All images ©Edie Fake. Used by permission.

Gender is a relative phenomenon. To many red-blooded, sports-loving Americans, any serious interest in a quaint aesthetic medium like comics is likely to brand you as artsy, nerdy, and generally feminized. Similarly, many Wizard-readers and John Byrne devotees view indie comics fans as…artsy, nerdy, and generally feminized. And within the independent comics community itself, aficionados of the blood, scat, and sex of the old-style undergrounds tend to see the new, psychedelic, pastel, collaborative projects of Paper Rad as — you know the drill.

And yet, in many ways the Fort Thunder/Paper Rad axis is one of the more convincingly masculine endeavors in American comics history. Super-heroes, with their bulging muscles, high-camp exterior underwear, and soap-opera plots, are pretty darn gay, as I am not the first to point out. Similarly, the traditional underground’s guilty focus on male arousal and bodily functions reads as an adolescent (and therefore feminized) imitation of manliness, rather than as the real deal. In contrast, Fort Thunder’s intricate formal textures and its improvisatory swagger put it firmly in the bone-headed tradition of male-artist-as-incomprehensible-genius that stretches from James Joyce to Jackson Pollock to Bono and beyond. Forget the day-glo teddy bears (and the fact that some of the Fort clique are women) — Fort Thunder’s art is about the tiresomely agonistic psycho-drama of proving you’ve got it — and, in this context, the thing you’ve got is inevitably going to be gendered male.

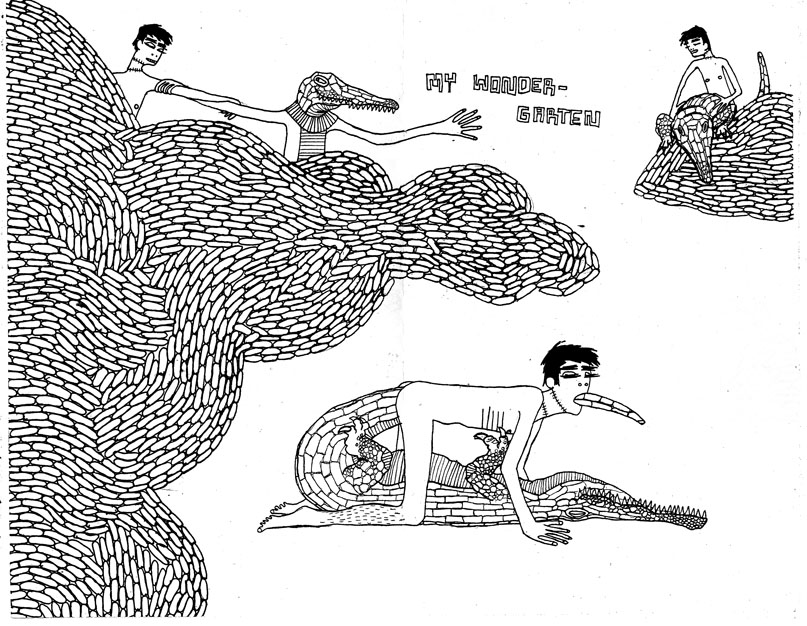

Which brings us to Edie Fake and his self-published mini-comic series Gaylord Phoenix. Fake isn’t exactly part of the Fort Thunder crowd — he’s a little too young, for one thing — but he did do some time in Providence, and his work has more than a touch of the Fort’s sensibility. The emphasis of his art is not on realism or narrative clarity, but rather on two-dimensional patterning. Foreground elements — characters, props, even text — are rendered in a simple, child-like manner, while the background designs and page layouts incorporate the sophisticated conventions of modernist abstraction and collage. But while the visual cues may be Paper Rad, much of the action in Fake’s comic is lifted right out of the ’60s underground; there’s lots of sex, lots of grotesque dismemberment, and a queasy tendency to link the two. So, on the surface, Gaylord Phoenix seems to have one foot in the male-gendered avant-garde and one in the male-gendered rape fantasies of the head shop.

Of course, “seems” is the operative word here — that, and possibly “Gaylord.” Fake is a female-to-male transsexual and his take on gender is, umm, queer. Though he uses multiple male idioms, they tend to undermine rather than reinforce each other. The abstraction, for example, distances the sex and violence; when someone’s penis looks like a macaroni tube (or a giant bundle of macaroni tubes), it’s difficult to be titillated by the ensuing action. Similarly, the narrative elements which link Gaylord Phoenix to comics history keep it from functioning as a truly virile avant-garde statement.

In fact, when you read it closely, Phoenix starts to look a lot less like any sort of male-gendered project and a lot more like that most stereotypically female of genres, fantasy romance. The plot centers on the title character, Gaylord Phoenix, who, against a backdrop of otherworldly landscapes, magical creatures, and ominous portents, seeks love and self-knowledge. Like many a romance heroine, Phoenix is possessed of buried powers and is, moreover, subject to fits of amnesia — thus exterior quest and interior journey are bound together by mystery, and the book is ultimately about the magic of becoming a woman.

Or a man. Or something. Gaylord Phoenix seems male, anyway (though his penis does go AWOL on a couple of occasions), and his lovers are either male also or else of no discernible gender. This doesn’t necessarily violate romance paradigms, of course, especially in the age of yaoi and its pretty bishonen boys. Yet, as a romance protagonist, Phoenix does have some serious drawbacks. The stars of romance, as every girl knows, are supposed to be glamorous, or cute, or both. Gaylord Phoenix is emphatically neither — with his giant nose, razor teeth, spindly naked body, and obtrusive body hair, he’s unlikely to be mistaken for Sailor Moon. And while a traditional romance protagonist may be dangerous in a brooding, gothic idiom, he/she still doesn’t generally turn into an evil doppelganger and dismember his/her sexual partner after coitus.

Gaylord Phoenix doesn’t quite jibe as a romance for the same reason it doesn’t quite jibe as anything else. Gender and genre share more than just a Latin root; they’re bound together, and if you violate the conventions of one, the conventions of the other start to unravel as well. The result in Gaylord Phoenix is that, while some individual moments are familiar enough, they never fit together in the way you’d expect. For example, at the beginning of issue 4, Phoenix is summoned through a magic ritual performed by a group of four rather grotesque wizards, all of whom share a single gigantic beard. Phoenix asks them to help him find his evil doppelganger “other.” The wizards tell him “the other lies within you”: a straight-forward, high-fantasy, Jungian Yoda interchange. Then, on the next page, and without missing a beat, the wizard-clump offers “to draw [the other] out” — and proceeds to perform oral sex on our hero.

Surreal shifts in genre and tone are a pomo default setting at this point, of course, from the smarmy ironic nudge-nudge of McSweeney’s to the exhilarating ironic bricolage of Japanese post-everything rockers the Boredoms. But that’s not where Gaylord Phoenix is coming from either. In the first place, Fake’s narrative doesn’t have the forced, performative feel of Borges — or of Paper Rad, for that matter. Nor is Gaylord Phoenix ironic. In fact, everything that happens in the story has an elegant, even heart-felt logic. Thus, in the scene with the wizards, it makes perfect sense for them to try to bring forth Phoenix’s “other” through fellatio — remember, the doppelganger manifests after Phoenix has sex. Moreover, throughout the book, and with pornographic inevitability, everyone Phoenix meets wants to fuck him. But though the wizard menage is telegraphed in some sense, it’s still basically asexual-wise-men porn. As such, it caught me completely off-guard, even on my second time through.

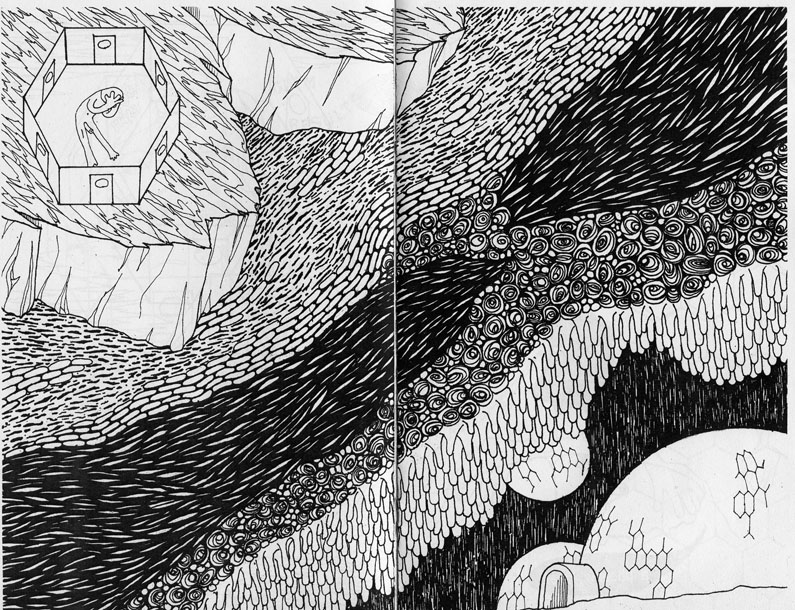

Fake’s use of narrative is deft and surprising. As in dreams, however, while the existence of the plot is important, the twists and turns are not exactly the point. Thus, the summary of issue 1 at the beginning of issue 2 is more than a simple recap. It’s a work of art in itself — a koan stenciled in uneven lines and written in a half-cracked patois (“the gaylord phoenix/born of crystal claw/killed his love on desrt [sic] sand &/ flees to pyramidal city/while his murder dies/ below the earthshell.”) In fact, throughout the series, the parts and the whole don’t so much compete as shimmer and change places. Instead of using traditional panel borders, Fake treats each page or two-page spread as an individual composition. In one image, Phoenix’s headless lover spouts gorgeous, simplified leaf shapes and giant, almost photo-realistic nuts and bolts from his neck stump and tubular penis. In another, a centered, black, ghost-like creature with fangs explodes in a twisting mass of severed tentacles and wounded swordfish from the mouth of a textured volcano; to the sides, forming a kind of background, are masses of intricately and identically patterned fish. In an image from the fourth book, which uses green as a spot color, Phoenix stands in a forest — five black-and-white tree trunks rise up to a mass of black and green geometric leaf shapes which form an impenetrable canopy; a black cloak floats in the air, spouting leaves, while above Phoenix’s head the stenciled text ominously reads, “You are under many spells.”

I could go on. And on. Every time you turn the page — especially in issues 2, 3, and 4 — you’re looking at a different, separately imagined work of art. Obviously, this doesn’t contribute to speed of reading. Instead, the narrative slows down, frozen, as you take in each image. The sequential movement of the book is vitiated; it doesn’t really read like a comic at all. Instead, it’s like pictures from a dream — or an art gallery. Indeed, in both his obsession with design and in his elegant mastery of the boundary between representation and abstraction, Fake seems like a Bauhaus artist who has wandered out of his proper era, a formalist mystic cast adrift in a sea of slapdash, toked-up mini-comics rebels.

Not that Fake is Paul Klee — or anybody else, for that matter. Gaylord Phoenix is that true rarity, an honest-to-God uncategorizable piece of art. At some moments, the strangeness is deliberately awkward and funny, as in a goofily suggestive scene where the black ghost/sea vapor creature hangs above a psychedelic whirlpool and inquires suggestively, “do you admire my vortex?” At other moments, though, the sense of alienation is haunting, or even oppressive. During a sex scene in issue #2, a resurrected, hypnotized man with visible stitches around his neck has sex with a variably humanoid crocodile. In one ecstatic drawing, the crocodile’s tail goes into the man’s anus and out his mouth. In another, the man is three men, one sitting astride the crocodile, one with the crocodile’s nose in his tube-like, oddly vaginal penis, and one with the crocodile’s tail going into his ass, the tip emerging from his cock. In the background, vaguely organic forms flow and pulse, each tiled with what looks like crocodile scales.

These sequences again suggest Fake’s connection with romance. This is a tradition in which identity, gender, and sex are both linked and fluid, leading to the compulsive body-morphing and androgyny in shoujo or the oceanic fusion with nature in D. H. Lawrence’s love stories. Usually in romance, though, there’s something to hold on to (genre tropes and drawing style in shoujo; the realism of Lawrence) which makes the mystical experience of desire seem, well, mystical. For Fake, though, there’s no anchor to which the self is attached before it comes under assault. In the first scene of the first book, Gaylord Phoenix (sans penis) is “exploring the secret grotto” (the unconscious? the womb?) when he is attacked by “crystal claw,” which enters him through his leg and brings his doppelganger (and his male genitalia) into being. There’s no moment when he is himself. On the contrary, his lack of identity — his bifurcation, his memory loss, his sexual ambiguity — is what defines him. Similarly, he and other characters move from landscape to landscape (cave, maze, sea, forest) with the unpredictable suddenness of Alice falling down the rabbit hole. But this isn’t Alice. Fantasy and reality, internal and external, aren’t even provisionally distinguishable. The self and the world are one constantly mutating whole. There is no waking up.

Fake’s disquieting perspective on gender sets Gaylord Phoenix apart even from other queer-positive comics, like Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home. Bechdel’s book is, like many gay narratives, obsessed with the dichotomy between truth and fiction, and with the importance of being faithful to one’s real self. The catch is that the structure, or “self”, of Bechdel’s by-the-numbers memoir is a cluster of clichéd literary tropes: as the old joke goes, the book urges you to be unique, just like everybody else. Gaylord Phoenix, on the other hand, is really and truly bizarre, in part because it seems to deny the possibility, or even the existence, of a separate, distinct inner core.

Fake’s vision is a little closer to that of Lost Girls — in which Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie imagine a sunlit tomorrow where bodies and pleasures flow deliriously and without restriction. The difference it that, in Gaylord Phoenix, the merging of id, ego and reality is not a hope for the future, but the world as it is, and it’s not exactly a utopia. Who we are and what we want — our relationship to each is like our relationship to dreams, mutable, illusory, and tenuous. For Fake, “queer” isn’t a biological quirk, or a marketing niche, or even an oppressed minority. Instead, it’s an insight: a recognition that the boundaries of our desires, and therefore of our identities, are both arbitrary and fragile. That recognition is sometimes beautiful and sometimes frightening, but it is always there, and it is inescapable. “Help yourself,” Phoenix’s companion tells him at the end of issue four. It’s good advice, offered with love. But it also prompts the question, “Help who?”

A version of this essay was first published in The Comics Journal

********

Edie Fake’s website is here.

Edie Fake is participating in a symposium on the Gay Utopia which I’ve organized, and which should be online (hopefully) in late January or early February. Other participants include Dame Darcy, Johnny Ryan, Ariel Schrag, Dewayne Slightweight, Ursula K. Le Guin, Jennifer Baumgardner, Scott Treleaven, and more.