“I know a woman whose internal electrical field escapes autonomously. Her basal low level charge kills small batteries: watches, pagers. Her moderate level charge creates worse havoc, even the death of computers. She has high charge levels, as well. The electrical system of at least two cars have not survived the rare but severe escapes of her internal charge.”

The above woman is my mother, writing about herself in third person. I found several print-outs of the passage while emptying filing cabinets in her condo this summer. She moved into assisted living after being diagnosed with moderate Alzheimer’s last spring. The paper was dated over a decade ago. It continues:

“Not too long ago she learned about her grant submitted to NIH (National Institutes of Health) to fund her Health Disparities research. Despite an excellent 172 priority score, the interim Director of the Institute had skipped over her grant and funded others with less meritorious scores. An appeal process is not part of the NIH Policies & Procedures.

“Hours later, the microwave fan came on autonomously. As she watched the power lights on her laptop, they cycled between battery and house power. The big computer turned itself off autonomously as she learned later. They had both been mortally damaged.

“She sat quietly in the light of candles she had made, as far as possible from electricity-powered items. Feeling drained, she went to bed.”

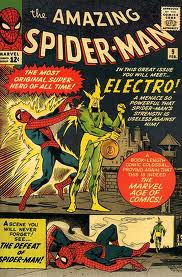

I had read this before and had heard my mother describe such electrical incidents multiple times. It would be familiar even if she hadn’t. It’s a standard comic book trope. When Stan Lee and Steve Ditko created the supervillain Electro for Amazing Spider-Man #9 (1964), they sent Max Dillon, an electric company lineman, up a utility pole to be struck by lightning while holding two lives wires. This transforms him into a human capacitor.

My mother’s explanation is more vague and so perhaps more plausible. “If you have ever lived with a cat,” she writes, “then you know that sometimes something fires off its plum-pit sized brain, and it suddenly becomes manic, running crazily throughout the home, yowling. Cats have been used in neurological research (unharmed) as their brain’s electrical wiring is remarkably similar to that of humans. Our brains operate autonomously to maintain the functions of our organ systems, breathing for example. As the human brain does so, electrical impulses skip along and bridge synaptic nerves via neuro-electrical transport systems not yet totally well-understood. Drugs have been developed from research in cats (and from other types of research) that modulate either uptake or release of neuro-transmitters, and thus are used to treat clinical depression and anxiety.”

Under “aspects of this woman which may or may not be relevant,” my mother includes: “deep, encompassing dyslexia; decades of treated clinical depression; creativity characterizes both her medical research and artistic pursuits; in an emergency, she is calm, focused, and solution-focused without conscious thinking.”

In other words, my mom thinks she’s a mutant. She was born with a dyslexia/creativity-related electrical capacity that was tapped and/or augmented by anti-depressant medication, resulting in uncontrolled and unpredictable short-circuiting discharges. I’m tempted to call her Electra Woman, from the 1976 Krofft Supershow, one of the few Saturday morning programs I didn’t watch as a kid (perhaps because it ran opposite The Shazam! / Isis Hour). But Electra Woman didn’t have superpowers; she just operated a multi-functional ElectraCom, just the sort of gadget my mother would have fried.

“Last night on the way home from work,” she writes, “the car dome light stayed on all the way. I called my beloved engineer—not home. So I tried a new technique. Brute force with my shoe—on the handle which controls all car interior lights—worked quite well.

“There is an unrelenting curiosity about when the next electron-associated event will occur. There is no doubt that such will be the case.

“The only question is when.”

Although I’m skeptical of my mother’s mutant abilities, I did discover a final piece of evidence in her condo. The professional-grade shredder she had bought to destroy her decade-old and so now obsolete NIH research was dead. Her filing cabinets included reams and reams of health surveys, all of which had to be shredded to preserve the privacy of the responders. I drove to Staples to buy a new one.

“At this time I am working on too many innovative manuscripts. There is a skim of anger coating me because I am unable to clone myself. I grow concerned that if I were to concentratedly focus my electrons on an appropriate target—such as the car of a particular individual who could find me a way to funding for someone to help me with all these manuscripts (i.e. type in WORD which has never cooperated with me, or got to the library to find and copy the references I need, etc.) I think I could destroy all things electrical in his car. I wonder if I will be able to contain myself.”

Electra Woman had Dyna Girl for a helper. My mother has me. I took over her bank accounts, found her an assisted living facility, put her condo up for sale, haggled with a buyer. I’m a great sidekick. I used to work in her lab summer between semesters, spinning blood samples in her centrifuges, logging data in her computers. There was never an accident, no power-bestowing explosion, nothing transformative. If I inherited any of her mutant genes, they are irredeemably dormant. My laptop works fine.

Warner Brothers shot a new Electra Woman pilot back in 2001, about when my mother lost her grant renewal and so her career as a medical researcher. It featured the washed-up superheroine drinking and smoking alone in her cluttered trailer–until a new Dyna Girl rescues her from her depression. The series wasn’t picked up, but I watched the unaired pilot on YouTube after a night of shredding. My mother told me the next day:

“It feels like a part of me has been ripped out.”

She is now contained in an assisted living studio, where med techs sort and deliver her anti-depressants and other pills every morning and evening. In the comic book version, a final fit of rage would uncap her well of superpowers, and she would rampage through the building and out into the streets to savage the city, until subdued by some friendly neighborhood do-gooder.

Instead she’s sitting in her one-room apartment with her cat, reading and smoking as the magic of her neuro-transmitters continues to peter out.