Trigger Warning: This article talks about sexual assault and rape, at length. In an attempt to reduce inadvertent exposure to the material discussed, I will provide links to specific sequences.

_______

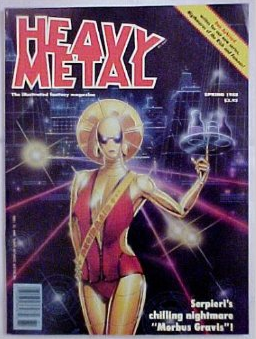

In 1986, Heavy Metal changed their format from monthly to quarterly. As part of this format change, they began to print full stories instead of serializing them. Mostly, these stories were originally printed in Europe – where the Francophone market published 48 page collected editions called albums.

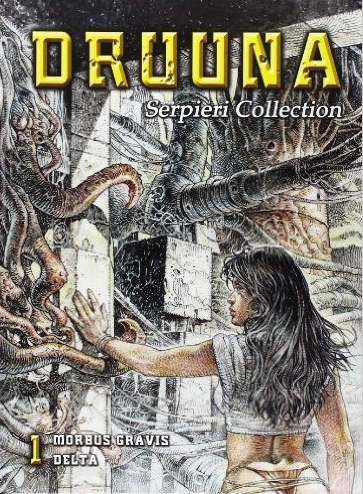

The third full album printed in the new quarterly format was Morbus Gravis (Severe Disease) by Paolo Eleuteri Serpieri, in the Summer 1986 issue. This feature introduced Druuna, a sexually charged woman navigating her way through a nightmarish dystopic society with nothing but her wits and her sexual availability to keep her alive. Over the course of the story, she is forced to expose herself, prostitutes herself for medicine, and is forced to perform fellatio at knifepoint. In retrospect, this was tame.

In spite of (or, perhaps, because of) this appalling level of sexual violence, Serpieri (and Druuna, especially) became massively popular among the Heavy Metal readership. So much so that a parody strip was published asking the question “Where is Druuna now?” (Answer: married, with two kids.)

The appeal was not and is not difficult to understand. Serpieri is a master craftsman. From the various sketchbooks that have been published, it is obvious that he enjoys drawing women. Naked women. Sexy women. And because he enjoys drawing them, he has gotten really good at it.

Any casual connoisseur of pornography can tell you that the act of sexual intercourse is not inherently anything – visually sexy, meaningful, or even necessarily pleasurable. It’s the elements that make up the context of the act that add significance. Even something as simple as bad lighting or poor framing can push a visual depiction towards embarrassing or arousing.

Making something look sexy is not an easy feat. Serpieri knows this and the amount of effort he puts into his work is obvious. He is an incredibly talented illustrator who also happens to have a very good grasp of sequential narrative. That he likes to use those talents to draw people having sex would seem like a net positive – until you realize that a lot of the sexual activity is non-consensual. But he has somehow managed to draw the assault as sexy, which makes the realization very uncomfortable when it hits.

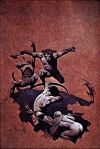

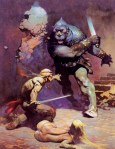

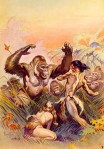

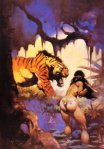

Serpieri works best as a pin-up illustrator, creating one off images that are designed to titillate and arouse the viewer. These are, to a one, perfectly suited to do just that. There is no problematic text to distract from the purity of the visual depiction. Which feels like an argument for the platonic ideal of looking at women without talking to them, so as not to spoil the illusion, but there you go.

To be sure, there is a straw-man argument to be made (half-hearted at best – like you’d find from a certain kind of Twitter account holder, one who doesn’t like to be challenged on his enjoyment of problematic entertainment) that the story is set in a dystopic future where survival of the fittest is the rule and depicting sexual violence is both natural and understandable. After all, that’s what happens when society collapses and there is no means of enforcing mores like consent. Sure, but it is really necessary to depict it so much? And if society has to collapse for these kinds of things to be normalized, why does rape still occur in this day and age?

Serpieri himself claims that Druuna’s approach to sexual pleasures is actually a challenge to Judeo-Christian mores on sexuality. Which would be laudable if there wasn’t quite so much rape. And it’s not like Serpieri is unable to depict healthy, consensual sexual situations. He is. He just choses not to, for reasons.

To be clear – Heavy Metal had a long history of problematic stories. Sexual assault and rape are not the sole province of Serpieri. And he was not the first artist to produce beautifully rendered, overly sexualized science fiction that didn’t make much sense (I’m looking in your direction, Fernando Fernandez). However, to the extent that Druuna became emblematic of Heavy Metal as a publication, she also became emblematic of the sexual assault problems at the heart of the most problematic stories published by that magazine.

—————————————

In the Spring 1988 issue, Heavy Metal published a follow up Druuna story. In this story, Druuna is only raped once – by someone she knows and was actively fooling around with before he brutally and suddenly crossed the line into non-consent (page 42). About the best I can say is that it’s a very realistic example of a date-rape scenario. The sequence to that point is incredibly erotic, but subsequent rereads retroactively taint any potential for arousal.

In the Spring 1988 issue, Heavy Metal published a follow up Druuna story. In this story, Druuna is only raped once – by someone she knows and was actively fooling around with before he brutally and suddenly crossed the line into non-consent (page 42). About the best I can say is that it’s a very realistic example of a date-rape scenario. The sequence to that point is incredibly erotic, but subsequent rereads retroactively taint any potential for arousal.

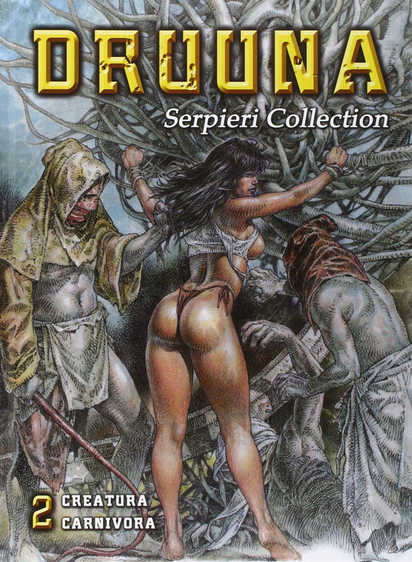

The real sexual violence in the story is reserved for Hale – a woman that Druuna meets in the wilderness. Shortly after they meet, Hale’s father is killed by a group of soldiers. One of those soldiers immediately rapes Hale and takes her as his possession. The most disturbing part of this is the panel where we see Druuna and one of the soldiers standing by passively while we can read the off-panel dialog of Hale screaming “no” and being ignored (page 23). The page turn shows the actual rape in progress. As a piece of sequential storytelling, it’s very well executed. Both the reaction shot and the actual rape are excellent example of show, don’t tell. But that’s about all it has going for it. That and the heartbreaking shot of Hale wrapped around herself post-trauma.

Druuna’s advice to Hale is to just let it happen (!) because whatever the soldiers can do to them can’t be worse than the monstrous mutants who wander the wastelands could do instead. Survival is the key, and the best advice is to endure. Which is an interesting thing for a young, impressionable young man – a demographic that was reading Heavy Metal at the time – to read. Especially so close to such a graphic sexual assault.

Hale is raped a second time, and the act is used to drive the plot. While the soldier is distracted, a mutant comes out of nowhere and drags him away (page 29). Hale is laughing hysterically at her salvation and near-death experience and the death of the soldier is given a little too much dramatic emphasis, considering that he was mid-rape when he was whisked away. Again, Serpieri is a good enough sequential storyteller that we get to see this occur, from the rape onwards.

Completing Hale’s arc, we are shown a single image of her working as a prostitute in a military barracks and we hear nothing more about her for the entire series.

In the Summer 1988 issue of Heavy Metal, an editorial addressed current events. It seems that copies of the previous issue had been seized at the Canadian border for being in violation of code 9956 – a writ denying the importation of material dealing with sex with violence, bondage, etc. The editorial admits there was “sex with violence” in Druuna.

But there is a side of the strip that seems to have been ignored. Beyond the breasts, beyond the sex, there is an extraordinary power within the story – the horror of a world gone mad. We were not condoning the violence, simply presenting a frightening oftentimes exaggerated look into a future even more violent than the times we live in now.

That very issue, they featured a slew of stories from the Spanish version of the Illustrated Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Because they’d been censored, you see. This was a free speech issue.

Heavy Metal has always been a commercially-minded magazine. That approach has worked out very well for them and gave the publication a kind of self-aggrandizing swagger. You knew they were going to be over-the-top and merchandise everything, so nothing came as a surprise after the first five or six years.

Heavy Metal in the late 80s was filled with material by Daniel Torres and Peter Kuper – to the point where they felt like house artists. However, no character captured the public attention like Druuna. The two first books were republished as stand-alone hardback editions, as well as a slew of sketchbooks and other art books. Serpieri reprints became big business for Heavy Metal. So much so that these are all still in print, decades later.

An interesting side effect from the free-speech editorial board was that Heavy Metal began to censor some scenes of sex and violence. The series The Waters of DeadMoon received the most obvious changes, but Serpieri’s later works were given special attention. A few panels were altered, but mostly word balloons were placed at strategic spots to cover penetration, like a modern day da Volterra. In later years, this got to be almost farcical and a bored archivist could spend hours spotting the unnecessary bowdlerizations. In one later story, an entire six page sex scene disappeared, leaving readers confused.

Ironically, there was a note in May of 1992 (the first issue that Kevin Eastman’s name shows up in the masthead as publisher) that read

We have gotten a lot of flack about censorship in the Raoul Fleetfoot story (January 1992). Those little black bars covering up “casual indiscretions” were part of the story and not our way of screwing around with the First Amendment.

Given previous behavior, it would not have been that unlikely a conclusion to arrive at. I certainly came to the same conclusion when I read the story in question.

———————————–

In the November 1992 issue, the third Druuna story, Creatura, was published. Infamously, this story contains a four page sequence (pages 45-48) where Druuna is drugged and gang-raped. On the last page of the sequence, she wakes up and the following internal dialog shows up in a thought balloon.

Forgive me, we might have been able to live together. Your little devils gave me so much pleasure, you know? I don’t know how much those drugs were responsible… But I can reassure you it was a wonderful experience.

Which is, in my opinion, the crux of the problem with these stories. If there were no word balloons, it would be entirely possible to read at least one of the pages of the sequence as just a very well-drawn group sex scene, with attendant pornographic associations. It is drawn sexy. That’s how Serpieri draws these things – he’s very good at what he does and his artistic choices are on the page. With the context added in, the juxtaposition of sexy and horrific makes the mind recoil in realization.

However, the apology that the victim utters (even if it’s only in her mind) seems to absolve the instigator of the assault (a woman) retroactively on the theory that it was fun, once Druuna got into it. I cannot think of a more dangerous sentiment to present to the kinds of people that would find those pages more sexually arousing than horrific; keep in mind that I count myself as one of those individuals.

The first Druuna story was published in 1986, the year I entered high school. Heavy Metal was not news to me – on the contrary, my father had the complete run as I was growing up, so there was not a time when I did not know that Heavy Metal existed. But the perfect bound quarterly issues starting in 1986 did not fit into the official commemorative binders that held the first nine years of the publication. The new issues sat alone and were easier to consume as they came in.

The second story was published when I was still in high school and Creatura came out when I was living at home, having dropped out of college. In those pre-internet days, anything pornographic was a precious item and this one was mailed directly to my house. I’ll spare you the gory details, but I honestly wonder how much those three stories impacted my sexual development.

If you can read Marain, figuring out my FetLife profile shouldn’t be that difficult. I’m not going to make it easy for you, but I will say that enthusiastic consent is a massive turn-on for me. And even the slightest hint of reluctance makes me very uncomfortable. I guess that means I got the right message? It’s difficult to say for sure if I am representative of the average reader reaction or an outlier.

I will say this, though – I tend to be attracted to women with bodies that are similar to Druuna’s and that’s probably not a coincidence.

—————————————

Five additional Druuna stories were published between 1993 and 2003 (fun fact: more Druuna stories were published under Kevin Eastman as publisher than not), but I’m not going to recap them all in nauseating detail. They all are all set in more or less the same technorganic futuristic hellscape, a place full of horny soldiers, brutal authoritarianism, sadistic sexual predators, disease, ravenous mutants, and bewildering recurring characters.

There is a lot of philosophy and soul-searching. Consensual sex is found throughout the series, but usually only in the context of idyllic dream sequences that serve to demonstrate what the world could be like. On the other hand, the constant threat of violence and sexual assault seem to serve as a cautionary element, describing how the world is messed up.

Which works, on an allegorical level. But the stories themselves tend to duck and weave considerably around the outright identification of self-identification as allegories. In fact, Serpieri’s hyper-realistic artwork tends to work against reading these stories as allegorical. These are specific events, happening to specific people.

If Druuna is, indeed, some kind of ur-woman, what do her repeated sexual assaults mean, exactly? Are they meant to imply something about the universal condition of women? That’s pretty bleak, no matter how you turn the interpretation. However, if there is no meaning to these assaults, then the allegory argument falls apart on first principles.

It is entirely possible that I think too much about these things.

—————————————

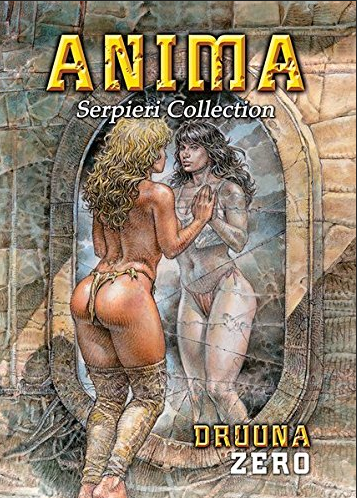

One final story: When I was in a mall outside of Antwerp earlier this year, I was flipping through Anima, the first new Serpieri book in thirteen years, at FNAC. My girlfriend looked over my shoulder and noted that the book was not just “a little rapey” (as I had described his work in Heavy Metal) but depicted actual rape, complete with knives to throats during intercourse. Considering that the book is largely silent, this is both a testament to his sequential art capabilities and his pre-occupation with sexual assault.

Paolo, you’ve still got it!