Every so often Marvel attempts to explain some of the weirder aspects of the fictional universe described in their comics by invoking some more-or-less obscure bit of science, technology, engineering, or mathematics. I am concerned with the mathematics today, and in particular the way that the mathematics of the transfinite has been used (abused?) to explain the relative power status of various ‘cosmic’ beings (e.g. how can one omnipotent being be more powerful than another?)

Every so often Marvel attempts to explain some of the weirder aspects of the fictional universe described in their comics by invoking some more-or-less obscure bit of science, technology, engineering, or mathematics. I am concerned with the mathematics today, and in particular the way that the mathematics of the transfinite has been used (abused?) to explain the relative power status of various ‘cosmic’ beings (e.g. how can one omnipotent being be more powerful than another?)

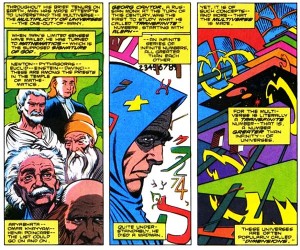

One such incident occurs in Doctor Strange: Sorcerer Supreme #21, where it is implied that the Marvel multiverse is made up of the transfinite numbers. Transfinite cardinal numbers – presumably the authors don’t have ordinals in mind – are the numbers that measure the size of infinite sets (the finite cardinals are just the numbers that measure the size of finite sets – that is, 0, 1, 2, and so on). Since there is an infinite series of larger and larger infinite sets, there is an infinite sequence of transfinite cardinal numbers. Georg Cantor, who was the first mathematician to study transfinite numbers, himself makes an appearance on this page, although for some reason he is transformed from a German mathematics professor to a Russian monk (I doubt Cantor ever wore a cool hood like the one in the art – Cantor did in fact go mad, however). But the page makes a deeper mistake: a tranfinite number is not a (cardinal) number greater than infinity, but rather a (cardinal) number greater than any finite cardinal number (thinking about the etymology of the word should have made this clear: “transfinite” is “beyond the finite”, not “beyond the infinite” – presumably they meant something like Cantor’s notion of the absolute infinite, which is beyond all the transfinite numbers, but whose existence is highly controversial amongst mathematicians and philosophers who work in this area).

Things get a good bit more confusing in other, later comics, however. In the page reproduced on the right, Kubik is explaining the nature of infinitely powerful cosmic beings to the newly formed Kosmos (I think it’s from Fantastic Four somewhere – please school me on the exact reference in the comments!) First off, Marvel seems to equate omnipotence with being infinitely powerful (already problematic). But then, since on this reading of “omniscient” there are lots of omniscient beings in the Marvel multiverse, and some of these are clearly more powerful than others, an explanation of this discrepancy is required. Cleverly, Cantor’s hierarchy of transfinite numbers is wheeled in to do the job.

So far, so good. But the problem is this: they get the math wrong – badly. Here is the relevant bit of the conversation between Kubik and Kosmos:

Kubik: Consider then, the set called whole numbers ~ 1, 2, 3, 4, and so on. Is it not infinite?

Kosmos: Obviously.

Kubik: Then consider the set called the even numbers ~ 2, 4, 6, 8, and so on – how long is it?

Kosmos: Why, infinite, of course.

Kubik: Half of infinity is still infinity. And the same would be true of the set of odd numbers?

Kosmos: Of course.

Kubuk: Both sets are infinite, and yet the set of whole numbers contains both subsets, and is therefore twice as large as either subset alone.

Kosmos: …? … !

Kubik: Thus are demonstrated two levels of infinity. There are, of course, an infinite number more.

[Admission: I like to interpret the fourth panel – the close-up of a shocked Kosmos where she utters “…? ….!” – as depicting Kosmos’ dismay at what a crappy mathematician Kubik is, especially for an infinitely powerful cosmic being. But I suspect that is not the reading the creators intended – see below!]

Basically, the infinitely powerful Kubik has achieved a cutting edge level of mathematical expertise – or would have, were it about 1600 AD. The confusion here is pretty much what has come to be called Galileo’s paradox: How can the collection of even numbers be both half the size of the collection of whole numbers, since we obtain the evens by taking every other whole number, and also the same size, since we can match up each even number to exactly one whole number (and vice versa) as follows:

1 <–> 2

2 <–> 4

3 <–> 6

4 <–> 8

5 <–> 10

and so on.

Roughly three hundred years later, Cantor cleared all this up. Basically, his idea was that two sets are the same size if and only if the elements in the sets can be matched up one-one like the wholes and evens are above, and are different sizes if they can’t. He also proved that for any set (including any infinite set), there is another set that is strictly speaking bigger than the first set. As a result of Cantor’s insights (along with those of other mathematicians including Dedekind, Zermelo, and others) set theory is one of the richest and most productive areas of modern mathematics. But here’s the kicker: the set of all whole numbers, and the set of even numbers, aren’t an example of this phenomenon: they are the same size, or, in more technical jargon, have the same (transfinite) cardinal number, since they can be mapped one-one to one another as shown above (self-serving plug: for a good, rigorous yet readable introduction to all this, see Chapter 4 of this excellent book!)

Now, the obvious explanation of all of this is that the writers at Marvel recalled hearing something about different sizes of infinity in a philosophy course at some point during their alcohol-soaked college years, but couldn’t remember the details (or misremembered them, etc.), and so they just made some shit up. Fine and dandy. But the really interesting question is this: How should we interpret passages such as the one above, where cosmic beings seem to be sincerely explaining the nature of the multiverse in terms of transfinite cardinal numbers, but where they get the mathematics horribly wrong?

Now, the obvious explanation of all of this is that the writers at Marvel recalled hearing something about different sizes of infinity in a philosophy course at some point during their alcohol-soaked college years, but couldn’t remember the details (or misremembered them, etc.), and so they just made some shit up. Fine and dandy. But the really interesting question is this: How should we interpret passages such as the one above, where cosmic beings seem to be sincerely explaining the nature of the multiverse in terms of transfinite cardinal numbers, but where they get the mathematics horribly wrong?

The first option is to interpret the incident as one where Kubik just makes a mistake. On this reading, everyone, including infinitely powerful cosmic beings, are fallible, and Kubik just didn’t pay enough attention in his “advanced mathematics of the infinite” course at Cosmic Beings College. But this seems a stretch. After all, setting the mathematics aside, it seems clear that we are meant to take this page to be a sincere and correct explanation of the nature of infinite powers within the Marvel universe (i.e. the creators intended us to interpret it that way and, barring ret-conning or other overt manipulation of the content, it seems that is enough to justify the claim that we ought to understand the page that way).

The second option is to interpret the incident as one where Kubik gets it exactly right. On this reading, the mathematics of the Marvel multiverse is just different than the mathematics that holds in our actual world. Of course, most philosophers and mathematicians think that mathematics is necessary – that is, that the truths of mathematics are the same in any way that the world could have possibly been (further, many think that even in ‘possible worlds’ where the laws of physics might be different, the laws of mathematics would remain the same!) In short, there is a way the world could have been where I was a mathematician and not a philosopher, but there is no way that the world could have been where there are more whole numbers than natural numbers. As a result, Marvel comics are describing a ‘reality’ that is not even possible in a basic, logical sense.

As a result, if we opt for the second reading, then we find ourselves in a conundrum: If Marvel’s comics, and the description of the multiverse contained in them, is a correct description of that multiverse, but is also (from the perspective of the real world) completely impossible – that is, the world couldn’t possibly have been that way – then it is not clear that, in some deep sense, we can understand these comics in the first place. The characters depicted in these comics live in a reality that is so different from our own that it is not clear what it might mean to say that we understand what living in such a world might be like. But of course we do seem to understand what living in such a world might be like, and presumably we think that we get more information about what it would be like every time we read a new Marvel comic. Hence, the conundrum.

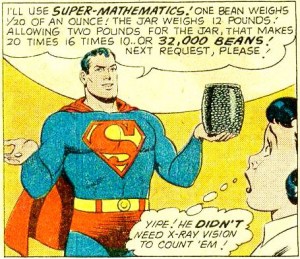

Of course, DC might have even bigger problems along these lines – see the Superman panel above.

Alright – discuss!