It was August in Arizona and the heat was punishing. To escape it, a friend and I went to see a movie — Hannah Arendt. The film centers, not (as one might expect) on Arendt’s relationship with Heidegger, but on her coverage of the trial of SS Lieutenant Colonel Adolf Eichmann and her argument that, in his case, evil consisted not of malice or personal cruelty, but of allowing himself to be converted into an instrument for “an enterprise whose open purpose was to eliminate forever certain ‘races’ from the surface of the earth.” Here was evil, not as a Miltonian Lucifer, but as a Weberian bureaucrat. It was not romantic, it was banal. It was not rebellious, it was obedient. In fact, one might say that Eichmann’s evil was his obedience. He was responsible for so much, because he took responsibility for so little.

The next day, we drove a small distance from Tucson to visit the Titan Missile Museum. We were issued blue hard hats, and we toured the underground bunker, read the plaques explaining the theory of Mutually Assured Destruction, and watched as children simulated the launch sequence. Finally, we peered down into a silo, staring at the nose of a (now disarmed) ICBM. It was like staring into the barrel of a gun, but a gun pointed at the entire world. The tour guides were good-natured old men, who (I was later told) had all worked in some capacity on the construction or maintenance of the base. And the tone was a weird blend of duty-bound righteousness and nostalgic kitsch. The attitude was, “We saved the world from Communism, by God; now you can buy hammer-and-sickle patches as souvenirs.”

I left the base feeling a kind of sick dismay. I was reminded of my childhood at the twilight of the Cold War, the spy movies, my G.I. Joe’s, and 99 Red Balloons on the radio. I remembered the playground debates about whether it would be better to live in an irradiated wasteland or be incinerated instantly. I thought about how much my life was shaped, without my really understanding it, by these missiles, less than a minute from take-off, and the similar missiles, equally ready, somewhere in the USSR. It seemed to me, not only evil, but actually insane, and what was worse, a system of insanity — or two parallel systems, relying on innumerable men to maintain them. Maintaining them meant, in effect, preventing war by deliberately keeping us at the brink of extinction. The entire world was held hostage by two forces whose only demands were that we remain their hostages. It couldn’t possibly last. Standing at the edge of the silo, looking at that long, blunt rocket, I was sure of it. The idea was to save the world using a system designed to destroy it. It couldn’t work.

But of course it did. Mutually Assured Destruction worked. Neither side dared use their weapons knowing that the consequences would include their own annihilation. Or maybe neither side ever intended to use them, and it was just a shared paranoia that kept us at the edge of destruction for an entire generation. Either way, Communism fell, the Cold War ended, neither superpower fired missiles except within their own territory. Peace is our profession; exit through the gift shop.

False Alarm

Things did not go so well in Eugene Harvey and Burdick Wheeler’s novel Fail-Safe. An off-course airliner triggers a scramble of jets, which are then recalled once the plane is identified. The whole incident should have been routine, but a mechanical failure results in one bombing group — nuclear-armed and heading to Moscow — getting an irreversible go-ahead.

As the planes move toward their target, several small dramas unfold simultaneously. Presidential advisors argue for and against launching a full attack before the Soviets can respond. Military commanders try desperately to contact the crew and persuade them to abort; they then send the nearest fighters after them (pointlessly: with insufficient fuel, they crash into the Arctic Sea); they finally provide the Soviets secret technical information to aid in their defense. And the American President and the Soviet Premiere confer and reason together and negotiate to try to avoid Armageddon. (The President is unnamed throughout; he is played by Henry Fonda in the 1964 film, and Richard Dreyfus in the 2000 television production. The Premiere is identified as Khrushchev.)

The technical and the military solutions fail, and in the end it comes down to the negotiations. The problem is that both world leaders are trapped by the logic of the overall system. If the Russians hesitate in their response, it would leave an opening for a full offensive attack, should one be coming. And if the Russians counterattack, the US must also launch its missiles, for exactly the same reason.

Neither side can allow an attack to go unpunished, without exposing themselves to worse. The theory of Mutually Assured Destruction demands that the threats on both sides be credible. Nobody can afford to deescalate.

“‘I am trapped, Mr. President,’ Mr. Khrushchev said. His voice was riddled with despair. ‘I am perfectly prepared, Mr. President, to order our whole offensive apparatus to take action. In fact, I intend to do precisely that unless you can persuade me that your intentions were not hostile and that there is some chance for peace.’ . . .

“‘I am aware of that,’ the President said. ‘But I will do anything in my power to demonstrate our good will. I only ask that you not take any irrevocable step. Once you launch bombers and ICBMs everything is finished. I will not be able to hold back our retaliatory forces and then it would be utter devastation for both of us.'”

In the end, the President offers a solution. If the bombs reach Moscow, he will order a near-simultaneous attack on New York — “four 20-megaton bombs. . . in precisely the pattern and altitude in which our planes have been ordered to bomb Moscow.” It will prove to the Russians that the bombing was accidental, meet the need for a proportionate response, but avoid the escalation toward full war. The President reasons: “We will each have lost our largest city. But most of our people and our wealth and our property and our social fabric will remain. It is an awful calculation. I could think of no other.” The Russian Premier soberly accepts the offer, and that is just what happens. Having destroyed Moscow by mistake, the President destroys New York deliberately, and the world is saved.

Staged Attack

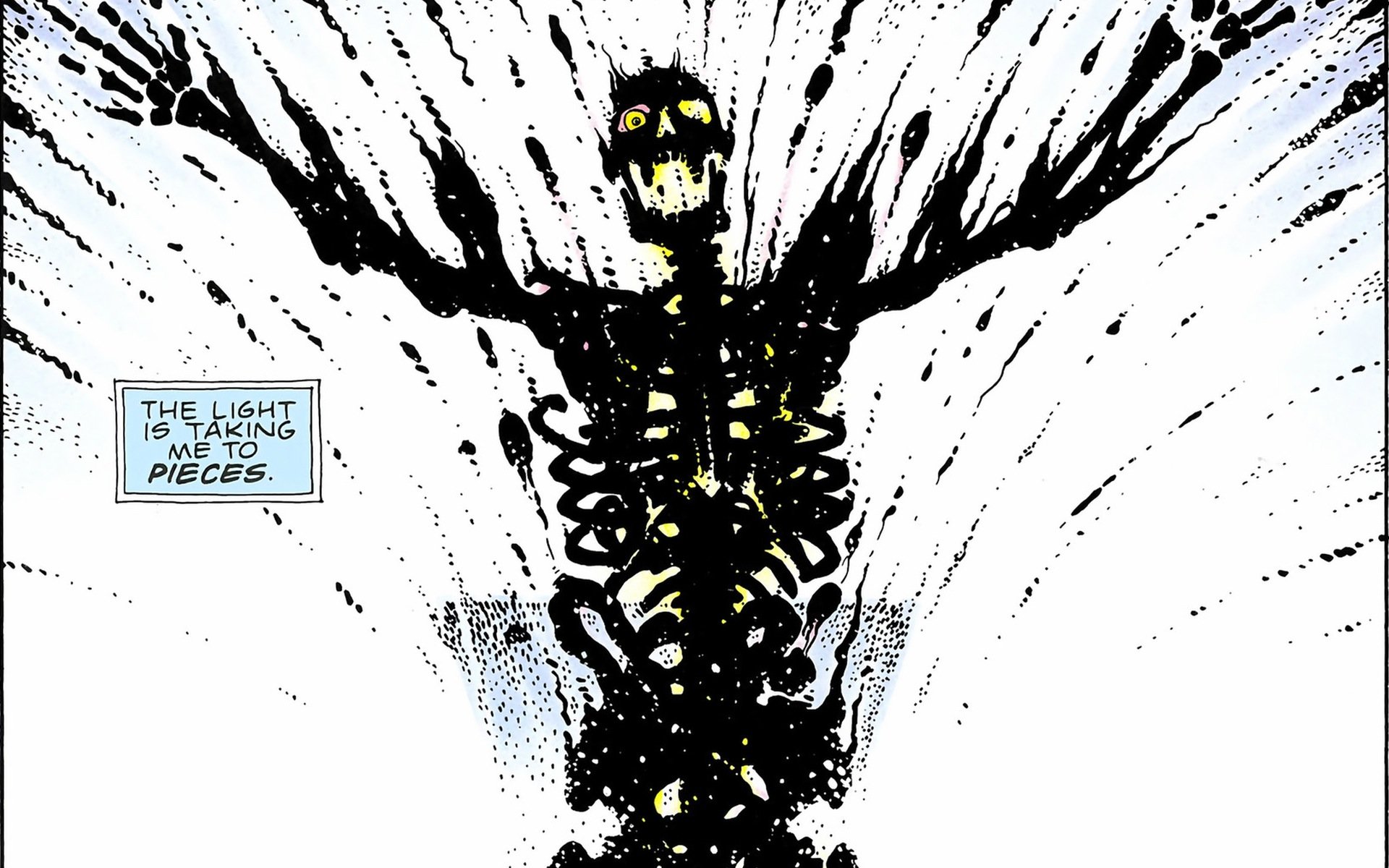

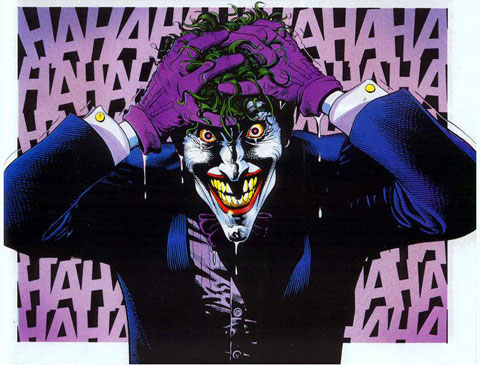

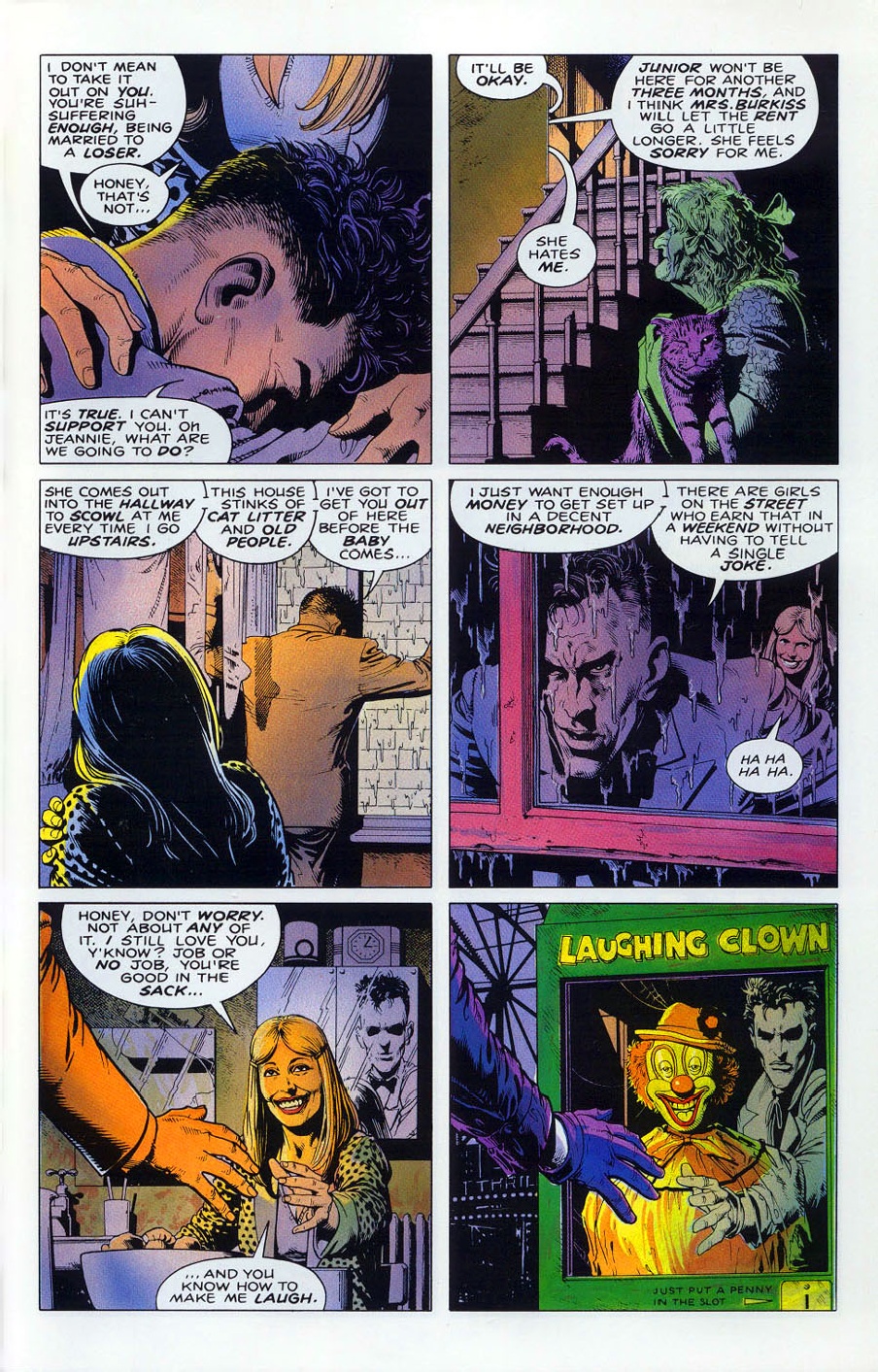

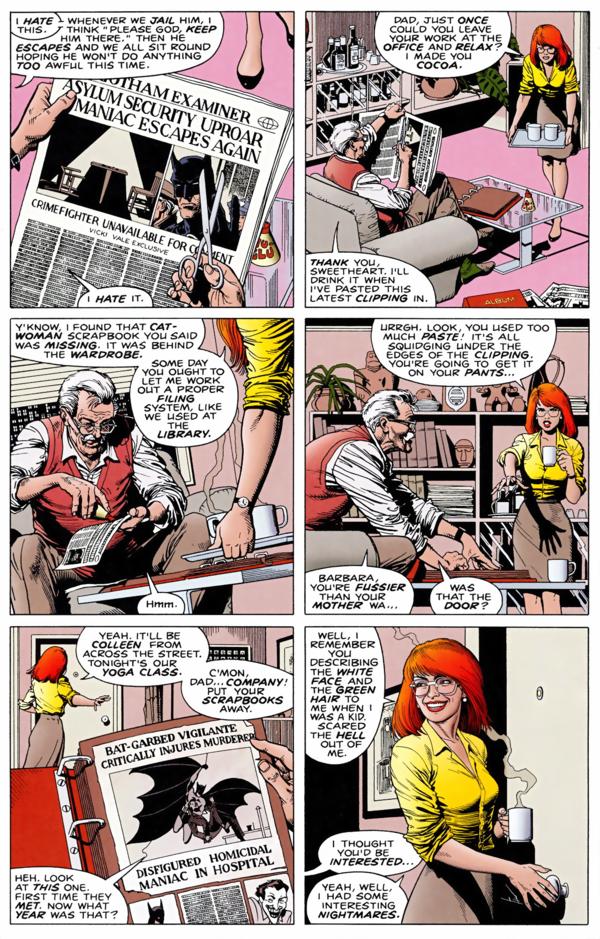

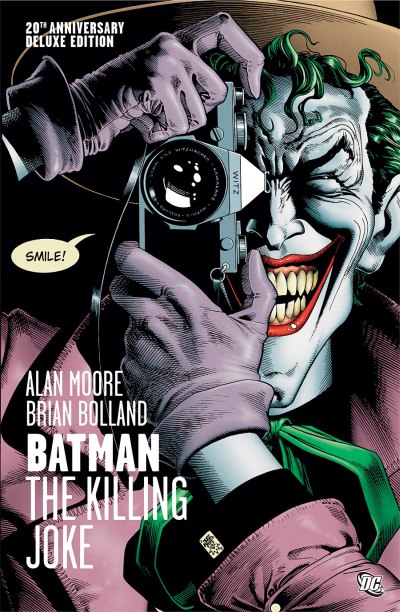

New York is similarly lost, and the world likewise saved, in Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s graphic novel, Watchmen. As the US and USSR lurch toward nuclear war, the super-genius Adrian Veidt — a.k.a. Ozymandias — launches a faux inter-dimensional alien attack against New York, thus terrifying the superpowers into uniting against the common enemy and initiating a new era of global peace.

Veidt seems to have understood, as all sane people should, that if we continuously prepare to kill one another, eventually we will kill one another. But his genius lay in his solution to the problem. Rather than appeal to reason or morality, he instead mobilizes the fear that leads us toward Mutually Assured Destruction, directing it instead against an outside threat. Fear then becomes the motive for peace rather than for war. Our belligerence is directed against a fictitious enemy, so the outbreak of real hostilities is impossible.

In terms of measurable outcomes, Ozymandias’ success is greater than that of the unnamed Fail-Safe President, and comes at less of a cost. Ozymandias achieves lasting peace by destroying a single city — in fact, only half of New York — while the President destroys two in their entirely. In the novel, the President and the Premier pledge to pursue disarmament (the movie adaptations are less explicit). But the President is a tragic figure, an imperfect human being doing his best in an impossible situation. (“His face was slack, softened by despair. . . . His eyes were dark, but the pupils glittered like small pools of agony. . . . ‘We do what we must,’ he said slowly. . . . [T]he President’s face reflected the ageless, often repeated, doomed look of utter tragedy.”) Ozymandias, in contrast, comes across as a megalomaniac willing to sacrifice millions to his own self-righteous ego. Or as the Silk Spectre so concisely put it, just before trying to shoot him: “Veidt. . . You’re an asshole.”

Guilt and Grief

Why are our reactions to these characters so different?

One is tempted to suggest that it reflects a difference in responsibility. The President, by this account, is a hapless victim of circumstance; he responds as well as he could to a situation he did not create. Veidt, on the other hand, deliberately provokes the crisis to which he responds. But the President himself rejects this interpretation. In the televised version, when the Russian Premiere offers what little comfort he can — “Who can be blamed? Can you blame a machine?” — the President refuses his consolation and insists on their shared responsibility: “Men built those machines, Mr. Chairman. . . . Men are responsible for what they do. Men are responsible for what they make. We built those machines, Mr. Chairman — your country and mine.”

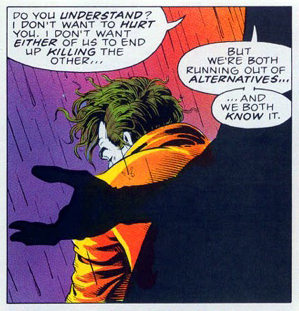

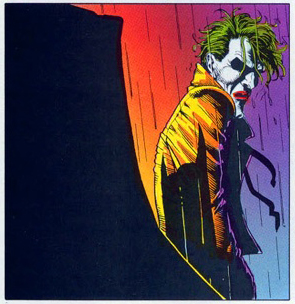

The difference between the President and Ozymandias lies, I believe, not with the fact of their responsibility, but in their different attitudes toward that responsibility. The President is uncertain, reluctant. He looks for alternatives; he asks for a reprieve. Ozymandias is perfectly confident, perfectly clear. He is entirely resolute, unwavering in his agenda. Upon seeing his plan unfold, Veidt is triumphant. “I did it!” he shouts, arms raised like a victorious athlete. The President expresses no such satisfaction. He feels, instead, guilt and grief. Ozymandias tells us, in his sanctimonious way, “I’ve made myself feel every death” — but we don’t believe him. He even kills his servants, who have remained loyal throughout and doubtless guarded many secrets before. “Do you understand my shame at so inadequate a reward?” he asks the dead men rhetorically. And it should shame him — but of course it doesn’t. It is his unbelievable egotism that motivates him, not the need to cover his tracks. Veidt eliminates his accomplices so that he need not share his “secret glory.”

Interestingly, he leaves the remaining Watchmen alive, though they also know his secret. His brilliance requires admirers. They are no less likely to reveal the truth than his servants were, but they do not share in the victory. All they accomplished, he points out, was “failing to prevent earth’s salvation.” He leaves them alive, because he has proven himself superior, and they have accepted it. That was his dream all along, not only to unite the world, but show himself worthy of conquering it. His attitude toward humanity has been, always, one of superiority and contempt.

Truth and Consequences

Another difference: Veidt, while hungry for the admiration of his fellow heroes, can only act in secret. The President must acknowledge what he has done. The public may judge it right or wrong — rightly or wrongly — but they will judge it. “‘We must sacrifice some so that others can survive,’ the President said and his voice was weary. ‘I do not know how the Americans will take my action. It may be my last. I hope they will understand.'” The President accepts responsibility, accepts that he will be judged for his actions. Veidt’s plan depends on its secrecy, not merely in its execution, but in perpetuity.

Rorschach dies because he would not accept the noble lie. He knows that this refusal means his death, that it could mean everyone’s death: “Not even in the face of Armageddon,” he declares. “Never compromise.” He accepts death. He could just as easily swear himself to secrecy and then break his oath — except that he would not. It would violate his code of ethics. Torture and even killing on a mass scale do not — he praises Truman’s decision to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki repeatedly throughout the book — but the lie would. “People must be told,” he says, and he will not lie to save them from truths they will not face. And so he dies with a secret that may yet unravel all of Veidt’s plans: he does not tell the other heroes that he has sent his journal, including his theories about Veidt, to the press — albeit to the far-right conspiracy-mongering New Frontiersman. In the end, Rorschach does, as he promised at the beginning, refuse to save the world. (“All the whores and politicians will look up and shout ‘Save us!’ . . . and I’ll look down and whisper ‘no.'”) He dies then, if not happy, at least “without complaint,” knowing he “lived life free from compromise.”

Time and Luck

Ozymandias denies the judgment of humanity, and appeals only to the near-omniscient Dr. Manhattan for approval. Veidt says:

“I know I’ve struggled across the backs of murdered innocents to save humanity. . . . but someone had to take the weight of that awful, necessary crime. . . . I did the right thing, didn’t I? It all worked out in the end.”

“‘In the end’? Nothing ends, Adrian. Nothing ever ends.”

Veidt, finally, looks disconcerted. He suffers, not from grief, but from a moment of self-doubt.

What worries Ozymandias is the question of moral luck, irremovable from his justification for his actions. For Ozymandias’ justification relies importantly his success. Reasonable people may disagree as to whether it is right to kill millions of innocent people to save billions more. But if killing those innocents fails to save the rest, then no amount of good intentions will excuse murder.

Dr. Manhattan, by insisting on a permanent uncertainty, suggests that since success is never final, the justification must remain forever deferred. Moore, subtly or not, pushes the argument one step further and suggests that, since time defeats us all, victory can only ever be temporary, and thus serves badly as a foundation for moral argument. He named this character “Ozymandias,” after all, deliberately invoking the Shelley poem by that title:

“I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare,

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Moore titles Chapter XI, in which Ozymandias tells his dying servants his life story and similarly reveals his plot to his superhero peers, “Look on my works, ye mighty. . .”. He quotes the entire inscription at the end of the chapter. But the inscription, here as in the original, carries a double meaning. The king Ozymandias declaims, “Look on my works,” referring to his conquests, his rule, and perhaps also to the statue memorializing both. The traveler and the poet, however, note that this boastful phrase has survived not only the king and his kingdom, but his dynasty, its memory, and even the sculpture itself. All that remains is a ruin, surrounded by a wasteland — the true works of power. Moore, by invoking Shelley, recalls both meanings. Veidt’s works, which we witness directly in the chapter following, are indeed dreadful. And the peace they produce, Moore’s allusion suggests, cannot last.

Sideshadows

There is another reason Veidt might doubt himself, and this would be the reason he seeks Dr. Manhattan’s counsel. For Veidt’s justification does not only rely on the contingent outcome of his actions — what in fact happens — it also relies on a counterfactual claim about what would have happened had he done otherwise. Veidt, partly guided by his own intelligence, but also convinced by the Comedian’s apocalyptic taunting (“Inside thirty years the nukes are gonna be flying like maybugs. . . and then Ozzy here is gonna be the smartest man on the cinder.”), determines that — absent extreme measures — nuclear war is “inevitable.” His theory seems justified when the Russians invade Afghanistan and both superpowers prepare for a direct confrontation. But that crisis was in fact precipitated by Veidt’s own plan, which necessitated removing Dr. Manhattan and disrupting the uneasy balance of power. (Also, let’s remember that in the real world the Soviet Union did invade Afghanistan, without unleashing a nuclear holocaust — though those events did, eventually, lead to an attack on New York.)

That Veidt himself seems to be harboring doubts is indicated by his confession that “By night. . . well, I dream about swimming towards a hideous. . . No, never mind. It isn’t significant.” What the reader can recognize, whether Veidt can or not, is that his dream is a reference to The Black Freighter, a pirate comic written by one of the creators of Veidt’s Lovecraftian alien. The story, excerpted intermittently throughout Watchmen, tells of a young sailor racing to warn his town of an impending attack from a ghostly “hell-ship.” He commits numerous horrors along the way, including the mistaken murder of his own family, only to realize in the end that no attack was ever planned and the demon vessel was only seeking to claim his soul. He reflects:

“Where was my error? . . . My deduction was flawless, step by step. . . . [But g]radually, I understood what innocent intent had brought me to, and, understanding, waded out beyond my depth. The unspeakable truth loomed before me as I swam towards the anchored freighter, waiting to take extra hands aboard.”

Between these scenes from the pirate story — the murder of the family before, and the realization of the monstrous futility and horrified guilt after — Veidt tells his servants his own life story, and kills them. Obviously Ozymandias is identified with this nameless sailor, and Moore implies that the catastrophe he averted may well have only been one of his own imagining. If this is so, then Veidt, too, despite the pride he takes in his clear-sightedness, became yet another victim of Cold War paranoia, committing atrocities to avert exaggerated threats. His plot then, and the mass murder it entails, are not only wicked, but pointlessly so.

Veidt turns to Dr. Manhattan, not only for answers, but for solace. Manhattan, however, is unconcerned with human affairs. He does not offer judgements, only predictions. “I understand, without condoning or condemning.” But perhaps by refusing to give Veidt the comfort he seeks, by leaving him to wonder, Dr. Manhattan is silently offering his own verdict.

Collateral Damage

Moore’s judgement is less ambiguous. Watchmen follows, alongside the adventures of the retired superheroes, the lives of some ordinary people: a lesbian couple, a news vendor, a young boy, a psychiatrist and his wife. Their conversations, their domestic tensions, and their jobs, run together and produce simultaneous crises, intersecting just as Veidt attacks New York. When the blast occurs, these minor characters have been confronted with an incident of quotidian violence — a couple’s fight, the sort of thing that must happen thousands of times every day in a city like New York. They die, all of them. Pages of silent gore follow.

Both Watchmen and Fail-Safe narratively bring the destruction closer and closer to the reader, but in Fail-Safe this effect highlights the sense of heroic sacrifice, while in Watchmen it only shows how detached the “hero” is.

Fail-Safe steadily draws the destruction toward the reader by drawing it toward the protagonists. Moscow, a foreign city, is destroyed, followed by New York, an American city. We know already that minor characters have family in New York, but then we learn that the President — who orders the strike — will also kill his wife in the process. And General Black, who drops the fatal bomb, not only kills his family as he does so, but commits suicide himself.

The 1964 film ends by breaking out of claustrophobic halls of power, where nearly all of the drama has unfolded, and transporting us suddenly to the city streets, where nothing special is happening. Director Sidney Lumet explained: “There are ten close-ups of the most ordinary street activity going on in New York. What was important to see was that ten little pieces of the life we had there ended at that point.”

There is no doubt that the President and the General feel the effects of their actions, and thus so does the audience. The emotional weight of the climax is provided by this sense of connection. The horror of the Watchmen, in contrast, is largely a result of Ozymandias’ cold detachment and pure utilitarian calculus. Our perspective, unlike his, is invested in the fates of individuals who perish in the attack. The newspaper vendor, the little boy, the psychiatrist and his wife, the cab driver and her girlfriend — they all die. Veidt does not know these people or care about their stories, but we do.

The notion that these people matter — even in the context of a superhero story, even in the face of Armageddon — tells us what we need to know of Moore’s opinion.

And in the end, we matter, too. In the final frame, we see a hand, reaching for — or hesitating over — a book. It is Rorschach’s journal, in the offices of the New Frontiersman. So much depends on what happens next: Will it be read and understood? or burned with the rest of the “crank file”? Will peace last? or will the lie be exposed, putting the world back on course for war? Yet the image must also remind us of our position as readers, of the book we hold in our hands — and also, of the relationship between the world we inhabit and that of the fictional story. There are no superheroes, there are no extra-dimensional aliens; but there really are nuclear bombs, and powerful people who lie to us, and secrets that cost lives.

The last line of dialogue can be read as a plea, from writer to reader, urging us to draw our own conclusions and to take responsibility: “I leave it entirely in your hands.”

The Price of Goodness

Both Ozymandias and the President are larger-the-life figures — superhero and tragic hero, respectively. Adolf Eichmann, in contract, was perfectly ordinary, entirely unexceptional. In Eichmann, Arendt said, we find, “not Iago and not Macbeth,” but discover instead the “banality of evil.”

Both Watchmen and Fail-Safe also feature this theme. The bureaucratic logic of the arms race ticks along, and innumerable people do their small part to keep it moving, if only by showing up and doing their jobs. That element is in the background of Watchmen, and the foreground of Fail-Safe, but it is present in both. In these stories, however, we also discover something besides the banality of evil, something different but equally disconcerting — the cruelty of good.

“Philanthropic people lose all sense of humanity,” Oscar Wilde observed. “It is their distinguishing characteristic.” Of all the characters in Watchmen, Ozymandias is the least connected to other people. Rorschach has his friendship with the Nite Owl, Dan Dreiberg. Dr. Manhattan loves — in his fashion — Laurie Juspeczyk. Even the Comedian shares a moment of tenderness with the Silk Spectre. (“[He] was gentle,” she says ” You know what gentleness means in a guy like that? Even a glimmer of it?”). And he tries, in his way, to connect with their daughter, experiencing a sense of dejected loneliness when that effort is cut short. The only people Ozymandias calls “friends” are in fact his servants — whom he murders with barely a twinge of guilt. He does seem momentarily regretful when he kills his pet lynx in a skirmish with Dr. Manhattan — but even that is soon eclipsed by his glee at destroying half of New York.

Undoubtedly, Veidt is an egotist and a megalomaniac, but the fuel for his self-conceit is, even more than his intelligence, his devotion to goodness — which is identical, he seems to believe, with his devotion to his own goodness. His altruism and his egotism are not in conflict, they are two sides of the same coin. Veidt’s motives, while self-righteous and even self-aggrandizing, are neither selfless nor selfish. Of all of the Watchmen, none of the others have motives so pure, and none of the others commit crimes of such magnitude. He sacrifices millions to his goodness, and it is his goodness, he believes, that gives him the right.

Bad Morality

Adolf Eichmann, Lieutenant Colonel of the Nazi SS, was likewise driven by a sense of — as he termed it — idealism. Arendt explained:

“An ‘idealist,’ according to Eichmann’s notions, was not merely a man who believed in an ‘idea’ or someone who did not steal or accept bribes, though these qualifications were indispensable. An ‘idealist’ was a man who lived for his idea . . . and who was prepared to sacrifice for his idea everything and, especially, everybody. . . . The perfect ‘idealist,’ like everybody else, had of course his personal feelings and emotions, but he would never permit them to interfere with his actions if they came into conflict with his ‘idea.'”

It was his sense of duty, as much as his dull careerist ambition, that kept Eichmann at his job, fastidiously arranging time-tables, making sure that enough cattle cars would be available to transport Jews to the death camps, and that enough Jews would be available to fill them.

Clearly something has gone wrong here, where the demands of duty drown out any sense of compassion, where one’s idealism comes at the cost of one’s humanity, and when conscience calls for murder. Eichmann was suffering from what the philosopher Jonathan Bennett has termed “bad morality.” Not merely as a Nazi, but as a citizen of the German Reich, Eichmann (wrongly) conflated the good with the law, and (correctly) identified the law with the Führer; and thus, anything that opposed the Führer’s will offended Eichmann’s sense of morality.

Arendt noted the astonishing fact of Eichmann’s conscience, but did not consider what this perversion of morality might tell us about morality itself. For Eichmann thought he was doing his duty, and the evil he enacted would not have been possible were it not for a value system that placed duty above all other considerations. In this sense, the SS officer was not mistaken when he described himself as a Kantian:

“[In] one respect Eichmann did indeed follow Kant’s precepts: a law is a law, there could be no exceptions. . . . This uncompromising attitude toward the performance of his murderous duties damned him in the eyes of the judges more than anything else. . . , but in his own eyes it was precisely what justified him. . . . No exceptions — this was the proof that he had always acted against his ‘inclinations,’ whether they were sentimental or inspired by interest, that he had always done his ‘duty.'”

As Arendt added later: “the sad and very uncomfortable truth of the matter probably was that it was not his fanaticism but his very conscience that prompted Eichmann to adopt his uncompromising attitude.”

Bennett, reflecting on the moral conscience of figures such as Heinrich Himmler, Jonathan Edwards, and Huck Finn, argues that it is best if our moral principles remain, to some degree, unsettled and revisable, that we alter them according to our experience, with special sensitivity to our emotional responses:

“[One] can live by principles and yet have ultimate control over their content. And one way such control can be exercised is by checking one’s principles in the light of one’s sympathies. . . . It can happen that a certain moral principle becomes untenable — meaning, literally that one cannot hold it any longer — because it conflicts intolerably with the pity or revulsion or whatever one feels when one sees what the principle leads to.”

I think that Bennett underestimates the problem his argument poses for morality, however. For morality, as it is typically understood, consists of a set of rules the very purpose of which is to supersede our inclinations.

If we revise our principles in light of our sympathies — as, I believe, Bennett is right that we must — then mightn’t we also revise them in light of our anger, our lust, our fear, or our greed? If we judge our principles by our emotional responses, are we to judge them by all of our emotional responses, or only those that we judge to be good? And how should we evaluate our emotions, except by reference to our principles?

Or perhaps, the entire question of principles is misplaced, of secondary rather than primary importance. Huck Finn resolved his personal dilemma — whether to turn in a runaway slave, when his (bad) morality said Yes and his human sympathy said No — by abandoning moral concerns altogether. Bennett observes: “Since the morality he is rejecting is narrow and cruel, and his sympathies are broad and kind, the results will be good.” Bennett then goes on:

“But moral principles are good to have, because they help to protect one from acting badly at moments when one’s sympathies happen to be in abeyance. On the highest possible estimate of the role one’s sympathies should have, one can still allow for principles as embodiments of one’s best feelings, one’s broadest and keenest sympathies.”

Here, it is not merely that sympathy may correct for erring principles. Sympathy is instead primary, and the principles are simply an effort to generalize about those characteristics that make us our best selves. Thus it may be better — and more reliable — to nurture “sympathies [that] are broad and kind” than to hold the correct principles, or to adhere to those principles one does hold. It is a subtle shift, but a crucial inversion: Virtue is not developed in the service of abstract principles; principles are developed as as abstractions from and supports for the virtues. The emphasis is not on questions of moral law, but on character. The resulting outlook is not strictly moral, but broadly ethical.

Sacrifices

Whether Ozymandias and the un-named Fail-Safe President suffered from their own bad moralities is an open question.

Ozymandias’ attack provides a test case for utilitarian reasoning. It follows from a system of thought in which the best results can justify any action. Conversely, the dilemma the other heroes face upon learning his secret presents a hard case for the Kantian: Is it better to let the world perish than to become complicit in a lie? “Will you expose me, undoing the peace millions died for?”

The Fail-Safe President, while pragmatically choosing the lesser of two great evils, reaches to the Bible for justifications. “Do you remember the story of Abraham in the Old Testament?” he asks General Black. “[K]eep the story of Abraham in mind for the next few hours. . . . I may be asking a great deal of you.” (In case there’s any question as to how far to push this allusion: the general’s first name is also Abraham, and the final chapter is titled “The Sacrifice of Abraham.”) Yet the point of the Biblical story (as Kierkegaard explained) was not that Abraham was right to sacrifice Isaac, but that Abraham stood outside of and above the universal, the ethical. He makes an exception of himself and, as such, he defies moral justification. The President of course does no such thing, and he never considers himself as anything more than an ordinary human being who happens to bear extraordinary responsibilities. He does not place himself above judgement, or beyond ethical categories. He and General Black, therefore, are tragic heroes but not knights of faith. They resemble less Abraham than Agamemnon, and New York — which is not spared — is not Isaac but Iphigenia.

Whatever the basis of action, the problem remains that doing the right thing will not always be a pleasant business. It may require sacrifices, and we may need a certain hardness of will to make them. That steadfastness can easily blur into a kind of cruelty, toward ourselves as well as others. Right action might thus carry an ethical cost. It may deform our character, especially when it becomes the central focus of a life, leading to complacency, self-righteousness, and an unyielding and even callous attitude to others. There is an additional sacrifice that one makes when one loses innocence to some moral purpose; but it requires a special kind of selfishness to preserve one’s own sense of goodness at the expense of another’s well-being.

Despite their similar actions, Ozymandias and the President appear as very different figures — suggesting, perhaps, that the content of their morality may be less at issue than their relationships to it. For the President, the crucial thing is that the war be averted; in the moment of crisis, the responsibility can only be a burden, and success is followed by guilt and grief. For Ozymandias, saving the world is his greatest challenge and his greatest triumph — and that is its cardinal significance. He wants to see the world saved, but he wants at least as badly to be the one who saves it. He willingly assumes that responsibility, and his victory is followed by joy, pride, satisfaction (and only later, doubt). Both men do what is right — at least, as far as possible, in their own judgment — but the President, unlike Veidt, does not feel that it makes him good. He has not, in other words, lost his sense of humanity, and when it comes to questions of character, that sense may be more important than mere morals.

[Editor’s Update: Ng Suat Tong has a response to this piece here.

Selected Bibliography

Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (New York: Penguin Books, 2006).

Jonathan Bennett, “The Conscience of Huckleberry Finn,” in Ethics, ed. Peter Singer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994).

Fail-Safe [film], dir. Sidney Lumet (Columbia Pictures, 1964; DVD, 2000).

Fail Safe [television movie], dir. Stephen A. Frears (Maysville Pictures, 2000).

Hannah Arendt [film], dir. Margarethe von Trotta (Heimatfilm, 2012).

Eugene Harvey and Burdick Wheeler, Fail-Safe (New York: HarperCollins, 1962).

Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling/Repetition, ed. and trans. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983).

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, Watchmen (New York: DC Comics, 1987).

Percy Bysshe Shelley, “Ozymandias,” in Poems, ed. Isabel Quigly (New York: Penguin Books, 1956).

A few weeks back I reposted an essay on superhero and fascism. Somewhat to my surprise, it generated more than 150 comments, mostly from folks skeptical about my thesis.

A few weeks back I reposted an essay on superhero and fascism. Somewhat to my surprise, it generated more than 150 comments, mostly from folks skeptical about my thesis.