The following expulsion relates to a Twitter conversation into which I rudely inserted myself earlier this week, concerning the mission of certain websites in publishing writing on comics, and the character of certain tendencies in comics criticism. I was then offered one million dollars to expand on those tweets here. I’ll be checking the usual address for payment, Noah!

***

Years ago, when I was younger, I started a blog about comics because I wanted to be part of a conversation, and I found the message boards to be slanted toward rock star frequent posters, all of whom should have been me. It takes some measure of self-regard to presume that anybody would want to read your words on a topic in the absence of solicitation, and I found it rightly cheering and worthwhile to control my little island of dictation and catch the occasional seagull-bound dispatch from neighboring personal nation-states. At that time, you could identify most of the writers-on-comics-online from a generous sidebar listing, and — if you were oversensitive, which is to say you were blogging — you felt the need to respond to basically everything of probable interest that was ever said, or occasionally just implied.

Gradually, the scene became large enough that it was less a consortium of islands than a small city, and in a city you lack the psychological compulsion to acknowledge every dress outlet and cheese shop simply because they are there. I became no less self-interested, but the primacy of conversation became subsumed into the fascinations of communication: argumentative craft, writerly noodling. Of course, I had to be careful in some ways, as I was aware that I had a small audience, and also that the parity of linkage afforded by the meme-prone internet kept a momentary larger audience perpetually on the horizon. I became aware, silently, of how much I could write before I’d safely assume I was boring people. Today, I think I was too generous in that estimation, but I am not the same person, and neither are you.

Always I knew I would be my editor. That I would self-censor for the good of the communication. I had editors at The Comics Journal too, which I expected, of course, from a print publication. With apologies, I confess that the editors I encountered through online group sites were thought of as gatekeepers, yes — as homeowners and hosts, as sounding boards and error-catchers — but not as forces behind the craftwork of identity online. I would be me, on any site that would have me.

Eventually, though, there came a time when individual blogging faced the same perils of noise as message boards. This was inevitable, given the volume of free, equidistant writing online – given the choice of two types of apples, the consumer will exercise some informed judgment, but given the choice of two hundred they will stick to what they know. The illusion of permanence and the glamor of size became crucial. I don’t know anybody who reads Ain’t it Cool News anymore, but by god it’s still around.

This was the age of aggregation, and I went willingly. A certain publication I’d contributed to twice invited me to write for their online edition. In the future, some would place Comics Comics toward the front of a small movement to construct counter-histories of comics evolution; whether the chicken of this departed forum preceded or followed the egg of Dan Nadel’s Art Out of Time and other publications is a matter for future and no doubt highly exciting controversies. At the time, I did become aware of a reputation existing for the “Comics Comics gang,” which I never felt encompassed the attitudes of everyone on the site, but fuck it – I’d always appreciated history, and history’s manufacture, and comics’ tendency to forget all but the most victorious of popular winners. It was once said that the readership comic books departed every five years to make way for new, young readers devoid of expectations; that’s not true of comics, but it seems right for histories thereof.

But Manny Farber convinced me, in my arrogance, that I ought to be a termite, and burrow my way into the neglected crevices of the culture. That wasn’t what Farber meant by his essay, admittedly, but I was too busy reading comic books. Lots and lots of comic books, more than I could ever possibly write about, particularly after I graduated school and found a day job and stopped posting seven days a week, as I had done for years. I loved many of the ‘established’ classics. I still dearly love Chris Ware. But even in the diminished state of comics criticism — the truest and most damning thing about which I’d ever heard was from the critic Ng Suat Tong, who told me that prose books, as periphery as they are to the popular culture, could always count on several and varied reviews of the bigger releases, while comics cannot — certain vaunted works do attract a goodly amount of continuous reaction, while too many others join the congress of orphans shivering in dank and yellowed longboxes in Donnie’s Dojo and Sports Collectables, thirteen miles from the state line.

When I could not find things about a comic online, the compulsion rose. What I could not read, I would want to write. I would abandon 6,000 words on Building Stories without much regret, seeing the writing that was out, but a stray back issue of Métal Hurlant would have me rising at 2:00 on a work morning to delineate the gaps in the common understanding of what that magazine represented.

Alas, I understood then that I am as much a character as an author.

The aggregation of voices online inevitably subsumes the individual into the common understanding of the forum’s inclination. This was made plain as scalding water when Comics Comics fused itself onto The Comics Journal and became its online edition. Many Journal writers were retained, as was the Journal‘s name and reputation, and Comics Comics verily ceased as a going concern, both ‘physically’ and rhetorically. The editors were thrust into dialogue with the expectations of the one comics magazine that would span the whole of the history of the comic book direct market.

Personally, I formulated a whoppingly pretentious concept for the new releases checklist column I’d carry over from Comics Comics: half would be a reflection on something I’d read very recently, while the other half would make brisk assumptions about things imminently due. THIS WEEK IN COMICS!, in both the retrospective (THIS past WEEK) and prospective (THIS coming WEEK). Additionally, it would allow me to retain a certain seat-of-the-pants, blog-like character I’d come to prefer in composing frequent writing.

But there was a difference. This was not a blog.

And I found myself grateful to be able to exercise such stylistic discretion without the burden of editorship.

It is said, occasionally, that the criticism dedicated to new, young, experimental comics is meager; I don’t disagree. Nor do I disagree that some critics seek the obliteration of the prior canon, and the ripping down of the old heroes. Sometimes I rip a few scraps myself, but my mission, oh god, is individual engagement with works. I realize, though, that I’m on the internet, and that I cannot be exactly an individual anymore; we are all part of sites, of movement, of Ideas. To post on the Hooded Utilitarian is, in part, to be seen through the prism of things Noah Berlatsky wrote in the mid-’00s, often about Art Spiegelman. To write about Heavy Metal is to participate, in part, in a devaluation of the prominence of accepted ‘good’ works, because they are just that less prominent. If Heavy Metal is seen as a misogynistic enterprise, you are part of that misogyny. If the Hooded Utilitarian is seen as a negative force in comics criticism, you are a party to negativity.

This too is history’s manufacture.

Yet if I don’t write about these things… who the fuck will, he screamed, sweating at a mirror, fists clenched, the hero, trying to watch his own back. The function of a critic, he knows, can be to establish or demolish canon, or to theorize on the form, synthesizing the thinking of past experts, applying rigor and distinction as to worth, as to societal narrative, as to moral concern. He thinks, sometimes, that he needs a critic to explain to him exactly what the fuck he is doing, but still –

I am disinterested in formulating mortal [k]ombat between comics canons. That I tend to write about dodgy French gloss porn is not a deliberate statement on the superiority of (say) Heavy Metal to (say) RAW. Rather, it is a (knowing) effort to explore areas of interest to me that otherwise will receive little sustained attention. If I want to say that a work or a tradition is garbage, I will say exactly that, by name, individually. The resultant state of any online venues ‘advocating’ one tradition over another by dint of published writing is an editorial concern. I am not an editor. I’m grateful for editors! It is a bias of my own to focus on works of little demonstrated critical value. Perhaps I’m a narcissist. Nonetheless, I am convinced of the value of this pursuit.

I used to be a libertarian, but then I got old.

[BARTENDER CARDS ME GETTING A BEER]

Fin.

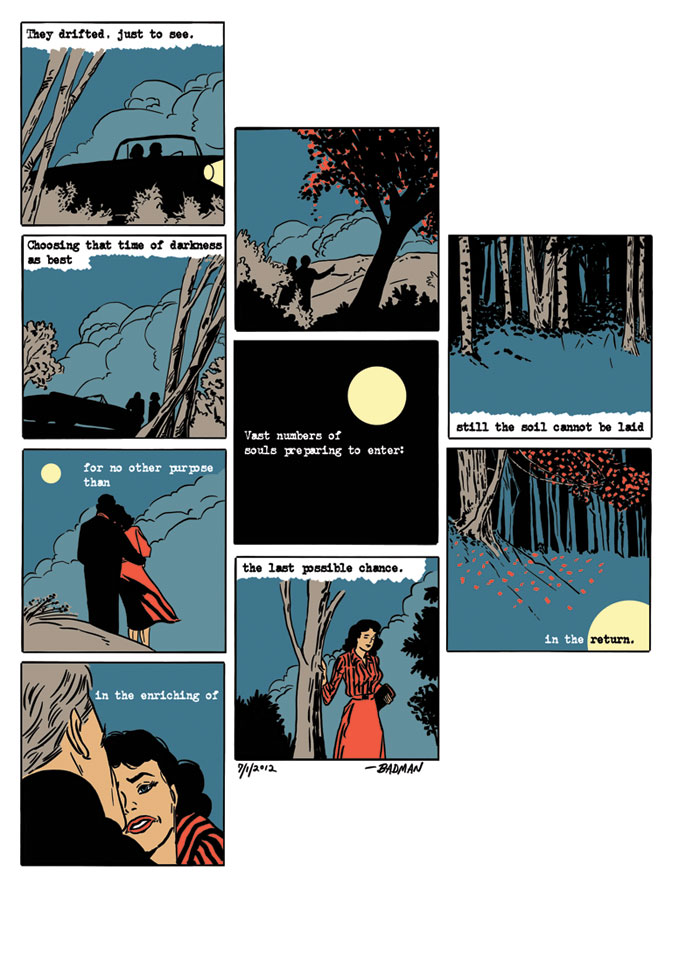

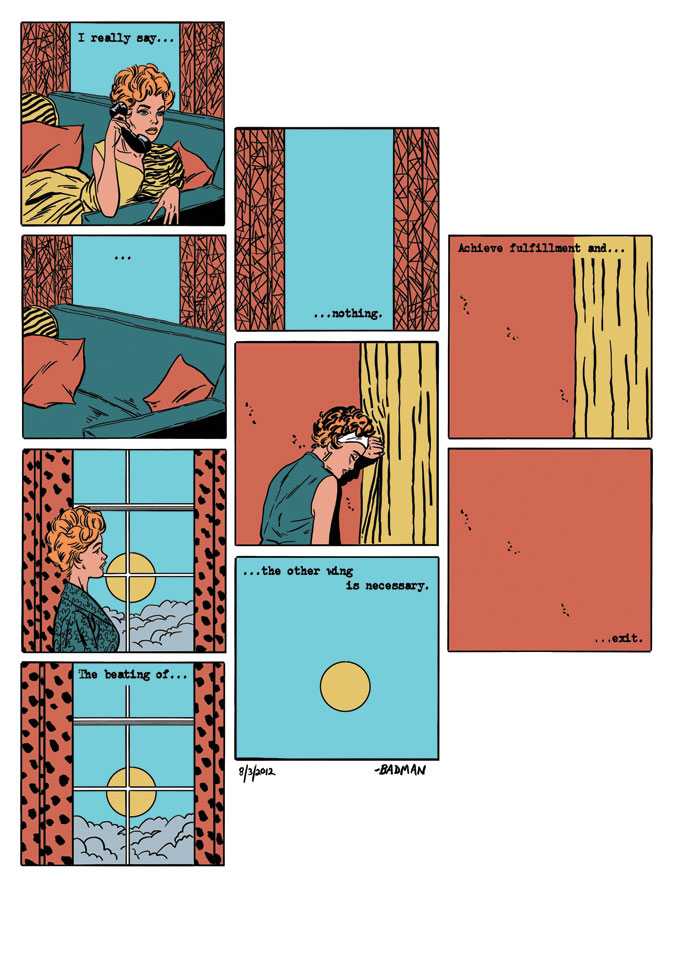

The dead horse from the final page of

Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise,

the greatest work published under the auspices of RAW.