Asterios Polyp takes an impeccable sense of visual design and layer upon layer of sophisticated allusion to tell a clichéd, tedious, poorly imagined, ruthlessly uninsightful story. It’s like listening to a musically brilliant opera with the book taken directly from a TV movie of the week, or (to take an analogy perhaps closer to my heart) listening to classic Slayer perform a John Updike novel. You can’t but be impressed by the technical skill and control…but it’s hard not to feel that, skill and control notwithstanding, a person who could expend such time, energy, and passion on such vapid idiocy must be, on some level, a fool.

Of course, with a book this intricate and complicated, it’s always possible that the person who doesn’t get it is the fool. I know what I’m supposed to do with this book; I’m supposed to start googling all the names that have flagrant double-meanings; I’m supposed to read and reread looking for connections, following up secret paths. How is the theme of doubling worked through the book? How do the different styles link to different moods and themes? Why does the guy who pokes out Asterios’ eyes at the end seem to recognize him? When exactly did Asterios give up smoking and what does it mean?

I figured out a few of these answers despite myself — but, man, overall, I so don’t care. And I don’t care because, with all the twists and turns and clever games and beautiful drawings, this is, at bottom, a character study, and Mazzucchelli’s characters are all as tediously second-hand and tired as his designs are inventive and new. Asterios Polyp, the character, walks out of the massive towering edifice of literary fiction via rote Hollywoodization, and he’s as utterly devoid of interest as he was the first thousand times I saw him. Hey, look, it’s a Successful Professor Whose Intellectualism Has Disconnected Him From Life. And there’s his younger, also brilliant, but more tentative wife — and…wait! He’s driving her away through his callous self-absorption! Didn’t see that coming. And now he’s undertaking a spiritual journey which involves interacting with common people and/or ethnic minorities! And, look, he learns his lesson and spiritual renewal is his — and happy, happy love! Yay! The end. And if I want to see it all happen again, I can just rent The World According to Garp.

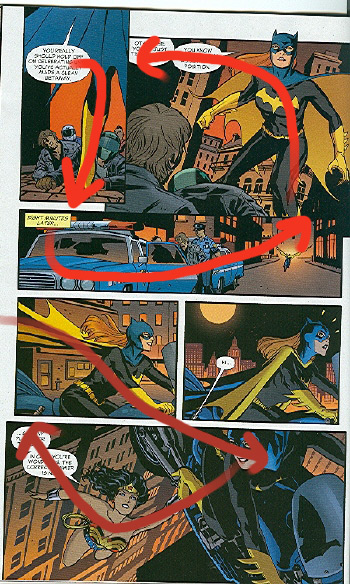

I don’t know. Here are a couple of moments of emblematic shittiness.

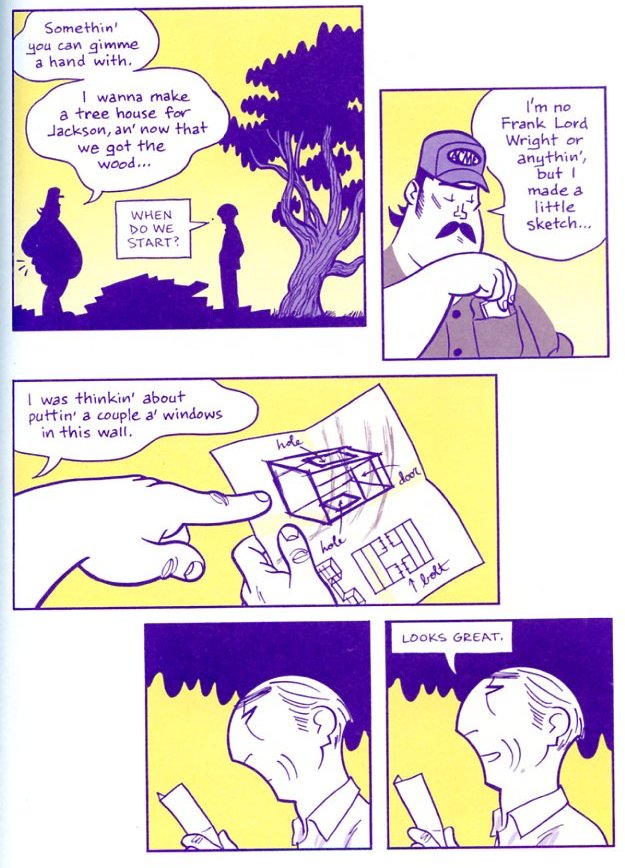

That’s our hero, Asterios Polyp, the great snobbish architect who has never built a house, committing himself to help his working-class boss and landlord build a rickety little treehouse for said boss’ adorable son. Can you savor the gentle irony? Do you feel the tear in your eye? Can you hear the inspirational music from various Kevin Costner vehicles welling up to play over the heartwarming montage?

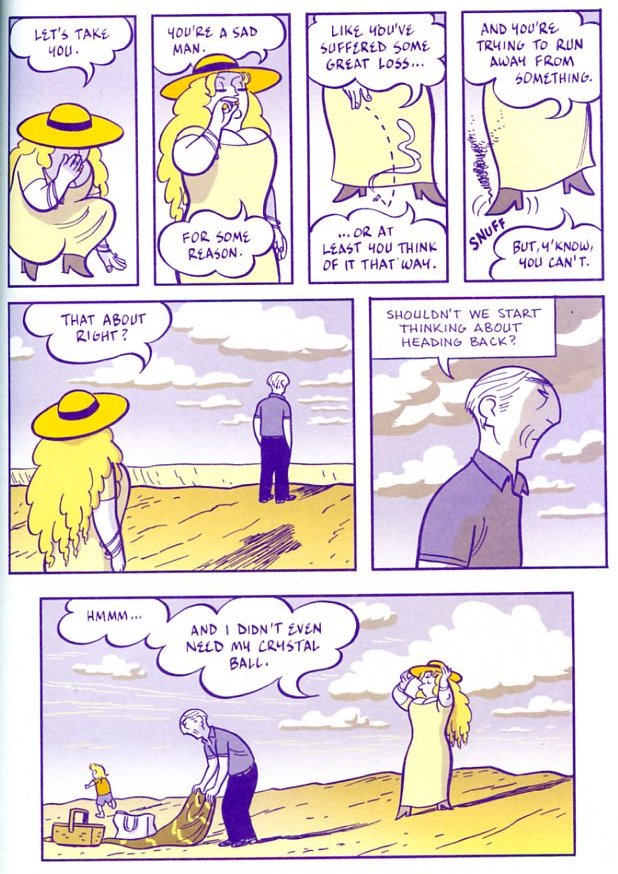

Here’s the boss’ wife, who is into new age nonsense (which we shouldn’t just reject as nonsense because we’ve already been informed that too much rationality is bad bad bad) looking deep into Asterios’ soul and seeing the wounded longing therein. It’s like his heart is just like that giant hole in the ground they looked at a few pages ago, which is a big ironic irony, because Asterios’ heart isn’t a hole at all. How could it be when he got it spackled over with moments of trenchant revelation borrowed from every half-assed rom-com script of the past quarter century?

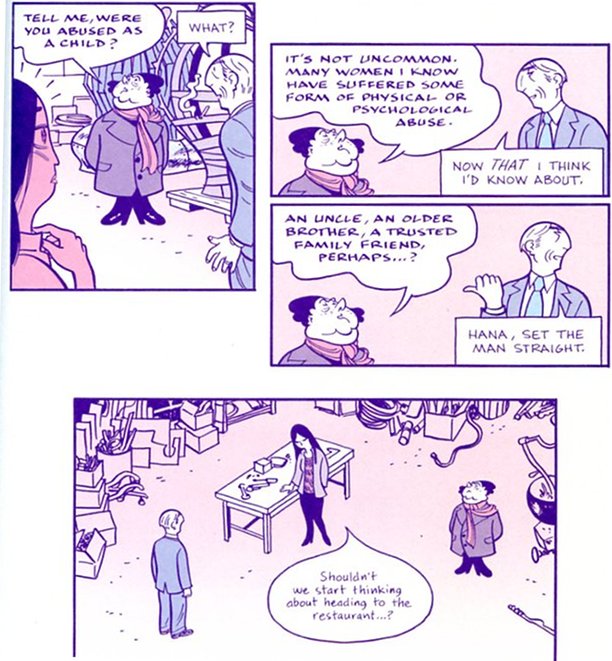

Look! His wife is the victim of sexual abuse! That adds emotional depth, doesn’t it! Hey, this book is really about something, damn it!

Matthias Wivel suggests that the story appears “reductive” because Mazzucchelli leaves out most of the connections; we don’t learn more about Hana and Asterios’ relationship because the point is that we’re to fill it in ourselves — figuring out the spaces in the architectual plan for ourselves. It’s a generous reading, and may well be what Mazzucchelli had in mind. The problem is that the plot and characters he’s given us — the frame in which we are to perceive the spaces — have little of genius, or even elegance. Instead, what he has erected is made out of shoddy, second-hand, thoroughly pissed upon fragments of mediocre pop culture detritus. Which is to say, the problem I have with Asterios Polyp is not, alas, that Mazzucchelli doesn’t give me enough. He gives me plenty.

__________________

This is the first post in a roundtable on Asterios Polyp. Derik Badman will weigh in tomorrow,(He’s now done so) and we’ll have various other Utilitarians and guests posting through next Monday.

Update: You can read the whole roundtable so far here.