Adrian Tomine gives good interview. He’s thoughtful and smart, which are two different things, and self-deprecating in a way that isn’t designed to mask false modesty. He’s doing a lot of press right now, and in each conversation he offers something new. When I read his Q&As, I’m always struck by how low-key and likeable and honest he seems. Maybe it’s me and maybe it’s comics (and definitely it’s the format of Giving an Interview, which makes it near impossible to not sound like a self-serious asshole), but cartoonists rarely strike me in this way. If I were to overhear any given interview (including the ones I’ve conducted) as a conversation in a bar, I’d probably think those people sound like dicks.

Killing and Dying was my first time reading Tomine, and I had high expectations. Part of that is his likeability and part is his legend as indie comics’ most sensitive son. For every man in Tomine’s audience who finds the phrase “graphic novel” problematic (lol), there’s a sap like me who thinks it’s adorable that he was drawing love comics at age 15. An unhappy teenager who has grown into a vaguely anxious and uncomfortable adult—this is a figure who speaks to me and my struggle. Many of those art comics guys in the 40+ crowd—Chris Ware, Seth, Chester Brown—are eccentric and cold sort of alien beings, from my vantage. Tomine is more relatable somehow. I can see myself in him.

But, as it turns out, I do not see myself in his stories. In fact, I don’t see anything resembling a real woman in his most recent work. The world of Killing and Dying is filled only with men and the shells of the women who orbit them. Each of these women is characterized, if at all, by the degree of ambivalence with which she loves some sad fucked-up failure of a dude.

The first story, “A Brief History of the Art Form Known as ‘Hortisculpture,’” is an allegory about comics in which a dutiful wife and loving daughter try to support the bumbling man of their house, an artist. His journey is in coming to terms with his failure. Along the way, he makes things and destroys things. We know about his job and his hobby and how those things sustain and haunt him in turns. His wife and daughter, in sharp contrast, are not autonomous beings in the world of this comic. Their inner lives, their conversations, and their actions all center on the male protagonist. They support him, or worry about him, or feel embarrassed by him. They exist only in proximity to his dim sun.

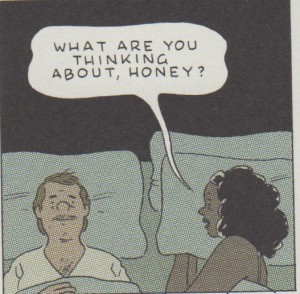

“What are you thinking about, honey? It’s important that you tell me because I don’t have any of my own stuff.”

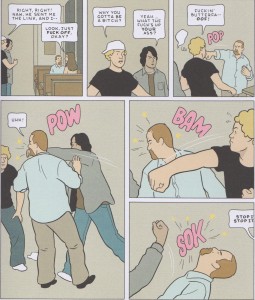

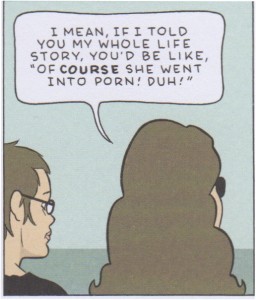

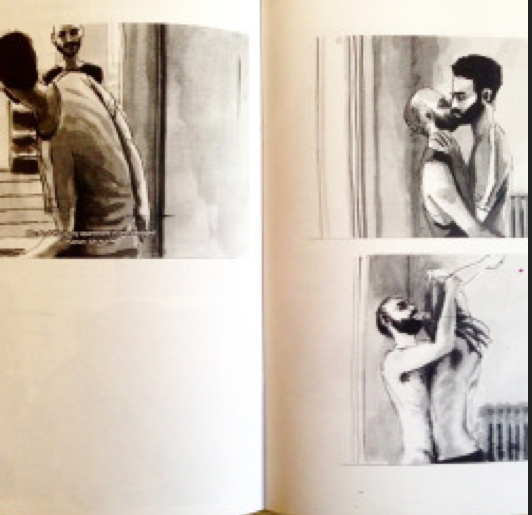

Similarly, “Go Owls” is the story of a pathetic man—Barry, a drug dealer—and his nameless female companion. Barry is a volatile person who is abusive and tender in turns. Tomine gives him both a backstory and a future. Barry even has an existence (such as it is) outside of the presence of his girlfriend, playing guitar and selling marijuana to soccer moms. Jane Doe, on the other hand, never appears on a page without Barry. Her long bouts of passivity are only punctuated by displays of one-upmanship when Barry says something dumb. (Even her cleverness exists only in analogy.) Otherwise the full extent of her characterization is a substance abuse problem and a sister she mentions in passing. Tomine’s subtle, expressive drawing clearly broadcasts her inner life, which seems to consist wholly of her contempt for Barry (unless you count her contempt for herself, which I don’t, since there is no “herself.”).

“Listen, babe. We don’t need your story, babe. You’re a babe, babe. And that’s your thing.”

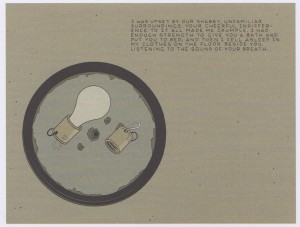

“Translated, from the Japanese,” the shortest and strongest story by a mile, is a sort of letter from a ghost to her son. From her innermost feelings to her outward actions, every detail this mother reports traces back to one of three guys in the story—her son, her estranged husband, or a college professor she happens to sit next to on a plane. You can pin all her thoughts and feelings on those three dudes. The only thing that gives the piece any depth is the suggestion that her story is a relic from a past from which she has since moved on. The emotional timbre of the story is that of a journal entry—and yet it’s addressed to the narrator’s son. Why?

“You fell asleep, and then so did I. It’s almost as though when you close your eyes, I simply cease to exist.”

“Killing and Dying,” the central story, also involves an absent woman. Other reviewers seem to think the story is about a teenage girl, but it’s not. It’s about the struggle of her tortured father. My god, this man is such a cliché.

Everyone knows dads don’t cook.

And so is his wife.

Moms just believe in you so hard. That’s literally all they do (in this story).

This man’s ~j o u r n e y~ is about learning to let his daughter Jesse make her own mistakes. Though Jesse has more grace and maturity than her father, she doesn’t develop over the course of the story in a meaningful way. And the wife, well, she doesn’t have much of a journey either. I don’t want to spoil anything, but let’s just say that on top of being a cliché, she’s also a sort of gimmick/technical device.

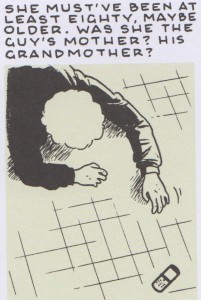

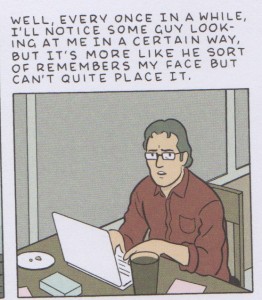

I don’t have much to say about the last story, “Intruders,” which is about a loner. But it’s telling that even its female “extras” are conceptualized in terms of the dudes to whom they belong.

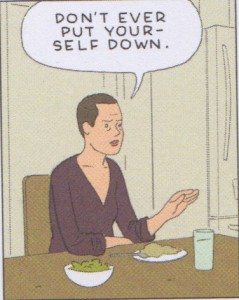

It’s not that the artist hates women. There’s no doubt that, in the Tomine universe, women are superior to men. The ladies of Killing and Dying are, for the most part, hotter, smarter, more patient, more successful, less self-absorbed, less ridiculous, and better adjusted than their male counterparts. Even when they’re flawed (like the nameless woman in “Go Owls,” or Jesse, the teenage comedienne), they’re sympathetic because of the unpleasant, limited man that it is their lot in life to endure.

I haven’t read Tomine’s other work (and I’m not sure I will), but I’ll wager his whole thing is idealizing women. I think about his iconic New Yorker cover, which takes one of the most solitary acts in all of womanhood—reading on public transportation—and turns it into a sort of love story. Or his similar, if lesser known, cover, which fetishizes a teenage girl reading Catcher in the Rye. Tomine’s gaze is focused on their books, not their boobs, but it still represents the point of view of someone who imagines the stares a woman receives to be little romances that unfold throughout her day. I guess from his point of view, it probably feels that way. Wistful. Idyllic. Not creepy.

When Tomine does touch on the subject of harassment, as he does in his story about a nameless college student who looks just like an Internet porn star (“Amber Sweet”), its effects are visited most vividly upon—wait for it—a man.

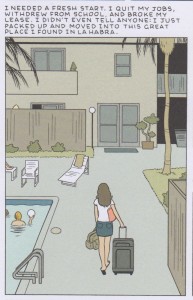

Unable to find a guy in college who will date her, Jane Doe quits her life and moves somewhere new.

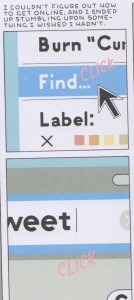

This story is broad to the point of absurdity. Perhaps to some extent that’s on purpose. Maybe Jane Doe is in fact Amber Sweet and that’s why her life story—a lie she’s telling a new love interest—itself sounds like a half-baked porn plot. Certainly she’s an unreliable narrator, as we see in a panel where her description of “stumbling upon something” doesn’t match the deliberate search we see her carry out in the panels.

But riddle me this: How come Amber sees harassment as a choice that she made for herself, rather than choices made by the men who harass her?

Why is Amber’s backstory a tired cliché?

And, above all, how is it that every single man in the United States of America seems to watch the exact same Internet porn?

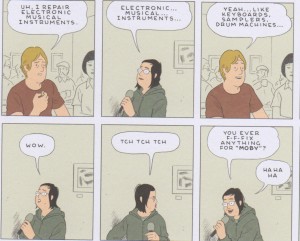

These are the kind of problems you run into when your character is a tool in your parable about fraught identity instead of a fully imagined person. And the same lack of attention to detail can be seen across Tomine’s female characters, who never quite ring true. Witness Jesse, a teenager whose top-of-mind pop culture references include Moby.

MOBY. I just can’t even.

Despite these missteps, Tomine’s talent is plain. There are quiet moments of real insight, like when he writes about how your neighbors on a long flight transform back into strangers after you deplane. He has a natural ear for dialogue. His facility with his pen across multiple styles (which he employs to great effect throughout the collection) really can’t be overstated. And his palette is flawless, demonstrating a masterful use of color that surpasses even Ware’s.

Still, even if you adjust for this industry’s tendency to make overblown declarations about the significance of any given project, Killing and Dying has been heaped with unearned praise. The most reserved review I’ve seen named Tomine “one of the most significant artists working in a young, fluid, thrilling genre.” The Globe and Mail praised his “mastery as a writer” and “peerless” cartooning skills. “A deft, deadpan masterpiece,” raved Publisher’s Weekly. The Kirkus Review straight up referred to him as a wizard.

The truth is that Killing and Dying is not the work of a wizard or a genius or even someone at the top of his game. Adrian Tomine is very talented, yes—but he’s also a writer with bald limitations. I don’t want or need to see myself in every comic ever written, nor do I think that every story requires a round female character. But an entire collection of stories in which women are props defined by their feelings for broken men? That is pathologically bad writing.

Whether it’s autobio or ciphers in fiction, art comics are packed with male protagonists obsessed with their own loserdom. I think too often they hate themselves for the wrong reasons. It bothers me how often work that’s praised for its “unflinching honesty” is drawn by men who are, to my eye, hopelessly blind.