A couple weeks back I wrote a piece at the Atlantic where I talked about the way that big budget sci-fi isn’t interested in talking about the future. Instead, it seems to have blurred with super-hero films, in which progress is always already a current dream of power. Rather than a better society somewhere to come, we imagine an atemporal, ongoing empowerment. The future isn’t so much a possibility as a superpower itself; a technology which fundamentally changes nothing except our sense of our own awesomeness.

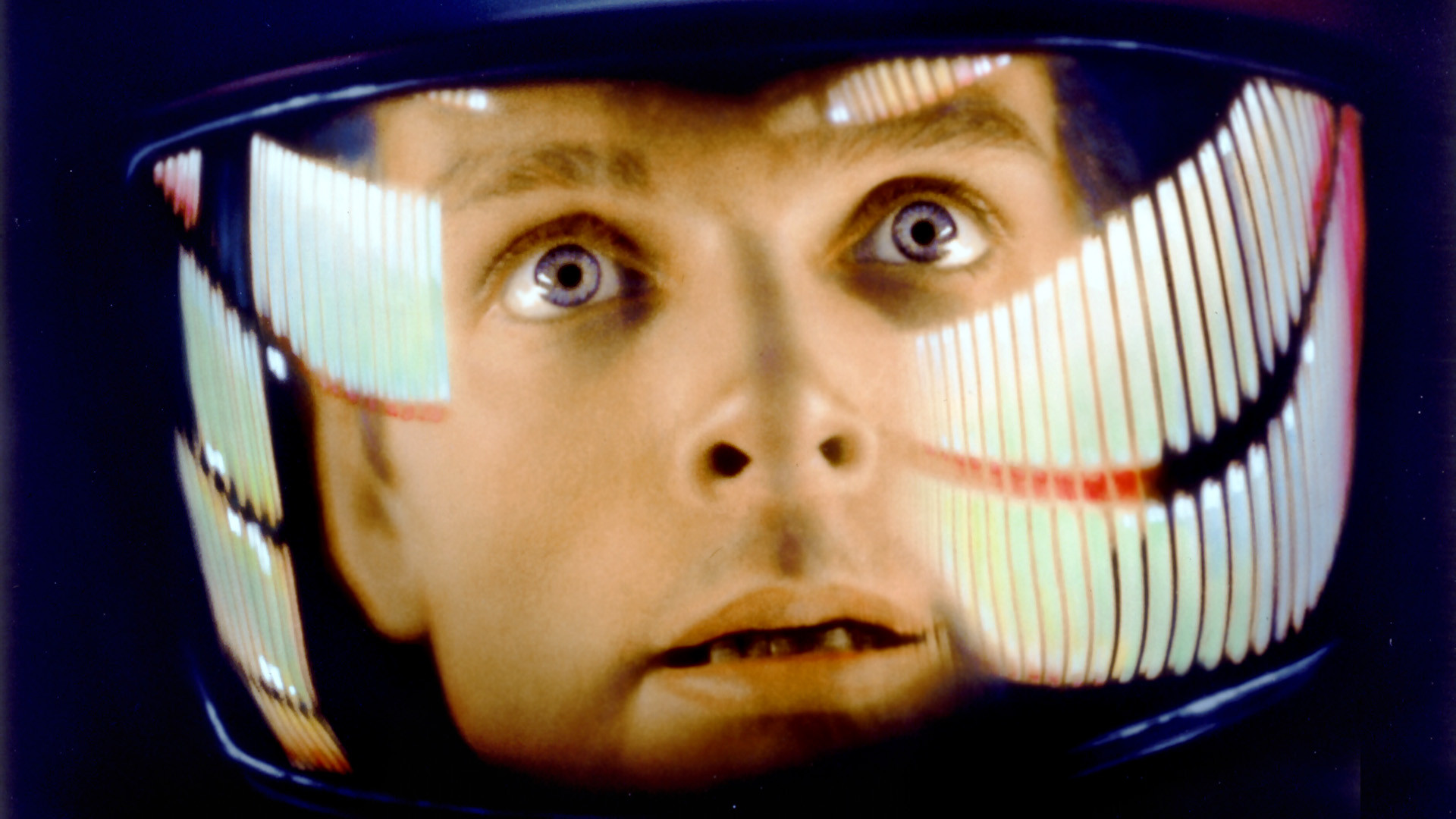

The best example of this probably isn’t actually current Hollywood, but Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. The novel covers vast swathes of time, not to rethink society, but to reinscribe that society from the dimmest past to the furthest reaches of time. Man-apes are led (like the name says) by men; the biggest, manliest man-apes are also the smartest man-apes, and the Cold War starts in the infinite past and never ends. Ursula K. Le Guin was writing about a world of single-gendered hermaphrodites, but for Clarke the women of the future are still mostly stewardesses, and the men are mostly bland bureaucrats; everyman David Bowman has the intense inner life of a stereotyped actuary. Space is a vivid, enormous landscape bestrode by tepid functionaries. The scene where Bowman finds a typical hotel room on the far side of the galaxy is meant to be trippy and unnerving, but it also, unintentionally, sums up the novel’s fundamental mundanity.

The energy of 2001 has nothing to do with reimagining the future or for that matter the present. Instead, it’s a superhero comic; the exciting bit, the wonder and the imagination, is all about turning that pallid Peter Parker into a superdude. And the superpower on offer, the transformative oomph, is literally progress, in the form of evolution. At the beginning of the novel, Moon-Walker the man-ape is pushed into being human by an alien obelisk; at the end of the novel, David Bowman is pushed into being more than human by yet another one of the same. The novel itself is essentially an origin story for man, man-ape and David Bowman. Aliens — some outside, wiser, smarter, something — reaches through the veil of space and time to shape past, present, and future into a superpowered unity of progress. Humanity is affected by, and is effectively itself, a New Age deity. There is no new fate or new possibility; just the current, satisfying knowledge of ongoing genetic potential. Nothing changes except apotheosis. Humankind will meet itself in the future, newborn and with space baby powers.

H.G. Wells in The Time Machine saw evolution as a blind, frightening master; time, in his story, does not care about humans, who it twists into dumb, hunted forms, and breaks meaninglessly upon eternity. Clarke, though, gives evolution a purpose; rather than Darwin’s blind watchmaker, you get a watchmaker with a cheery grin, ensuring that Mind prospers and Man, ultimately, triumphs over the millenia. There couldn’t be a much clearer demonstration that the purpose of the superhero is to defy time. Yes Superman never ages ‚ but more importantly Superman, on that rocketship, drags the future back to the present. The star baby plants tomorrow in today, by imagining perfection as timeless truth, unfolding now. We’re already superior, always have been, and always will be; mutants evolving before our own eyes. 2001 saw a future in which progress is neverending — and when progress is neverending, there can be no change.