We’ve got some changes coming to HU in the near-to-mid-term. More about those presently…but to start with, I think I’m going to put this feature mercifully to sleep. It’s been fun playing at being a dj, but all good things, etc. etc. Thanks to all the folks who downloaded and commented. You can still get all the earlier playlists for the forseeable future here.

Dyspeptic Ouroboros: Cocteau against Ware

The Criterion Collection DVD of Jean Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet contains a transcript of a lecture given by Cocteau in January of 1932 at the Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier, on the occasion of the film’s premiere there. Cocteau begins by talking about critics.

First of all, I will give you an example of praise and of reprimand that I received. Here is the praise. It comes from a woman who works for me. She asked me for tickets to the film, and I was foolish enough to fear her presence. I said to myself: “After she has seen the film, she won’t want to work for me.” But this is how she thanked me: “I saw your film. It’s an hour spent in another world.” That’s good praise, isn’t it?

And now the reprimand, from an American critic. He reproaches me for using film as a sacred and lasting medium, like a painting or a book. He does not believe that filmmaking is an inferior art, but he believes, and quite rightly, that a reel goes quickly, that the public are looking above all for relaxation, that film is fragile and that it is pretentious to express the power of one’s soul by such ephemeral and delicate means, that Charlie Chaplin’s or Buster Keaton’s first films can only be seen on very rare and badly spoiled prints. I add that the cinema is making daily progress and that eventually films that we consider marvelous today will soon be forgotten because of new dimensions and color. This is true. But for four weeks this film has been shown to audiences who have been so attentive, so eager, and so warm, that I wonder after all if there is not an anonymous public who are looking for more than relaxation in the cinema. (This is followed by several hundred words about the film, demonstrating that it is more than relaxation. )

Contrast Cocteau’s response with Chris Ware’s letter about the issue of Imp devoted to his work (published in the subsequent issue).

You’ve done what most critics, I think, find the most difficult – writing about something you don’t seem to hate, which, to me, is the only useful service that “writing about writing” can perform. You write from the vista of someone who knows what art is “for” – that it’s not a means of “expressing ideas,” or explicating “theories,” but a way of creating a life or a sympathetic world for the mind to go to, however stupid that sounds. Fortunately you’re too good a writer to be a critic; in other words, you seem to have a real sense of what it is to be alive and desperate (one and the same, I think.)

Both reactions are, at root, comparisons of praise with reprimand. Yet, unlike Ware, Cocteau apparently finds the reprimand more interesting than the praise. It is noteworthy that the praise Cocteau receives from his female colleague – and mostly dismisses as a kind compliment – is virtually identical to Ware’s stated purpose for art. It is even more noteworthy that Ware’s ideal is so limited in scope that it is entirely inadequate to describe Cocteau’s proto-Surrealist film, which he indicated was created as “a vehicle for poetry – whether it is used as such or not.”

Of course, perhaps Ware was only trying to be nice to the guy who devoted a whole issue of a magazine to him. There is something a little over-the-top about his phrasing. I try to give him the benefit of the doubt even though that letter put such a bad taste in my mouth that I think of it every single time I see the name ‘Chris Ware,’ and it casts a shadow over my appreciation of his work. I’m almost convinced that deep down he actually does agree with himself – is it possible that he really is actually as insecure as his self-presentation? – but I’m willing to be dissuaded.

As published, though, Ware’s letter voices incredibly facile positions on the purpose and value of criticism and art, stating (in opposition not only to Cocteau but even to Gerry Alanguilan) that “writing about writing” can serve no useful purpose other than to praise. (He at least has the sense not to use the word “criticism” in this context.) The letter implies not only that Ware feels he has nothing to learn from critique but that critics who dissent with the Vision of the Artist are somehow bad, not “good writers,” dry and dessicated and less-than alive. This is an evisceration of the existence of criticism, exiling “writing about writing” to the commodity function of marketing and “Comics Appreciation 101” for books that reviewers like.

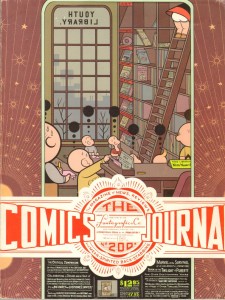

Unfortunately, Ware’s cover for TCJ 200, which also touches on this theme, only gives a little evidence in his defense: his library shelf appears to be a stack ranking of comics “genres,” with pornography and criticism at the bottom, and Art at the top – but nothing on the shelf.

The page is at least slightly ambiguous: there’s really nothing that mandates the shelf be read as a hierarchy rather than a pyramid with criticism and pornography as comics’ foundational pillars. It’s a very open depiction with both interpretations in play. Against the letter’s statement that art is not for “expressing ideas,” the cover expresses plenty of ideas: the juxtaposition of the “youth library” with a setting that is obviously adult (the high ladder, the call slips for closed stacks, the pornography); the ambiguous hierarchy/pyramid itself; the absence of anything much on the “art” shelf; the blurring of age – the cartoon characters depicted are all small children, but they’re behaving like adolescent boys, filling out call slips so Nancy will climb the ladder and they can see up her skirt –; and the resultant indictment of comics fandom and subject matter as stunted and age-inappropriate juvenilia. (Irrelevant aside: the periods in the window and on all of the signs really bug me.)

Yet despite that pretty interesting cluster of ideas, the blunt, indiscriminately ironic tone undermines them by flattening any possible value distinctions. That works strongly against any optimistic interpretation of Ware’s point. Gary Groth in the psychiatric help box is the most honest bit of the page, which verges past Ware’s routine self-deprecation into a scathing self-loathing that reaches beyond the individual to the group. This Ware would only join a club that would have him as a member so he could mock them for their bad taste. It is only funny if one has infinite patience with self-awareness as an excuse. Unless one gives Ware the benefit of the doubt to start with, this panel exudes little more than anger and contempt.

So is the letter too just another example of Ware’s incessant clanging self-deprecation? “My art expresses ideas, so it doesn’t quite measure up to the best purpose of art”? I don’t really think that’s the case.

Ideas take many forms, including images and certainly there’s nothing wrong with expression. The use of art by individuals to express themselves is of time-tested value. Ware’s letter elides the fact that his stated purpose, the “creation of a life or a sympathetic world for the mind to go to,” involves almost exclusively the expression of ideas about that life/world, despite his rejection of ideas as fair game. The letter’s point, though, is prioritizing the evocative experience of a visual “place” over the cerebral experience of ideas or theories, and Ware is far better at evocation than he is at ideas and theories.

So I think his art is consistent with his theory of art in the letter. Despite the frequent self-deprecation, he doesn’t really need praise artistically. He is perfectly well aware of what he does well. He rarely sets himself artistic tasks he cannot execute flawlessly.

More often than not, complexity in Ware’s drawing derives from the intricate realization and juxtaposition of ideas on his carefully crafted pages rather than from a complex interplay among the ideas themselves that is then, subsequently, represented on the page in an equally complex way. The repetitiveness of his aesthetic and the relentlessness of his irony further limit the range of conceptual material available to a critic. Although it’s possible to interpret the TCJ cover as ambivalent about criticism, the hint of ambiguity is just that – a hint. Ware does not tackle the layered ways in which the ideas interact. The concepts consequently never mature into a meaningful new insight: the piece is a meaningful representation of very familiar old insights. Overall the cover is smart, but not much more substantive conceptually than the best editorial cartoons. Unfortunately, this is often true for Ware’s other work as well.

Ware’s rejection of “ideas” and “theory” thus feels tactical, veiling the extent to which his art is not well served by analytic criticism, even of the most explicatory ilk. Ideas in Ware’s art lose a great deal when they are articulated. Spelled out in prose, without the grace of his talent for imagery, they lose their “life” and become bland. Since one of criticism’s essential actions is to articulate the interplay of ideas and hold it up to scrutiny, Ware’s work cannot consistently stand up against criticism that does not appreciate it. At the very least the analysis must appreciate his psychological angle – the particular voicing of interior life against exterior pressures that counts as story in much of his work. Praise that “gets” him can serve as explication for less savvy readers, but criticism that rejects him deflates his project entirely.

In the counterexample, Cocteau explained his film by embracing the very transience that had been leveled against him as a criticism. This was axiomatic for Cocteau: “listen carefully to criticisms made of your work,” he advised artists. “Note just what it is about your work that critics don’t like – then cultivate it. That’s the only part of your work that’s individual and worth keeping.” Even his stance toward criticism itself stands up to the scrutiny of articulation, as he was surely only half-serious: he wrote criticism himself, he counted among his friends the art critics Andre Salmon and Henri-Pierre Roche, and he was acquainted with Apollinaire (who, alongside Sam Delany, Salman Rushdie and Joan Didion, illuminates why Ware’s phrase “too good a writer to be a critic” is mere ignorance).

Ware’s letter, with its casually passive-aggressive muzzling of critique, is the very opposite of “listening carefully”: it’s a kinder, gentler playground bullying of the class brain. Cocteau’s contrasting approach, rich with confidence, recognizes how the relationship of artist and critic can be that of interlocutors. The conversation may happen in writing and the artist and critic may never actually speak to each other face to face, but criticism as such is inherently fecund. Critics model ways of talking back to art, and talking back increases and vitalizes the relationships among any given art object, the people who engage with it, and the culture in which it operates. It is precisely the thing that moves art beyond being merely the “expression” of an artist, toward a more ambitious function as a site for cultural engagement and debate. Critics and readers are also interlocutors; the critic is thus interfacial, and this triangulated conversation in many ways demarcates the public sphere. Artists who reject this conversation show contempt for their readers. They are, in contrast to Ware’s assertion, far more interested in self-expression than in any other purpose for art.

What I find most disheartening is not this disingenuousness with regards to expression, not that Ware discourages writers from writing criticism (we are a hardy bunch), but that he encourages contempt of writers who do write criticism and contempt of the modes of thought modeled by criticism by any readers and artists who pay attention to the opinions of Chris Ware. Regardless of his motives, Ware’s letter throws his not-inconsiderable weight behind an approach to art – and of engagement with art – that invalidates and forecloses thoughtful, cerebral engagement.

This kind of careless anti-intellectualism is not a philosophy of criticism. It shuts down several questions that are utterly essential for comics criticism: whether the existing critical toolkit, with its heavy emphasis on prose explication of illustrative examples, is in any way sufficient to capture the native complexity of comics, whether viable alternatives exist, and to what extent and in what ways it matters that translation to prose evacuates the complexity of many comics texts. (The fact that explication of Clowes’s work does not evacuate his complexity is an important argument against the knee-jerk assertion that complexity in comics is somehow entirely different in kind from that found in literature and film, but the point is surely open to debate.)

Criticism is the correct place to argue the merits of different ways of making conceptual meaning in comics, and that conversation is not really possible in “writing about writing” that attempts nothing beyond praise. But that conversation is absolutely necessary if comics are ever to respond to the challenge Seth articulated in Jeet Heer’s panel: “I guess it is a failing of the culture not to have recognized anything in comics, but it’s also a failing in comics, to have not presented much for them to recognize.”

I said in the beginning of this essay that Ware does not understand what criticism is for, and his cover art, in its typical bleakness and self-deprecation, dramatizes this limitation of his imagination. Criticism is the thing you need before you can have something on Ware’s top shelf, the one labeled Art. The one that, for Ware, is unsurprisingly empty.

Update by Noah: Matthias Wivel has a thoughtful response here. Also, the thread here was getting unwieldy and has been closed out; if you’d like to respond please do so over on the other thread.

Can Comics Be Scary?

Eric B. doesn’t think so. In response to my post on contemporary horror comics, he wrote:

“How’s this for a random unsubstantiated claim:

I don’t think comics can be scary, period. Too small…

too quiet…too temporally static. Never been scared

by any horror comic I’ve read…not a one. Yet…I

can’t watch horror movies–predictable or not–too scary.”

After thinking over the horror comics that I’ve read, I’m forced to agree with him. Even when I enjoyed a horror comic, such as The Walking Dead or some of the earlier Hellblazer comics, I didn’t find them particularly scary.

There’s certainly no way that comics can be scary in the same way that movies are scary. Comics can’t use mysterious noises or creepy music (textual representation of sound is a poor substitute). Also, since movie-goers instinctively understand that the world of the film extends beyond the view of the camera, horror films routinely have their monsters lurk just outside the frame. And they can startle the audience by having the monster (or a fake-scare cat) pop out from outside the camera’s view. In comics, establishing clear spatial relationships from one panel to the next is difficult enough without also having to imply that there’s something lurking off-panel. And the “temporally static” nature of comics makes it impossible to startle readers with anything popping out.

But the greatest advantage that horror movies have over comics has less to due with the technical differences between the media, and more to do with how the average person watches a movie. Over the decades, Hollywood and the theater chains trained audiences to watch movies in a certain way: you turn out the lights, ignore everyone else in the room, and stop thinking. Movie-goers become completely immersed in the narrative, and horror films exploit this immersion like no other genre. As an example, when the soon-to-be victim wanders through a dark hall to investigate a strange sound, the camera forces the viewer to follow the victim and vicariously experience everything they see and hear.

Comics simply can’t offer the same degree of narrative immersion. For starters, reading comics with the lights off is rather difficult. Also, immersion requires a passive mind, and comic readers can never turn their brains completely off. Even the most moronic superhero title still requires some active thought in order to read the text and interpret the narrative flow between panels. None of this is meant to say that comics can’t be engrossing page-turners, but comic readers generally don’t lose track of reality to the same degree that movie-goers do.

So does this mean that comics can never be scary? To the extent that “scary” refers to the visceral, immediate fears that horror movies deliver so effortlessly, the answer is yes. But if “scary” also encompasses the deeply-rooted fears and common anxieties of the readers, then perhaps there is some hope for horror comics.

Novels have many of the same technical limitations as comics, and yet there is a long literary tradition of horror dating back to Frankenstein, and horror writers such as Stephen King continue to enjoy great success. Obviously, a medium consisting entirely of text could never scare readers with startling noises or monsters jumping out of closets. So novelists tend to downplay immediate physical terror and focus on social fears and unnerving concepts, particularly of a religious or existential nature. Frankenstein reflected the major anxieties of the Romantic era, particularly the fear of a godless mankind. H.P. Lovecraft scared his readers by envisioning a universe that was essentially hostile. Most ghost stories exploit the fear of death and the the unknowable nature of the afterlife. There’s no reason why comics couldn’t tap into similar social or religious anxieties (and it’s worth noting that the best horror films already do so).

But horror comics have largely failed to measure up to the standards of horror novels. The earliest horror comics like Tales from the Crypt were designed to offer nothing more than the cheapest and shallowest entertainment. Plus, individual comic issues were simply too short to contain a plot with any complexity. And it was always easier to just add more gore than to write a gripping story. The visual element of comics may have also convinced comic creators that their medium had more in common with film than with literature, leading to futile efforts to re-create the thrills of horror movies on the static page.

Comics have the potential to be scary, but it’s a potential that remains unrealized. There is, however, the possibility that my knowledge of horror comics is too limited, so I’ll pose a question to the commenters: have you ever read a scary comic?

Song of the Hanging Sky, vol 2

Yes, gentle reader, I read the next volume. The story picks up three years after the last volume. During the interim, things have been pretty quiet. The doctor Jack continues to live with his adopted child-aged father and the bird men tribe. However, the shaman River has disappeared and one of the tribe members, Horn, has become increasingly sick and has disturbing visions about the Day of Destruction.

This is, hands down, the most confusing manga I have ever read. Well, OK, maybe not quite as confusing as Angel Sanctuary and it’s multi-personality no glossary messiness, but close.

Here are some notes that I took while reading.

Man=child

Hello=boy

Another River is not a man

Cherry=soldier

There’s a desperately needed, somewhat helpful cast of characters, but it’s not enough. Man, for instance, is included there under the name No Man. If you have someone staring at a big scary thing, saying “Man,” is your first thought that this is someone’s name? The name of a baby at that? Because it wasn’t mine.

Which brings us to the other big problem. Most of this volume takes place in the past, which means that everyone looks different. They’re also often addressed by their relative nicknames like sis, my older cousin, my nephew. Which would maybe be OK, but the relative in question is often dead in the present. And then there’s the character who is addressed by more than one gender pronoun. The character glossary has this amusing sentence: He has no gender. Um, yeah.

Did I mention that there seem to be two completely different Days of Destruction?

So why struggle through it? The art is lovely and the story is quite interesting. There’s a lot of cool plot going on under all the bizarre name problems, with interesting interpersonal politics and ideas about destiny (can it be changed?) and what honor means and the power of war.

I hesitate to explain the major plot points, because the twists are quite fun, but I think I can add that there is a nice backstory of the chief Fair Cave retelling the story of the clan’s destruction to Jack. The story, such as it is, that happens during the modern day is primarily about the soldier Cherry, a young officer who is wounded in battle. He makes an interesting contrast to the young Hello nee Nuts Peck, who was rescued in a similar way in the previous volume.

I’ll probably succumb and get the next volume, despite the massive translation/confusion problems. I wish they would do something like bold or capitalize the first letter of the names. It’s so puzzling and detracts from an otherwise very fun comic.

The Castafiore Emerald

A while back I discussed some of my reservations about the Tintin books. I found the slapstick precious, the characters caricatured, the art lacking in visceral appeal, and the layouts consistently boring.

Numerous folks stopped by to tell me I didn’t know what I was talking about or (more kindly) to suggest that I should try some of the later Tintin books. In particular, several commenters recommended The Castafiore Emerald.

As it happens, my son has become a little obsessed with Tintin, so I thought I’d use that as an excuse to buy The Castafiore Emerald and see if it changed my opinion of the series. My boy, as expected, loved it…but I still wasn’t convinced.

That isn’t to say that the story is without interest. In fact, it diverges from earlier books in the series in a number of intriguing ways. Herge (according to trusty Wikipedia) was tiring of the series, and wanted to try something new. And what he tried was abandoning the adventure book format. In Castafiore Emeralds, Tintin doesn’t head for any exotic locale (as is the case in almost all the other books in the series), and he doesn’t encounter criminals, danger, or excitement of any sort really. Instead, he participates in a drawing room mystery/farce, in which every crime isn’t, every suspect is innocent, and the only real suspense is how Herge will manage to spin the plot out for a full 62 pages without ever having anything happen.

As a formal exercise, this is undeniably masterful; you only really appreciate Herge’s narrative genius when you see him turn all his tricks back on themselves, so that all the careful foreshadowing ends in blind alleys and the characters spin around and back on themselves, endlessly chasing their own slapstick-bruised backsides.

But as with Herge’s work in general, while I can appreciate the achievement on an abstract level, I can’t love it. Like Herge’s drawing, The Castafiore Emerald is almost too polished — and definitely too pat. You can feel the audible “click” as each false lead is resolved, and you can hear the laugh track rev up as each character is wheeled out (literally in the case of the wheelchair-bound Captain Haddock) to perform their schtick. And throwing in some gypsies so that Tintin can demonstrate his liberal bonafides by not suspecting them of theft…well, let’s just say I wish Herge had resisted the temptation.

Again, my son adores it when Calculus misinterprets what someone told him yet again because he still can’t hear and deaf people are always funny; or when Haddock splutteringly shouts “Billions of blue blistering barnacles” for the umpteenth time, or when the fiftieth person trips over that broken step and falls on their butt. Kids like to see the same joke over and over. And it’s not like I’m totally opposed…but the predictable surprises and even more predictable characters, the preciousness and the bloodlessness, the relentless clockwork perfection of it — it leaves me cold, and kind of irritated. Certainly, if I have to read something to my son, I could do (and have done) a lot worse. His current fascination with the Narnia books is giving me a lot more pleasure than his Tintin kick, though.

Utilitarian Review 4/3/10

We’re going to take a day off tomorrow for the holiday. We’ll be back on Monday.

On HU

This week I talked to artist and critic Bert Stabler about art, criticism, pragmatism, and materialism.

Suat explained why comics will never be as exciting as video games.

Caro explained why this thing she found is comics (and in comments folks speculate on whether or not it might be by William Steig.)

Suat discussed Chester Brown’s gospel adaptations.

And Caro interviewed novelist Jonathan Lethem.

Utilitarians Everywhere

At the Reader I discussed the black metal band Ludicra and women in extreme metal.

The fact that when the women in Ludicra sound like women they’re essentially being used to replace a synthesizer is emblematic of how gender works in extreme metal. Which is to say, it doesn’t work at all. Extreme metal doesn’t care about men and women. It barely cares about bodies. Johnny Rotten howls “I’m not an animal!” and extreme metal responds with a louder and even more hideous howl of indifference. Misanthropy, to say nothing of misogyny, is for the living. Extreme metal’s aggression may sound male on the surface, but a corpse isn’t masculine even if it has a penis. Extreme metal seeks a monstrous oblivion; it uses unrelenting noise to destroy not just the dying animal but also the angel fastened to it. “Teach me to mask the spirit . . . The farce of human bonds / Of dignity and respect,” Shanaman howls. “Let me be the clean white void / The slate . . . the unwritten.” You don’t have genitals when you’re a mask upon a void.

I gave a one-star review to Kath Bloom’s remarkably lame new album over at Madeloud.

I reviewed the new Twilight Graphic Novel on tcj.com.

Other Links

This is a fascinating article about the copyright difficulties of producing a documentary about sampling.

And I enjoyed Erica Friedman’s wrap up of her and her wife’s trip to Japan.

Music For Middle Brow Snobs: Kaptain Death

I’ve been tentatively getting more into death metal recently….

1. Rimfrost — The Black Death (Veraldar Nagli)

2. Testament — Curse of the Legions of Death (The Legacy)

3. Possessed — Death Metal (Seven Churches)

4. Dark Angel — Death Is Certain (Life Is Not) (Darkness Descends)

5. Deicide — Behead the Prophet (No Lord Shall Live)

6. Vader — Flag of Hate (Future of the Past)

7. Vader — Silent Scream (Future of the Past)

8. Entombed — Premature Autopsy (Left Hand Path)

9. Acrostichon — Zombies (Engraved in Black)

10. Decapitated — Visual Delusion (Organic Hallucinosis)

11. Hooded Menace — From Their Confined Slumber (Never Cross the Dead)

12. Apostle of Solitude — Sister Cruel (Last Sunrise)

13. Dark Star — Kaptain America (Dark Star)

14. Pat Benatar — Never Wanna Leave You (Crimes of Passion)

Download Kaptain Death