“The internet is a toilet.” …..Plumb away!

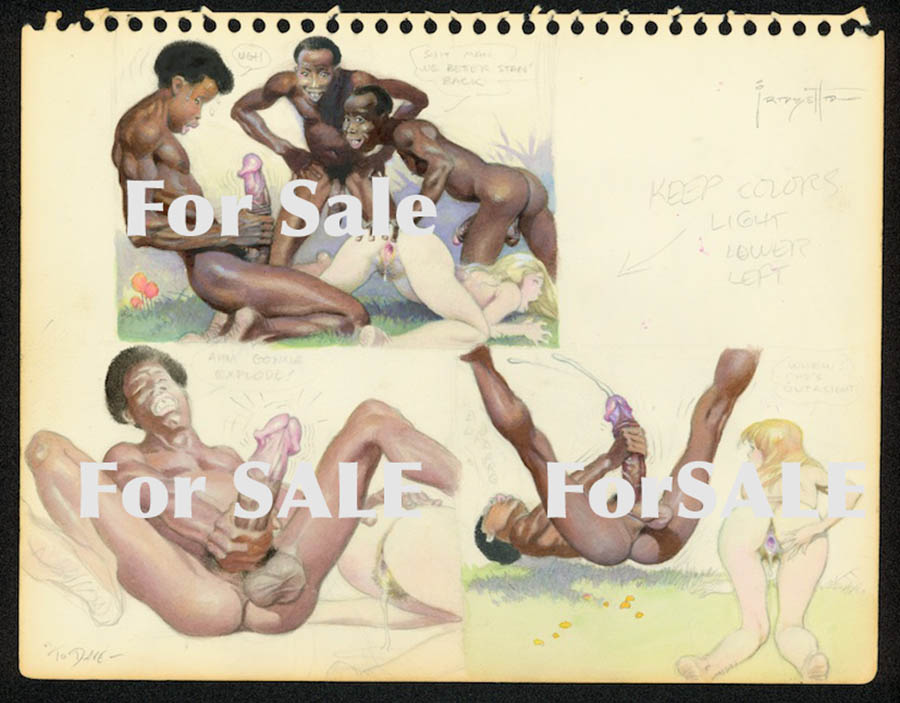

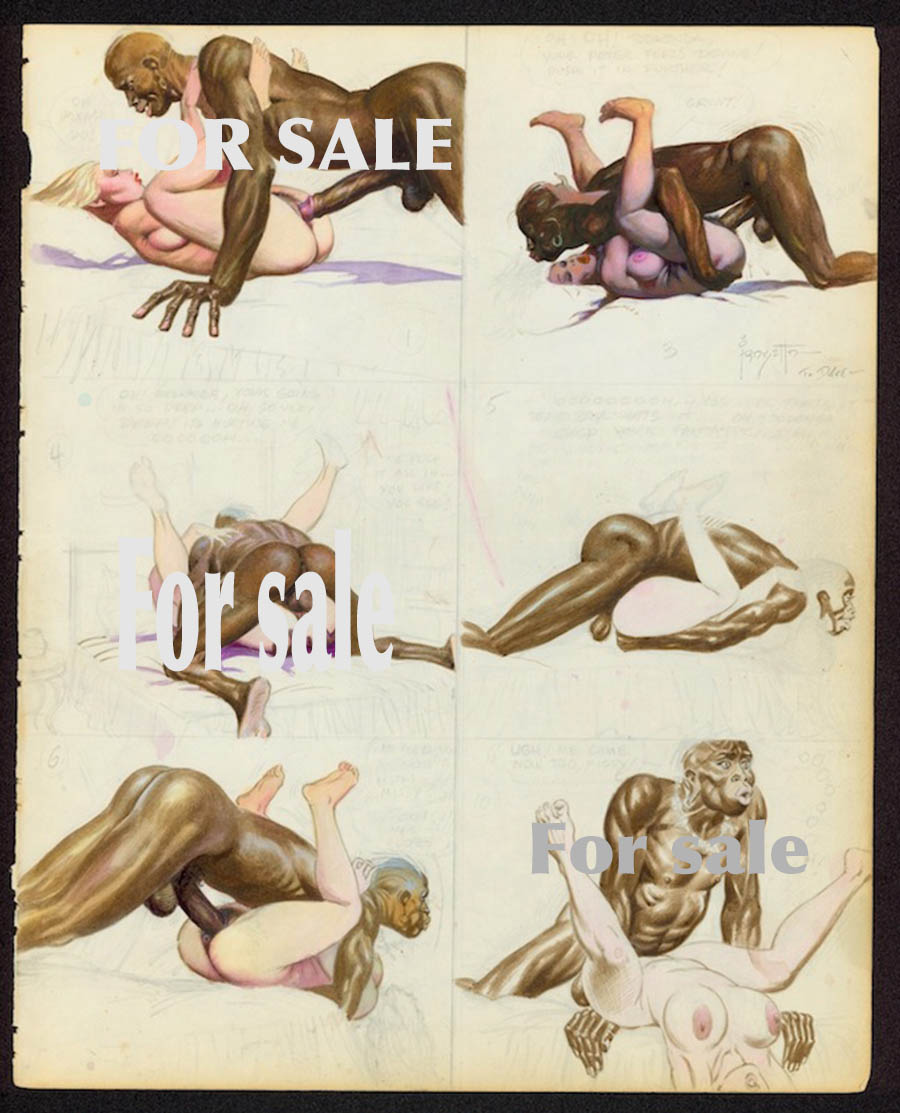

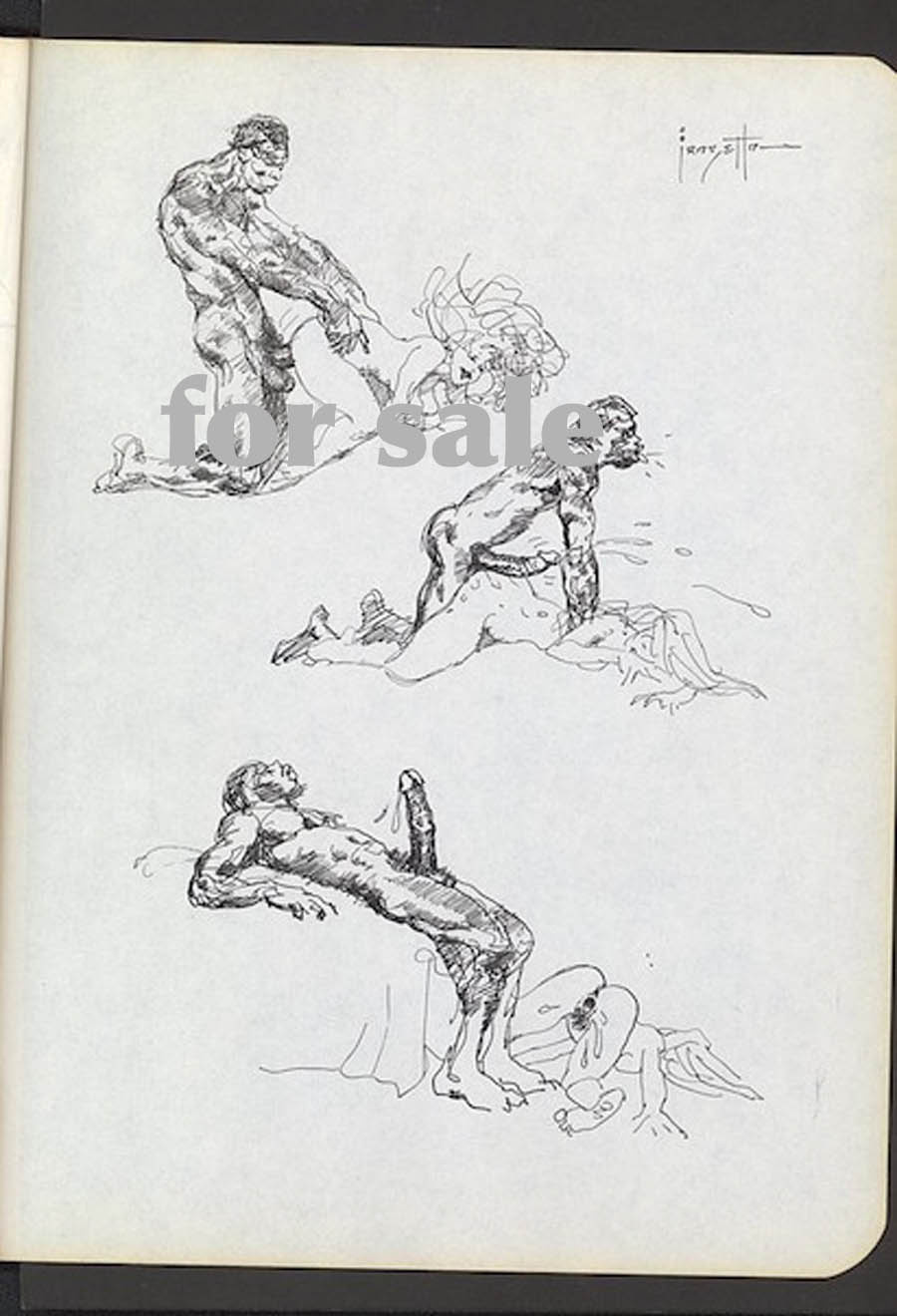

Background: There’s a hugely anticipated Frazetta auction due in early December 2015. Some nudie art could not be included in the printed catalog (and online) on the advice of the auction company and its lawyers. The chattering classes were rife with rumors and speculation. What could possibly be so disgusting that it could be auctioned but not included in the printed catalog? Surely nothing as pathetic as cunnilingus, female ejaculation, or facials. So perhaps bestiality or necrophilia? Don’t those horrible Europeans also sell Crepax doggy art? What’s wrong with that? As it turns out, it was nothing quite so gross, just a “simple” case of white slavery (+/- rape).

I wanted to preserve these on HU since the site is periodically interested in such things. I mean both Frazetta and the obvious.(The below is NSFW, if you hadn’t figured that out already.)

____

The “For Sale” signs were added by Roy Lichtenstein and Edward Ruscha in 1998.

Here’s the description from the blog that first published these images (link is temporary):

“Frank has always had a strong interest, a fetish of sorts, in black sexual stereotypes. Why would he spend so much time extolling the virtue of black sexuality if he disliked blacks? Makes no sense. What is his intent? The joy and delight inherent in sex. One must see the totality of these stories to appreciate fully their intent and idiosyncratic approach. He has other erotic art dealing with just whites, no blacks. A superficial and prosaic understanding is really worthless in appreciating this material.”

I don’t think this statement needs to be dismantled in any sustained fashion except to say that if you think Thomas Jefferson must have liked blacks because he had sex with Sally Hemings, then this art is for you.

My first thought when I saw these newly revealed images was why people needed to see them to realize that Frazetta had real problems with Africans (and perhaps blacks in general). The white slavery/inter-racial trope is a small corner of the porn world and usually presented in the spirit of fun and games; a fetish which Frazetta would no doubt have approved and appreciated. These new images, on the other hand, bring to mind Robert Crumb’s “When the Niggers take over America,” a work which has been interpreted with diminishing amounts of charity in recent years.

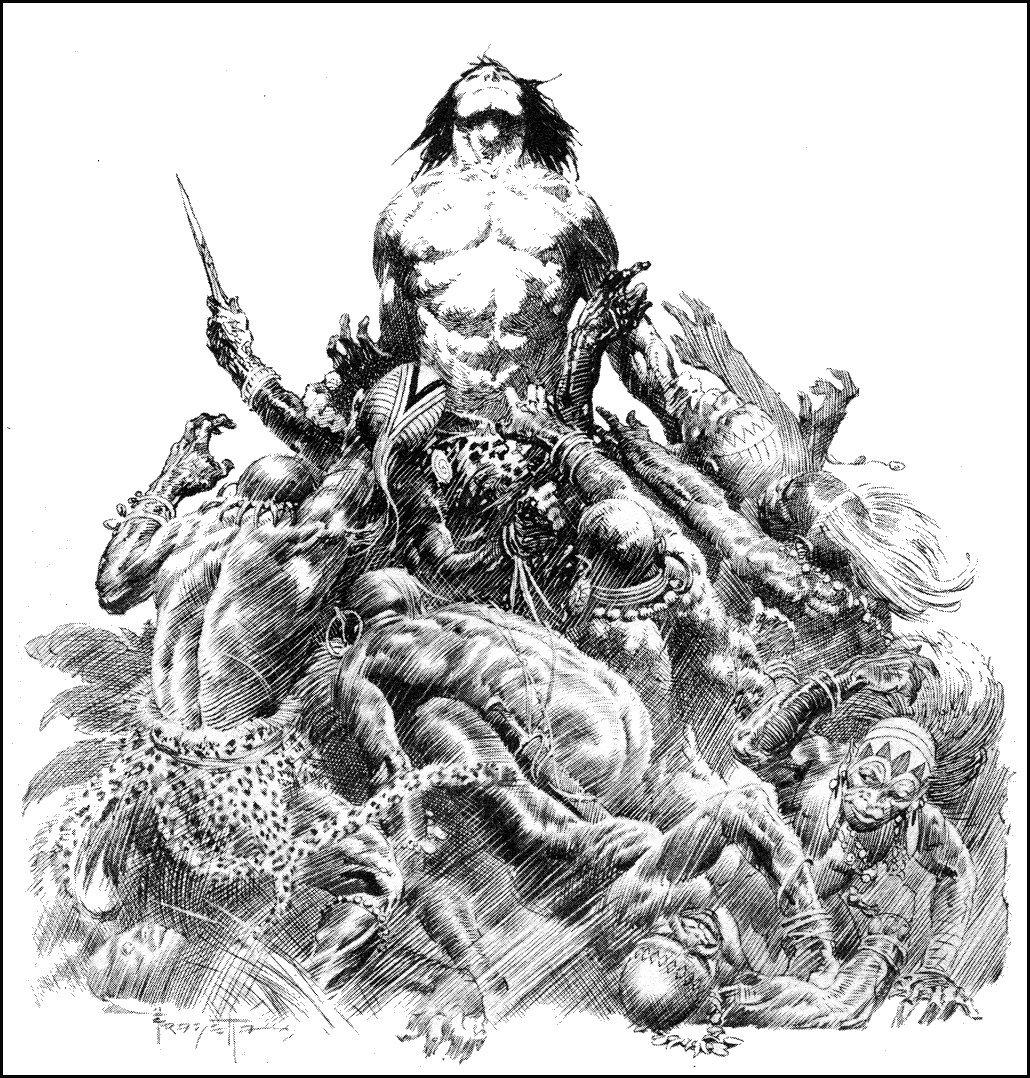

The illustration below, for example, is widely considered one of Frazetta’s greatest pen and ink works.

There is nothing subtle about the content here which makes its wide acceptance altogether more distasteful. The Frazetta “porn” is a shameful business which we can all collectively shake ours heads at but the same worldview was ladled out generously in much of his oeuvre.

The Tarzan of the comics (let’s forget about Burroughs for the moment) was, of course, deeply invested in white supremacy and purity; with the great apes afforded an even greater status than the Africans who appeared in them periodically. Hal Foster certainly couldn’t escape the siren (and, yes, racist) call at the core of the Tarzan narrative when he famously drew the character in the newspapers back in the 30s.

His acolytes like Frazetta could be seen trafficking in similar imagery in the pages of Thun’da towards the latter half of the 20th century. Russ Heath in the story, “Yellow Heat,” is yet another famous exemplar of this trend in adventure and horror comics. If there is any desire to heap praise on the laughable civil rights comics of the EC line, then one can look no further than these comics for their counter examples.

The standard defense for these images is that Africans “really” were that way—in that they really sharpened their teeth and really ate people. And, yes, were generally crowd surfed by white people (metaphorically speaking of course). Presumably, the images on display in Frazetta’s porn stash will be diagnosed as an acute insight into black sexuality or at the very least a liberating moment of self-revelation and self-parody; a plumbing of the very depths of the human soul. On this last point, at least, I think we can all find some space for agreement.

__________

Update: In comments, Frazetta’s images above have been compared to the tradition of Asian erotic temple art of which the most famous example must be the reliefs at Khajuraho. I guess there are worse ways to insult the Indians.