Having already talked about framing and layout and closure and abstraction, I’m backing up now to what should be square one for “Analyzing Comics 101.” Who are the creators doing all of this framing, etc.? Although Will Eisner’s 1940s Sunday newspaper section The Spirit is a significant exception, superhero comics are typically created by multiple authors, with production divided into five semi-independent roles.

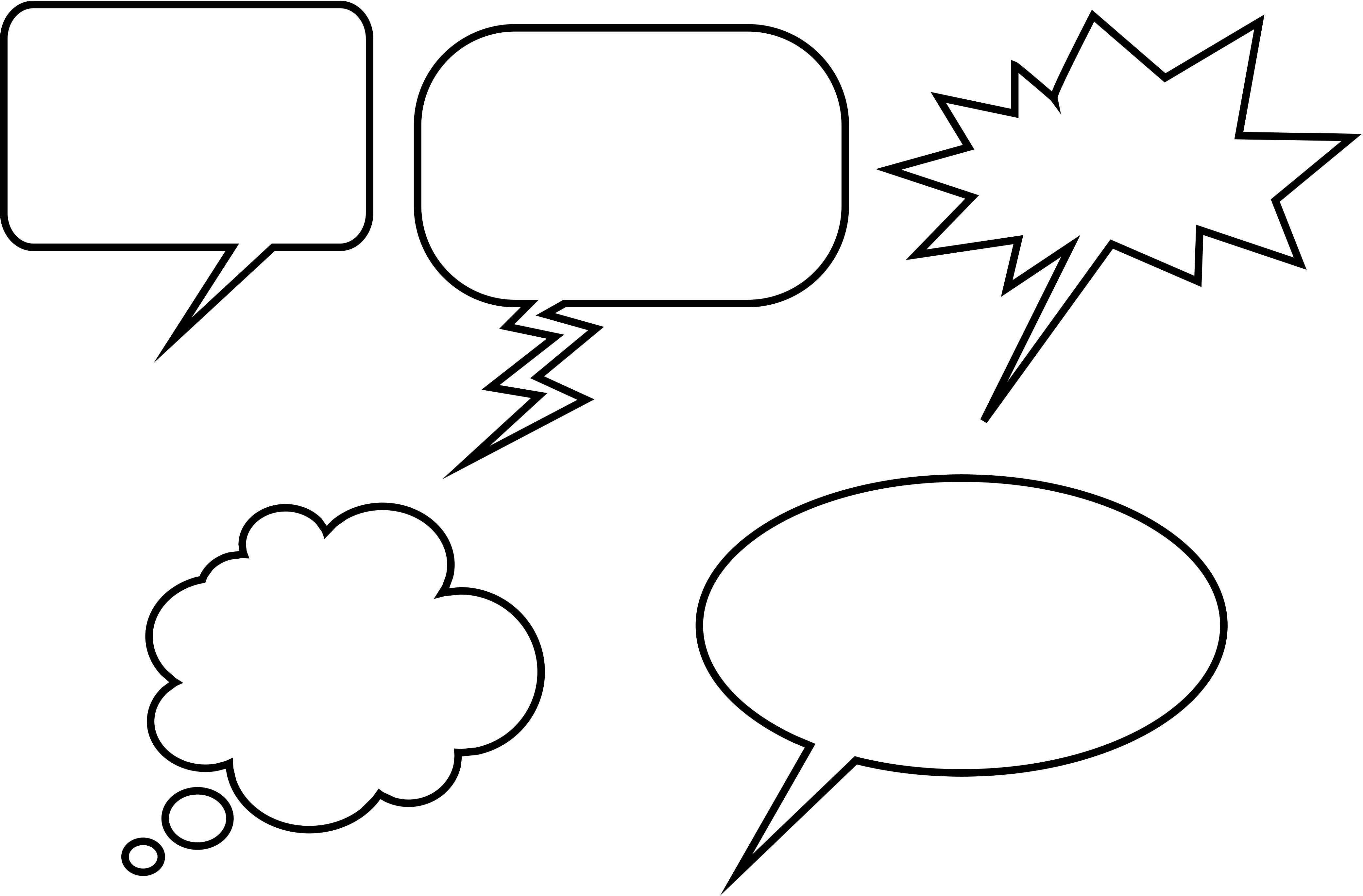

Writer: Creator who conceives the story idea, plots the events, plans the content and sequence of panels typically through a written script, and/or composes the words that appear in caption boxes and word balloons. The various writing roles may involve more than one individual.

Penciler: Artist who sketches the pages, typically based on a writer’s script. A superhero comic typically has only one penciler.

Inker: Artist who finishes the pages by penning over the penciler’s breakdowns. More than one inker may be involved in a single issue, and a penciler sometimes inks her own pencils.

Colorist: Artist who designs or co-designs color or gray tones and adds them to the inked pages.

Letterer: Artist who draws the scripted words (but not sound effects) inside balloons and boxes.

The words and images in a comic book are the product a complex and sometimes overlapping creative process. Although rarely credited, a penciler often co-writes by making encapsulation and layout decisions and sometimes creating content based on the credited writer’s story summary. 1950s Marvelman writer Mick Anglo wrote no scripts, but “would instead suggest a basic plot outline to an artist, giving him a specific number of pages to fit the idea into. Once the art was complete, Mick would then write in the actual wording for the letterer” (“Miracleman Alias Marvelman”). Stan Lee followed the same process in the 60s, dubbing it the Marvel Method. Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko would also sometimes conceive and pencil stories independently, leaving margin notes for Lee to expand into dialogue and narration. Job applicants seeking writing positions were hired based on their ability to fill in four pages of empty talk balloons and caption boxes from Fantastic Four Annual #2, further suggesting that pencilers were often the primary “writers” at Marvel.

Even when working from full scripts, pencilers may exert a great deal of creative control. According to 90s Deathlok writer Dwayne McDuffie, penciler Denys Cowan “felt free to alter my panel breakdowns and shot descriptions whenever he had a better idea” (28).

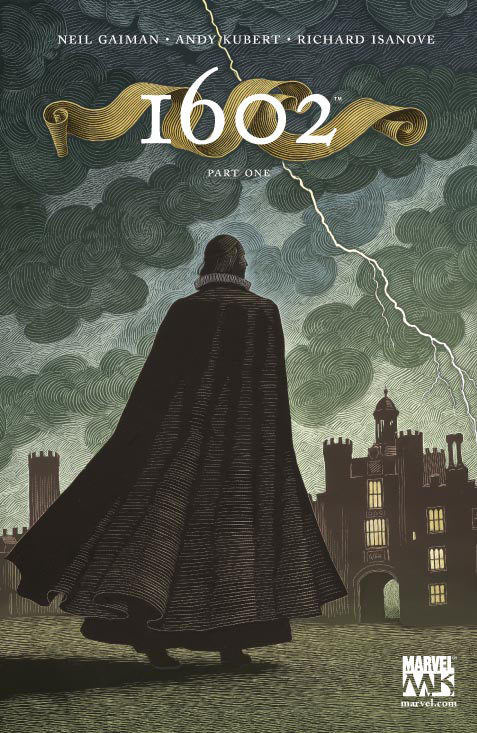

Neil Gaiman even encouraged Andy Kubert to alter his 2003 scripts: “Feel free to ignore my suggestions if you can see a better way of doing it. (You are the artist.) … Also, there’s an awful lot to cram in here, so let me know if you need more room, and if I’m trying to jam in too much…” (Marvel 1602).

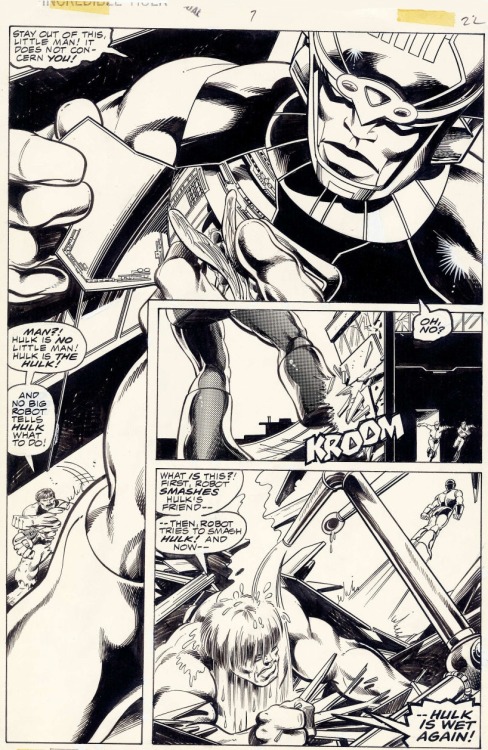

Penciler and inker relationships are complex too. Inker Eric Shanower was notorious for adding details to layouts, while Vince Colletta was notorious for eliminating them. John Byrne even voiced homophobic complaints about Bob Layton’s inking of his work:

I actually feel physically ill when I look at Bob’s stuff. […] It’s like everything is greasy and slimy. […] all his men are queer. They have these bouffant hairdos and heavy eye make-up and an upper lip with a little shadow in the corner which to me says lipstick. Even the Hulk. I will never forgive him for what he did to the Hulk’s face in the annual that we did together.

I remember my father looking at […] the finished inks […] and my father said, “Well this guy’s queer.” No, he didn’t look queer in the pencils, Dad.

When John Byrne inked Steve Ditko in the 80s, their styles clashed queerly too, creating Byrne-detailed figures arranged in signature Ditko poses.

Unless the penciler is instead painting in a color medium—Alex Ross prefers gouache watercolors—color is added to comic pages last. Before Photoshop, this was accomplished during the printing process by overlaying color-separation boards and screening ink by percentages in dot patterns. The colorist would select color combinations for each discrete shape, and multiple assistants would cut the shapes from each board. Color decisions might also be indicated by the writer in a script or by the penciler in the margins of the layout. Because the artists’ boards remained black and white, colors can be altered with each publication. Alan Moore and Garry Leach’s first chapters of Marvelman originally appeared in black and white in Warrior magazine in 1982; the retitled Miracleman #1 was reprinted in color in 1985 by Eclipse Comics; and Marvel Comics reprinted it again in 2014 with a new color design by Steve Oliff. (Kevin Melrose discusses this in more detail here.)

The final product of a comic book consists entirely of ink on paper (originally the lowest grade, pulp paper), but the images are the result of multiple processes. At times it is useful to discuss each contribution independently, while at other times such divisions may be burdensome or indeterminable. Nathaniel Goldberg and I in “Economy of the Comic Book Author’s Soul” analyze contributors as a single, pluralistic author whose words and images display unified intentionality. We might also analyze a given comic as though it has agency itself. Unlike a traditional painting—which may be copied and mass distributed—a comic book is its multiple copies. The artboards may be considered works of art too, but the artboards are not the comic book produced from them. A comic book has no single original.

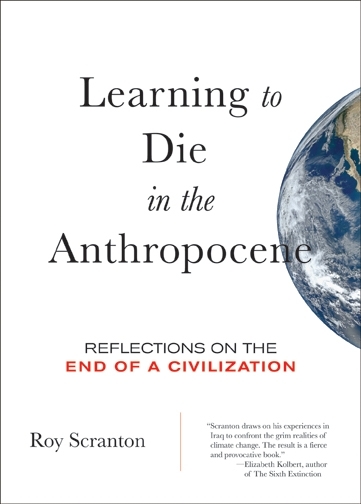

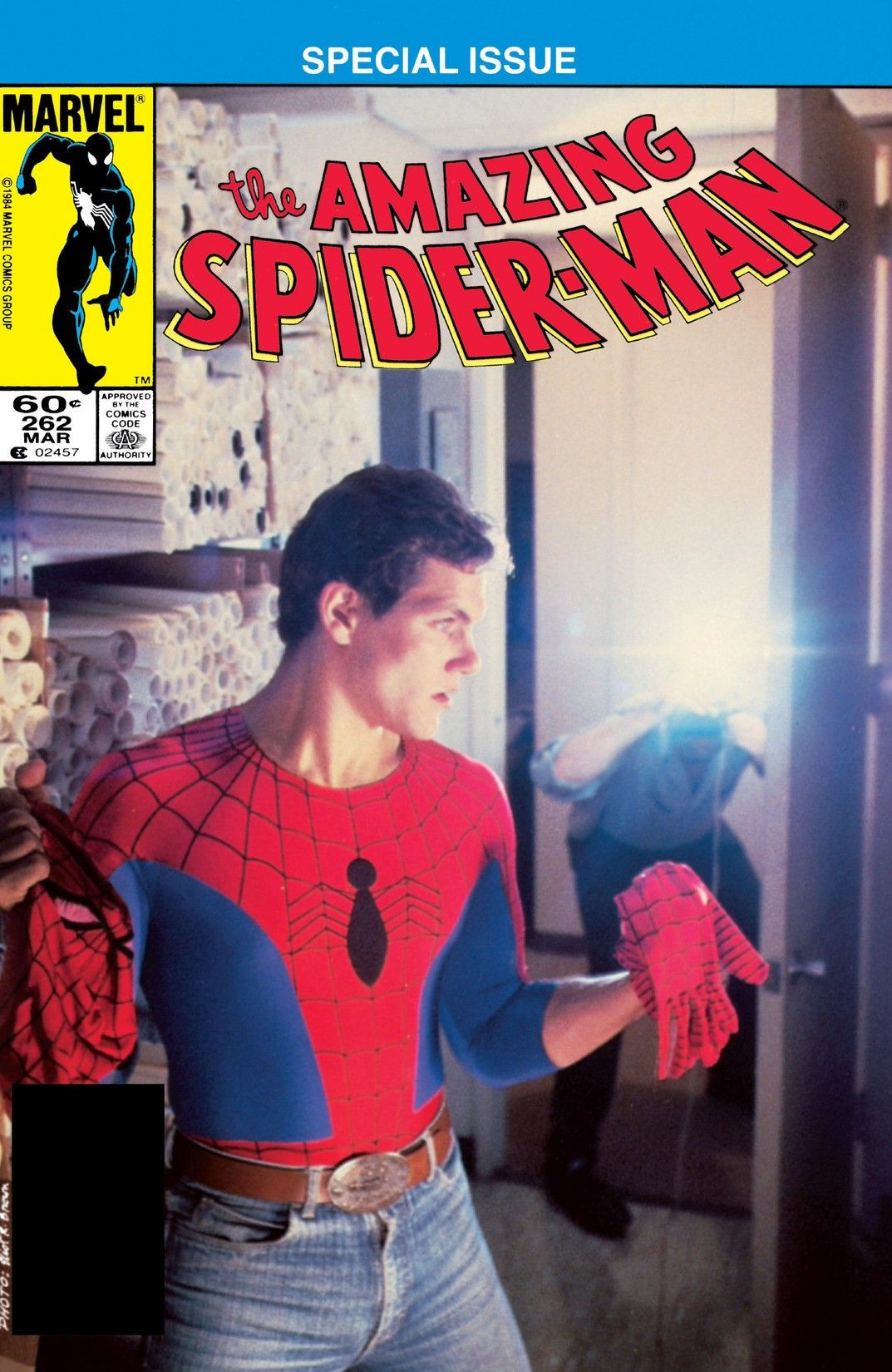

Superhero comics, because they tell stories through representational images, also create tensions between how a subject matter is depicted and the subject itself—in other words, between the story world of the characters (diegesis) and the physical comic book in the world of the reader (discourse). No tension between diegesis and discourse occurs in prose-only texts because the words on the page in no way resemble the world they linguistically evoke. But because comics discourse includes representational images, their diegetic content is ambiguous. Is a drawing of a superhero a photo-like document of the superhero as others in the story see him? Or is the drawing an interpretation of the character which may be in some way diegetically inaccurate?

This tension does not occur (or occurs much less) in the non-fiction of graphic memoirs and graphic journalism because the images represent real-world content and so are understood as interpretations. Graphic novels, because their content is fictional, create a greater tension, and superhero comics, because they are an amalgam genre that includes fantasy and science fiction, heighten it by depicting subject matter that both does not and often cannot exist. The diegesis-discourse tension poses a question: Do comic book superheroes exist as they are depicted, or do they exist independently from their depictions? This is a philosophical question I can’t resolve here, but the tension is a factor when analyzing superhero comics visually.