Fact 1: there are women working in the comics industry!

Fact 2: no matter how successful these women are, Marvel will always refer to them as girls.

Girl Comics #1 (of 3)

Girl Comics is the latest anthology mini-series published by Marvel. The last one, Strange Tales, was a collection of short stories produced by independent creators and featuring Marvel characters. This time around, the gimmick is that everyone (writer, artist, letterer, and editor) involved in the comic’s production is a woman. At first glance, this seems to be a clever move indicating that Marvel is no longer a (fan) boy’s club. Though I can’t resist noting that the bosses of all these women, including the editor-in-chief and the publisher, are men. And I’m not sure assigning all these women to a niche market anthology series qualifies as a great step forward in gender equality. But everyone starts with baby steps. Maybe in a few more years, Marvel will let a girl write X-Men.

I’d also point out that Girl Comics is part of a broader effort by Marvel to attract female readers. 2010 is supposed to be the year of Marvel Women (they have their own calendar), and several new female-focused series are debuting over the next few months, such as Heralds, Black Widow, and the horrendously named Her-oes. What are potential female readers supposed to make of all this? Honestly, I’m not sure. If they’re not already Marvel fans, I doubt women are going to start flocking to comic shops to buy Girl Comics just because it has half a dozen female pencilers. And they’re definitely not going to buy Her-oes, regardless of how loudly Marvel hypes its C-list heroines.

But I’ll stop being such a downer, because the content in Girl Comics is halfway decent. In my review of Strange Tales, I complained that the shortness of each tale (about 4 pages max) left little room for storytelling. As a result, most the entries were just one-note joke strips ranging from awful to mildly amusing. The average length of a story in Girl Comics is about 7 pages, which doesn’t sound like a huge increase, but it actually does make a difference. The stories are still brief, but they contain actual plots. In between the main stories there are shorter gag strips as in Strange Tales, as well as double-page biographies of women who’ve worked for Marvel over the years (including Stan Lee’s secretary!).

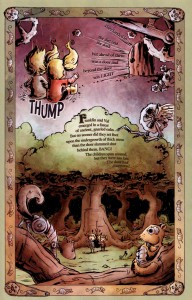

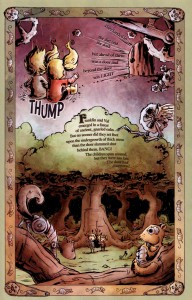

As with most anthologies, the quality of each story varies. Easily the best of the bunch is “Clockwork Nightmare,” by Robin Furth and Agnes Garbowska. The story is an homage to both “Alice in Wonderland” and “Hansel and Gretel,” with Franklin and Valeria Richards (the children of Mr. Fantastic and the Invisible Woman) in the roles of the lost children. The plot is simple: Franklin and Valeria are playing with one of Mr. Fantastic’s inventions and become trapped in an alternate dimension. But it’s embellished by art that’s equal parts charming and brilliant. Garbowska toys with the basic mechanics of a comic in ways that I would never expect to see in a Marvel title. For example, when Franklin and Valeria are in the real world (that is, the superhero world) their dialogue is presented in standard word balloons, and the panel layout is thoroughly conventional.

But once the two children get sucked into the clockwork universe, the word balloons disappear and all the text, including dialogue, is presented as prose within the image itself. The clear lettering by Kristen Ferretti ensures that the text remains legible, even on pages where the script is too dense for its own good. Traditional panel layout also vanishes, and instead the story progresses vertically downward on each page, in a manner deliberately reminiscent of an illustrated children’s book.

When the children escape the clockwork universe, “reality” is restored, along with word balloons and panel gutters. The shifting between two different formal approaches highlights the breadth of the comics medium and the ease with which form can be altered to match the nature of the story.

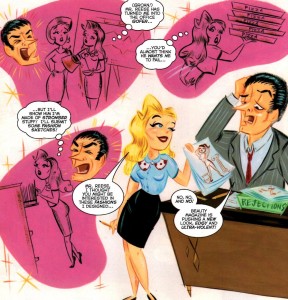

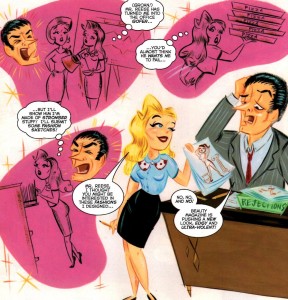

Another great entry is the Venus story by Trina Robbins and Stephanie Buscema. For those of you who aren’t comics historians, Venus, the literal Goddess of Love, was the star of a romantic adventure comic that Marvel (or back then, Timely) published in the 1940s. Trina Robbins’ script is suitably outlandish, with Venus engaging in a wager with Hercules to prove that love can conquer all. So naturally she disguises herself as a mortal woman and gets a job at a beauty magazine but her boss only wants to produce ultra-violent fashions so she helps a model from an oppressive Middle Eastern regime find love and escape satyrs dressed as ghosts and … it’s just fantastically bizarre. Buscema’s artwork, which is influenced by commercial art and design from the 1960s, is charming in its own right, and it captures the zany, retro spirit of the plot.

Unfortunately, the other main stories in the anthology are nowhere near as entertaining. G. Willow Wilson and Ming Doyle turn in an action story featuring the X-Men’s Nightcrawler in a German cabaret. It’s an amusing concept for readers who are familiar with the character, but Wilson’s script never goes anywhere with the idea, and instead she focuses on an insubstantial fight. And while Doyle’s artwork is attractive, fight scenes are not her strong point.

Devin Grayson and Emma Rios tell a story about Cyclops, Jean Grey, and Wolverine, the premier love triangle of the X-Men. Grayson’s script has some decent ideas. It playfully explores Cyclop’s insecurity regarding Jean’s affection for Wolverine, and how that insecurity continuously ruins the psychic dream world that Cyclops and Jean could otherwise share. But the story probably won’t make much sense, or have any emotional effect, unless the reader is already familiar with the characters and their history. Plus, while Emma Rios has an appealing mainstream style, there’s nothing particularly noteworthy about the art.

The weakest entry was a brief Punisher story written by Valerie D’Orazio (best known for her blog, Occasional Superheroine). I would describe the plot as a mix between a typical Punisher comic and “To Catch a Predator.”

Obviously, the joke is that the Punisher is masquerading as a young girl online so he can lure sexual predators into a trap. The story is a little creepy, and seem out of place alongside the more light-hearted content in the rest of Girl Comics. But the real problem with D’Orazio’s script is that it just goes on for too long. At best, it works as a single page strip, but it’s extended for three more pages until finally lurching to the predictable conclusion. Nikki Cook’s art conveys the narrative in an clear manner, but there’s so little content to the story that there isn’t anything else for the art to do.

The main stories in Girl Comics #1 are a mixed bag, but I enjoyed a couple of them far more than I expected, and when judged together they’re superior to the stories in Strange Tales. While the creators in Strange Tales were content to throw together a few gags that mocked popular superheroes, at least some of the creators in Girl Comics were trying to produce great short stories that happened to feature Marvel characters. As I mentioned above, there are also short comedy strips between the main stories and biographies of women who worked for Marvel. The former are forgettable, the latter might be of interest to historians of the comic book industry. Overall, Girl Comics is a very uneven book, but parts of it are good enough that I’ll give the next issue a try.