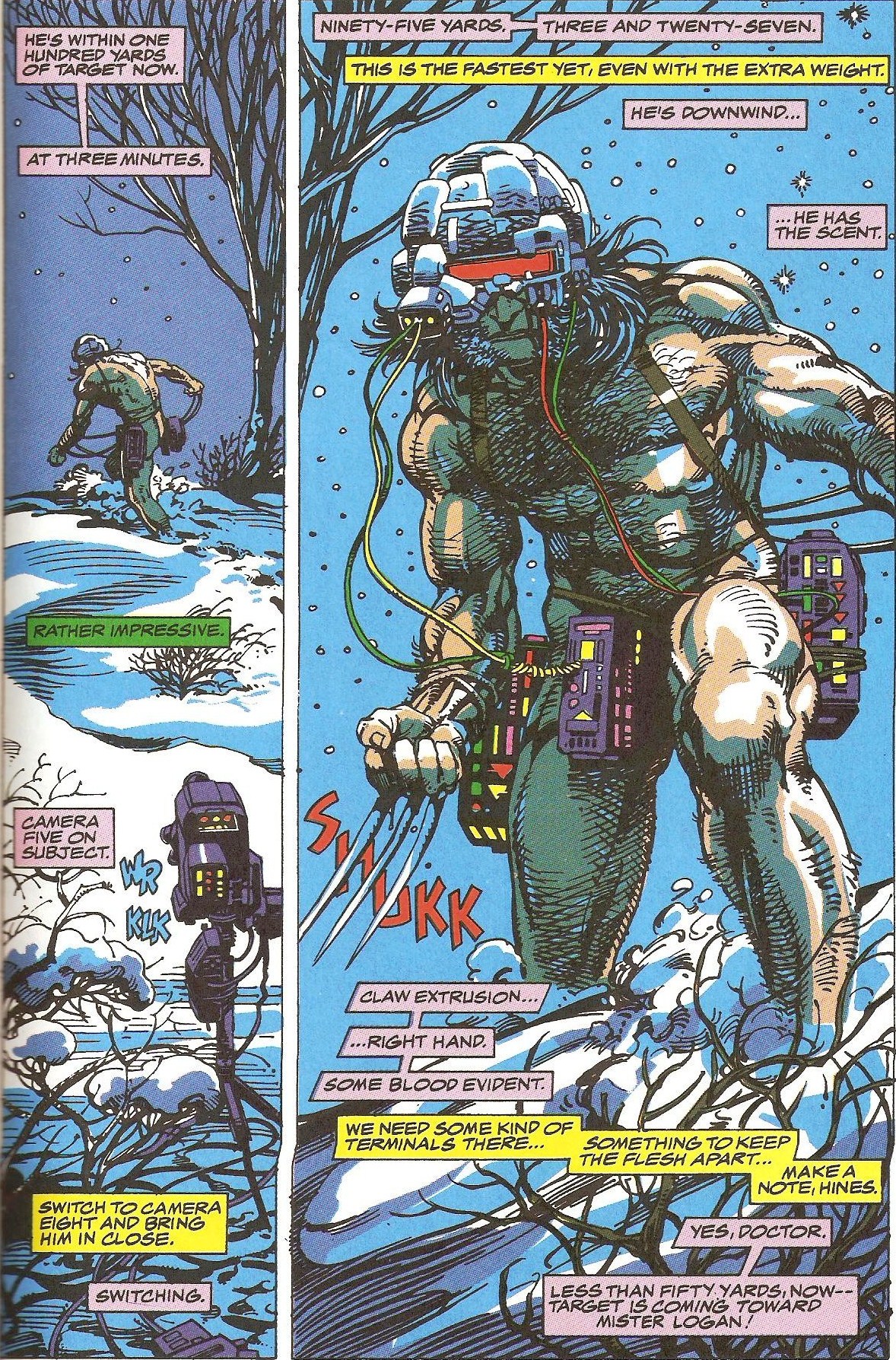

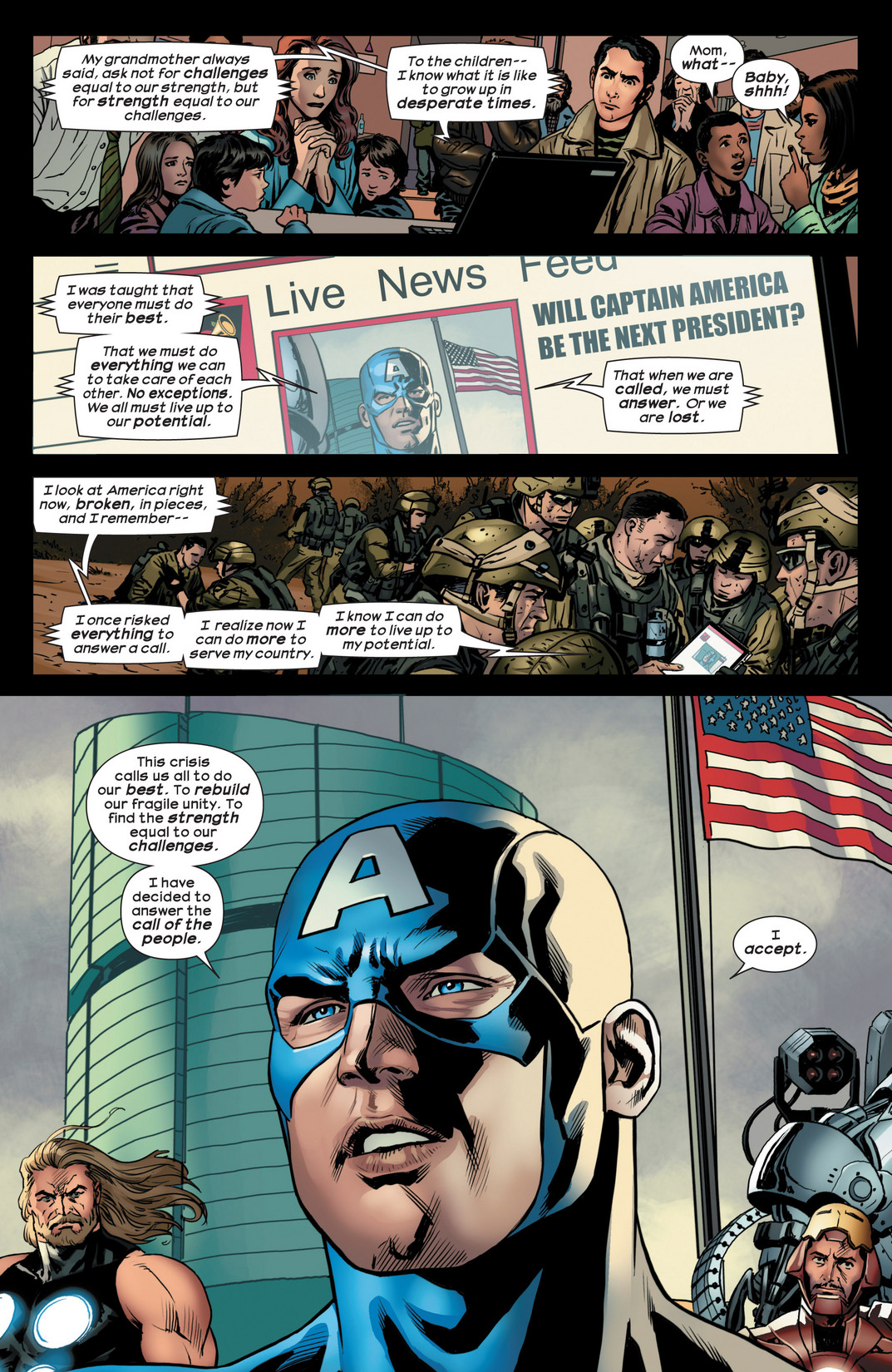

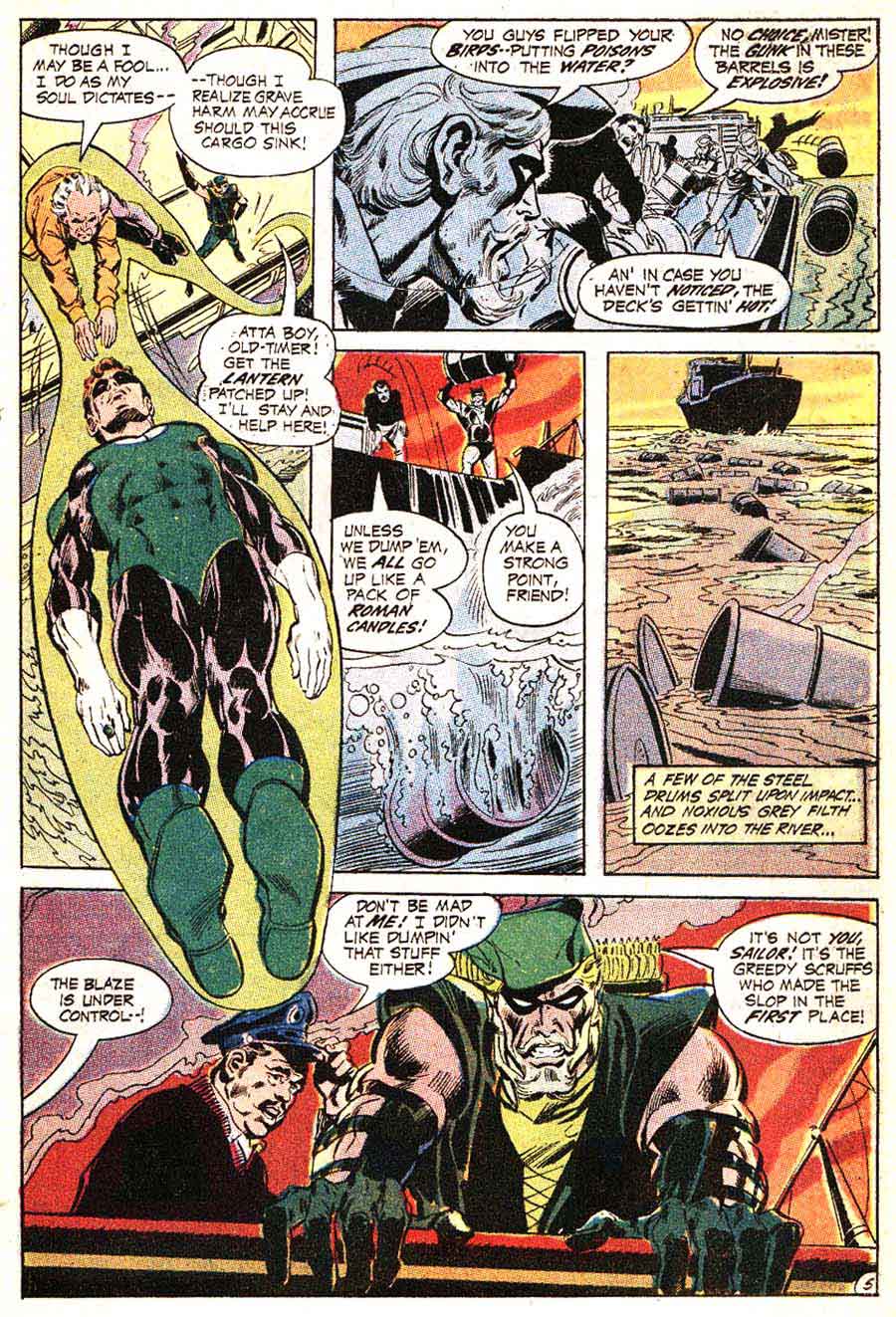

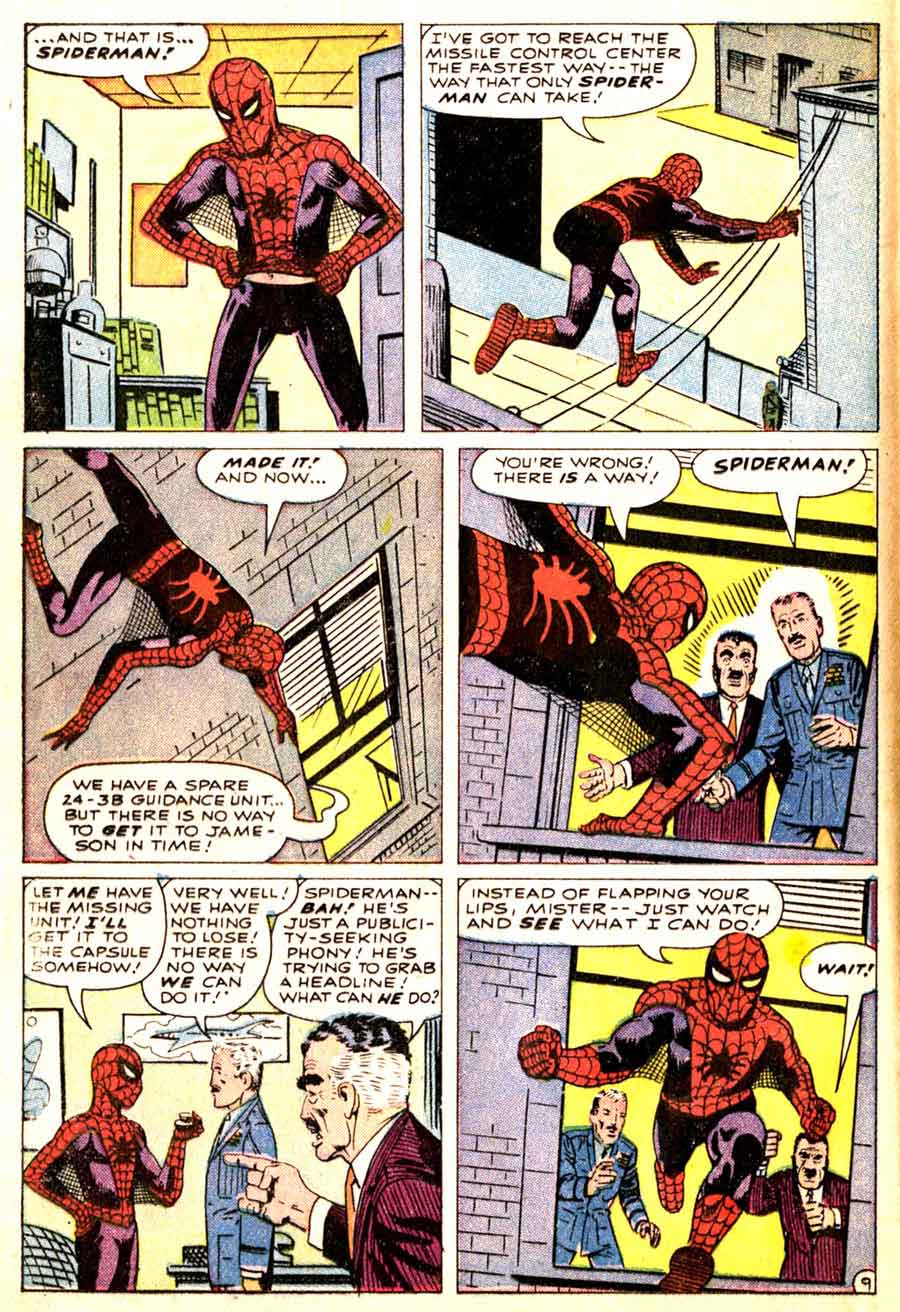

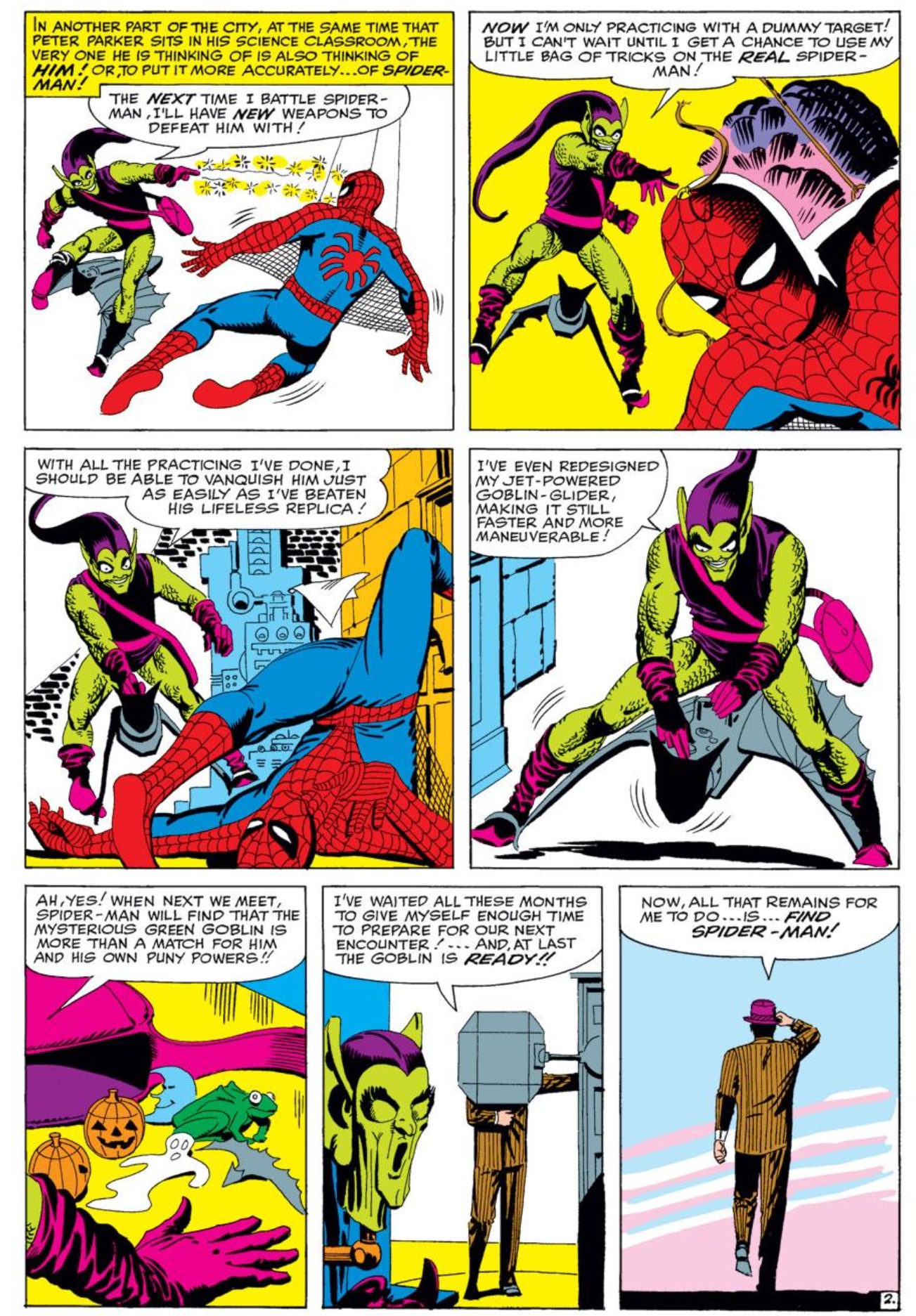

S(5dhqryzjtk4qcdgjv1lbpdjy))/superhero-library/Img/Pages/A1/A1-174-page-004-l.jpg)

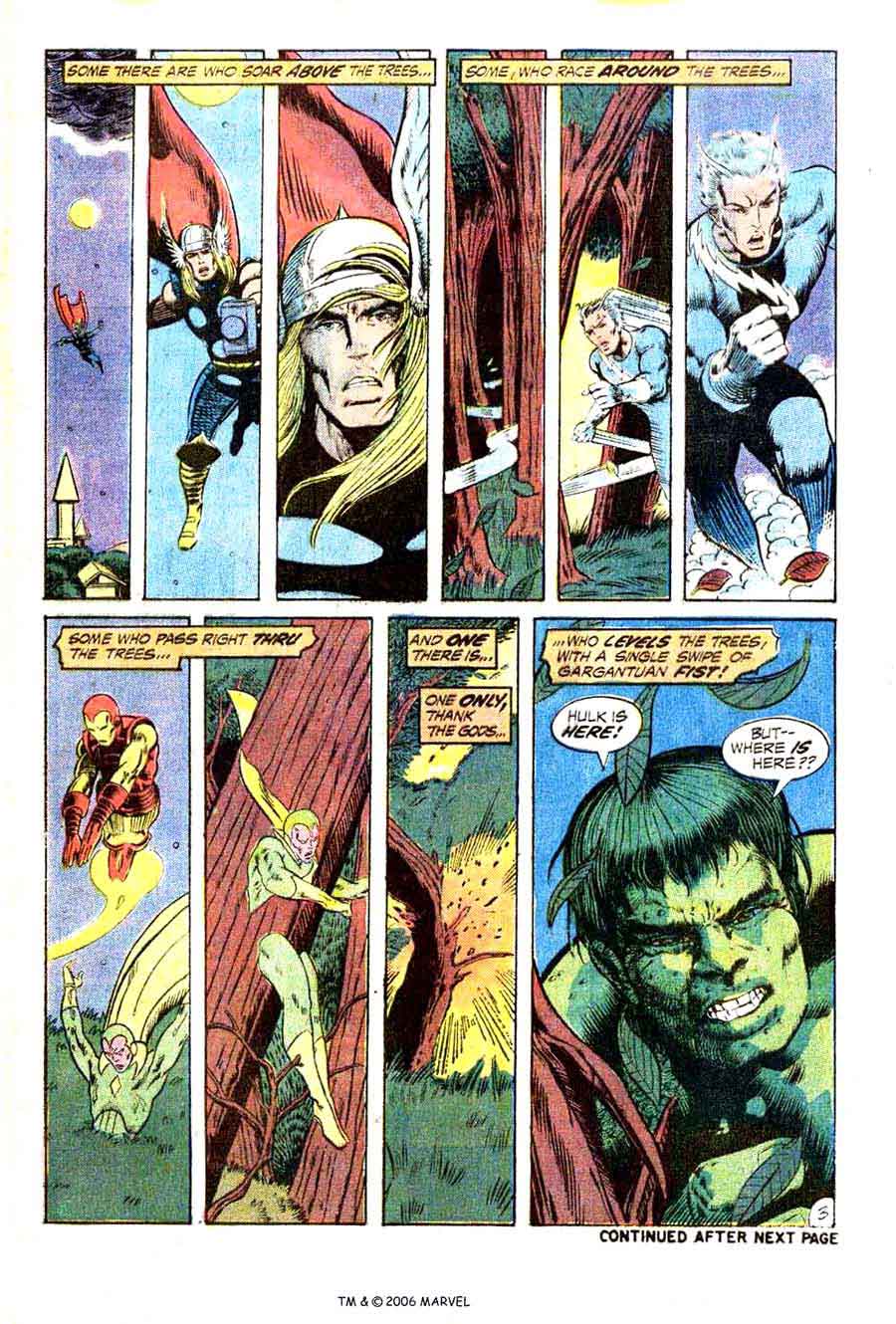

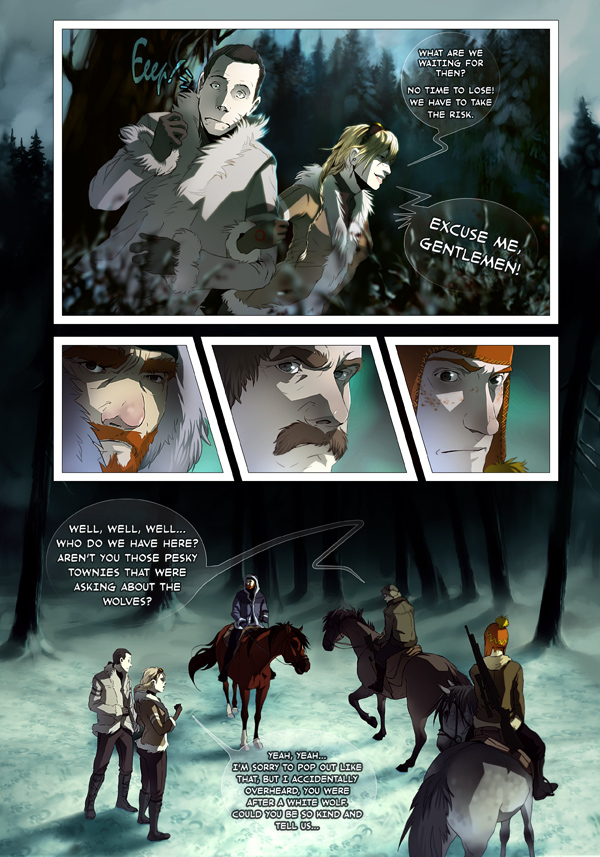

S(5dhqryzjtk4qcdgjv1lbpdjy))/superhero-library/Img/Pages/A1/A1-174-page-003-l.jpg)