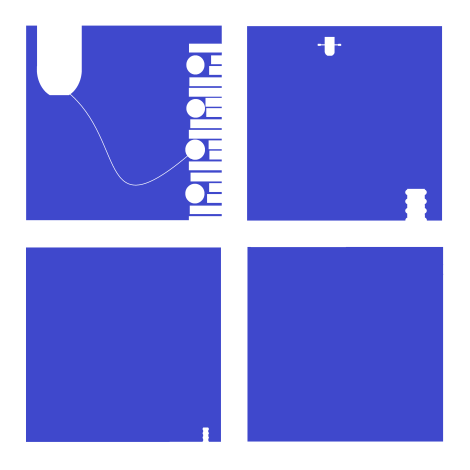

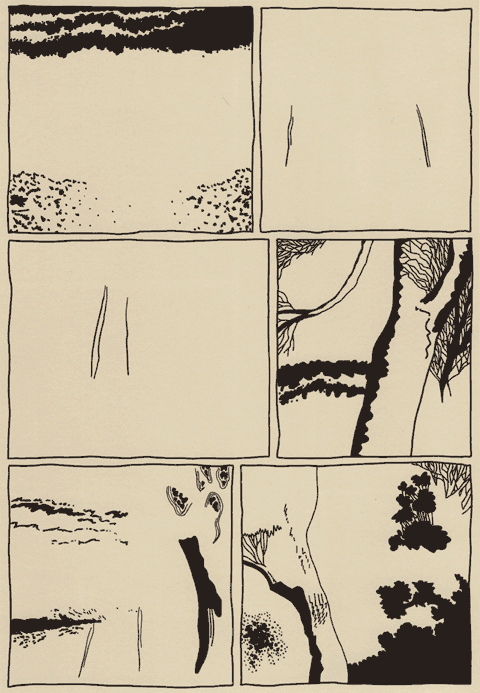

I’m going to say yes. And not just because the four-panel comic strip is titled “I rowed my father’s boat to sea.” The sequence tells a visual story whether those words are included or not. And the best way I know of discussing wordless storytelling is Neil Cohn’s visual grammar, which includes five types of narrative panels.

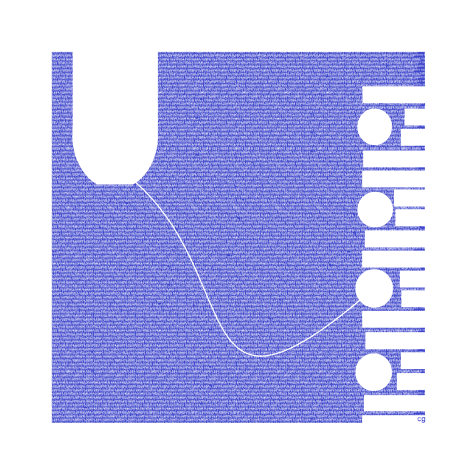

My first panel is an Establisher, which “sets up an interaction without acting upon it.” I’m not entirely clear what Cohn means (how is a set-up interaction not itself an interaction? if the panel content is the interaction, then how does the panel content also act upon the interaction?), but the panel does establish the two main visual elements: the boat and the dock. There’s also minimal tension between them. The panel by itself would not imply a story. If instead the rope were taut and the boat were pointed away from the dock, then there would be a plot.

My second panel is an Initial, which “initiates the tension of the narrative arc.” I’m not sure an awareness of the future arc is technically possible, but the panel has tension. The boat and the dock are now much further apart–presumably because someone in the boat is rowing it away. A lot of narrative information occurs between panels: the rower climbed into the boat, untethered it, and began rowing. All of that could be a visual sentence too, using the same panel one as an Orienter, which “provides subordinate information, such as a setting.” Instead, the rower is undrawn, and so the visual sentence is only between the boat and the dock. This second panel might instead be a Prolongation, which depicts a “medial state of extension.” If so, the Initial is implied as the sequence leaps to a later a moment in which the tension is already extended.

My third panel is either a Peak, the “height of narrative tension,” or it is the Release, which of course “releases the tension of the interaction.” Personally, I think the Peak, like the Initial, occurs in the gutter. The boat has already rowed out of sight, and so the tension is over. Alternatively, the boat and the dock are still interacting, because we project the existence of the still moving boat beyond the panel frame. Either way, the story is basically over.

My fourth panel is more clearly a Release, either of the third panel’s Peak or as a secondary Release which extends the third panel’s Release further. The blue is ambiguous. Has our perspective continued to move higher and so now the dock is so small it is effectively invisible? Regardless, the boat and now the dock are out of the image and so there is no tension.

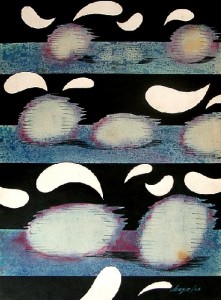

That’s all pretty straightforward. But notice that it all works on the assumption that pictures are pictorial. They picture something. While they are actually pixels on a screen, they are also representations of objects that are not pixels on a screen. So the story is about something that’s not actually present. The images are a little like words that way. Although, unlike words, pictures do to some extent resemble what they represent, they are also dissimilar to them. Even radically dissimilar. The “sea” is a blue square. The “boat” is an outline in negative space. The “dock” in panel two and three are recognizable only because they vaguely resemble the dock in panel one.

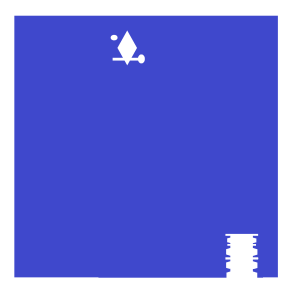

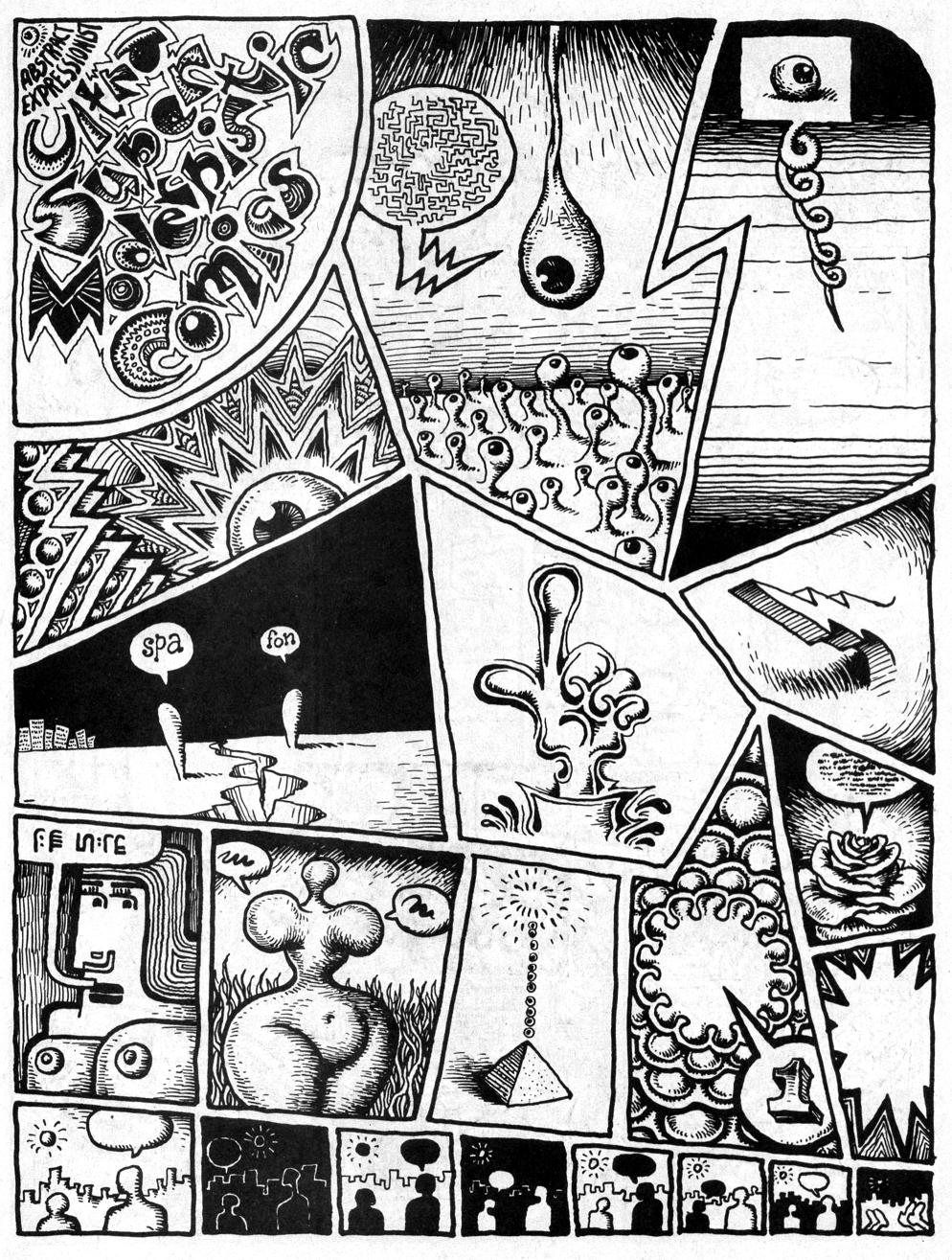

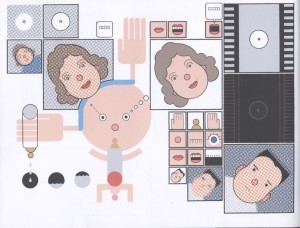

But what happens if there are no representational elements? If I replace the “boat,” the “dock,” and the “rope” with different visuals, do the four panels still tell a story?

The content of the revised panel one is now entirely abstract. Does Cohn’s Establisher panel type still apply? I want to say yes. The diamond in the upper left area and the random shapes along the right edge are still “set up,” and the overlapping circle between them suggests little or no compositional tension. The image is roughly balanced.

The second panel shrinks the first two elements, adding a few shapes to the diamond cluster, and doubling by mirroring and then simplifying and shrinking the second cluster of shapes. Are the two clusters interacting? Again, I want to say yes. The compositional tension is still low–but this was true in the representational version too. Although abstract, the tension is prolonged but waning.

The third panel is still either a Peak or Release–though now the diamond cluster can not be understood as having traveled out of frame. It simply does not appear. Also the former “dock” is not shrinking because our perspective is higher. There is no perspective. The shape is simply reduced in size.

The final panel again is all Release–no visual elements but the solid blue square and the white surrounding it. There is no tension. The image is perfectly balanced.

So the two versions of the four-panel sequence both follow the same visual grammar. Does that mean they tell the same “story”? Probably not. The first visual sentence is about a boat and a dock and someone rowing the boat out to sea. Things happen in time and space. The second visual sentence is about clusters of pixels. The only space is the space of the screen, and the only time is the time experienced by the viewer.

I’m not certain a “story” is possible without some kind of representation of time and spatial subject matter, but if it is, the second story is not the first story. They do, however, overlap. The abstract sequence and the representational sequence have the same arc. Is this inevitable? Since all representational images are also abstract marks (ink or pixels), do the two visual sentences always overlap?

Maybe. Unlike the above example, there would only be one set of images–whether analyzed abstractly or representationally. But that’s true of “I rowed my father’s boat to sea” too. The second just illustrates the innately abstract qualities of the first. Delete the second, and the first sequence is still open to both readings.

In both, blue dominates each successive panel until all white elements stop repeating. If blue is “water,” then the water dominates as the white of the “boat” and “dock” decrease in presence. In representational terms, this is because the boat rows out of frame as the viewer’s perspective grows higher until the dock is too small to see too. That’s not how I originally summarized the story though.

Using the grammar of the visuals as abstractions, blue has overwhelmed everything else. Not only has the boat moved far from the dock, the dock has shrunk away too. Since both decrease in size and then vanish, both are in visual tension with the water. I think Cohn would call the water “subordinate information, such as a setting,” but it actually serves as the sequence’s most dominant visual element. If this were a superhero comic, we might say the blue vanquishes the white. And since we begin the sequence identifying with the only human character, the implied rower of the boat, the blue is the villain. It destroys everything.

This reading occurs mostly at the abstract level. If we rely only on the representational qualities of the images, the water’s increase is primarily a side effect of the perspective and framing of the boat and dock. We are more prone to dismiss the blue as mere setting. Read abstractly, the blue is the story. The two visual sentences are not the same.

Does this mean that the meaning of any comic is incomplete if its content is read entirely or primarily in representational terms?