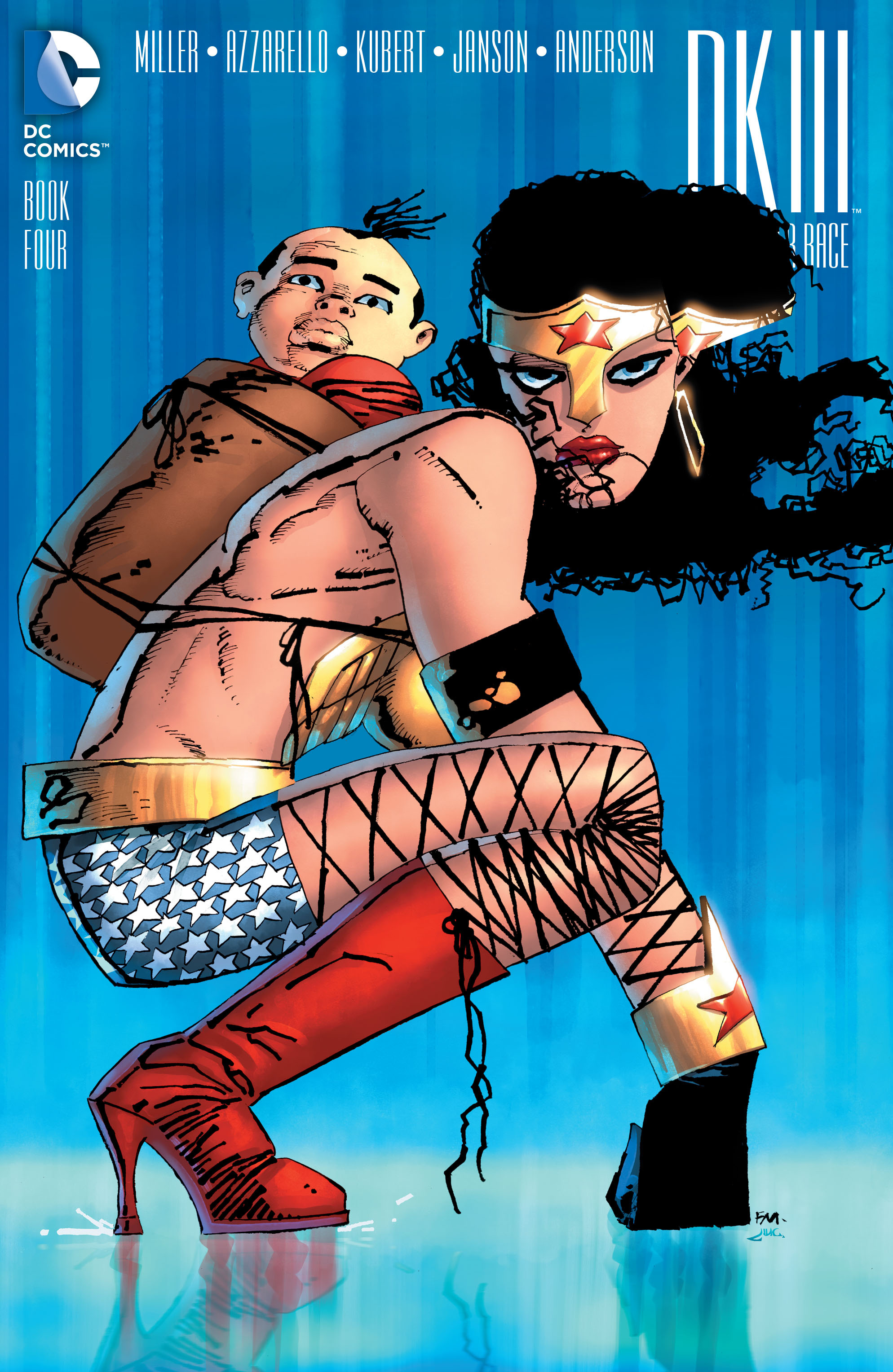

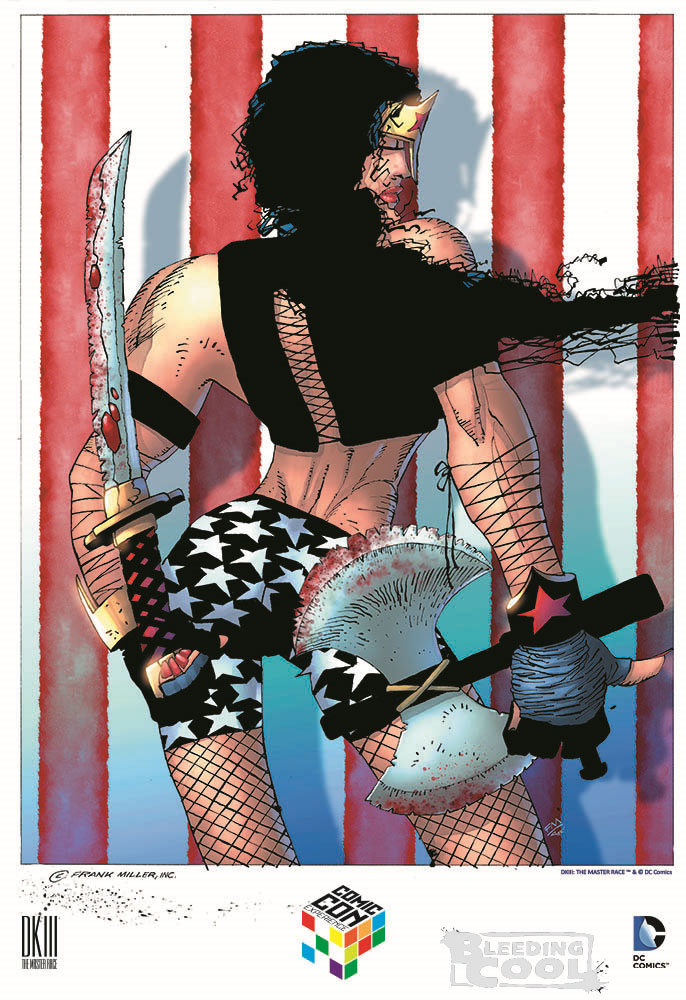

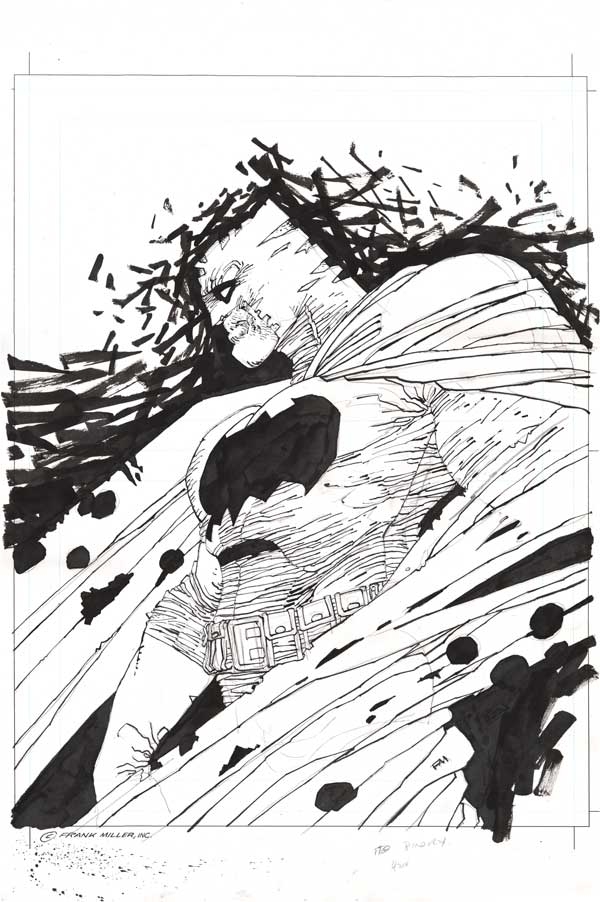

Earlier this week Suat wrote a post on Frank Miller’s recent artwork, which shows signs of steep technical decline. Miller’s draftsmanship was never stellar, but he had a strong, dramatic sense of design, and a consistent, idiosyncratic stylization that mixed Kirby, Frazetta, and manga in a way that wasn’t off-puttingly derivative of any of them.

As Suat says, Miller’s recent work shows a steep decent from this good-if-never-great peak.

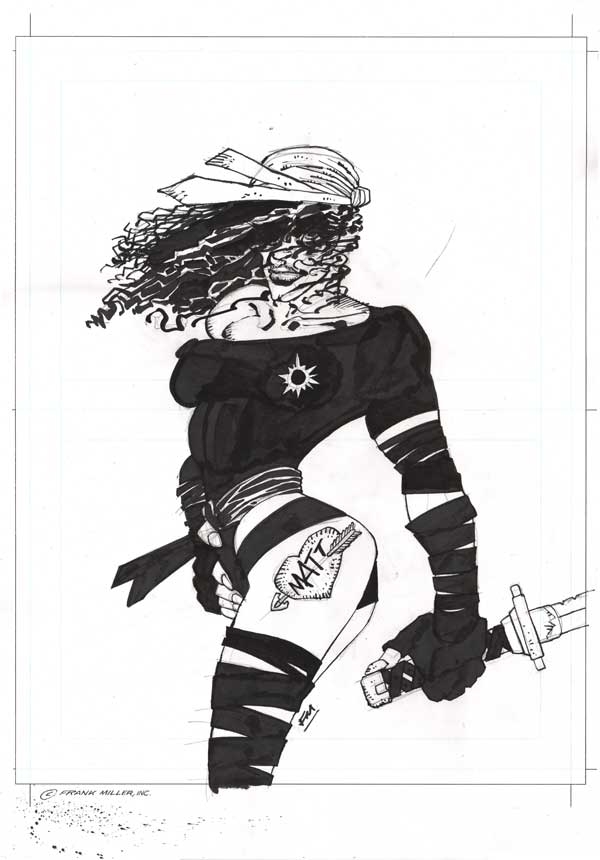

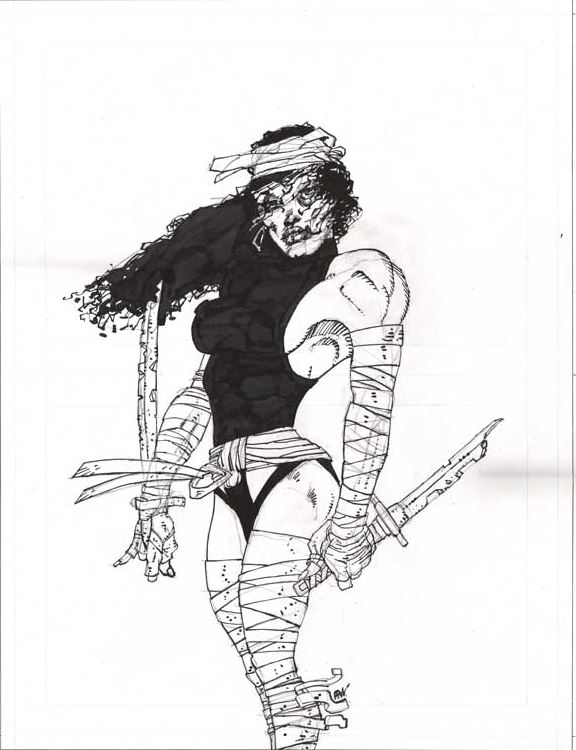

Interestingly, Dan Nadel expressed some appreciation for this late Miller of the ugly Frankenstein zombie Elektra with arms taken from some other, bigger zombie woman.

I understand why people would dislike this new stuff. It’s ugly and incoherent, but coherent Miller isn’t that interesting to me, and I like ugly sometimes. Free of his obvious influences — Eisner, Adams, Moebius, Kojima — he just made weird work. Intentional? Maybe not. Maybe so. We’ll probably never know. It’s not genius or anything… just odd end-of-career work by a pulp artist, kinda like Lee Brown Coye’s late work. Consistent in its weirdness. Certainly the covers he’s drawn in the last year are all of a piece, and make sense as slightly deranged mark-making.

That’s an outsider art take; Miller gets more interesting as he gets less controlled and less coherent. As the control over the material disintegrates, you can appreciate the images not as representations of superpeople, but simply as lines on the page; “deranged mark-making”, which happens to look like zombie Elektra, but really could just as easily be something else for all Miller, or the viewer, cares.

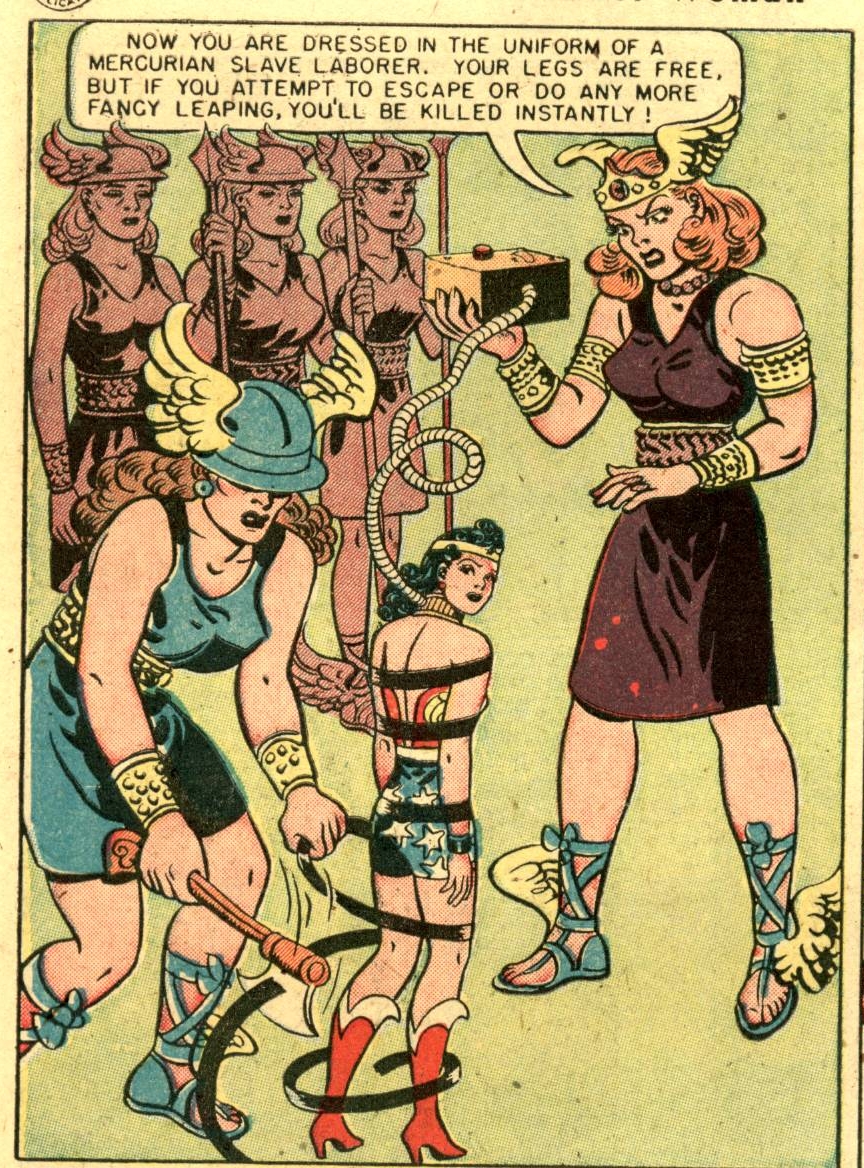

I don’t know that I entirely buy Nadel’s take; Elektra is too obviously a struggling picture of Elektra to appreciate it as simply disincorporated pencil tracings,and the ugly isn’t quite weird enough to send me. This isn’t Harry Peter, where confused proportions and oddly defined composition create a vertiginous sense of spacelessness, with the figures hovering between characters and two-dimensional pen marks.

There’s incompetence and then there’s incompetence. Peter’s scattershot drafting and compositional skills resolve into an alienating, sublime effect. Miller’s ugliness just sits there, sadly, asking you to admire it as beauty.

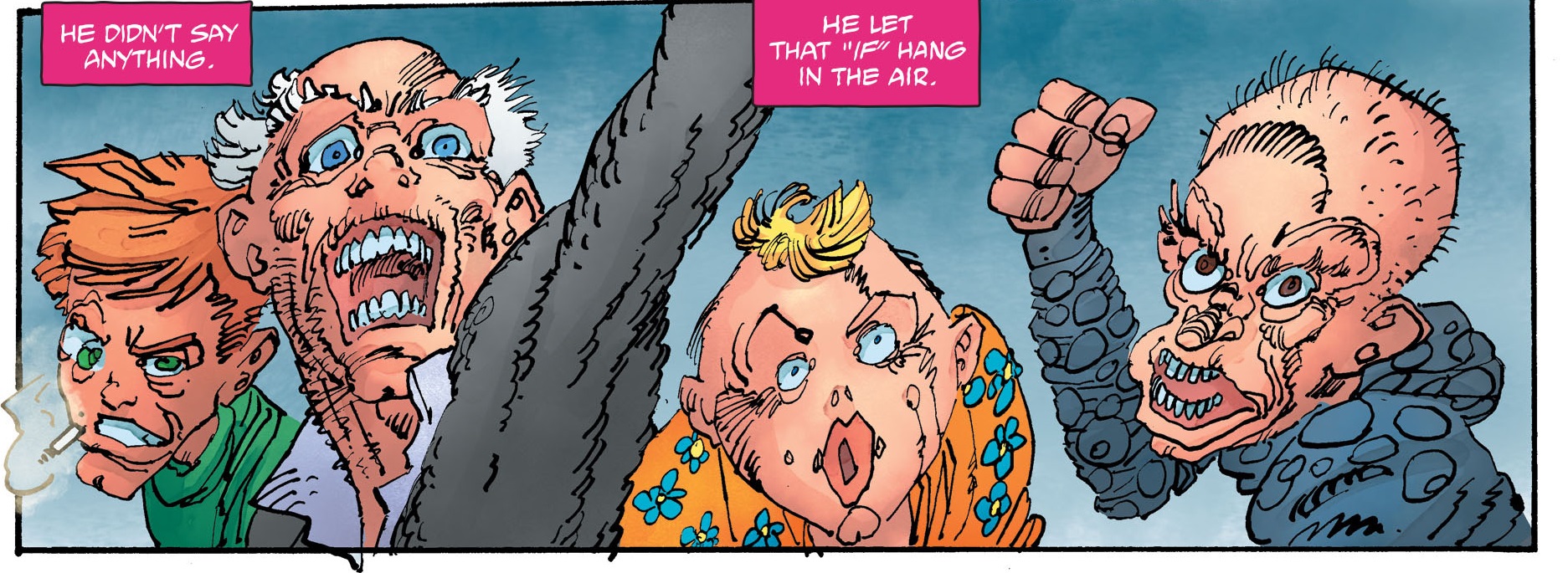

Still, I don’t actually hate that Elektra drawing the way I hate, say, the art in Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers, or for that matter the art in a lot of mainstream superhero books.

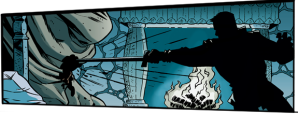

I guess that’s by Mike McKone. I guess this is the sort of thing that comics fans think is acceptable, as opposed to Miller, but…that’s pretty sorry shit, isn’t it? There’s something seriously wrong with the foreground character’s anatomy; her stomach seems to trying to escape through her backbone. The composition is static and awful; they’re all just standing there looking serious, thinking deep thoughts like, “wow, we’re really poorly drawn, aren’t we?” The coloring is slick and bland, they’re all thin and bland and straight; it’s a bunch of superbored supersticks. If you could pan down, you’d expect to see that they all have wooden feet hammered into the ground.

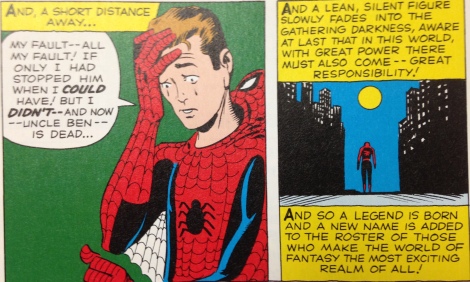

Miller’s Elektra isn’t cool as shit action art a la Frazetta, and it’s not outsider art interesting—but at least it’s trying something. Elektra is supposed to be sexy and badass, and she fails at that…but at least the failure registers as a failure. He tried something and it didn’t work, and it’s kind of funny and kind of sad. It doesn’t get to ugly enough to be good or interesting, but it’s got enough ambition to get to ugly. Mike McKone’s drawing, on the other hand, is so bland it makes no impression; like much superhero art, it might as well just be a scrawl declaring, “art needed here on deadline.”

Frank Miller is a big enough deal that when he turns in art, he actually turns in art. Not good art, necessarily, but not personalityless corporate default, either. You look at Elektra, and you feel like Miller put some of himself in there, even if that self is an indifferent draftsman far past his prime. I guess that’s what it is to be a mainstream superhero artist these days; you work and work in the hopes that you’ll become popular enough that someday, somehow, you’ll be allowed to make the crappy art you’re truly capable of.