Adult Eyes

I spent my adolescence in Midlothian, Virginia, a suburb of Richmond, and graduated high school in 1992. At the time, I would have told you that my life was boring and lonely. Looking back now, with adult eyes, I think I likely misunderstood the situation. I was in fact, very busy, and on the whole I did things that I enjoyed. And while I was never what anyone would call popular, I had several friends — good friends, lasting friends — so much so that two decades later I am still close to some of them, though we live thousands of miles apart and see each other rarely. The problem was not that I was bored or lonely. The problem was that I was alienated.

I felt unnatural, out of place, lost, confused, disoriented, like a stranger who didn’t quite speak the language, like I was always, somehow, in the wrong before I even had a chance to act. Others treated me that way as well. They looked on me with suspicion, sometimes hatred, occasionally disgust. I felt oppressed, not only by the suffocating atmosphere of conformity, but by the very normalcy of the people around me.

And I wasn’t the only one. I was practically surrounded with other weirdos, other kids who felt trapped, and resentful, and sad. One of those other weirdos was Richard Kelly.

I didn’t know Kelly, and I don’t remember meeting him, seeing him, or hearing stories about him. But when I saw his film Donnie Darko, the sense of familiarity was unnerving and uncanny, like my internal experience was being projected onto the screen.1 It was only later that I learned why Donnie’s Middlesex so closely resembled my Midlothian; it was Kelly’s Midlothian as well.

I had a similar feeling, slightly diluted, watching Stephen Chbosky’s film, The Perks of Being a Wallflower.2 The resonances are less intimate and more generic — in Darko, Drew Barrymore’s character, Donnie’s English teacher, is obviously modeled on my eleventh grade English teacher; whereas in Wallflower, the points of contact are more about The Rocky Horror Picture Show and The Smiths — but the sense of connection is real nonetheless.

Both these movies are about alienated youths. Both are set in the suburbs of mid-sized Eastern cities, Richmond in Darko and Pittsburgh in Wallflower. One takes place in the late 80s, the other in the early 90s. And both are, in a weird way, almost (if not quite) superhero stories.

Some Sort of Superhero

Donnie’s heroism begins in a very small way. Gretchen, the new girl at school, is being harassed by the local bullies and Donnie happens by.

“Do you want to walk me home?” she asks.

“Sure.”

It’s the beginning of a friendship, a romance. He asks why she moved to Middlesex, and she tells him that her stepdad tried to kill her mom, stabbing her repeatedly. Now they have a restraining order and had to change their names. Her stepfather has “emotional problems,” she tells him with a kind of resentful scorn.

“Oh, I have those, too,” Donnie replies, too eagerly.

Donnie suffers hallucinations, which turn out to be premonitions. He has an imaginary friend, Frank, “a six foot tall bunny rabbit” with a skull for a face, who Donnie sometimes sees when he looks in the mirror. Frank tells Donnie that the world will end on Halloween. Frank also tells Donnie to vandalize his school, leads him to find and take a handgun, and has him set fire to the house of a cloying inspirational speaker. (When firefighters arrive at the house they discover “a kiddie porn dungeon”; the guru is arrested, and Donnie escapes.) Later, on Halloween, Donnie saves a senile old woman from some hooligans who break into her house, but Gretchen dies as a result. Then, by arranging himself to be pulled into a time vortex — he sacrifices himself and saves the world.

“Donnie Darko?” Gretchen says, incredulously. “What the hell kind of name is that? It’s like some sort of superhero or something.”

Donnie smirks. “What makes you think I’m not?”

Psychos Together

Less bleak, and more solidly realistic, The Perks of Being a Wallflower is a sweet movie, even a bit sentimental. It’s as much about friendship as loneliness, as much about belonging as alienation.

Charlie is a freshman, friendless, “the weird kid who spent time in the hospital.” He’s shy, he’s lonely, he’s bullied. He thinks that “high school is even worse than middle school,” until he makes friends with a pair of seniors, Sam and her stepbrother Patrick, and they bring him into their circle. “Welcome to the island of misfit toys,” Sam says.

After that, Charlie spends the rest of the year hanging out, suffering through a bad-idea-from-the-start first romance, taking drugs, reading A Separate Peace and A Catcher in the Rye, helping Sam study for her SATs, going to Rocky Horror, and basically doing normal high school stuff — normal, anyway, for weird kids in the early 90s. Of course Charlie isn’t really a normal kid. His best friend killed himself a few months earlier, and since then he’s been seeing things, hearing things, and always just about two steps away from a breakdown. Most of the year he keeps it under control. His friends help to keep him sane.

But then one day in the cafeteria —

A jock trips Patrick, and another calls him a “faggot,” and soon there is a fight. Kids gather around to watch, in the appalling way they do. What we know, but they don’t, is that one of these jocks is Patrick’s lover.

Three football players pull Patrick off their friend. Two hold his arms, and a third punches him again and again. Charlie is rushing toward the fight when everything slows down, becomes distorted, and goes black. A moment later, all the kids are staring at him and everyone is quiet. The bullies lay on the ground, obviously hurt. Charlie looks down and sees that his knuckles are almost black with bruises. The other kids look at him with a kind of amazed horror.

“I can’t really remember what I did,” he confesses later.

“Do you want me to tell you?” Sam asks. “You saved my brother. That’s what you did.”

But Charlie doesn’t feel like a hero. He feels like a monster, a freak. “So you’re not scared of me?” he asks, nervously.

Sam looks at him then with a combination of pity and gratitude. She looks at him with love. “C’mon,” she says. “Let’s go be psychos together.”

Tear Us Apart

Alienation and friendship, the heroic and the monstrous — these things are tied together. Love is most precious precisely where alienation is most acute. And sometimes, perhaps, our friends are just those people who can see what is heroic about the parts of ourselves that are most monstrous.

Also, for both Donnie and Charlie, it is love for their friends that inspires their heroism. Charlie spends most of a year being bullied by older, meaner kids, but he only hulks out when he sees his friend is being hurt. Donnie deeply hates the place he lives and the people around him. He wants, at least subconsciously, to destroy it all — to “burn it to the ground.” In the end, he is the hero, the savior — but he might not have been.

Donnie is also identified, earlier in the film, with the adolescent vandals in Graham Greene’s story “The Destructors,” which his English class is reading. In the story, young men break into a house and destroy it, in part by flooding it with water. Donnie, then, in a kind of psychotic sleepwalking trance, breaks into the school and opens up a water main, then attacks a statue of the mascot with an axe. Discussing the Greene story in class, Donnie is asked why he thinks the boys trashed the house. “Destruction is a form of creation,” he quotes (with echoes of Bakunin).3 “They just want to see what happens when they tear the world apart. They want to change things.” Donnie can sympathize. Throughout the movie he is at odds with various types of authority — teachers and principals, parents, his therapist, the creepy pop-psych-Christian motivational speaker — as well as school bullies, his sisters, and sometimes even his friends. His whole suburban, Republican, private school, country club, psych med world is suffocating and oppressive — and yet he acts to save it.

Donnie can only be reconciled to this world through his death. But that is a choice, which he could make or refuse. He can save it if he chooses, and life will continue much as it was, but without him. Or he could end it all, simply by doing nothing.

I think that Donnie embraces his role, not (or not just) as an elaborate form of suicide, and not to save the world in a metaphysical sense, and surely not to save the world in the narrow social sense in which he inhabits it, and probably not even to save his family — but to save Gretchen. It is not until she is killed that he races toward the wormhole and when he reaches it, and finds himself in bed, weeks earlier, waiting for the mysterious accident — a jet engine that crashes into his room — to kill him. He offers a victorious laugh. Donnie Darko does not die for our sins; he is not trying to save the world. He dies for the love of one girl, which is more heroic in its way. He trades his life for hers. “Love will tear us apart” plays in the background.

Tunnel Songs

In Darko, the soundtrack is almost a kind of narration. Echo and the Bunnymen and The Church weave together themes of fatalism and free will (“Leads you here despite your destination”; “Fate/Up against your will”), while Gary Jules and Micheal Andrews (with their cover of Tears for Fears’ “Mad World”) also incorporate those feelings of banal desperation:

“All around me are familiar faces

Worn out places, worn out faces

Bright and early for the daily races

Going nowhere, going nowhere

…Went to school and I was very nervous

No one knew me, no one knew me

Hello teacher, tell me, what’s my lesson?

Look right through me, look right through meAnd I find it kind of funny

I find it kind of sad

The dreams in which I’m dying are the best I’ve ever had”

All three of these songs — given their desolate tone (“loveless fascination,” “So cruelly you kissed me”), their nocturnal imagery (“the killing moon,” “under the milky way”) , and even the name of the band Echo and the Bunnymen — seem like they could have been written for the film. I suspect that is because Richard Kelly managed to convey cinematographically the sullen, gloomy mood of 80s New Wave, and to remember the way such music does — or at least did — serve as the soundtrack for the lives of a certain type of adolescent, touching their deepest feelings, echoing their secret thoughts.

Music is a plot point in Wallflower. Charlie listens to The Smiths’ lullaby/suicide note “Asleep” almost endlessly, and puts it (twice) on a mix-tape for Patrick. It conveys a sense of depressed, lonely surrender (“Deep in the cell of my heart, I really want to go”), followed by the dream of “another world. . . a better world.” The song reflects the duality of alienation and rebellion, as does another featured prominently in the film — David Bowie’s “Heroes.” The three friends — Charlie, Patrick, and Sam — listen to “Heroes” while they drive through a tunnel, late at night. Sam stands up in the back of the truck, arms out, the wind in her face. It feels like flying. It feels, as Charlie puts it, “infinite.”

Later, after his breakdown, Charlie receives a note from Sam. “I know you will come flying out of the tunnel,” she writes, “and feel free.”

Both of these songs — “Heroes” and “Asleep” — find a kind of victory in defeat, but the emphasis is reversed. Where Morrissey is resigned, Bowie is defiant:

“Though nothing will drive them away

We can beat them, just for one day

We can be Heroes, just for one day”

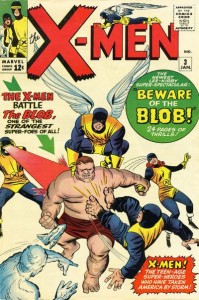

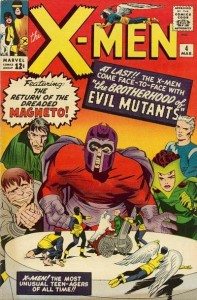

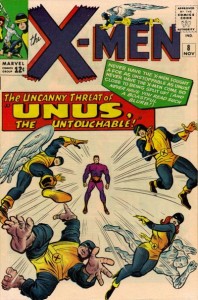

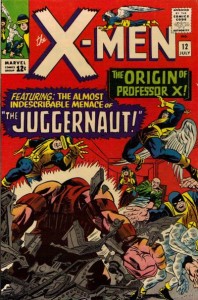

Dangerous Gifts

It’s no secret that superhero stories are often a kind of adolescent fantasy: the weak become strong; the outcasts, triumphant. But they are only fantasies, and in the real world the pressures of adolescence are less likely to result in mutant superpowers, and more likely to produce psychosis. It may be that the kind of psychosis we see in Donnie Darko and Perks of Being a Wallflower is just a hypertrophied cinematic portrayal of normal adolescent alienation, that to represent the depth and the gloom of the feeling, we need to connect it to madness and violence, which do, after all, often feel so closely related. If so, then these movies are a darker, more fearsome reflection of the superhero fantasy. Our adolescent selves may long to be like Spiderman or the X-men, but we feel like Donnie and Charlie. In fact, we long for the former because of the latter. The fantasy is a response to the fear.

Darko and Wallflower pull this transference back in the other direction. Here the outcast is the hero; the weakling and the freak really do save the day. Charlie does it, in part, by incorporating the fantasy into his reality (“Don’t dream it, be it”); he addresses his journal to an imaginary friend. Donnie does so by fully entering the fantasy. He follows the rabbit; he goes through the looking glass. What he finds, as a result, is more real than his wealthy suburb and his private school — at least it is more real to him.

The metaphysics of Donnie Darko are complex. It is not simply a time-travel story. Instead, as explained (or at least theorized) by a book Donnie’s teacher loans him, The Philosophy of Time Travel, most of the story occurs in a “Tangent Universe,” which has spun off from the normal universe. It is, as the book puts it, “highly unstable,” and when it inevitably collapses, rejoining the standard time stream, it risks “destroying all existence.” Though the mechanics aren’t entirely clear, this catastrophe can be averted, through the intervention of a figure called “The Living Receiver”:

“The Living Receiver is often blessed with Fourth Dimensional Powers. These include increased strength, telekinesis, mindcontrol, and the ability to conjure fire and water. . . . The Living Receiver is often tormented by terrifying dreams, visions, and auditory hallucinations during his time within the Tangent Universe.”

Donnie easily recognizes himself in this description, and he does in the end take on this role and save the world. He dies, the Tangent collapses, and the events of the previous month are erased. The world does end, but only this other world, which no one recalls. Or, put another way: The world does end, but only for Donnie. He is a sacrifice, and no one knows it. The clock turns back. Gretchen has never met him. But some of those he saved suffer nightmares, visions. Is it guilt for his death? Or has his alienation somehow spread out, touching the community as a whole?

Secret Identities

Like superheros, all adolescents lead double lives. It is almost as though they inhabit two only partly overlapping worlds. There is the world of their parents, and school, and church, debate club and organized sports. And then there is the world of their friends, with drugs, and swearing, and cutting class, staying out all night, loud music, teen drama, bullying, and fights. It’s the second world, from the kids’ perspective, that is the real world. That is the world where things happen, where it matters. Sometimes those worlds are at war. And sometimes the first is just a prison to contain the second. But sometimes the first is a mask that the second wears, not to protect itself, but for the benefit of the adults it fools. It provides an illusion that our children are safe, sane, and happy — and when the illusion fails, we ask ourselves sadly what is wrong with them. Donnie’s therapist tells his parents: “Donnie’s aggressive behavior — his increased detachment from reality — seems to stem from his inability to cope with the forces in the world that he believes to be threatening.”

But maybe there’s nothing wrong with these kids, or nothing special. Maybe it’s just the world we’ve given them.

Toward the end of Wallflower, Charlie has a more serious break. He remembers his aunt, his “favorite person in the world” abusing him as a child, and it is tied, in his mind to her death in a car accident a short while later. He blames himself: “I killed Aunt Hellen, didn’t I? . . . What if I wanted her to die. . . ?”

When he wakes up, he is in the hospital. He tells his psychiatrist: “There’s so much pain, and I don’t know how to not notice it. . . . It’s everyone. It never stops. Do you understand?”

She might, she might not. What she tells him is, “We can’t change where we come from but we can choose where we go from there.”

It’s a happy ending. Which is to say, it’s a good start.

_____________

1. I am writing specifically about the director’s cut: Donnie Darko: The Director’s Cut, written and directed by Richard Kelly (Newmarket, 2004). The basic argument would still apply to the theatrical release, but some details I mention might be different.

2. Here I am writing about the film, not the book (which I haven’t read). The Perks of Being a Wallflower, written and directed by Stephen Chbosky (Summit Entertainment, 2012).

3. “. . . destruction after all is a form of creation. A kind of imagination had seen this house as it had now become.” Graham Greene, “The Destructors,” Complete Short Stories (New York: Penguin Books, 2005) 10.