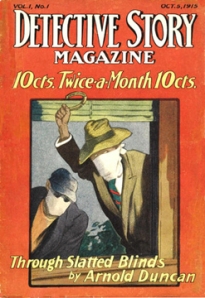

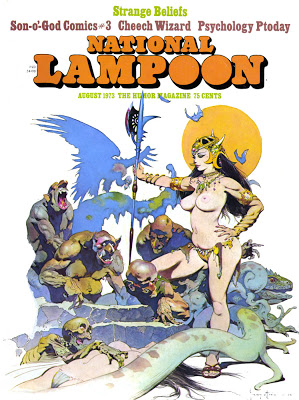

I was seven the first time I saw this illustration. I’d never heard of Frank Frazetta, but forty years later I still recognize the style. I assumed it was an Eerie or Creepy cover, but flipping through online databases and comic-con long boxes unearthed nothing. My memory had added a throne, so my description to vendors didn’t help either.

I knew it was early 70s because I’d seen it during a family vacation in Cape May, NJ. We went multiple years, but stayed only once in the Sea Mist Hotel–on the second or third floor, the right side, in what seemed like an improbably large open space.

An adult cousin–I don’t know which of my father’s nephews–was suddenly staying with us too. He’d arrived on a motorcycle and slept in a sleeping bag in his underwear on the floor. I slept in my briefs, but with pajamas over top, so his relative nakedness confused me, a change in the rules.

The magazine was his. It confused me too. It was sitting on a large table, more or less chin height, as I studied the cover at what must have been a distance of inches. It didn’t occur to me to open it or to pick it up. Though there was nothing taboo in its placement, no sudden parental shuffling of papers, I felt something transgressive. The breasts presumably. I’d seen my mother naked, but this was different, another shifting of known rules.

This was 1973, only months before my parents’ separation. I turned seven in June. Frazetta penned “72” next to his signature, but the magazine logo hides it. I had no idea he’d illustrated a National Lampoon until the cover popped up on my laptop during a recent Google search. No. 41, August, so on stands in July when my cousin grabbed his copy on the way to a beach getaway.

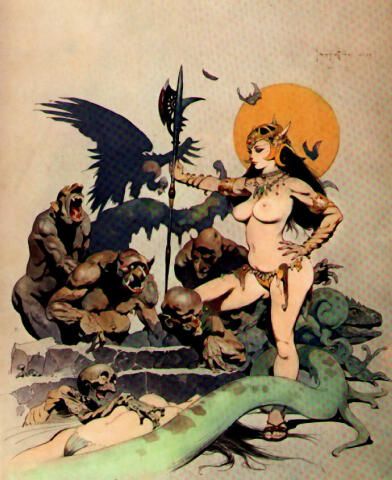

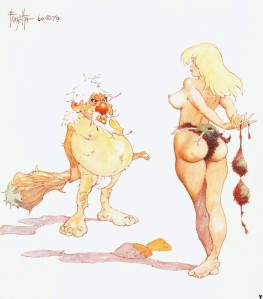

I’m still not sure what it’s doing on the front of “The Humor Magazine.” Frazetta drew the occasional Playboy-esque cartoon,

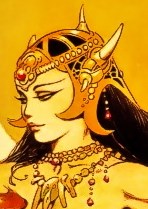

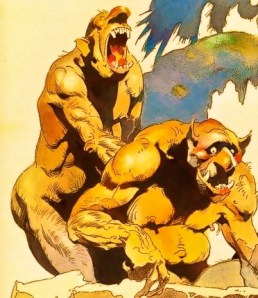

but “Ghoul Queen” is closer to the distortions of his fantasy style. Still, the ghouls are more comic than menacing,

and their queen’s hip-to-waist ratio exceeds even Frazetta’s usual idealized proportions.

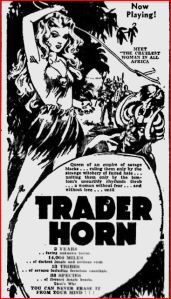

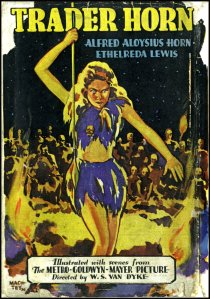

An editor’s note claims he drew it for a previous “Tits ‘n’ Lizards” issue, but that’s just an example of the magazine’s “Humor.” Looking at the cover now, I’m still confused. Female nudity aside, the image seems to be about race. A white woman reigns over her dark-skinned minions. This could be the White Goddess and her African worshipers in 1931’s Trader Horn.

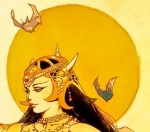

Instead of Aryan curls, Frazetta endows his goddess Asian overtones–or is that just make-up? This bejeweled yet rag-wearing Queen must spend a lot of time plucking her eyebrows.

Despite all the abundant white flesh glowing in front of them, the ghouls’ eyes are averted. The Queen is displayed for the viewer only. The image dramatizes the Mississippi racial rules that Emmett Till violated in 1955. A white woman’s body is always taboo to dark-skinned males, no matter how outlandishly posed.

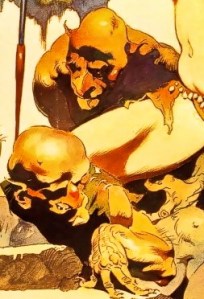

Sculptor Tim Bruckner also suggests a homoerotic dimension to Frazetta’s sex fantasy: “having to decide what some of the ghoul pairs were doing behind her was something best left to the imagination.”

Are those expressions of monstrous pleasure? Are the obscured arms of the rear figures directed toward their crotches? Do the splayed fingers and curved wrists of the foregrounded hands denote submission? Does the apparent orgy explain their disinterest in the Queen’s body, or is this how dark males control their desire for white female flesh? And why the hell did Frazetta draw an extra left hand groping around her hip?

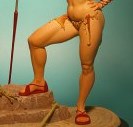

I see other anatomical issues (her face is too small, her breasts too round), but I’m more concerned with the ones I can’t see. Like her right leg. The pose suggests that the knee is bent so that the right calf is vertical, like so:

Except that space is occupied by a ghoul. The Queen’s leg isn’t hidden by his back–their bodies overlap as if collaged from separate planes. The two images don’t belong together. Maybe that’s why the ghouls aren’t ogling their queen, and why her gaze skirts past them too. It would also explain the floating hand. Frazetta was revising. The 3-D impossibility is further augmented by the two-dimensions of the image. It’s a painting, so obviously two-dimensional, but Frazetta emphasizes that fact by not filling the entire canvas. The sky behind the figures and the ground in front of them are the same continuous, unpainted space. He even flattens the vulture so its outlined body is almost as undifferentiated as the moon.

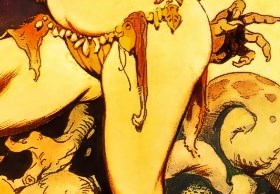

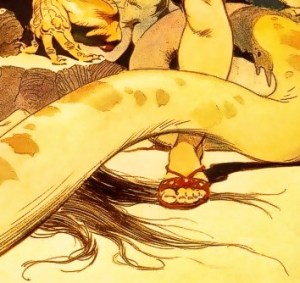

None of this struck my seven-year-old imagination. After an anxious glance at the Queen’s towering authority, my eyes dropped to the discordant subplot at the bottom of the page. The snake offers a range of mysteries (is it attached to the lizard’s head? what are those snail-like appendages?), but I was busy contemplating the two other figures.

I’m tempted to say this is the moment I first realized I was straight. But I didn’t realize anything. I just sensed something inexplicable. When I rediscovered the image online, I wasn’t sure it was the same–where was the throne?–until my eyes dropped to the skeleton’s hand again. I could feel it as if looking at a photograph of my younger self and remembering the sensations of the frozen moment. The dark-skinned ghouls and their domineering queen had nothing to do with me, but that skinless skeleton hungrily pawing an unconscious woman’s body, that’s who I identified with. That was me.

It’s not the cover image to my sexuality I would choose. It merges incompatible desires–is the skeleton’s mouth wide with arousal, or is he (“he”) anticipating a juicy meal? Either way, he’s a predator. Though not, apparently, a hunter. The woman is a discarded scrap, literally below the interest of the queen and her ghouls. Even the snake-lizard stares off indifferently as the woman’s face is obscured by its Freudian body. I understood her then and now to be unconscious, though she might as easily be dead. Perhaps her erect nipples signify living prey.

So my first inkling of sexuality was triggered by a fantastical representation of date rape. The girl’s been roofied. It’s a dire contrast to the Ghoul Queen–a woman commanding a gang of four grotesque but muscular males who have the physical ability to overpower her but instead bend and crawl at her feet (while possibly having anal intercourse). She is the painting’s largest figure, the tallest, spanning nearly the height of the frame, her figure embodying unchallenged authority. If not for the voyeuristic nudity, you might call her image feminist.

But then there’s the roofied girl, a depiction of abject weakness, the pose reducing her to a faceless and defenseless torso. The Queen’s power is positioned over this lower image, appears somehow predicated on it. While her impersonal eyes assess her ghouls, her imperial foot pins the unconscious girl’s hair. She is literally standing on her.

There’s a range of unstated narrative possibilities–does the Queen maintain power by sacrificing her Caucasian sisters to the dark horde? are only skinless and so racially unidentifiable ghouls allowed to fondle white flesh?–but the pose says enough. The girl is the Queen’s victim, not the other monsters’.

Why was my skeleton hand drawn to the unconscious girl’s breasts, but not the Queen’s? They’re smaller, so less intimidating? The Queen is equally exposed, but wholly in control of the fact. I can ogle her, but only because she seems to permit it, her chin angled invitingly away. But at any moment, those eyes could turn and gaze back at me. Did my seven-year-old bones inch across the roofied girl’s ribs because she has no eyes to see me? Did my memory fabricate a throne because a seated Queen is less horrifying?

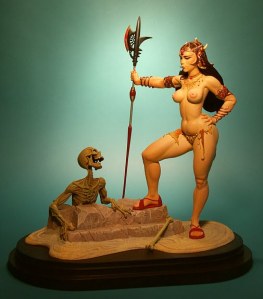

Apparently Tim Bruckner was uncomfortable with these questions too. When he adapted “Ghoul Queen” into a 3-D miniature, he altered more than two dimensions. “It was important to pare down the composition to its essentials,” he said.

Non-essentials include ghoulish racism, slithering homophobia, and date-rape misogyny. But the skeleton remains–though not the nature of its now non-predatory hunger. “There’s nothing coy or retiring about a Frazetta woman,” explained Bruckner. “Even simply standing with a pike, her hand on her hip, being admired by one of the undead, she announces her presence with every sensuous curve of her body.” Bruckner literally turns my skull’s desire toward a stance of female power.

But I still wouldn’t choose the revised Ghoul Queen for my cover art. National Lampoon dubbed their issue “Strange Beliefs,” a better title for the painting too, though I doubt the editors knew they were lampooning American sex and racial norms. They presumably didn’t know they were lampooning me.