On Superman: American Alien #1-6 (of 7) by Max Landis (writer), Nick Dragotta, Tommy Lee Edwards, Joelle Jones, Jae Lee, Francis Manapul, and Jonathan Case

“American Alien is the Best Superman Story In Ages” Evan Narcisse, Kotaku

“Max Landis is still batting a thousand with this Superman mini-series.” Jesse Schedeen, IGN

“Landis’ journey through Superman’s formative years aren’t just a love letter to a hero, but to the people who read him as well.” Richard Gray, Newsrama

“Superman: American Alien #6 is another strong installment in one of the best Superman stories published in quite a while…We’re six-for-six now, and all parties involved should be proud of what they’re delivering.” Greg McElhatton, CBR

“Superman doesn’t, to me, doesn’t exist — it’s just Clark in a costume choosing to try to help people…My comic…It’s just about how Clark Kent became Clark Kent.” Max Landis, Newsrama

“…a self-indulgent, derivative dumpster fire that borders on Smallville fan fiction…[…]…There are two different writers running around in the industry named Max Landis. The first one is the brilliant albeit intolerable douche who wrote Chronicle…The other one is the self indulgent man child who writes this good looking, visually charming drivel.” Oz Longworth, Black Nerd Problems

__________________________

My first impression on reading Superman: American Alien was that it seemed like a decently written television series. The kind you might find on a small cable channel littered with demographically targeted YA themes about young powerful people grappling with their powers.

The characters seemed like they were speaking normal American-style English as opposed to the curt expository superhero-ese of the average DC and Marvel comic. The writer appeared to have a firm grasp of the intertwining relationships of the DC universe with Oliver Queen and Bruce Wayne mixing it up with Clark Kent in encounters which delineate their motivations.

There’s little doubt that it’s a better comic structurally speaking than the new Black Panther. Max Landis has a better sense of how to fashion a story and to entice readers into his world. When Clark gets saved by a pair of Green Lanterns after trying to breach Earth’s atmosphere for the first time in issue 6, you don’t need to know how they fit into DC continuity or even who Abin Sur is. The continuity helps of course, but at that point, Clark just needs to see some extraterrestrials. And if you don’t know who the Green Lanterns are, then so much the better. If only every superhero comic reader could be faced with something new every time he opens a comics pamphlet.

I didn’t realize until after finishing issue 6 that American Alien was written by a semi-famous screenwriter—a familiar name which had come up in recent weeks because of some mildly ignorant comments concerning whitewashing in the new Ghost in the Shell movie (since vaguely retracted I understand). And just in case you’re wondering, it’s a really, really white world out there in the world of American Alien, and not just in Kansas. Save for the moment when Jae Lee takes over the art chores and everyone suddenly transforms into an East Asian, I count a black Jimmy Olsen as the only significant non-white cameo in the plot (he stays a bit longer on TV’s Supergirl).

You would think a DC comic with a conspicuous title like “American Alien” would attempt to address some of the issues surrounding the word “alien” in our immigration straitened times but as with the rest of the comic, the title is just a guileless play on words; Landis’ Superman is an alien less the controversy.

As with various other iterations of the Superman myth, the “alien-ness” that Clark Kent has to deal with amounts to navigating his superpowers, fine tuning his mission in Metropolis and coping with city life. Can you imagine what it would be like if music today was essentially a facsimile of the music of the Beatles and Rolling Stones? Well, look no further than one of the most acclaimed superhero titles of 2015-2016.

Of course, under any normal circumstances, the ability to write a Superman story based on time-tested elements and archetypal characters in the DC universe would be part of the basic toolkit of the average comics writer. But a small survey of the titles coming out each month should attest to the fact that the majority of these titles are in fact illiterate. Landis’ chief accomplishment as a writer is that the characters peopling his 6 issues (of 7 so far) seem to have the mannerisms and speech patterns of normal human beings. This isn’t the work of Eugene O’Neill or even his cut-rate twin, Louis CK, but it’s more than enough to make the average critic sputter in delight.

American Alien is laced with a familiar, anodyne nostalgia for a America that never was and which most Americans probably haven’t experienced at any point in their lives except through reruns of It’s a Wonderful Life and Little House on the Prairie. The only sweat and tears here are those experienced when Clark learns how to fly. Farming is boring. You can imagine everything being shot at magic hour like Nestor Alemendros’ work on Days of Heaven less the locusts, fires, and infidelity.

The pain in American Alien isn’t real—it’s meant to be beautiful; the kind of “pain” you want to remember for the rest of your life. The kind of pain that teaches you how wonderful and meaningful life is; the sorrow which makes you a better person. Smallville is the kind of place where morphine cabinets are left unlocked and undisturbed, an utterly denervated, virginal landscape.

Frankly, I’ve had enough heartwarming stories about Smallville to last me a lifetime though it’s clear that Superman devotees are a bottomless pit when it comes to this material. The Arcadian countryside of waving corn fields, understanding neighbors and crop dusters; here regurgitated once again but less the mastery for nostalgia seen in Dave Stevens’ The Rocketeer with nary a Betty in sight.

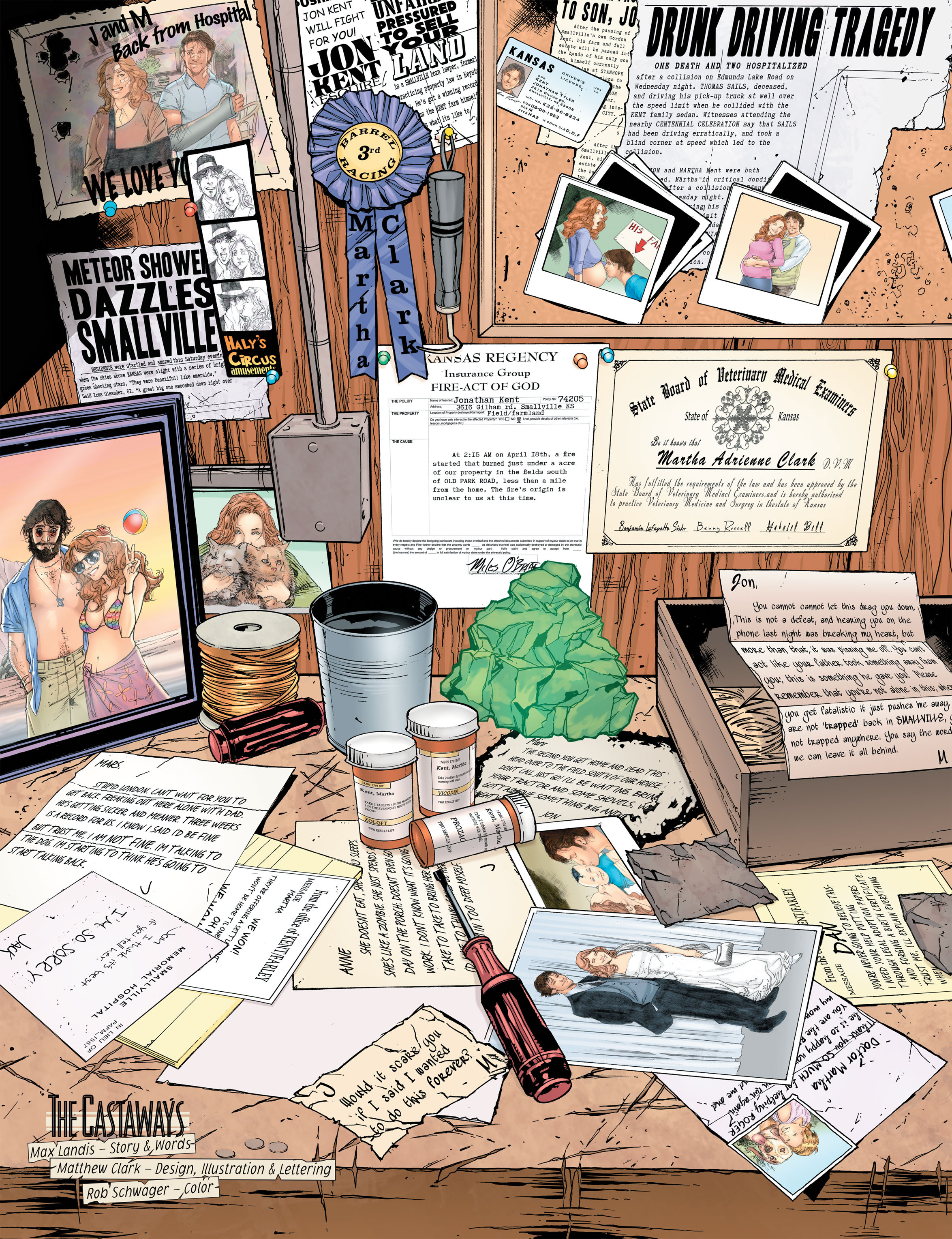

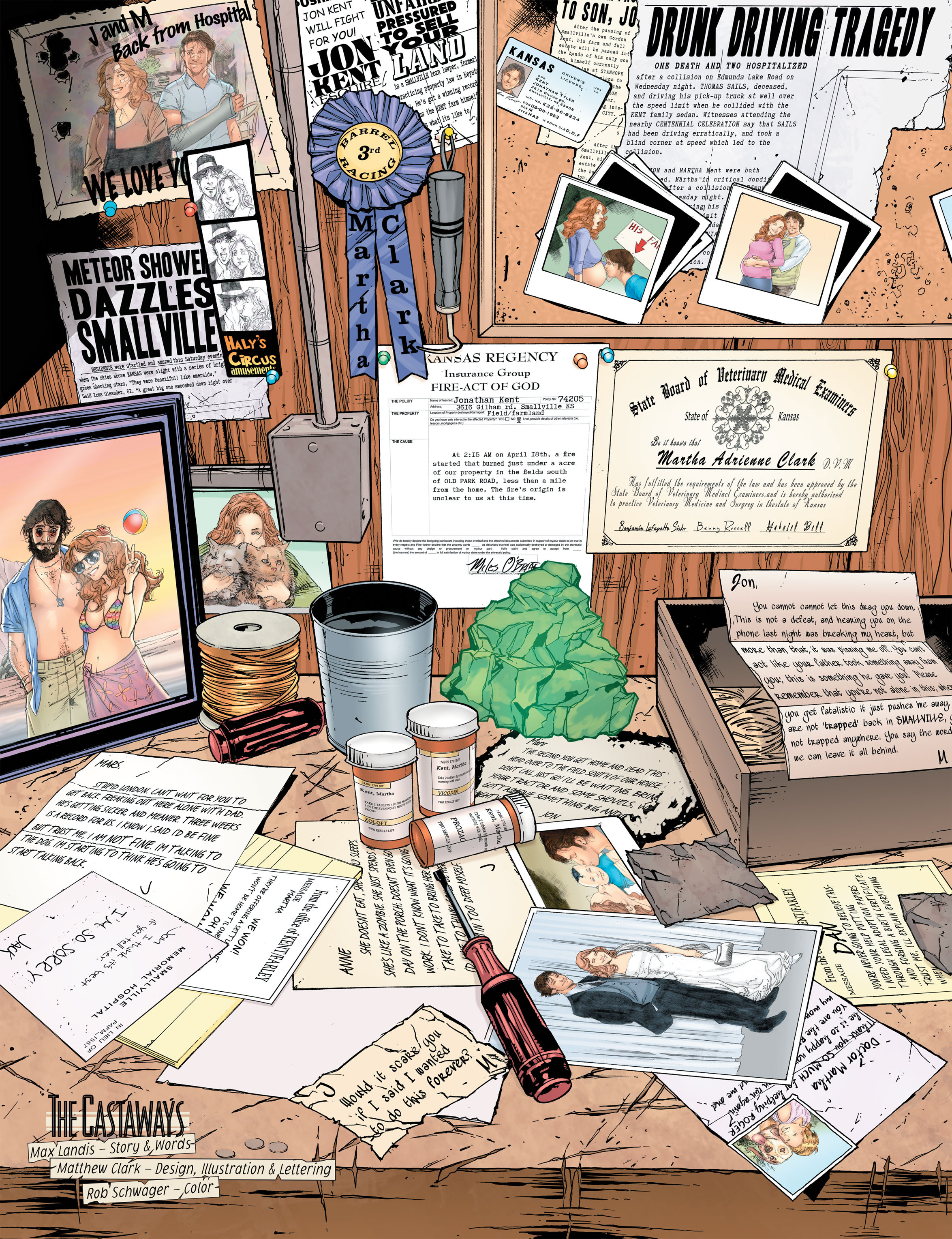

The entire bitter sweet history of the Kents recounted in the single page “The Castaways” is meant to mitigate this.

We have the college (?) sweethearts, a baby lost in a car accident, the depression (Prozac, Zoloft), the disastrous farm fire (an act of God) resulting from Clark’s arrival, the adoption, the noble professions in service of those less fortunate (she’s a vet, he’s a lawyer looking after the rights of the small and downtrodden). Partially told in epistolic form, you can see that it’s a half-hearted stew; the family memories strewn across a work shelf with lettering so uniform and done with such clarity of purpose that we instinctively know to care very little for these faux reminiscences of cardboard constructs.

Oh, there’s some violent murder in issue 2 when some villains rob a grocery store and nonchalantly knock off some insignificant classmates of Clark and his pals. We don’t know who they are but the dialogue deigns to tell us that they are of some consequence to the protagonists. You’d get more of a reaction by killing some puppies in print I think.

When Clark blasts off the murderer’s arms accidentally with his heat vision, it’s a comeuppance, not a real moment of horror. The violence is idyllic; accidental but noble, and judicially satisfying like I assume justice is in general in the United States. The Metropolis of American Alien is straight out of the child friendly era of Curt Swan et al. with polished streets, well scrubbed citizenry, playful billionaires and general happiness apart from the odd experiment gone wrong.

There is a streak of banality in the proceedings but the negative repercussions on the comic’s aesthetics are minor if only because it’s all too familiar. The superhero plane of existence is choked with unlived worlds, social blindness, and general self-centeredness; a genre seemingly tailor-made by Tony Robbins brimming with tales of self-fulfillment and self-actualization.

Alan Moore’s Miracleman was a real world reimagining of these themes and was choked with brutality and significant amounts of collateral damage—the pure arrogance and carelessness of power. This was once seen as a necessary corrective in the revisionist 80s but is now viewed as a stultifying and corrupt path for the genre. Grant Morrison’s All Star Superman tried to find the middle ground. If his Kryptonian gospel envisions Kal-El as the risen Christ it is because he is supposed to be an amalgam of absolute power and absolute good. The series is a hagiography, a religious undertaking, the euangélion after Siegel and Shuster,

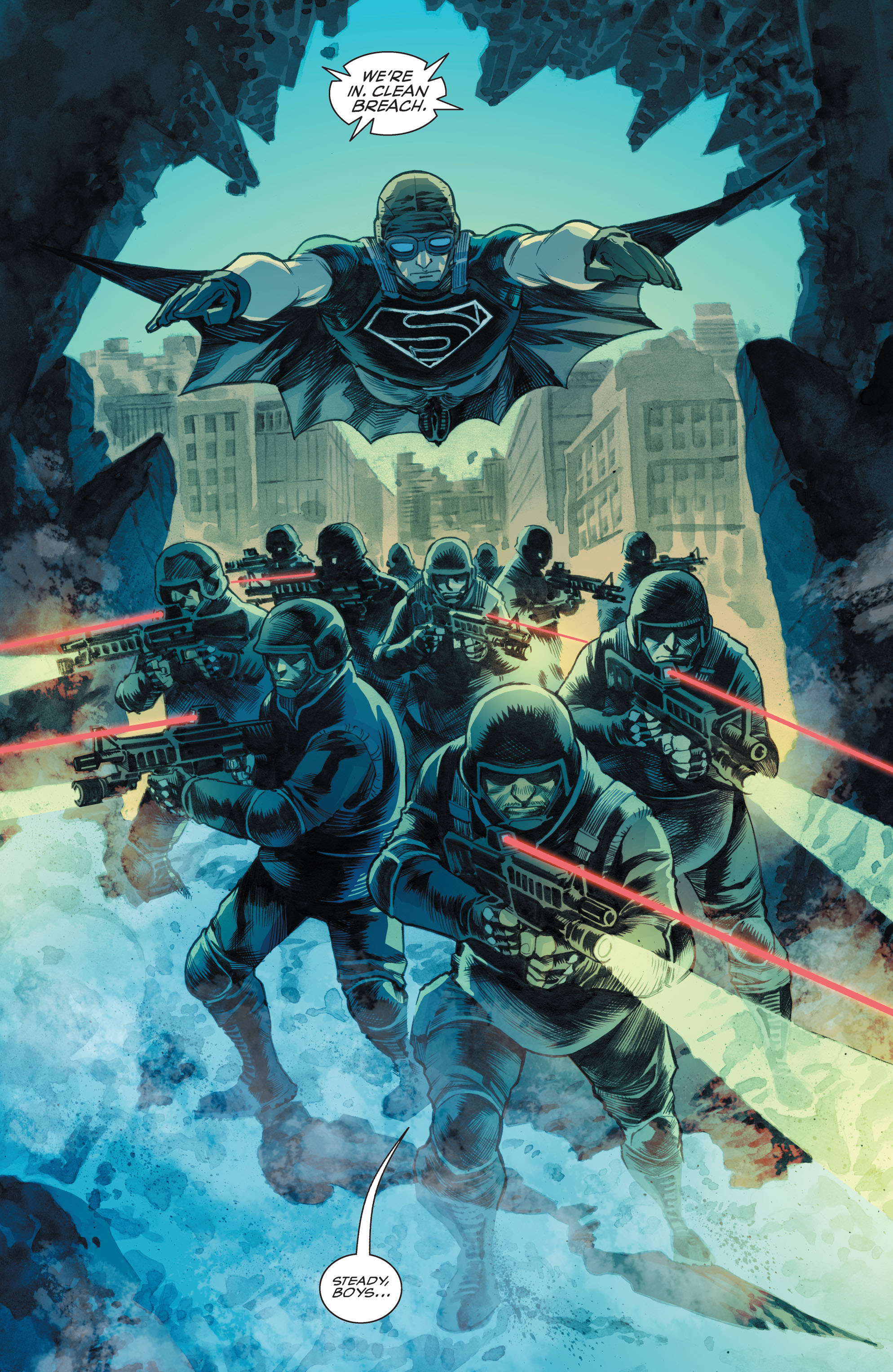

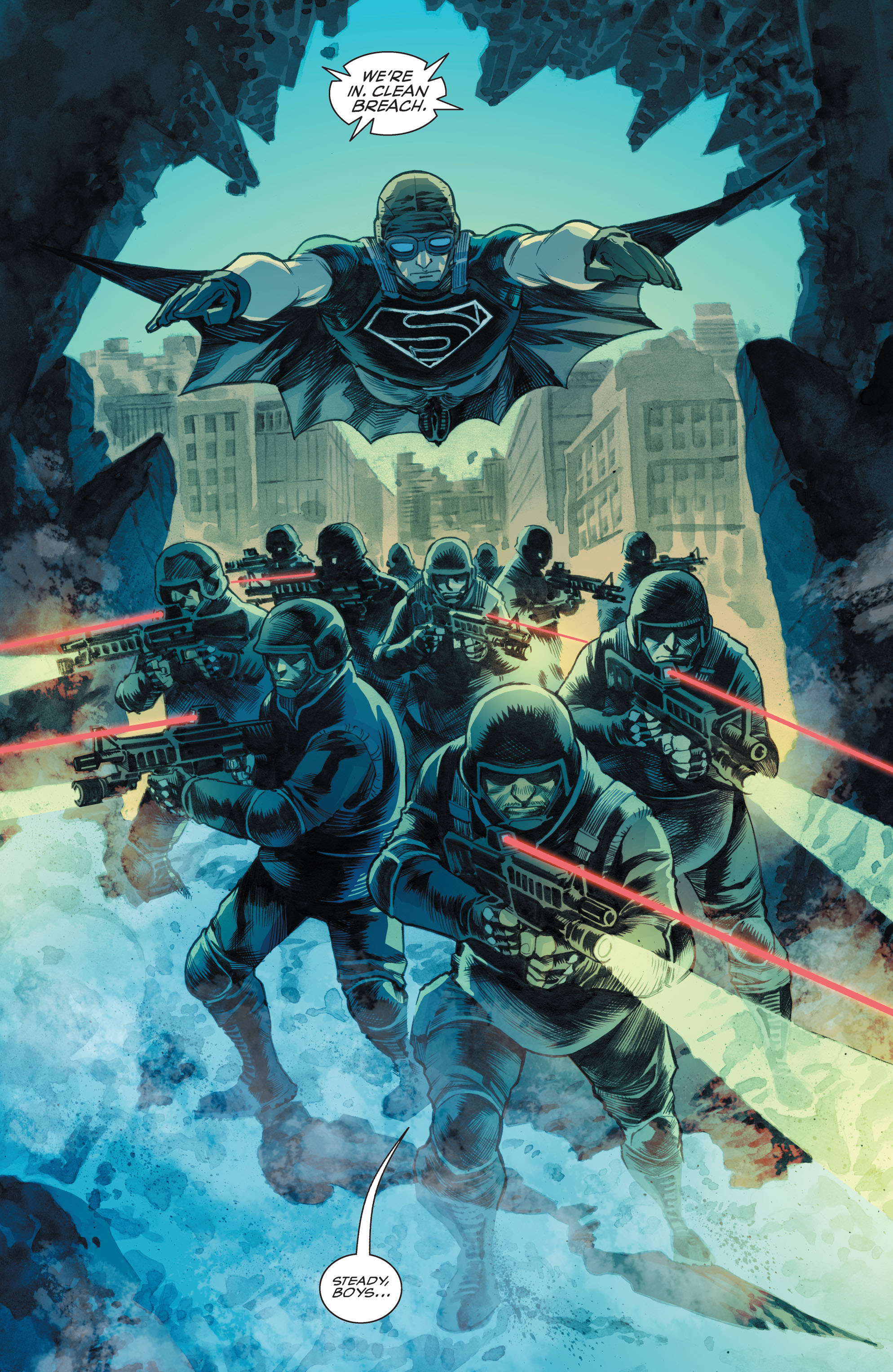

Landis’ Superman is meant to be an everyman; a slightly underpowered Smallville Clark; the kind of person modern day readers expect Superman to be—an idealization of human power and its application. Nowhere is this better seen than in issue 5 of American Alien where Superman flys into combat with a tac team of heavily armored policemen (or maybe National Guardsmen) with assault rifles and laser scopes to fend off a monstrous human experiment created by Lex Luthor (they didn’t have the budget for an Abrams tank).

In Miller’s paramilitary fantasy of The Dark Knight Returns, Superman is part of the problem. Here he’s part of the solution, joining a flying squad armed with M4s; the “eagle” protecting American soil and integrity. There’s no irony at work here—this is America the beautiful in all its military might and machismo, like a giant phallus breaching a crevice, standing ready to rape the world.

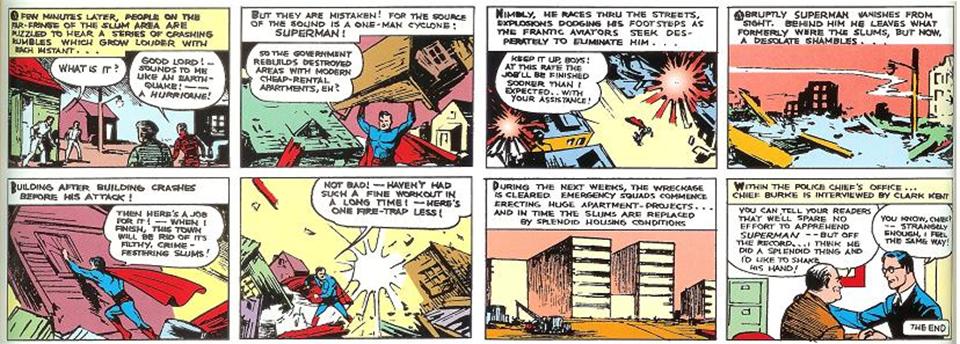

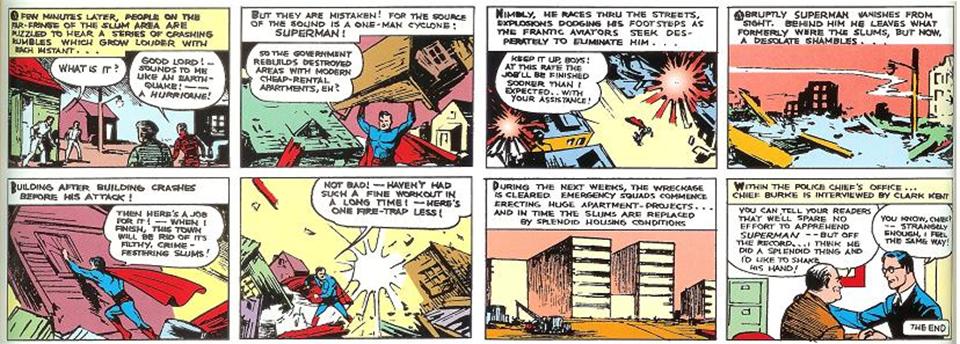

And maybe this is how it always meant to be. In one of the greatest Superman stories ever told (“Superman in the Slums” from Action #8), the Champion of the Oppressed has to find a solution for the delinquents who have been cast into their criminal ways by the slums they live in. His solution is to turn into a living cyclone, destroying the slums so that “the government rebuilds destroyed areas with modern cheap-rental apartments.” Not even heavily armed troops and a fleet of bombers can stop this Social Anarchist (who seemed to have an odd faith in the powers that be to clean up after him).

In the penultimate panel of the story, an emergency squad erects huge apartment blocks (without the help of the caped one I should add). The Superman of Siegel and Shuster didn’t have time for laying bricks but saw himself as a destructive force of nature, the hand of divine justice. If he destroyed your home and slapped you around, he was doing it for your own good. In Landis’ version of Superman the purity remains without the social mission; the destructive frenzy held in check by the author’s pen; the fairy tale fascism allowing us to sleep soundly and comfortably in the innocence of our human power.