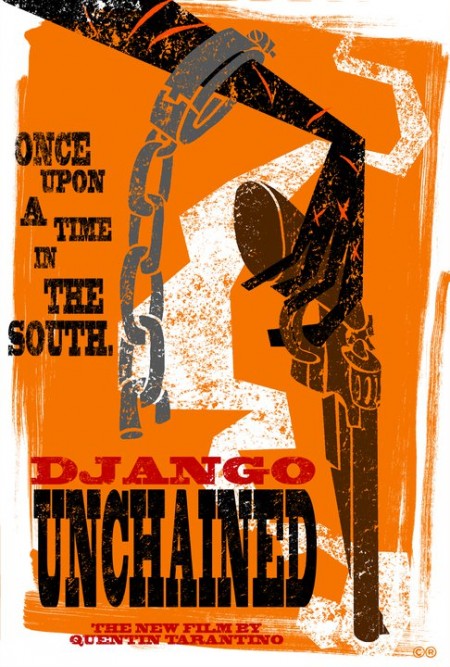

The entire Django Unchained roundtable is here.

__________________

Along with Inglourious Basterds, Django Unchained forms something of a diptych for Tarantino insofar as both are revenge fantasies set in two of history’s greatest atrocities: the Holocaust and American chattel slavery. In the interview he gave at the screening I saw last week, he certainly thinks of them that way. But before either film could begin to be written, one crucial difference in their respective historical situations delimited the possibilities of fantasy: one can fantasize about the end of the Holocaust by killing the highest members of the Nazi party, whereas there is no easily imagined personalized end to slavery through a few targeted acts of vengeance. Thus, the use of explosives against the Nazis seems a tactical act, a logical means of warfare. The use of bombs against slavery would border on what we call terrorism these days, or “irrationally” violent outbursts against a society (targeting civilians who can’t do anything to change the way things are, or think of the portrayal of the Watts riots, for example: why did they destroy property?). Slavery was a deeply structural violence, an ontological domination of a people that didn’t obtain in the instance of the Holocaust. Any heroic narrative set in the slave-built Southern economy is going to have a major hurdle to overcome: there is no real end in sight, the villain remains like the renewable heads of a hydra, nor is there a place to go where the hero’s limited victory will be recognized, much less celebrated (excepting the audience who might applaud at the film’s end). As Frantz Fanon famously wrote in Black Skin, White Masks:

The Jewishness of the Jew, however, can go unnoticed. He is not integrally what he is. We can but hope and wait. His acts and behavior are the determining factor. He is a white man, and apart from some debatable features, he can pass undetected. […] Of course the Jews have been tormented — what am I saying? They have been hunted, exterminated, and cremated, but these are just minor episodes in the family history. The Jew is not liked as soon as he has been detected. But with me things take on a new face. I’m not given a second chance. I am overdetermined from the outside. I am a slave not to the “idea” others have of me, but to my appearance.

I arrive slowly in the world; sudden emergences are no longer my habit. I crawl along. The white gaze, the only valid one, is already dissecting me. I am fixed. Once their microtones are sharpened, the Whites objectively cut sections of my reality. I have been betrayed. I sense, I see in this white gaze that it’s the arrival not of a new man, but of a new type of man, a new species. A Negro, in fact! [p. 95]

That provides an alternative to the film’s plantation owner Calvin Candie’s theory as to why slaves don’t rise up and kill their masters. He posits phrenology, that the black skull is built to encase a servile brain. (Odd how the guy doesn’t know words like ‘panache’ while being up to date on phrenology, but I digress ….) Instead of racist science: the slaves had little chance of escape — only a minority could get to border countries and the free states would return them without proof of freedman status (even freedmen had trouble fighting against a legal challenge to their status). More fundamentally and universally, there was little possibility for or hope of fundamentally destroying the system of white power that, as Fanon described, defined them on every level of “civil” society (including free states and the minds of many, if not most, abolitionists). Blackness was placed on the outside, no place, as mere alterity to whiteness. It was not purely coincidence that liberalism, the philosophy of liberty, developed alongside chattel slavery. Slavery gave dialectical meaning to liberty by providing the liberals with something to negate (e.g., the American colonies would not be the slaves to the English any longer). (I highly recommend Domenico Losurdo’s Liberalism: A Counter-History, which provides a mountain of evidence for liberalism’s primary theorists either outwardly supporting or giving backhanded defense to slavery on such grounds.) In Frank B. Wilderson’s terms, blacks experienced a structural suffering that is not analogous to the social oppression so many other groups have been under throughout history. For hundreds of years, they were denied ontological status, relegated to non-being. blackness constituted as a comparison to whiteness — i.e., what it meant not to be white or a subject and, by extension, what it meant not to be free.

Any imagined heroic solution cutting through the Gordian knot of cultural accretion that was slavery would’ve had to involve a consensus towards revolutionary-styled destruction, a restructuring of fundamental principles, namely a zero-sum ending to the civil war that begins 2 years after the film’s beginning. That Django’s final solution to Candie’s plantation wasn’t actually applied to the Confederacy itself resulted in another century of racial oppression that reverberated up through the 1960s reaction to the Democrat-driven Civil Rights Bill as the Southern states became Republican (the Democrats no longer being the anti-Black party). Thus, the moral contradiction at the heart of Django Unchained‘s narrative: by providing a fantasy of Django’s triumph and cathartic escape from the slave system, it supports the lie of Candie’s scientistic racial theory. That is, besides servility and cowardice, why didn’t the other slaves rise up the way Django does? Instead, I suggest a super-slave could no more put an end to slavery by destroying a personal target than Superman can punch out poverty. Success would be determined by the upswell of violence inspired by the hero’s symbolic actions against the corrupt system. Structural suffering isn’t something that can be solved or coherently fantasized about solving within the heroic-revenge generic story arc without turning the hero into a terrorist, which tends not to be most people’s ideal (unless a fan of Georges Sorel, like maybe Frank Miller). Unfortunately, Tarantino tries.

But first, what the film does right: I’m not sure any image in Django Unchained is any more perfectly ridiculous and depraved concerning reified blackness than James Mason’s rheumatic plantation owner placing his feet on a slave boy’s stomach in Mandingo with the superstitious belief that the pain will be absorbed from white to black. Nevertheless, there’s plenty of chains, whipping, dog mauling, infantilization, banal use of epithets and cannibalistic black-on-black violence to convey the slave economy’s dehumanizing processes. Together, these images provide the movie’s answer to an ensemble of questions that Wilderson refers to as descriptive: “what does it mean to suffer?” [p. 126] The ensemble addresses the ontology of black as slave, the structural condition of black suffering as fungibility and accumulation. True, like a superhero, Django is never in much danger of experiencing realistic trauma, but neither was Clint Eastwood’s Man with No Name. This is a fantasy, after all, and a comedic one to boot, so the audience doesn’t expect an onscreen castration of the titular hero no matter how close the knife gets. It also isn’t that important if Mandingo fighting actually occurred. As a phantasmagoric image of the black body as cannibalized remainder, black subjectivity having been commodified as pure exchange value, it remains effective. A bored son of privilege not requiring the economic appreciation of a good black buck, Candie uses the Mandingo slaves as a leisurely expression of his absolute sovereignty. Like a rich kid wrecking his BMW, he can always get another:

The relation between pleasure and the possession of slave property, in both the figurative and literal sense, can be explained in part by the fungibility of the slave — that is, the joy made possible by virtue of the replaceabilty and interchangeability endemic to the commodity — and by the extensive capacities of property — that is, the augmentation of the master subject through his embodiment in external objects and persons. Put differently, the fungibility of the commodity makes the captive body an abstract and empty vessel vulnerable to the projection of others’ feelings, ideas, desires, and values; and, as property, the dispossessed body of the enslaved is the surrogate for the master’s body since it guarantees his disembodied universality and acts as the sign of his power and dominion. [p. 21, Saidiya Hartman]

So despite its being a comedic fantasy, Django Unchained‘s horrific imagery conveys both bodily and ontological suffering under slavery. In fact, it takes a similar approach to blaxploitational horror (e.g., Ganja & Hess, Blacula), identifying the spectactor with what is typically the Monster/Other in Hollywood films to estrange normative positions: here, it’s Django, a black man as Slave, and Dr. King Schultz, a German traveler as Foreigner/Alien. (Mandingo, for example, is a tragedy about the plantation owning family and the Germans were almost completely alien in Inglourious Basterds, namely the enemy.) Tarantino is careful to acknowledge their differing ontological positions: Schultz doesn’t approve of slavery, but he’s still willing to use Django’s slave status to get what he wants, regardless of the latter’s desire. To paraphrase Fanon, whiteness can change with ideas, blackness is overdetermined by appearance.

It isn’t until later, after having been given his freedom, that Django reveals his goal to his erstwhile master, that is, to free his wife, Broomhilda (who we’ll soon learn is the property of the aforementioned Candie). At this point in the story, the two heroes’ relationship is, in the final analysis, characterized by an economic quid-pro-quo arrangement, not the developing friendship, which still needs the recognition of Django’s subjectivity. So Schultz will help rescue Broomhilda if Django will help out with the bounty hunting during a busy season just as he was freed for helping to locate the Brittle Brothers. The friendship becomes primary when Schultz gives up the majority of bounty he’s earned over the past year to pay for Broomhilda’s freedom. Although done under duress — Candie’s threat of bashing in her head with a hammer — the doctor clearly doesn’t think twice about the exchange: only the money is truly replaceable. With Schultz, a nonracist foreigner, we can see how the temptation of white power was entangled with the supposedly amorality of capitalist exchange. He resists the former by accepting failure at the latter.

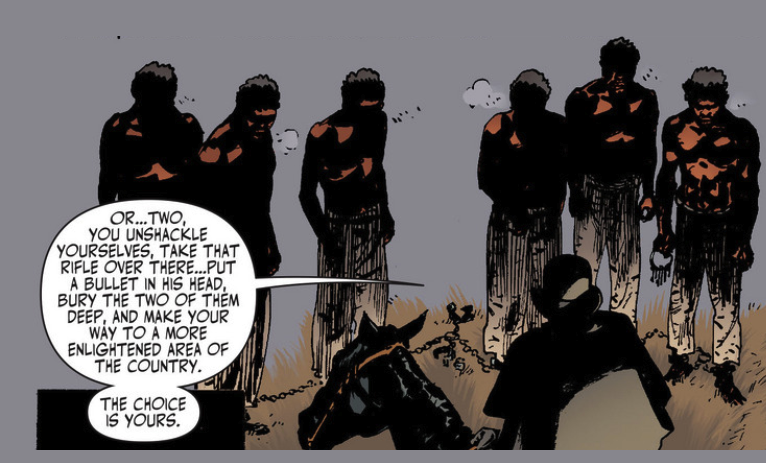

The moral setup is actually more complicated than Schultz’s development, though (which would’ve made the movie little more than another black tale about white awakening). On the way to the Candieland plantation, posing as a wealthy dilettante wanting to invest in Mandingo fighting with Django as his black slaver cum counselor, Schultz witnesses the way Candie deals with slaves who have lost their value. A fighter named D’Artagnan (after The Three Musketeers‘ protagonist) tried to escape because he felt too worn down to fight any more. Schultz loses his nerve, breaks character to save the slave from the dogs by offering to reimburse Candie. To repair the damage to their pretense, Django doesn’t flinch, saying this “pickaninny” ain’t worth buying, that Candie could do whatever he wants with his “property.” As Django explains, Schulz just ain’t as used to Americans. The foreigner looks as if he’s trying not to vomit, while the former slave returns a steely-eyed stare back at Candie as the hounds tear the decrepit fighter apart. This scene is pivotal as it shows just how desensitized to the spectacle of slavery Django is (his ability through habituation to suppress a horror too great for the white outsider) and how far he’s willing to go to get his wife back: D’Artagnan’s life for hers. Similarly, throughout the trip, as part of his act, he’s shown to be harsher on the slaves in chains than any of the real slavers in order to keep Candie “intrigued.” For the time being, he’s committed himself to the system of slavery, going beyond what it demands of him, in order to save the one person he truly loves. In his willingness to go through hell, Schultz compares him to the German myth of Siegfried. In other words, he must treat all slaves as fungible to rescue Broomhilda. Only she is seen as an irreplaceable subject.

In the next scene, arriving at Candieland, we’re introduced to Django’s mirrored antagonist, the “Uncle Tom” character of Stephen, which is where the film’s main problems lie. As Django had previously explained, the house negro is the lowest of the low, with the only thing lower being the black slaver. However, there’s one role he omitted: the white slaver as the representative of slavery itself. The reason Django remains sympathetic even after sentencing another black man to a brutal death is because of the enculturation to abject horror that’s forced on any survivor of such totalizing oppression. It wasn’t as if slaves could appeal to OSHA about the unjust treatment of one of their fellow slaves. Whistleblowing during slavery had no meaning, since the law enforced injustice. The “whistleblower” risked his own life for no possibility of justice. Thus, one had to learn to live with the violence. This habituation to depravity is what allows Django to stay focused on his goal. He can’t rescue every slave he comes across any more than all the slaves could’ve just fled to Canada to live a just life, equal to whites, because the manifold problems of slavery are structural, not just personal. If he had let Schultz save D’Artagnan, then it would’ve been more likely that Broomhilda’s life was being traded for a slave he had never met. This is not some utilitarian “greatest good” rationale being arrived at by the slave, but a forced choice being made for him by the white power structure in which he can do little more than survive. A lesson from Hitchcock’s Lifeboat: if one can’t save everyone in a lifeboat, then be willing to push some off the side and get used to the sounds of drowning. That, and it’s better to not save a spot for complete strangers.

Why, then, if the audience can still sympathize with a flawed hero who has to do some bad things because of an immoral system that doesn’t permit him a rational, disinterested reflection on the universal good, are we presented with Stephen, a potentially complex character, in such a simplistic, caricatured villain role? He’s revealed not as another slave who’s doing what he can to survive, any possibility of self-assertion narrowly circumscribed under the gaze of white power, but rather the maniacal evil genius behind the entire Candie clan. Consider: (1) He’s the first person shown to torture Broomhilda and it’s Candie who stops it. (2) Candie doesn’t figure out the con Django and Schultz are pulling, but Stephen does. He reveals it while sipping brandy in the library, holding the snifter like a Bond villain, and calling his “master” by his first name, Calvin. (3) After Candie’s death, it’s Stephen who gets all his master’s henchmen to stop firing while he negotiates Django’s surrender. Billy Crash has a gun pointed at Broomhilda’s head, but he doesn’t fire after Django throws down his gun because Stephen said she would live. Why would Crash care what one slave promised another? (4) Furthermore, he doesn’t castrate Django, because Stephen has convinced Lara Lee (Calvin’s sister) and the rest of the gang that breaking rocks at the mines is a much worse fate. (5) And, finally, if Stephen’s total control isn’t obvious enough, after everyone else has been killed, this antebellum Wormtongue throws down his cane and stands up straight to reveal his lameness an act. Whereas Django had to play tougher than he was, Stephen played weaker. They’re inverted images of each other: the former lied to protect someone from power, the latter to gain power (or, more sympathetically, to protect himself from power).

The reason for the appearance of a mustache-twirling cliched role (despite some admittedly funny, witty lines and a great performance by Sam Jackson) is, as I suggested above, the heroic-revenge generic structure. It requires a personalized villain of sorts, not a structural evil with which even “good” citizens are complicit. And what’s more personalized than the evil doppelgänger? For once, genre constraints have gotten the better of Tarantino. Thus, the film is an abysmal failure at addressing the other ensemble of questions Wilderson delineates, the prescriptive: “How does one become free of suffering? [Those] questions concerning the turning of the gratuitous violence that structures and positions the Black against not just the police but civil society writ large.” [p. 126] By giving the story a revenge motive, Tarantino reduced the suffering to a personal level, a subjective violence that one person might do to another — kill the oppressor, stop the oppression. This is a “failure,” because it applies a subjective resolution to a structural problem that was fundamentally the negation of subjectivity; “abysmal” because it achieved the biggest cathartic thrill with the killing of a black slave instead of any number of plantation owners in the film. If Tarantino had to make it all about subjective revenge, then why ignore the most narratively plausible candidate, Old Man Carrucan, the malicious old bastard who had treated Broomhilda and Django so cruelly and then sold them to separate owners out of spite after they attempted to run away? But it’s not even Candie who has the last, big face off against Django; it’s Stephen. Django mows down every trace of whiteness in the final (majestically rendered) gunfight, saving the fate of “snowball” for the big finale. Evidently, the house negro is more evil than the master.

Tarantino has expressed in the past (on Charlie Rose) a keen interest in what I’d call the terrorist as symbolic hero, namely in his desire to do a biopic on the radical abolitionist John Brown, one of the director’s favorite historical Americans. With a self-described holy purpose, Brown sliced open the heads of pro-slavery activists along the Pottawatomie Creek, who hadn’t actually killed anyone themselves, was willing to go on a suicide mission at Harper’s Ferry in an attempt to inspire a mass uprising against slavery and, once caught, refused any possible chance to avoid hanging for a chance at martyrdom. As James McPherson tells it, “Democrats and conservatives denounced Brown as a lunatic and murderer” and the Republicans did their best to dissociate their abolitionism from Brown’s techniques. [p. 35] In other words, he was no more popularly recognized as a hero in the nineteenth century than terrorists are today. At least, among whites; blacks have mostly called him a hero (except pacifists like Martin Luther King, Jr.). Why not use this white abolitionist’s revolutionary violence as a model for Django’s own? It’s not like sympathetic terrorism as entertainment isn’t fairly popular these days: Che, Carlos, United Red Army, and, in a way, Homeland. Instead, each vengeful kill that Django makes is shown to be related to a personal act of violence against him or his. There is no killing of pro-slavery people who aren’t themselves shown to commit subjective violence. Each person acts as an individual and another reacts, ignoring the dangerous question of structural responsibility expressed by Malcolm X: “if you [whites] are for me — when I say me I mean us, our people — then you have to be willing to do as old John Brown did.” [p. 38]

Hartman’s Scenes of Subjection provides a plausible analysis of what’s going on here. She argues that in abolitionist literature, melodramas and eyewitness accounts from whites, there was an empathic tendency that attempted to make the horrors of slavery palpable to whites by projecting whiteness into the place of the black body in pain. This effectively erased the black person doing the suffering, making it a performance for white affect, and not unrelated to the way slaves had to perform for masters as if they accepted, even enjoyed, their subjugation. As she writes in the quote above, “the captive body [was] an abstract and empty vessel vulnerable to the projection of others’ feelings, ideas, desires, and values.” Thus, black suffering was narrated through the master’s discourse even for abolitionists. Let’s face it, other than avowed racists, what contemporary white people would fancy themselves as pro-slavery in a historical melodrama? Dreams of terrorism are probably more likely, despite the damn good chance that slavery sympathizer is what we would’ve been in such times. So, instead of a critical reflection of Django’s narrative, complicating his own generically derived existence as black performativity (cf. blaxploitation), Stephen is treated as little more than a blackface projection for white fantasy. As Tarantino has stated over and over in interviews, he clearly wants his audience to take sides, cheer at the ending — not, I conclude, reflect on the problematic that the house negro presents. Django is the oppressed that white folk would like to be in such a situation, fighting for freedom (just as they would now, of course), with Stephen’s freely working for subjugation the negation that gives such freedom meaning — as if chattel slavery and its concomitant subjugation of black identity were a choice made by the subjugated! This is, once again, Candie’s theory, only without the biological determinism. And when the film has audiences cheering Stephen’s downfall, one should recall the earlier scene of Mandingo fighting, in which one man’s death is reduced to spectacle for Candie and his guests.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Fanon, Frantz (1952/2008), “The Lived Experience of the Black Man,” Chapter 5 in

Black Skin, White Masks. Translated by Richard Philcox. [An older translation can be read

here.]

Hartman, Saidiya V. (1997), “Innocent Amusements: The Stage of Sufferance,” Chapter 1 in Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America.

McPherson, James M. (2007), “Escape and Revolt in Black and White,” Chapter 2 in This Mighty Scourge: Perspectives on the Civil War.

Wilderson III, Frank B. (2010), “The Ruse of Analogy” and “Cinematic Unrest: Bush Mama and the Black Liberation Army,” Chapters 1 and 4 in Red, White & Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms.