Having taught my spring term seminar Superheroes a half dozen times now, I’m converting it to one of the gateway courses for Washington and Lee students entering the English major. The overhaul means jettisoning the pre-history of the genre (I love that stuff, but I could just hand my students On the Origin of Superheroes and be done with it) and focusing much more on comics as an art medium. So I’m trying to boil down the basics, the must-know criteria for analyzing a comic book.

So now it’s time to invite Neil Cohn to the lectern. If you haven’t read his The Visual Language of Comics, please do. Meanwhile, here’s my boiling down of his visual language grammar.

Narrative panel types: images may be categorized according to the kinds of narrative information they contain and how that information creates a visual sentence when read in sequence:

Orienter: introduces context for a later interaction (no tension).

Establisher: introduces elements that later interact (no tension).

Initial: begins the interactive tension.

Prolongation: continues the interactive tension.

Peak: high point of interactive tension.

Release: aftermath of interactive tension.

Cohn only looks at comic strips, which typically express a single sentence in a linear arrangement of three or four panels, but longer graphic narratives can express multiple sentences on a single page or extend a single visual sentence over multiple pages. To analyze the different ways that can work, I’m adding some terminology to Cohn’s.

Closed sentences: two sentences that begin and end without sharing panels.

Overlapping sentences: sentences that share panels.

Interrupted sentence: an overlapping sentence that does not complete or initiate its tension before another sentence replaces it; sentences might share an Orienter, or an Establisher may introduce two elements that do not interact until later as a form foreshadowing.

Dual-function panel: in overlapping sentences, one panel performs two narrative functions. A panel may, for example, serve as the Release of one sentence and also the Orienter, Establisher, or Initial of the next. Or an Orienter may serve as the Establisher of an interrupted sentence that initializes tension later.

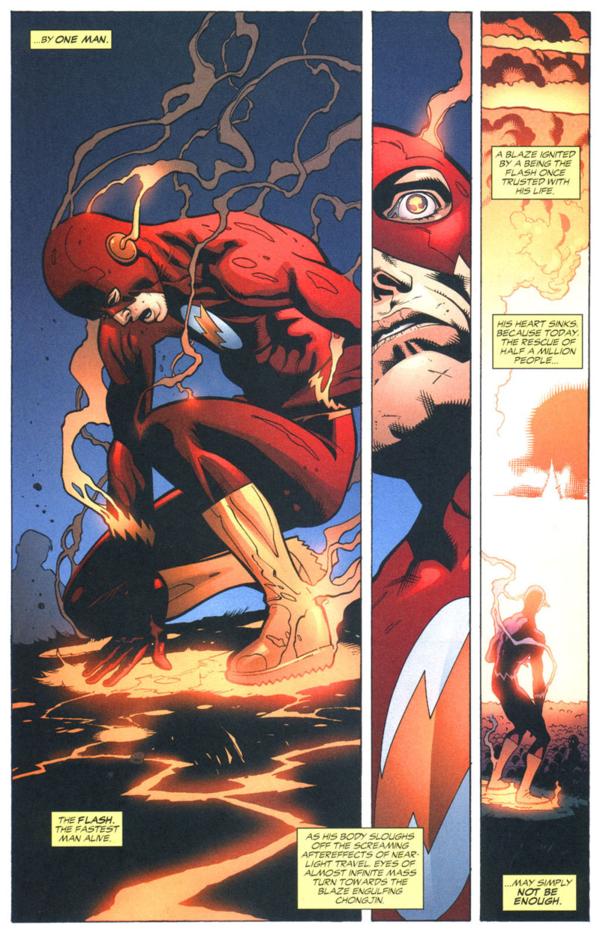

Sentence Layout: the relationship of visual sentences to pages.

Page sentence: a sentence that begins with the page’s first panel and ends with the page’s final panel.

Multi–page sentence: a sentence that extends beyond one page.

End stop: a page and a visual sentence end simultaneously.

Enjambed: a page ends before the visual sentence ends, also called a visual cliff-hanger.

This is all awfully abstract, so let me give specific examples from The Walking Dead again.

Robert Kirkman and Tony Moore like enjambment. Their first issue includes several cliff-hangers. The bottom row of page five begins with an Establisher (introducing the door to the already established figure of Rick), is followed by an Initial panel (Rick removes the piece of wood holding the door closed), and ends with a Peak (Rick is opening the door).

But the Release only appears after turning to page six. That full-page panel is also a dual-function panel because it serves as the Establisher (introducing the zombies to the already established Rick) for the next, overlapping sentence.

The turn from page nine to ten is similar. The first panel in the bottom row of page nine is an Establisher (Rick and the bicycle), followed by the page-ending Peak of Rick’s shocked reaction. The top of page ten provides the Release (we finally see what he sees).

A similar grammatical pattern repeats on pages thirteen and fourteen. The first panel in the bottom row of thirteen is an Orienter. The second is an Establisher (Rick’s face seems to be reacting to something, a sound presumably), and the last panel is an Initial. Turn the page, and there’s the Peak.

The visual grammar also shows that cliff-hangers only work on the final panel of a two-page spread, in order to prevent a reader’s eye from skimming to the critical image prematurely (which happens in my arrangements above).

Also, Moore and Kirkman don’t always enjamb their visual sentences. Page one, for instance, ends on a Peak. The page also begins with an Initial, followed by four Prolongation panels. Page one is a complete page sentence, both beginning and ending on a single page.

Instead of a Release, the next page begins with an Orienter (Rick in his hospital room) for the next visual sentence, which does not overlap.

In terms of interrupted sentences, page ten begins a new visual sentence with the top Establisher (introducing the bicycle zombie to the already established Rick), followed by two Initials (Rick and the zombie interact) in the second. The bottom row begins with two Prolongations, followed by a Peak (Rick’s tear) and a Release (the zombie closes its mouth).

The visual sentence appears to have ended when the next page begins a new sentence with no further interaction between Rick and the zombie. So page ten reads as a complete page sentence, until the bottom of page twenty-three continues the interaction with a Prolongation panel, retroactively showing that the visual sentence was interrupted.

Page twenty-four provides a new Peak (Rick shoots the zombie), followed by two Release panels (Rick looking down, the zombie with a bullet hole in its forehead).

Rick’s tear is also a Prolongation of his tear on page ten, an additional overlapping sentence that reaches its Peak in the next panel when Rick wipes the tear away. The final three panels are Releases. They’re also their own overlapping, three-panel sentence: Initial (Rick and the car), Peak (Rick gets into the car), and Release (car has driven off).

,

,