[Those looking for background details and a synopsis of The Heart of Thomas can do no better than to read Jason Thompson’s review.]

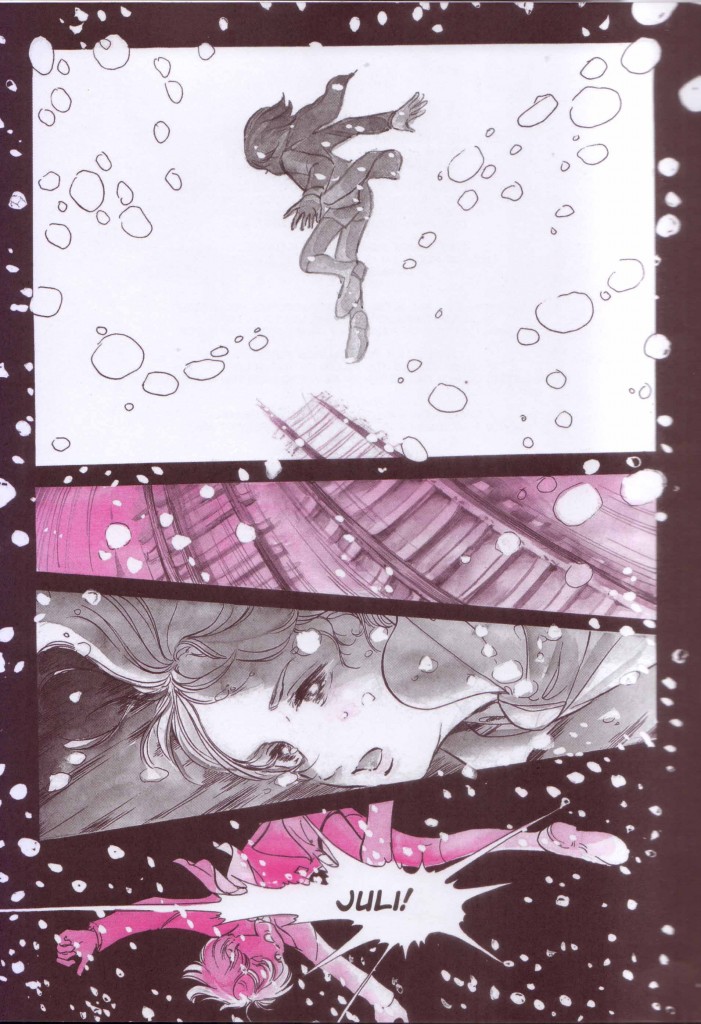

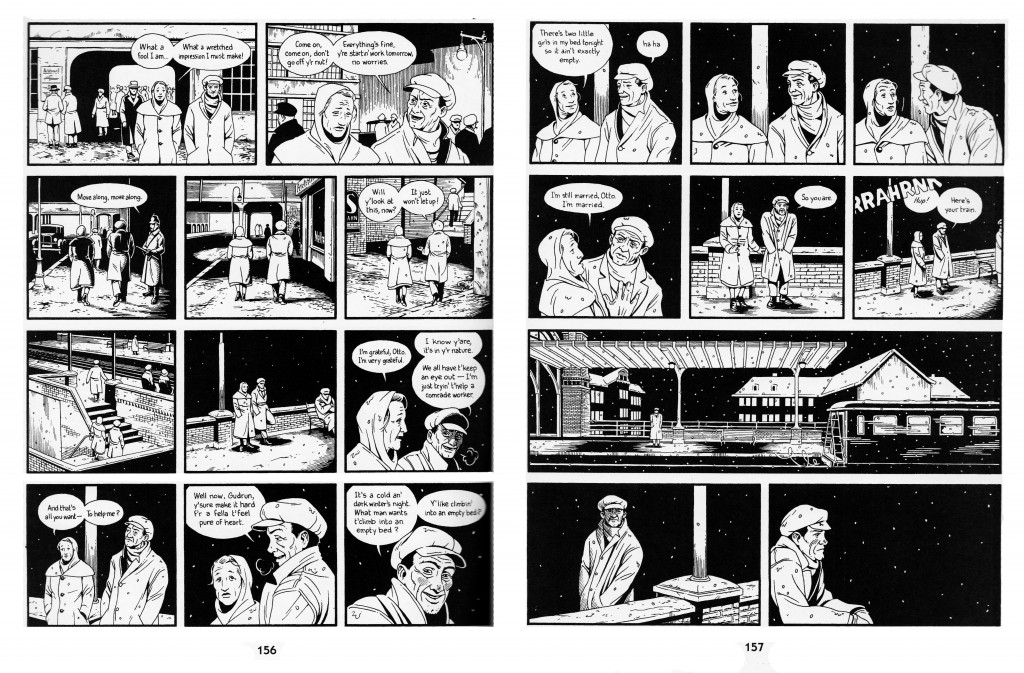

In the opening pages of The Heart of Thomas, the eponymous object of desire and remembrance, Thomas Werner, leaps from a railway bridge to his death.

But who is he? This intangible ghost of doomed naivete crushed by the morass of faithlessness and abandon which has inundated the boarding school which he attends. Perhaps, a metaphor for innocence lost, reborn in the form of his more resilient lookalike, Erich Fruhling—a boy who soon becomes an indelible memory of that life carelessly thrown away; a soul on the path of transmigration in an alien and barbaric Christian world of torment.

Of course, Thomas’ body isn’t subjected to any tragic or tangible mangling despite the suggestion that “his face was crushed.” Death in Hagio’s world is as chaste as the heated embraces and kisses which reach a crescendo towards the closing chapters of the manga. Even Goethe’s Werther (no first name, similar last name) had the presence of mind to die slowly and painfully 12 hours after shooting himself in the head. Mortality is nothing more than a stylized leap into an endless stream of romantic possibilities in Hagio’s manga. Thomas’ suicide is performed out of love for a senior student by the name of Juli, a distant and correct individual who like all suffering, misunderstood heroes, conceals hidden depths of anguish. The appearance of Thomas’ lookalike, Erich, quite early in the tale—strolling past Thomas’ grave as it were—presents Juli and his classmates with a second chance. He is nothing less than an angelic being. Even the school master seems enraptured by this unspoilt youth—like Hadrian lusting after Antinous. One might almost call it a process of deification. And as with his historical counterpart, Erich is subject to both adoration and recriminations. As Hagio asserts at the start of her story:

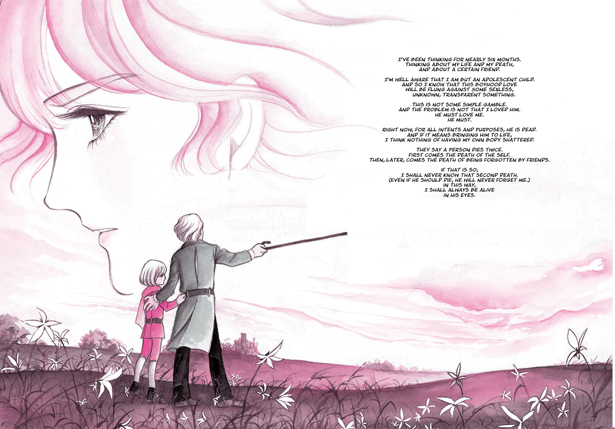

“They say a person dies twice. First comes the death of the self. Then, later, comes the death of being forgotten by friends. If that is so, I shall never know that second death. (Even if he should die, he will never forget me.) In this way, I shall always be alive in his eyes.”

These lines define the authoress’ purpose. The Heart of Thomas rests on a physical manifestation of this remembrance, as florid as a grief stricken emperor’s commerorations of his lover—as if memory had the power to evoke a second incarnation or avatar. Still others might see everything which follows Thomas’suicide as the fantasy of a collapsed mind, the tangled memories and imaginings of a dying brain hoping for a happy corrective to a tragically short life. Certainly, that Germany of the mid-twentieth century imagined by Hagio has no anchor in on our reality. It is an alien planet both to the Japanese and European reader alike—a dream which has no interest in the tradition of Mann, Grass, and Boll but rather adheres to the hysterical breathing, coincidence, and fainting spells of wish fulfillment and hallucination. If these young male students had breasts, they would be ripping their bodices from their angular bodies

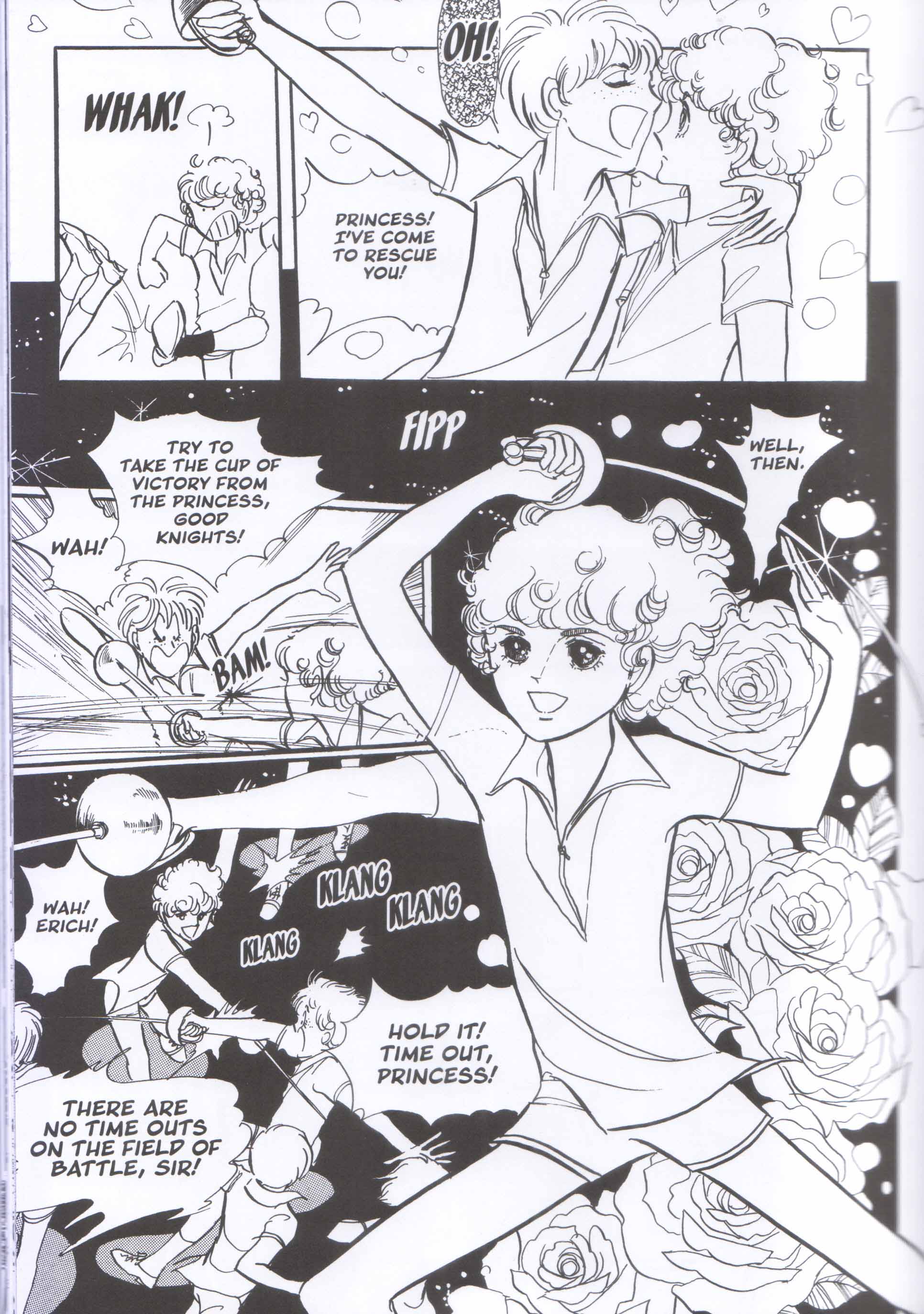

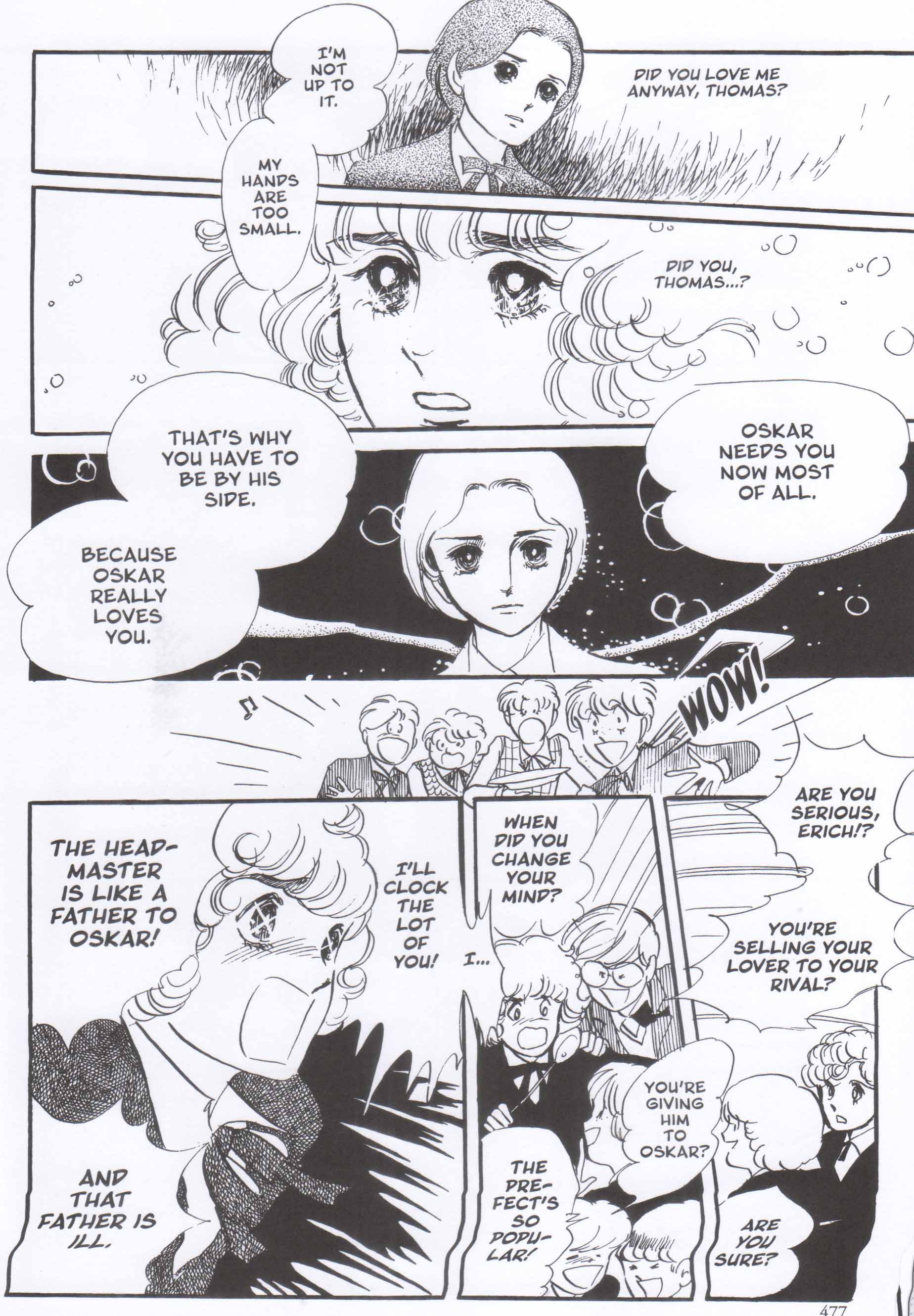

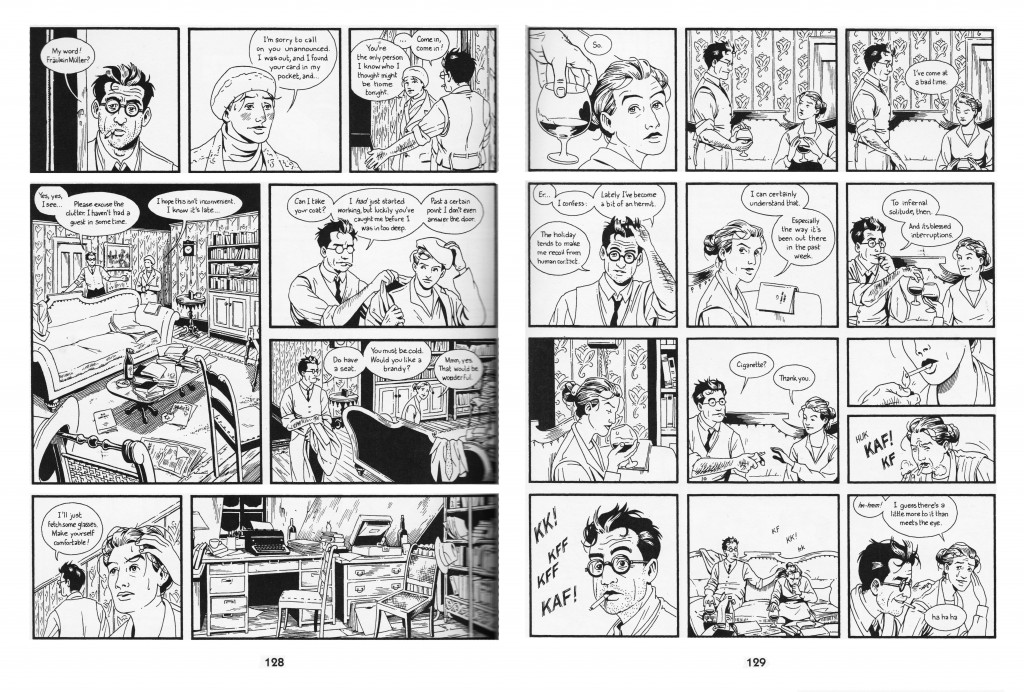

In one early episode, Juli suffers one of his recurrent fainting spells, a neurotic turn resulting from an earlier psychological trauma. It is perhaps the only time you will see an individual getting mouth to mouth resuscitation while he is having a “fit”. The fraudulence of this medical act suggest it’s placement—if it isn’t clear already—for erotic effect. The penis is verboten but a number of alternatives are grasped with both hands. A teacher’s attempt to stroke Erich with his cane is nothing less than a metaphor for the sexual tensions within the school. When the reigning queens of that exclusive institution arrange to converse with and touch Erich at a tawdry but chaste tea session, he barely manages to fend off their ministrations. This high tea of the mildly depraved is a kind of half-baked, elementary school version of the Hellfire Club where “Do what thou wilt” shall be the whole of the law.

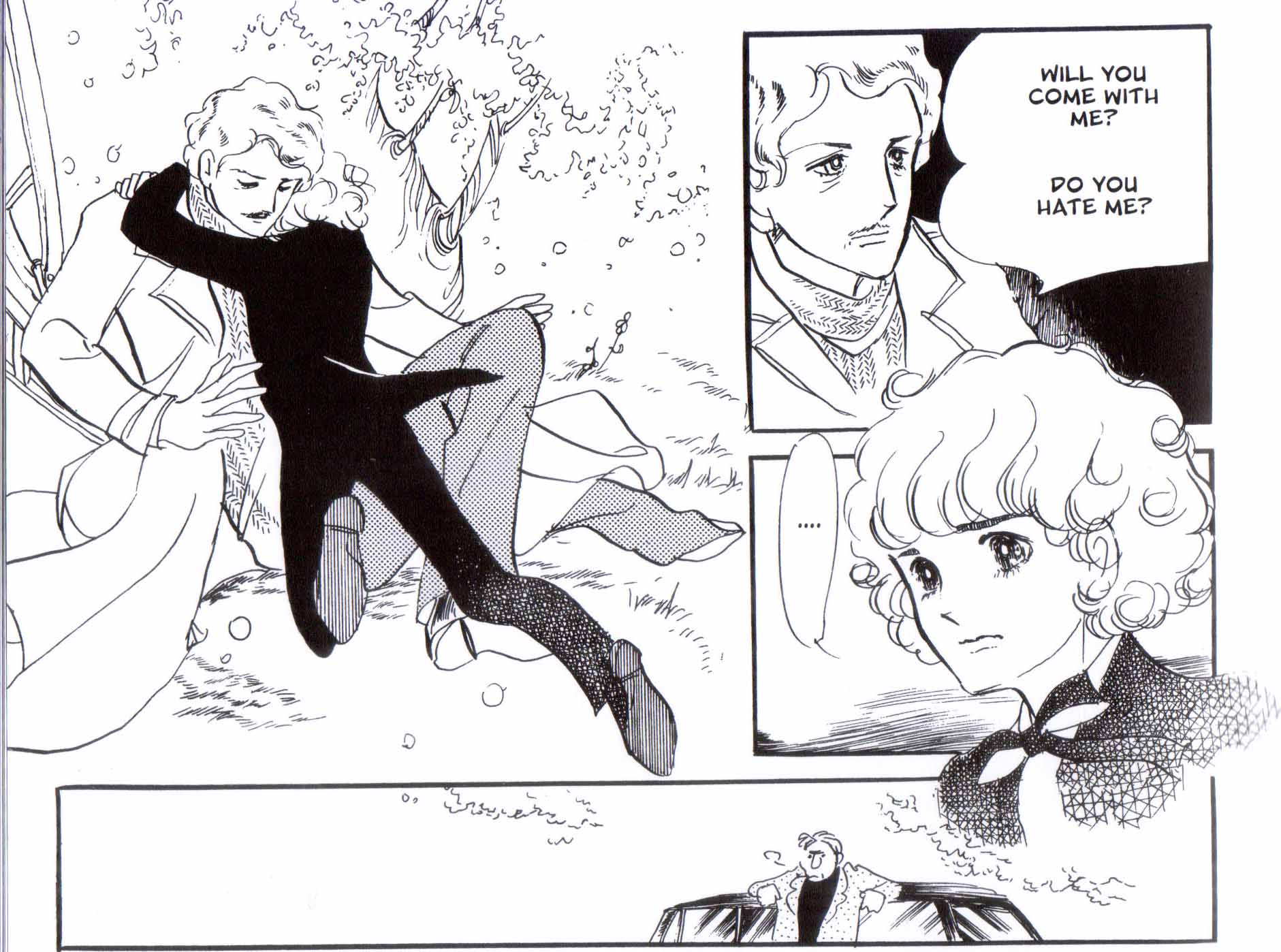

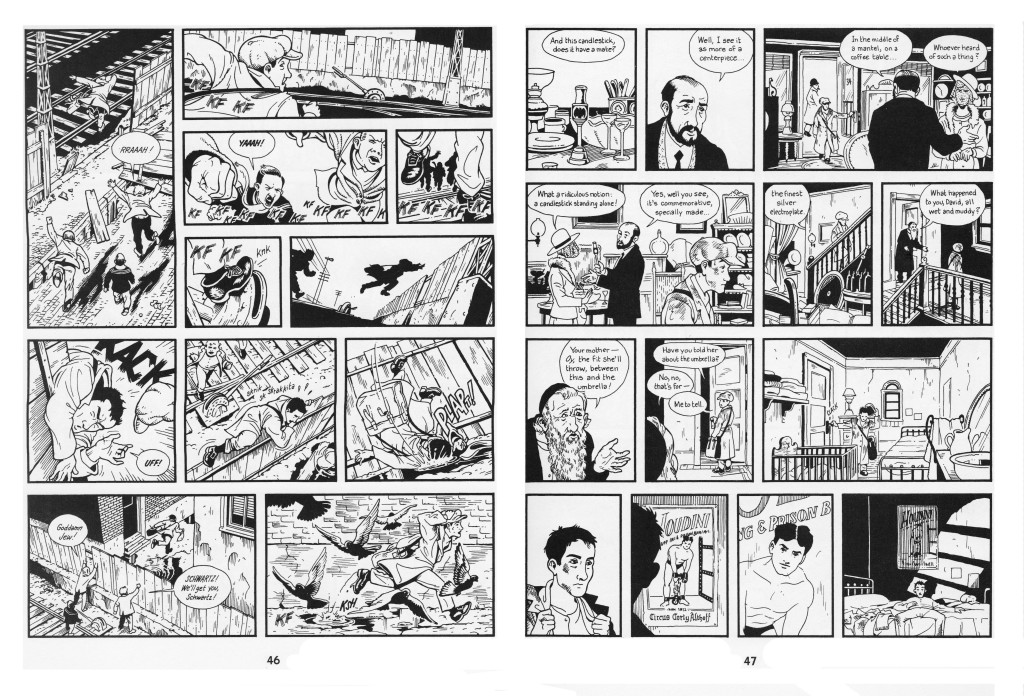

There is the pesudo-coitus—between Juli and Erich—of grasping with sharp objects: first in the fencing room and then, somewhat less subtly, in the bedroom with a pair of scissors. Later, Erich recounts a tale where he indulges in the predominantly male practice of autoerotic asphyxiation. These recurrent acts of strangulation are brought on by the sight of his mother kissing her lover—his mental torment (and patent mommy issues) relieved only by the death of his mother and a profession of fatherly love by his mother’s lover.

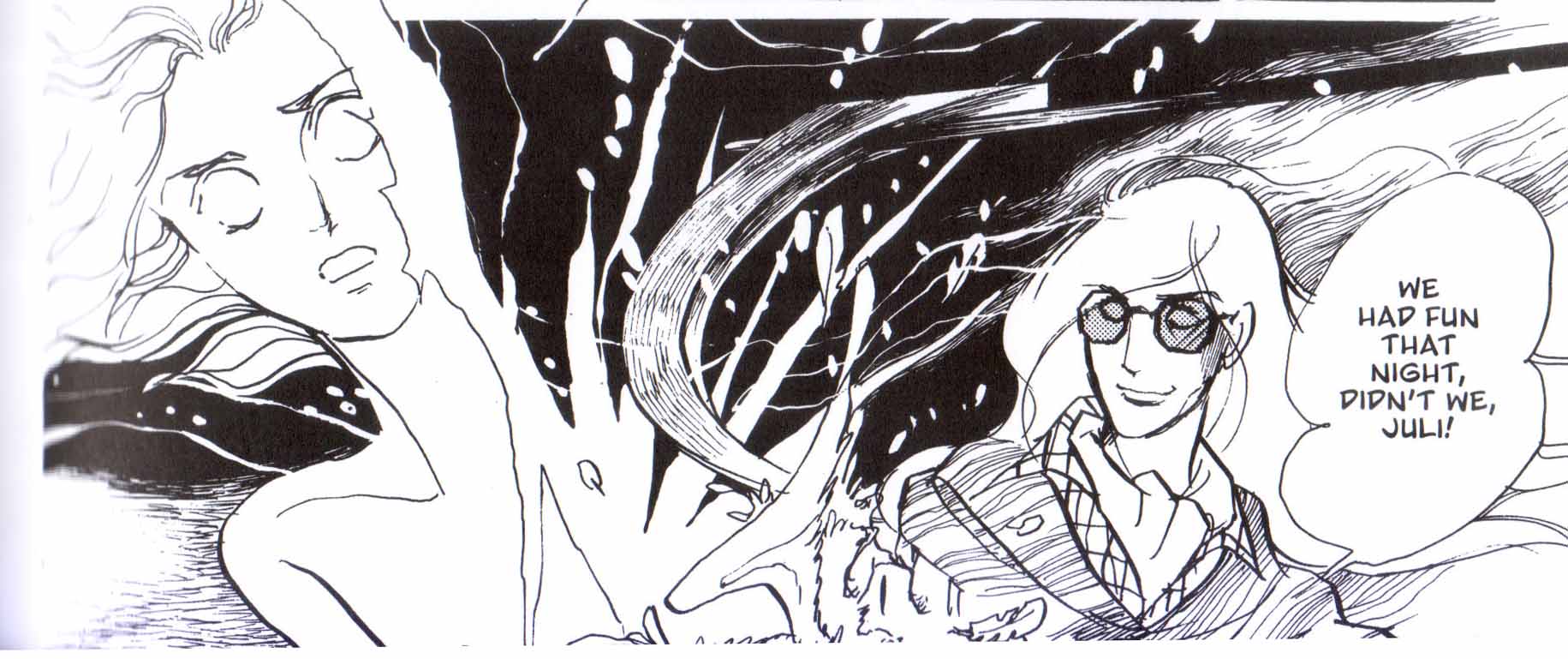

This incessant intermingling of pain, death, and love is Hagio’s idée fixe; and the purity of male love the panacea for all depicted ailments. The only exception to this gloss on idealized homosexuality (a fanciful and hopeful template for a paradigmatic relationship between the sexes) is Juli’s physical and likely sexual abuse at the hands of another student named, Siegfried—that swaggering, heroic betrayer of Wagner’s Ring cycle here seen as lascivious, preening monster with an appetite for sadism and young boys.

Erich’s allusion to a meeting between Beethoven and Goethe suggests the essence of the relationship at the center of Hagio’s manga. Here is an excerpt from a Gramophone article concerning Goethe’s feelings after that fateful meeting:

“Shortly afterwards Goethe penned a more qualified verdict to his musical guru Carl Zelter: ‘His [Beethoven’s] talent astounded me; nevertheless, he unfortunately has an utterly untamed personality, not completely wrong in thinking the world detestable, but hardly making it more pleasant for himself or others by his attitude.’”

Erich is of course Beethoven in our boarding school equation. Juli’s rejection of his “untamed” sensuality—forged and broken through terror by Siegfried—is the root of all his troubles. When Juli tells Erich, “I am going to kill you,” it is not merely a prediction based upon his earlier role in the death of Thomas Werner but a sign of Juli’s repressed sexuality—a disease which manifests itself in the weird science of mild attacks of “anemia” which have no basis in medicine.

The reader’s mileage with respect to Hagio’s subtle eroticism will vary depending on his/her passion for the artist’s figure work and for characters with brittle foreheads in need of warm towels. Not that these aspects aren’t apparent to Hagio. There is, for example, that moment of epiphany when one of the characters complains that his fellow students feel that he has “a girl’s face;” an otherwise unremarkable statement except for the fact that just about everyone in that boarding school looks like a pre-pubescent (i.e. breast-less) girl. To be sure, readers of The Heart of Thomas should always assume that every woman in Hagio’s work is actually a man until proven otherwise. This isn’t a problem so much as a feature of the genre, the attractiveness of slightly feminine men (or in this case feminized yet adequately virile men) being the entire point. To imagine the alternative—consider going to an action movie in which nobody dies and no violence is performed. It just wouldn’t do.

Noah in his article at The Atlantic offers little in the comics’ defense except for the standard, “Well, it’s meant to be crap and succeeds admirably at it.” Not his actual words of course, but here they are for those so inclined:

“In a lot of ways, The Heart of Thomas is an Orientalist harem fantasy in reverse. Instead of a Westerner thinking about veiled maidens on cushions in some distant palace, the Japanese Hagio fantasizes about beautiful boys in an exotic Europe.

The genre of boys’ love, in other words, allows Hagio and her readers to place themselves in a position of power and aggrandizement that is rare for women—as the distanced, masterful position, letting his (or her) eyes roam across variegated objects of desire….Thus, the prurient fan-service which is usually doled out only to men is here explicitly taken up by women, who get to watch more exotic male bodies than you can shake a spectacle at.”

And on Juli’s emotional (and likely physical) rape:

“Instead, Juli’s rape emphasizes the universality of what is often presented as a particularly female experience. Similarly, Juli’s shame, his self-loathing, and his tortured effort to allow himself to love and be loved, are all character traits or struggles which are often stereotyped as feminine. The fact that Juli is male seems, then, not an aspect of otherness, but rather a way to underline his similarity to Hagio and her audience. If readers can with Siegfried experience distance as mastery, with Juli they experience an empathic collapse of distance so powerful it erases gender altogether…The boys’ love genre, then, freed Hagio and her audience to cross and recross boundaries of identity, sexuality, and gender.”

As Noah periodically ejaculates on this blog, this is a case where the criticism is of far more interest than the text; a situation where purpose is more interesting than result, intention far better than the delivery, and (presumed) effect more fascinating than the actual reading experience. And if, as Noah claims, Hagio is an “aesthete”, this does little to explain the inadequate metaphors, and the banal structure and prose which litters the narrative. The romance here is as invigorating as ice on genitals. Certainly, nothing works so well to preserve mood than a comic chorus commenting on every loving decision and every act of forbearance. At every turn, the manga engenders not so much an “empathic collapse” but a complete nullification of empathy.

The tacked on and thoroughly mangled Christian metaphors (angels without wings; Judas and Christ; a cursory mention of justification) serve only to highlight Hagio’s poor grasp of European culture and religion in general. Even worse is the “shocking” revelation (of abuse) which is anything but. I let out a mental gasp of incredulity when the a plot twist near the close of the comic had Juli threatening to retire to a seminary; a time honored old chestnut seen in both modern and period Asian dramas since time immemorial where women have retired to nunneries for one reason or another. The immense superficiality and unadorned derivativeness of The Heart of Thomas suggests that whatever dividends one might gain from it are largely skin deep. It is nothing less than a time capsule of high camp.

Apart for the tangy taste of forbidden fruit, is the love of one man for another any different than the much more familiar sight of a man and a woman pining for each other? As both the novel and film adaptation of Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man suggests, the mere unfamiliarity of that object of affection is no hindrance to empathy. But just as truly great heterosexual romances remain in short supply in the medium (I’d be hard pressed to name more than a handful in manga and anime), so too does this rule apply to gay love in comics. Yet, to demand these standards of The Heart of Thomas is almost certainly a mistake for the comic in question was originally created for the enjoyment of women and has as much to do with the day to day issues of romance and gay love as the women in traditional harem manga have to do with flesh and blood females. Any resemblance to the gay liberation movement of the late twentieth century is simply good fortune if not purely coincidental. Some will say that the manga deserves praise because of its daring sexuality for its time—it is nothing less a seminal work in the boy’s love genre—but such a statement would be a demeaning admission that the comic is merely of historical interest.

The main inspiration for the manga at hand was apparently the film adaptation of Roger Peyrefitte’s Les amitiés particulières (novel published 1943, and film adaptation,1964). The similarities between the film and the manga are certainly striking.

There is the setting and sexual orientation of the protagonists as well as their relative ages. The lovers at the center of the film also struggle with ideas of purity and impurity (“It wasn’t his purity I loved.”) to the extent of expunging their sins of romantic (homosexual) love at confession. As with the final note left by Thomas, the letters between the young lovers act as erotic talismans. In the film, the letters are linked to the legend of St. Tarcisius—a young boy who defended the Blessed Sacrament with his life. These pieces of paper become nothing less than the body and blood of Christ to the lovers (they are certainly held in higher regard). Then there is the younger lover’s (Alexandre) suicide by jumping from a railway bridge (in this case, while traveling on a train) and the confusion of accident and suicide made more pressing in the film than in the comic because of the intransigent Catholicism which hangs heavy over the events.

While the love affair depicted in the film is not entirely convincing, it is certainly far more effective than anything found in Hagio’s comic. Peyrefitte’s work is restrained and classical in approach, and altogether more serious and real, especially in the interaction of the boys and a liberal minded priest named, Trennes. The priestly test commanded by Father Lauzon of the older lover (Georges; Juli’s counterpart) is nothing less than an act of temptation on the part of Satan. Hagio, of course, takes an alternative route. One might call it a disavowal of authenticity in setting, conversation, religion, and, perhaps, even sexuality—all of these becoming as putty and playthings in the authoress’ hand. A perfectly acceptable approach except for the decisive failure in delivery and communion.

The Heart of Thomas is in certain ways a sequel to the film, a fitful re-imagining of everything that could have been, but the final page of this book presents itself as a consummate evocation of my state of mind as I flipped through its pages.

The work was not clever enough, not brazen enough, not idiotic enough, and simply insufficiently well wrought to provide me with even a moment’s pleasure. It was, in short, interminable.