Mickey Mouse in Korea, onstage for Kim.

The Disney corporation did not give Korea permission to use their creations and one can only begin to imagine how Kim saw this interaction playing out. Perhaps he too is living in the fantasy world that Baudrillard presents. Inevitably Disney will ask for payment. But it perhaps hints at the dictator’s desire to put Baudrillard’s theory to work and to conceal his own brutal government with the warm and fuzzy.

Elsewhere, in Moengo, Suriname, Netherlander artist Wouter Klein Velderman built a giant wooden Mickey, assisted by local artists who carved totems into the legs. This inclusion Klein Welderman felt, somehow made it possible for the people to feel some autonomy in the coming industrialization of their country. The piece is entitled “Monument for Transition.” It is his warning of what they are to expect. What ever his motivation, Disney is now a real wooden artifact, standing securely on the cultural icons of Moengo’s heritage.

Moengo, which has only recently put a violent civil war behind it, needed to be warned by the presence of the Mouse. A little farther north at the Lone Star Performance Explosion, Houston’s International Performance Art Biennial, the Non Grata performance group donned latex Mickey hoods/masks and trashed a car with sledge hammers and explosives. I have to admit that this piece probably has more impact live and that I’m kind of delighted by the vigor of their gesture. But I want to draw attention to how Baudrillard’s once extraordinary theory has achieved in certain circles a common acceptance.

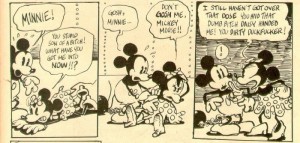

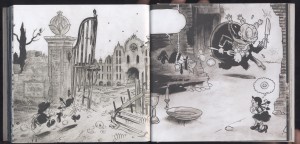

The early postmodern up-side of this if you will, is that bursts of anti-Mickey propaganda emerge from the margins to remind us of just where we really are. These various incursions into Disney property found early expression in the totally subversive and inspired Air Pirates work.

In these strips, Minnie and Mickey are caught in unguarded moments. We see their life behind the spotlights. Of course, this only adds another layer of confusion, because these comics fracture an imaginary world, but for a moment the reader is able to say “I knew that they were really like that all along.”

But if Baudrillard sees us living in a delusional state, Fredric Jameson in his 1991 essay “Postmodernism or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism” sees us experiencing a kind of schizophrenia. He elucidates his view of our affectless culture, which he suggests is built on the edifice of the late stage of capitalism. He writes of the parameters of his project:

I have felt, however, that it was only in the light of some conception of a dominant cultural logic or hegemonic norm that genuine difference could be measured and assessed…The postmodern is, however, the force field in which very different kinds of cultural impulses – what Raymond Williams has usefully termed “residual” and “emergent” forms of cultural production – must make their way. If we do not achieve some general sense of a cultural dominant, then we fall back into a view of present history as sheer heterogeneity, random difference, a coexistence of a host of distinct forces whose effectivity is undecidable…The exposition will take up in turn the following constitutive features of the postmodern: a new depthlessness, which finds its prolongation both in contemporary “theory” and in a whole new culture of the image or the simulacrum; a consequent weakening of historicity, both in our relationship to public History and in the new forms of our private temporality, whose “schizophrenic” structure (following Lacan) will determine new types of syntax or syntagmatic relationships in the more temporal arts; a whole new type of emotional ground tone – what I will call “intensities” – which can best be grasped by a return to older theories of the sublime; the deep constitutive relationships of all this to a whole new technology, which is itself a figure for a whole new economic world system.

Jameson later discusses how a postmodern sublime encompasses the relentlessly promulgating cultural media; film, TV, internet and electronic gadgets of all kinds, which destabilize our sense of self and fracture our psyche. In the arts, he sees only reproductions, which no longer parody their models, but rather that are affectless pastiches which offer nothing but a reflection of the citizen, who is now beyond-disaffected, beyond the neurosis of the existentialist, beyond all expressionist’s anxiety and finally in a dazed state of psychosis.

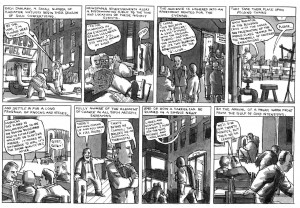

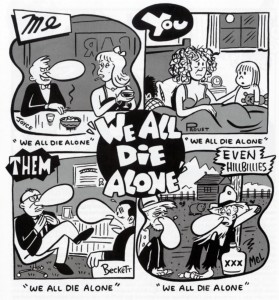

Jameson points out that the sublime of postmodern is not the dark and brooding place of the high romantics; it is not the depressed world of brooding heroes. Somewhere along the line, all of that angst and personal introspection has been replaced by another world of bright shiny surfaces, replicas and fragmented visions in a world now experiencing another kind of psychic onslaught. Jameson talks about the postmodern sublime as a type of container for all this madness, which he describes as a type of schizophrenia. Some comic artists were ahead of this curve. Newgarden seems to have nailed it, along with his cohorts at Raw. In part under the intellectual guidance of Francoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman, the french philosophical influence is evident in their editing.

Early Postmodern Shinings.

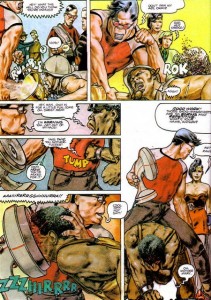

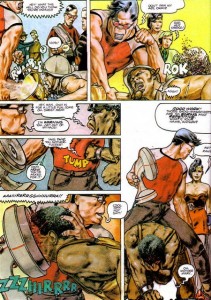

In a particularly postmodern way, a new insanity entered the pages of comics and schizophrenia became the new model.I still remember my first encounters with Stefano Tamburini and Tanino Liberatore’s (Rank Xerox) Ranxerox in 1978 and how I was still shocked by the unaffected violence.

Ranxerox was a mechanical creature made from Xerox photocopier parts and there was a randomness in his acts of violence that seemed to have no self-consciousness, no motivation and suggested a different sort of sociopathic absence of rationality. He was in fact, the embodiment of the age of mechanical reproduction. His violent acts were simply there, monstrously accumulating on the pages and refusing to be contained in any prior system of logic. His surfaces were shiny and he appeared smooth as if airbrushed into reality; he was alternately sexual and violent.

Ranxerox by Stefano Tamburini and Tanino Liberatore

The pantone pen technique used brought the character to life in a way that separated Rank from the art of the fumetti style Italian horror comics, such as Satanik and its predecessor Fantomas by Alain and Souvestre. The reader and the characters in these comics were aware that certain boundaries were being crossed, as they engaged and became archetypal villains, whereas in Liberatore’s world the characters remain largely oblivious.

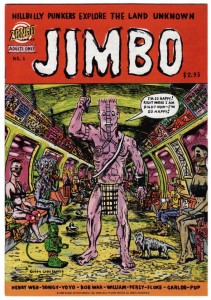

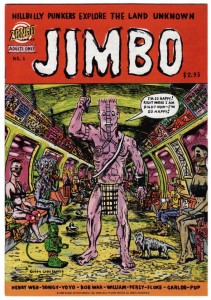

Another train rider of the early postmodern is Panter’s Jimbo, whose blank ferocity reflects perfectly the explosion of media and the madness of everyday life. Jimbo lives surrounded by shakily drawn monsters and aliens. His reality environment sits between the real and the unreal.

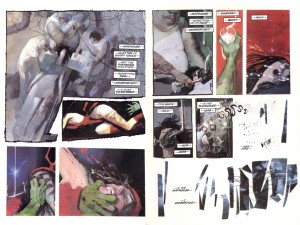

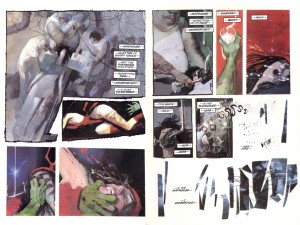

Several years later in 1986 American bred, Elektra: Assassin, came to vivid and stylishly bloody life in the hands of Bill Sienkiewicz. With Frank Miller’s script, her madness was eroticized and melded with uncontained and unconscious violence. Elektra, an understood schizophrenic, is seen in her hospital room, incapable of managing her life. Unclear as to what or who she is (and of course this is Miller nailing the post modern condition) while she pursues her day job as assassin and her nights are spent in the confines of the institution. Her mental state is depicted as something more akin to her natural condition. Sienkiewicz’ art is a tour de force of photocopy, parody/pastiche and repetitions.

Sienkiewicz in what promised to be a new life for mainstream comics, used different mediums and techniques that both reflected technological advances and presented a comic that drew inspiration from myriad sources. The art is constantly changing its style and represents a reaction to the seeming explosion of new media as computers, satellites and early cell phones accelerated communication.

However, as Jameson also notes in his essay, boundaries are no longer held in check by any social mores, because we have been saturated and inured to images of violence, sex and those things that were once held distasteful since we have been institutionalized and sanctioned as part our lives. Jameson writes about this cultural numbing:

As for the postmodern revolt against all that, however, it must equally be stressed that its own offensive features – from obscurity and sexually explicit material to psychological squalor and overt expressions of social and political defiance, which transcend anything that might have been imagined at the most extreme moments of high modernism – no longer scandalise anyone and are not only received with the greatest complacency but have themselves become institutionalised and are at one with the official or public culture of Western society.

The Late Postmodern or the Post post modern even.

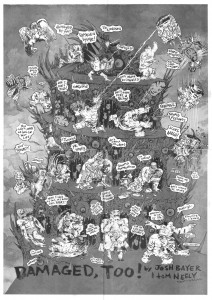

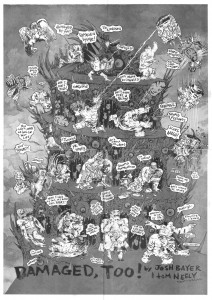

Josh Bayer and Tom Neely depict beings who no longer feel while other cartoon characters look out from the “secret prison” of Black Flag’s song. Nancy, Wimpy and Little Orphan Annie, Krazy Kat, Jughead, Mutt, Jeff, Goofy and Mickey peer out from behind bars while troubled figures lament how they have been ruined by comics and how they no longer can feel anything. The past exists in the sampled figures of cartoon culture. Dante is trampled underfoot and we are given a post-postmodern hell. These images of madness question where we exist after the punishment of the cartoon, what circle of media hell is home for us once we are conscious. This is the schizophrenia of the postmodern that Jameson describes.

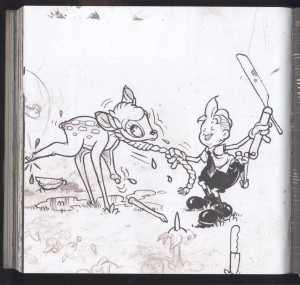

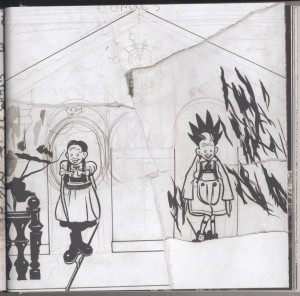

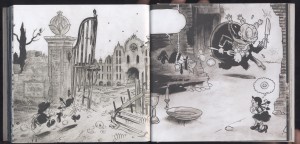

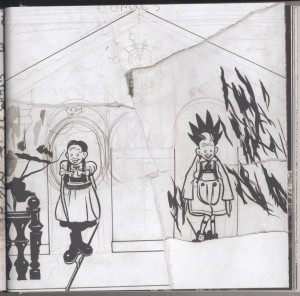

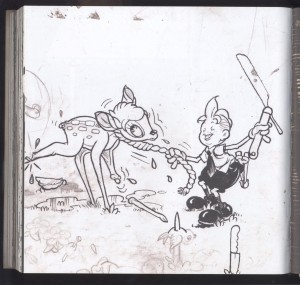

Al Columbia’s Pim and Francie perhaps sums it all up. They run not walk to the sanatorium. Columbia’s characters are no longer in revolt, they are beyond that cognitive choice. Rather they live in a world that does not differentiate morality and feelings. Columbia draws snatches from various artists styles. They hover ghostlike, pulled back from our collective memory as they sit on pages that are torn, fragmented and abused in a confrontation of what it means to be a new product. Jameson suggest that nothing is left to shock us, but I’d suggest that Al Columbia does just that. In this final image the boy takes a straight razor to Bambi. He eschews the choice of Mickey and assaults us in the soft spot. Bambi, the sacred lamb, the sacred cow, the holy sanctified symbol of innocence, is offered to the madness of the postpostmodern. Bambi’s limbs lie dismembered in the grass and we are oh so close by, to see them.

[1] http://www.deseretnews.com/article/765588670/Mickey-Mouse-takes-N-Korean-stage-in-show.html

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/northkorea/9385901/North-Korea-Kim-Jong-un-enjoys-unauthorised-Disney-show.html

[2] http://wouterkleinvelderman.blogspot.com/