This first appeared on Splice Today.

______

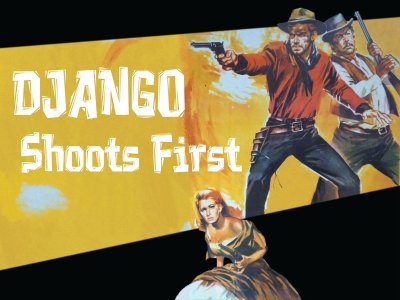

Dorado Films recently bundled together two late sixties spaghetti westerns — Django Shoots First! and Gatling Gun — as a budget twofer. Outside the classic Sergio Leone films, I’m not that familiar with the spaghetti western genre, so I was interested to check it out. And it was indeed educational. Here’s some things I learned about men, women, and guns.

1. Men sweat. Women take bubble baths. — As you’d expect, men are dirty and stinky like men should be. In fact, Robert Woods, who plays hero Chris Tanner in Gatling Gun, has carefully applied sweat to the middle of the back of all his shirts to show that it is hot and that he sweats, though because he is a hero he does it in a predictable and orderly fashion.

A woman, though, does not sweat. Not even when her dad has just been shot dead in front of her and she’s tied up and forced to ride across the desert in long-sleeves and bustles. Her make-up doesn’t even run.

Therefore, somewhat counter-intuitively, women need to take baths all the time. Bubble baths are ideal because all those bubbles can hide that dashing stranger from the sheriff so the two of you can betray your husband. Alternately, the bubbles can help hide your naughty bits when the sweaty evil minions drown you in the tub.

2. Heroes don’t get shot. Women can’t shoot. — It’s not quite true to say that heroes don’t get shot. They do of course get the occasional flesh wound just to show they can take it. Django (Glenn Saxson) gets tagged a couple of times in Django Shoots First!, and in Gatling Gun Chris Tanner gets a really nasty wound in his hand and has to dig the bullet out because he’s just that tough. Still, in general, it’s kind of amazing how utterly (ahem) impotent guns are against these guys. Tanner even dodges a fusillade from a Gatling gun. That’s some poor shooting there, bad guys.

Women on the other hand don’t even get the privilege of missing the heroes. In Django, the scheming bitch, Jessica Cluster (Evelyn Stewart), steals her sweetie’s gun as she kisses him, and then she tells him he’s a weak, sentimental fool and she hates him, ha ha. He looks suitably castrated, she pulls the trigger…and there’s no ammo. He removed it because he’s smarter than her and only guys know which end of that thing is up anyway. Then he sets her up so another ex-lover kills her. How’s that for castration, bitch?

The same thing (more or less) happens in Gatling Gun…and even to the same actress! This time Evelyn Stewart is Belle Boyd. She keeps a small pistol under her pillow, and after Tanner kills everyone she knows, she (being justifiably upset) prepares to shoot him with said pistol. But! He took the opportunity to take all her ammo while he was having sex with her the previous afternoon — fucking her while fucking her, as it were. “When you sleep with a pistol under your pillow,” he tells her sententiously, “you should be careful who you choose as your bedmate.” Don’t cross dicks with me, sweetie.

You’d think she’d take that amiss, but instead at the end of the film she rides off into the sunset with him. Maybe because humiliation is sexy? Or because he was just that good in bed? Or, more probably, because the two other women in the film got killed, and the hero has to ride off into the sunset with somebody.

3. Misogyny will wipe away all your sins. Class prejudice and race prejudice are bad, and the best way to show they are bad is by associating them with women, because who trusts a women?

In Django, the misogyny-for-a-greater-good is relatively subtle, and even accomplished with a touch of humor. Django’s a down-at-the-heels drifter deadbeat who challenges the big-deal, well-dressed banker Mr. Cluster (Nando Gazzio) for dominance in the town. Jessica, the banker’s wife, is both a money-grubbing, castrating bitch (constantly demeaning her husband) and a snob (she sneers at waitress Lucy (Erika Blanc), provoking a catfight.) Jessica’s greed and desire for luxury map easily onto her upper-class evilness.

The duplicitous effeminacy of the swells is further emphasized at the film’s conclusion, when Django, now wealthy and married to Lucy, swaggers foppishly around the bank he owns. Suddenly, a rough and tumble outsider enters and threatens to do to Django what he did to Cluster. By marrying Lucy and settling down, Django’s been feminized — and now he’s the enemy!

Gatling Gun doesn’t bother with the tongue-in-cheek cutesiness. The evil half-breed Tapas (John Ireland) is in love/lust with Martha Simpson (Claudie Lange). He gives her money, but she still rejects him because she’s an unrepentant racist. Tanner sleeps with her himself to get information out of her. She spills the goods on Tapas…at which point Tanner turns on her, sneering at her for her unfaithfulness and her prejudice. In a final fuck-you, he tells her he himself is a quarter Cherokee. Shortly thereafter she gets killed as punishment for her sins, which include racism and having the temerity to bad-mouth one man to another man even if they hate each other. Whatever color, whatever creed, guys gotta stick together.

4. Look not to exploitation fare for enlightened gender politics. I did kind of know that one already, I’ll admit. Though, to be fair, I don’t know that the treatment of women is really much worse than what you find in most present-day action flicks. The spaghetti westerns are just — for better and/or worse — more honest about it.