I grew up thinking of DC and Marvel as rival teams in a vast, superpowered Olympics. Who’s stronger, Superman or Thor? Who’s faster, Quicksilver or Flash? Every spin of the comics rack was a new exhibition in their never-ending face-off.

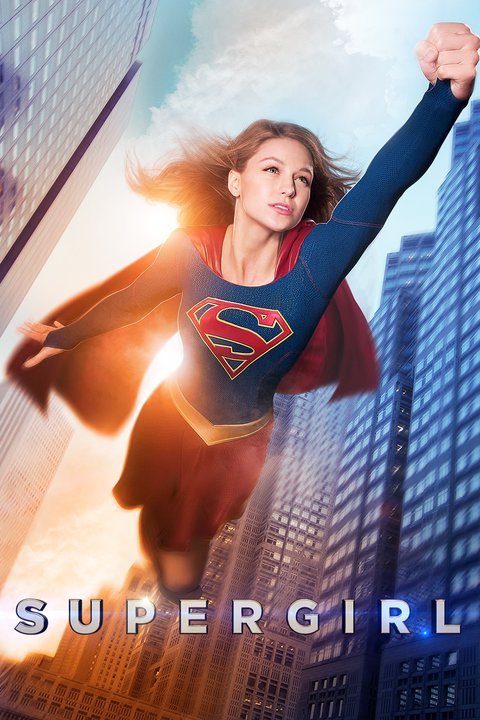

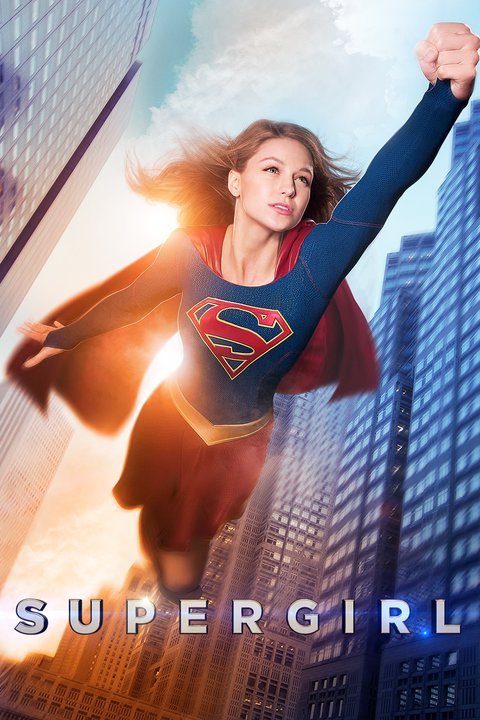

That’s why new Supergirl show is such a game-changer. Sure, the character has been around since 1949 (though that “Supergirl” was Queen Lucy from the Latin American kingdom of Borgonia, not Kara Zor-El, Superman’s cousin). Melissa Benoist’s Supergirl looks perfectly fun too. I’m even happy to see CBS back in the superheroine business. They rescued Wonder Woman from cancellation in 1976, before introducing the first live-action incarnations of the very male Marvel pantheon: Spider-Man, Captain America, Doctor Strange, Daredevil, and, one of the most successful superhero shows ever, The Incredible Hulk. We’ll see if Supergirl survives five seasons too.

But aside from its team-switching network, it’s the show’s timeslot that throws the biggest red flag on the DC-Marvel playing field. Mondays at 8:00? That’s when the pre-Batman series Gotham airs. I would shout FOUL! But can you foul your own teammate? Supergirl and Batman, they’re both DC regulars. So it must be an off-sides penalty? One of them should be lining up Tuesdays at 9:00 to go head-to-head with Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., right?

Actually, no. Supergirl is CBS, Gotham is Fox. Neither networks cares about comic book rivalries. Their playing field is primetime. The CW airs a pair of Justice League characters too, Flash and Arrow, plus soon Atom, Hawkgirl and a few other second-stringers in their third DC-licensed show, Legends of Tomorrow. If CBS preferred any of those time slots, they’d land Supergirl there instead. Worse, Warner Brothers has a Flash film scheduled for a 2018 release—but it will be staring Ezra Miller, not CW actor Grant Gustin. If Green Arrow makes into 2019’s Justice League Part Two, Stephen Amell can expect to be benched too.

These aren’t just facelifts. The TV and film versions of DC superheroes are different people living in different worlds. Christopher Nolan had barely completed his Batman trilogy in 2012 when Warner Brothers started their Ben Affleck reboot. Supergirl earned her pilot because of her cousin’s box office success in 2013’s Man of Steel. But that’s not the same Superman. Look at Jimmy Olsen. The difference is literally black and white. He’s played by Mehcad Brooks on TV, and Rebecca Buller in the film (okay, they changed the female Jimmy to Lana Lang, but still).

Compare that no-rules rulebook to Marvel’s team-player strategy. In addition to the Avengers, the Marvel Cinematic Universe includes five solo franchises (Ant-Man, Thor, Captain America, Iron Man, Hulk), four Netflix shows (Daredevil, Jessica Jones, Iron Fist, Luke Cage), and two ABC shows (Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., Agent Carter). And they’re all jigsaws pieces in a single, unified puzzle.

When the Netflix Matt Murdock talks about uptown superheroes, he doesn’t just mean Thor, Iron Man and Captain America; he means the Chris Hemsworth, Robert Downey Jr., and Chris Evans incarnations of Thor, Iron Man and Captain America. Peggy Carter began in the first Captain American film in 2011, before spun-off in her own TV show last year, and she appeared in the first scene of this summer’s Ant-Man, and she’ll appear again for her own funeral in Captain America 3 next spring.

Imagine the galaxy-sized migraines involved in keeping all those planets spinning in the same solar system. No wonder DC and Warner Brothers happily hand-over creative control for each of their independent universes. When asked about Supergirl, Nina Tassler, President of CBS Entertainment, said “we’ve been given license and latitude to make some changes.” In other words, forget continuity, our Supergirl flies solo. That might sound less impressive—hell, it is less impressive—but orbiting inside the Marvel Cinematic Universe carries its own penalties.

Witness director Edgar Wright. The hilariously idiosyncratic British film-maker approached Marvel about Ant-Man back in 2004. The then-fledgling studio was delighted. But when production finally rolled around a decade later, the Marvel blockbuster mill wasn’t so keen on Wright’s personal take on a potential franchise. Avengers director Joss Whedon adored the script, but Marvel scrapped it, handed the rewrite pen to Paul Rudd, and subbed out Wright for the lesser known but far more malleable Peyton Reed. Granted, Reed’s miniature battle scene shot on a Thomas the Tank Engine train track was genius, but the rest of the film was by-the-Marvel-numbers.

There’s at least one potential reason for that all-controlling gravity. At the center of the Marvel Cinematic Universe spins a supermassive black hole named Disney. It also owns ABC, home of Carter and S.H.I.E.L.D. It was also the TV home for Superman in the 50s, Batman in the 60s, and—for a season at least—Wonder Woman in the 70s. But the Mickey Mouse subsidiary isn’t interested in promoting Warner Brothers property anymore.

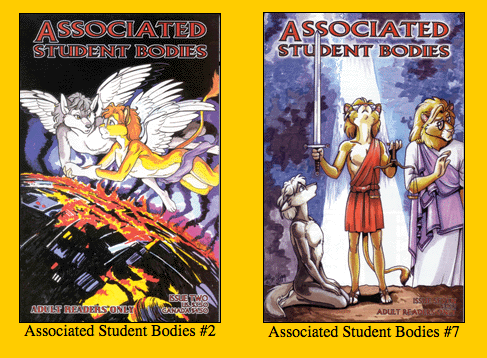

The megalomaniacal one-puzzle policy has even taken root in Marvel Entertainment’s root company, Marvel Comics. Its continuity used to include thousands of free-wheeling universes. On Earth-1610, Spider-Man is black and Hispanic; on Earth-2149, superheroes are zombies; on Earth-8311, Peter Parker is a pig named Peter Porker. There was even an Earth-616, where we all read Marvel Comics, and Earth-199999, home of the Evans, Downey Jr., and Hemsworth Avengers, who apparently are completely unaware that Marvel Studios is watching and recording them.

That all changed last summer. With its mini-series Secret Wars, Marvel Comics destroyed its fifty-year-old universe, and rebooted its most beloved characters into a single, one-size-fits-all reality (All-New All-Different Marvel!), in which its writers and artists must toil in perfect, lock-step synchronization.

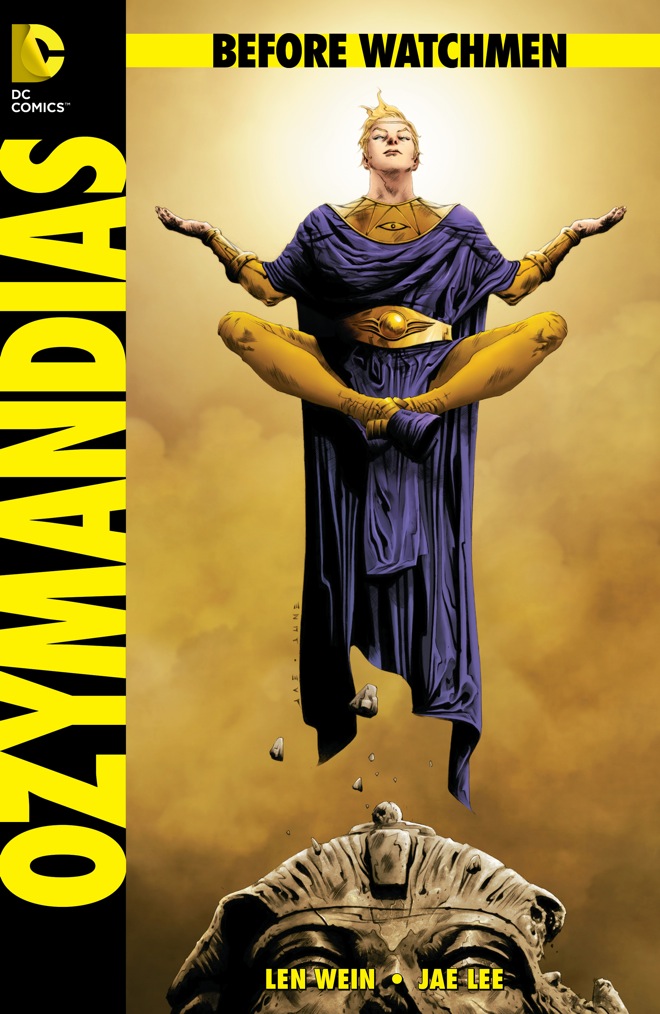

Meanwhile, DC is following Supergirl in the opposite direction. After their own recent, reality-transforming maxi-series Convergence, every character, storyline, and alternate world that’s ever appeared in any DC comic book is officially back on the playing field. Apparently the writers were envious of their TV and screenplay counterparts and wanted the same unfettered free-for-all. And now they got it.

So when you tune in to Supergirl Monday nights, enjoy the metaphysical implications of your viewing choice. That’s a whole new world blinking on your screen.