A review of Tatsumi. Directed by Eric Khoo. In Japanese with English subtitles. Released 17 May 2011. Un Certain Regard 2011 Cannes Film Festival. [Comics reproduced in article read from right to left.]

Tatsumi (a cartoon adaptation of the manga of Yoshihiro Tatsumi) could be described as something of an anomaly — a project originating from Singapore which was made on the tiny island of Batam, Indonesia; a project no Japanese animation studio would have taken up if only because of its subject matter: slow, serious, immodest, and unsafe for children. The project’s unlikely instigator is one of Singapore’s most prominent directors, Eric Khoo, whose eighth feature this is.

Tatsumi represents Khoo’s first foray into animation. He dabbled in cartooning in his younger days, and those early works often reflect the urban angst and alienation found in many of his movies. As with Adrian Tomine (editor of the new Tatsumi translations published by Drawn & Quarterly), Khoo developed a passion for the gekiga of Tatsumi through the 1988 Catalan edition of Good-Bye and Other Stories. The motivation behind this project would appear to be simple. When asked about the impact of A Drifting Life (Tatsumi’s autobiographical manga) on him, Khoo had this to say:

“I could not stop thinking about it after reading it for three days and that’s when I decided I had to make a tribute film for Tatsumi.”

At 98 minutes, this is a bare bones version of A Drifting Life, charting in short and somewhat cumbersomely narrated sections his beginnings as a young artist, his meeting with Osamu Tezuka, his family travails, and the birth of gekiga. The film is remarkably faithful to the source text with Tatsumi’s comics panels providing the key animation frames and serving as a near rigid storyboard. Interspersed with the snippets of autobiography are adaptations of at least five works from the author’s 70s oeuvre, namely “Hell”, “Just a Man”, “Occupied”, “Beloved Monkey”, and “Good-bye”. These stories can be found in the collections Abandon the Old in Tokyo and Goody-bye, and are derived from the best period of Tatsumi’s work. There are also short sequences from Tatsumi’s pulp comic, Black Blizzard, highlighting and fetishizng its trashy roots by means of a faux four color process not dissimilar to the effect found on the cover of the Drawn & Quarterly edition of the same manga.

Despite Khoo’s personal affection for A Drifting Life, the fragments in the film derived from that novel are undoubtedly the weakest sections, serving largely as somewhat forgettable links to the five main manga adaptations found therein. Even cut down to its basics these segments will try the patience of viewers with any familiarity with the source material. The segment on Tatsumi’s meeting with Tezuka are the most coherent, the rest is inconsequential filler with little emotional drive. Worst of all is the clumsy and melodramatic episode depicting the destruction of the young Tatsumi’s art by his ailing brother.

The real aesthetic failure of Khoo’s film occurs in the differentiation between the autobiographical scenes and the fictional story elements. This blurring of lines may in fact be intentional — a reflection of the largely unvarying style Tatsumi uses for all his projects and also a subtle suggestion that Tatsumi’s violent themes emerged from his own torn psyche. The autobiographical sections are done in a kind of animation short hand (undoubtedly the product both of intention as well as budgetary constraints) and are shown in color for the most part. The fiction adaptations are done in raw black and white, and are more purposefully two dimensional to indicate the source material. Blurred elements intrude into the frame to mimic a camera lens’ shallow depth of field, and the figures are designed and drawn in a vigorous scrawl typical of Tatsumi’s pre-70s comics. They have none of the refinement of Tatsumi’s ink work found in stories such as “Sky Burial” and “Abandon the Old in Tokyo”. The light and breezy tone of A Drifting Life barely registers, and the segments covering it remain resolutely stiff and leaden, no different from the pre-70s strips they unwittingly mimic. The overall effect is not unlike a slightly evolved motion comic. The lack of aesthetic separation between the two narrative strands leads to a certain monotony; life and art inseparable yet flat in affect.

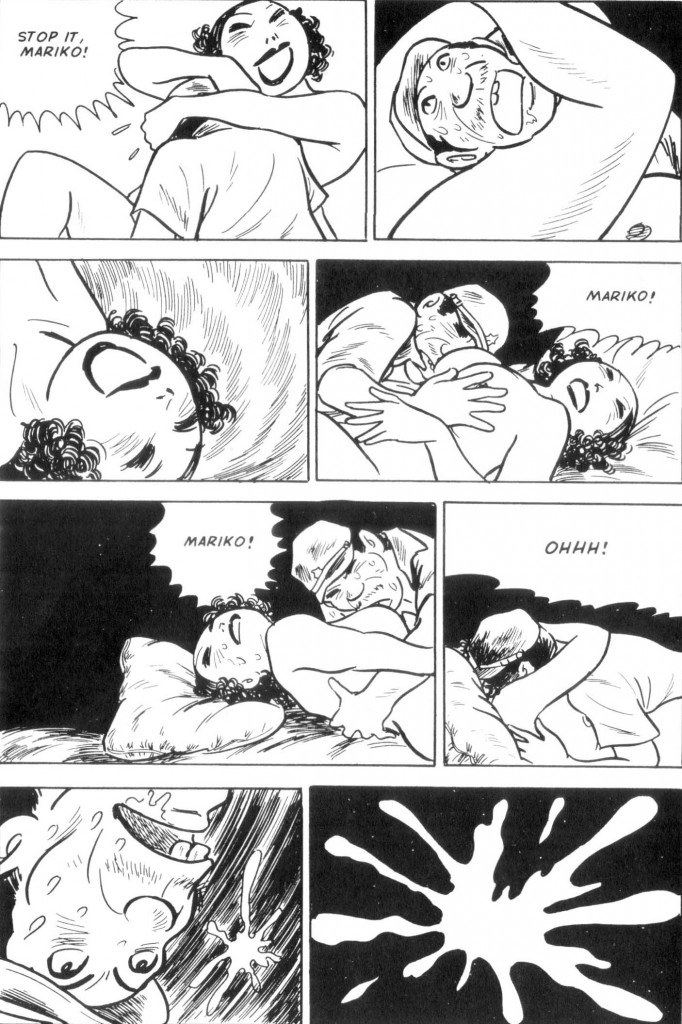

Sound is the one enhancing element in Khoo’s film. While the dubbing of the American soldier in “Good-bye” is calamitous (imagine John Wayne in a sex scene), the panting and gasping of coitus is wisely heightened to a pornographic hyper-reality which is totally in keeping with Tatsumi’s narrative ethos. Where Tatsumi shows us no more than one page of incestuous licentiousness, Khoo’s version is a loud, drawn out fucking.

It surpasses its source material because of its perverse animalism and utter lack of subtlety. The central hook of incest in “Good-bye” might have been sufficient in Tatsumi’s era but no longer. Producing an adaptation some 40 years later, Khoo periodic attempts to intensify the audience’s disgust and revulsion is largely a successful one.

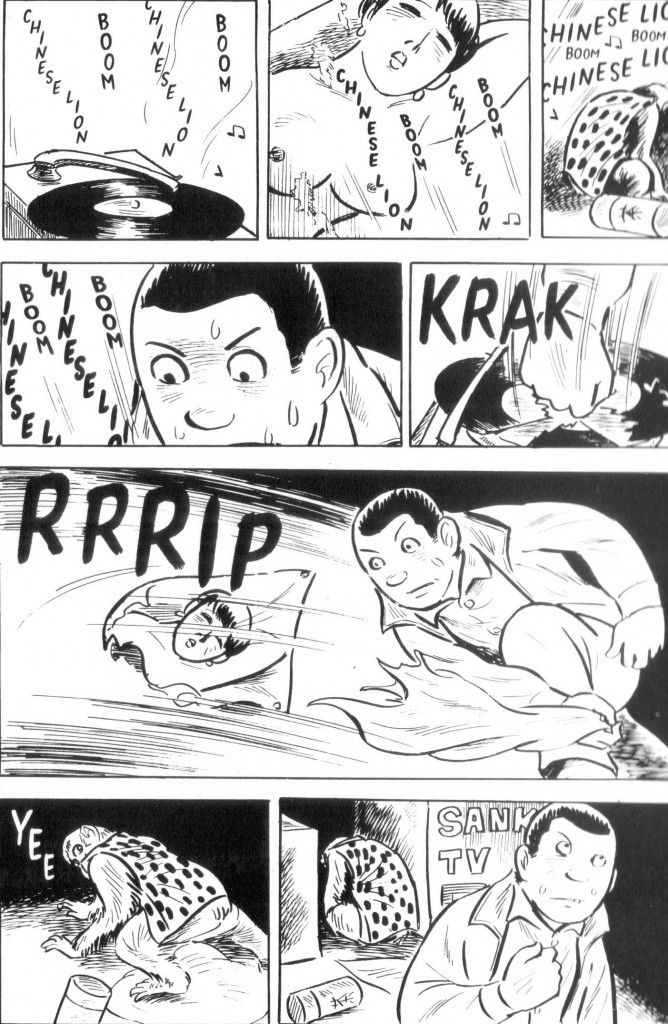

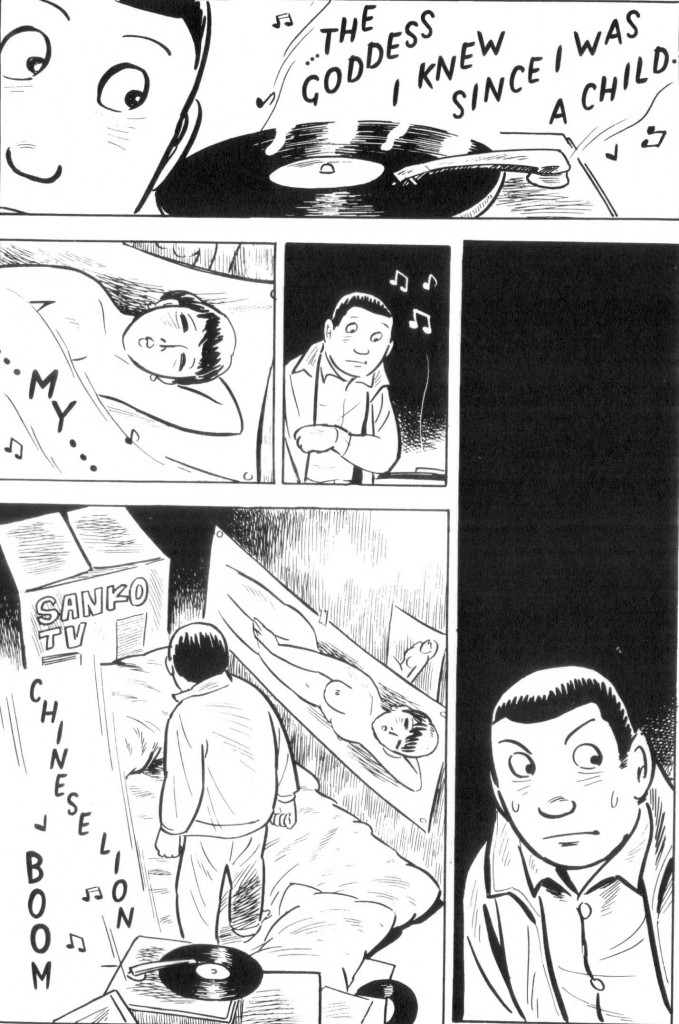

This isn’t the only time that the film adaptation highlights minor weaknesses in the original. The words streaming across the panels in an apartment scene in “Beloved Monkey” (see below) fall short of the more effective and annoying repetition of a stuck record player in Khoo’s movie.

__

__

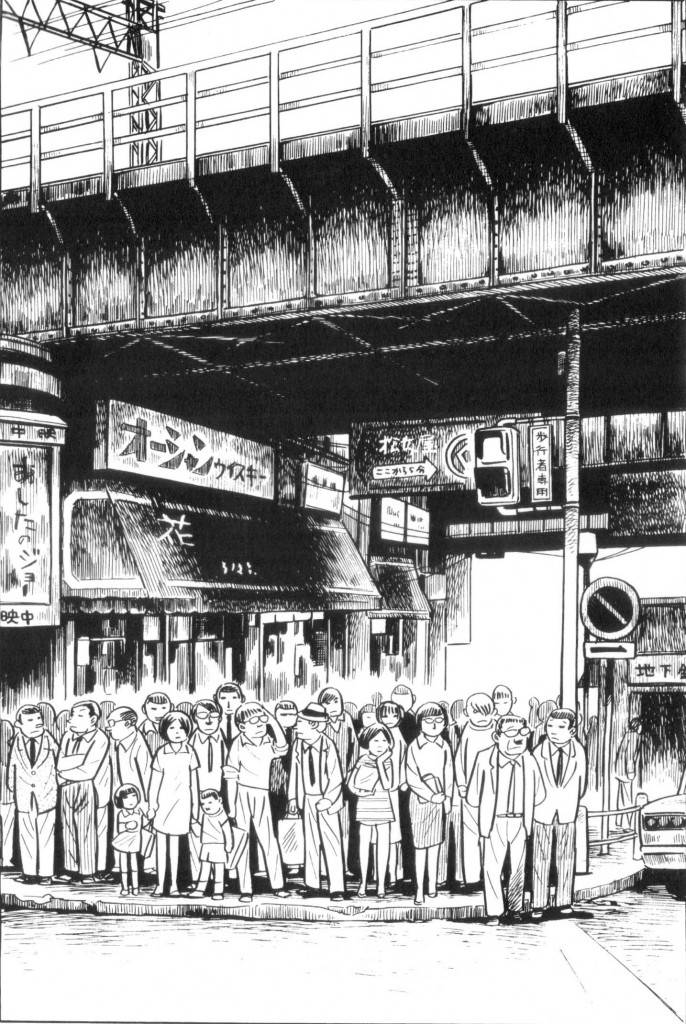

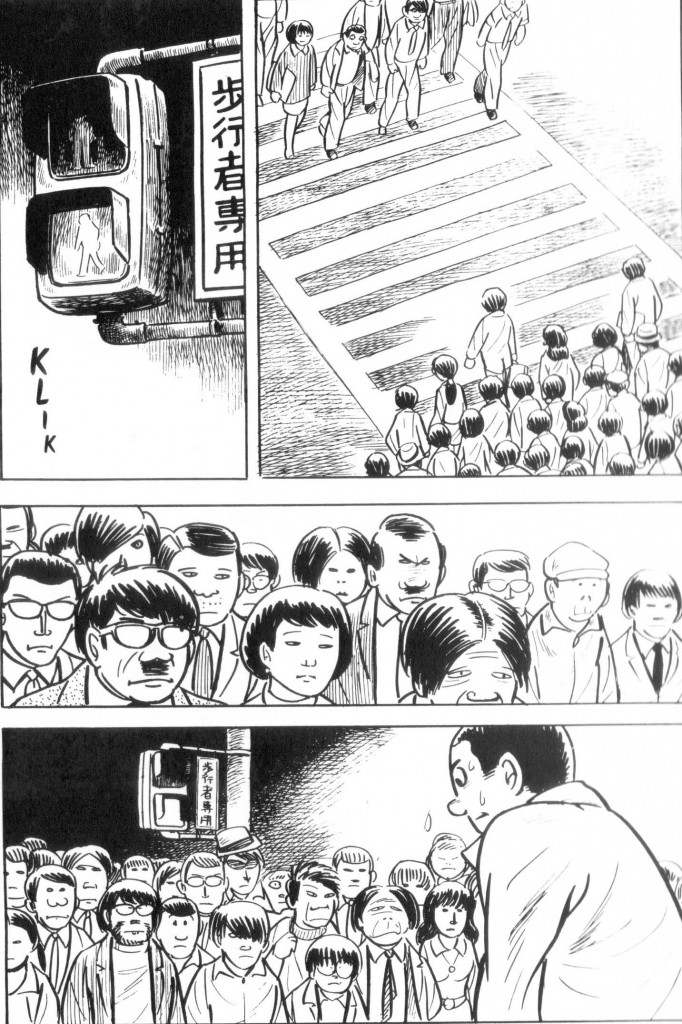

Similarly, the crowd in the final moments of the same story is considerably more threatening — closer, less accommodating, and more menacing — in the film version .

__

__

This may be a case of creative licence. The placidity of Tatsumi’s pedestrians suggest an over-reaction on the protagonist’s part, a festering agoraphobia. Khoo’s adaptation assures us of the validity of this fear. Whether these divergences simply reflect the relative strength and weaknesses of the respective mediums is a subject for another day.

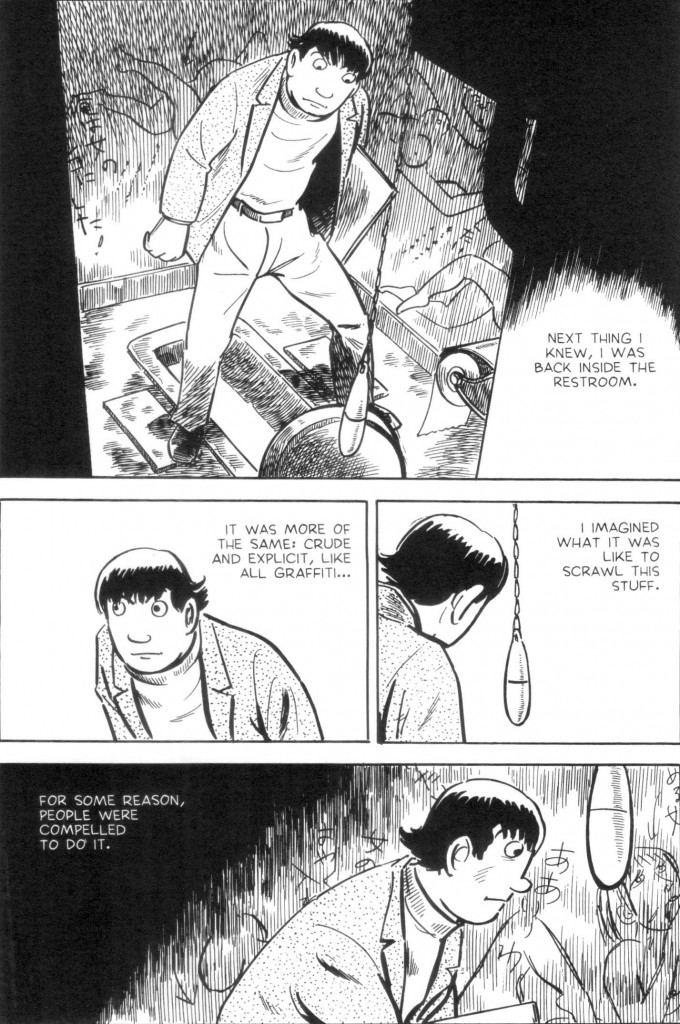

The decision to animate the pornographic graffiti in “Occupied” also yields good results; coarsening the almost asexual nature of Tatsumi’s depictions of female nuditity.

Yet Khoo oversteps the material near the end of his adaptation, introducing a cacophony of siren sounds where none exist in the manga; dampening the faint ambiguity of the manga’s conclusion. It is never clear from the manga whether the protagonist of “Occupied” is apprehended by the police. The film makes certain of this by adding the sound of handcuffs.

The subjective lengthening of the material which works so effectively for the scenes of lasciviousness has its occasional drawbacks. For instance, the opening scenes of a bombed out Hiroshima in “Hell” which are tediously drawn out and which quickly outstay their welcome. Every scene Khoo includes in his adaptation may be found in the original comic, and those 3 pages of ineffectual drawing are faithfully refashioned into a ham-fisted opening sequence only likely to impress the naive and uninitiated.

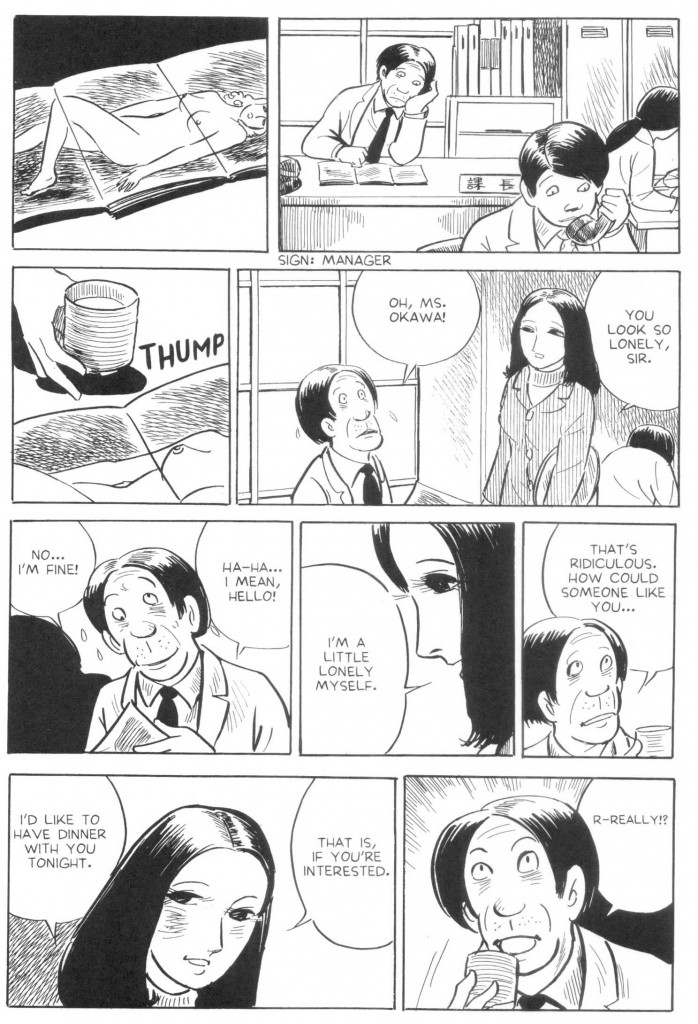

One might say that the weaknesses in Tatsumi’s stories are brought to vivid life in Khoo’s animation. The manner in which the secretary (Okawa) propositions her elderly boss towards the close of “Just A Man” drew giggles of disbelief from the audience on the night of my screening. In contrast, the panel work in Tatsumi’s manga simply slips past the reader in a matter of seconds causing little if any consternation.

More damaging than all of this is the frigid depiction of creativity; devoid of any sense of the artist’s passion except through the histrionics of the young Tatsumi (in the animation) and the personal claims of the narrator. The final act — that final moment of artistic revelation — where Tatsumi creates a drawing of his old neighborhood falls flat on its face due to the consummate mediocrity of the final product.

Still, the sheer faithfulness of Khoo’s adaptation makes it a perfect tool for publicity, particularly in reference to those who still see comics and animation as the province of children. As Khoo suggests in his interview at Indie Movies Online:

“Because I’m such a fanboy, I hope that people will see Tatsumi and realise “Hey, there’s something to these stories,” and maybe go and buy A Drifting Life, and read 800 pages-worth of his life.”

This is a perfect encapsulation of the film’s worth — a paean to a cartooning deity, a devoted act of promotion, and middling entertainment for the most discerning.

_______________________________________

Related Material

A substantive interview with Eric Khoo at Indie Movies Online

EK: What I told everyone is that, “We will use all his panels as the storyboard of the film.” We do not create any additional shots. Everything must be from the source. And what that meant was that some of the stories I had to edit. The hardest was his life. 800 pages! I had to condense it down to 35 minutes!