Three Scenes

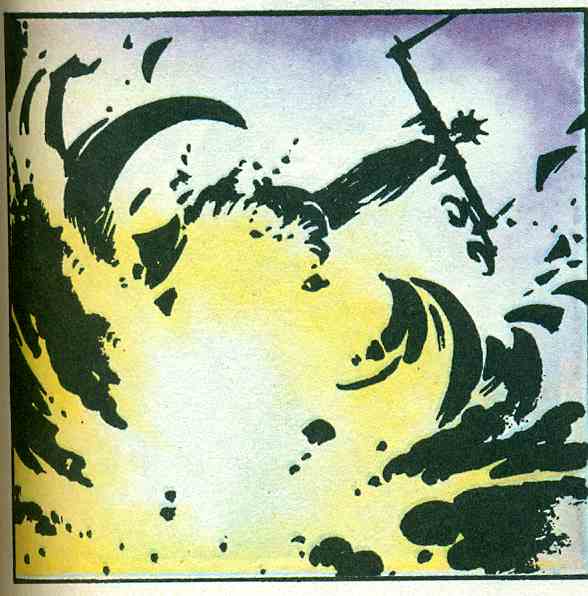

In the climactic scene of the Swedish film Män Som Hatar Kvinnor — literally, “Men Who Hate Women”; released in the U.S. as The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo[1] — the serial killer, Martin Vanger, fleeing from the heroine Lisbeth Salandar, runs off the road and flips his car. Injured and trapped, he pleads for his life as gas leaks from the tank: “I can’t… I can’t… I can’t move,” he cries piteously. “I can’t move. Help me. Please help me.” Lisbeth, however, can spare no feeling for the rapist and murderer who is suddenly at her mercy. She watches silently as the vehicle catches fire, and walks away while Vanger screams. We see the car explode behind her.

The image is distinctly reminiscent of another, filmed three decades before. In the final scene of 1979’s Mad Max, the cop — or ex-cop — Max Rockatansky finds himself similarly confronted with an enemy at his mercy. Here, too, a vehicle is overturned, leaking gas, and the villain pleads with the hero: “Don’t bring this on me, man. Don’t do this to me, please.” And here, too, the hero is unmoved. Max, in fact, takes a more active role that Lisbeth. He handcuffs the “Johnny the Boy” to the overturned truck, fashions an ad hoc fuse where the gas is leaking, and hands him a hacksaw, saying: “The chain in those handcuffs is high-tensile steel. It will take you ten minutes to hack through it with this. Now, if you’re lucky, you can hack through your ankle in five minutes.” As Max drives away, we see the explosion in the background.

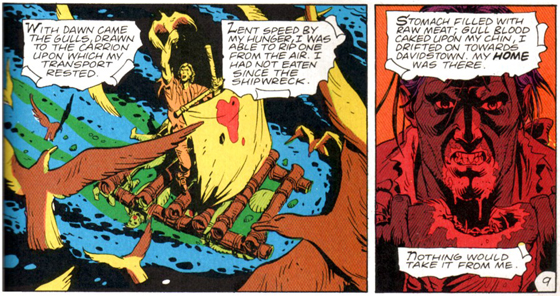

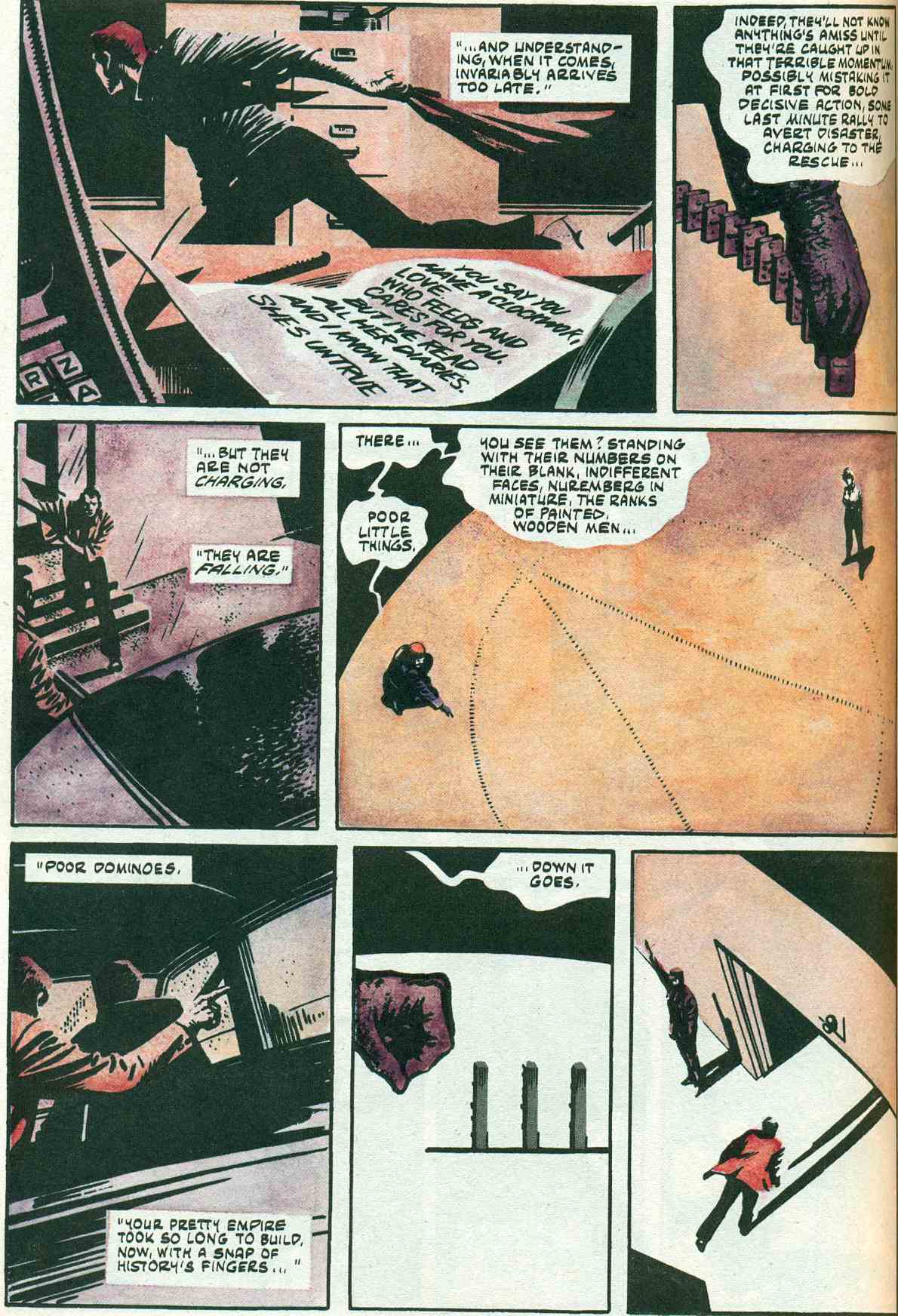

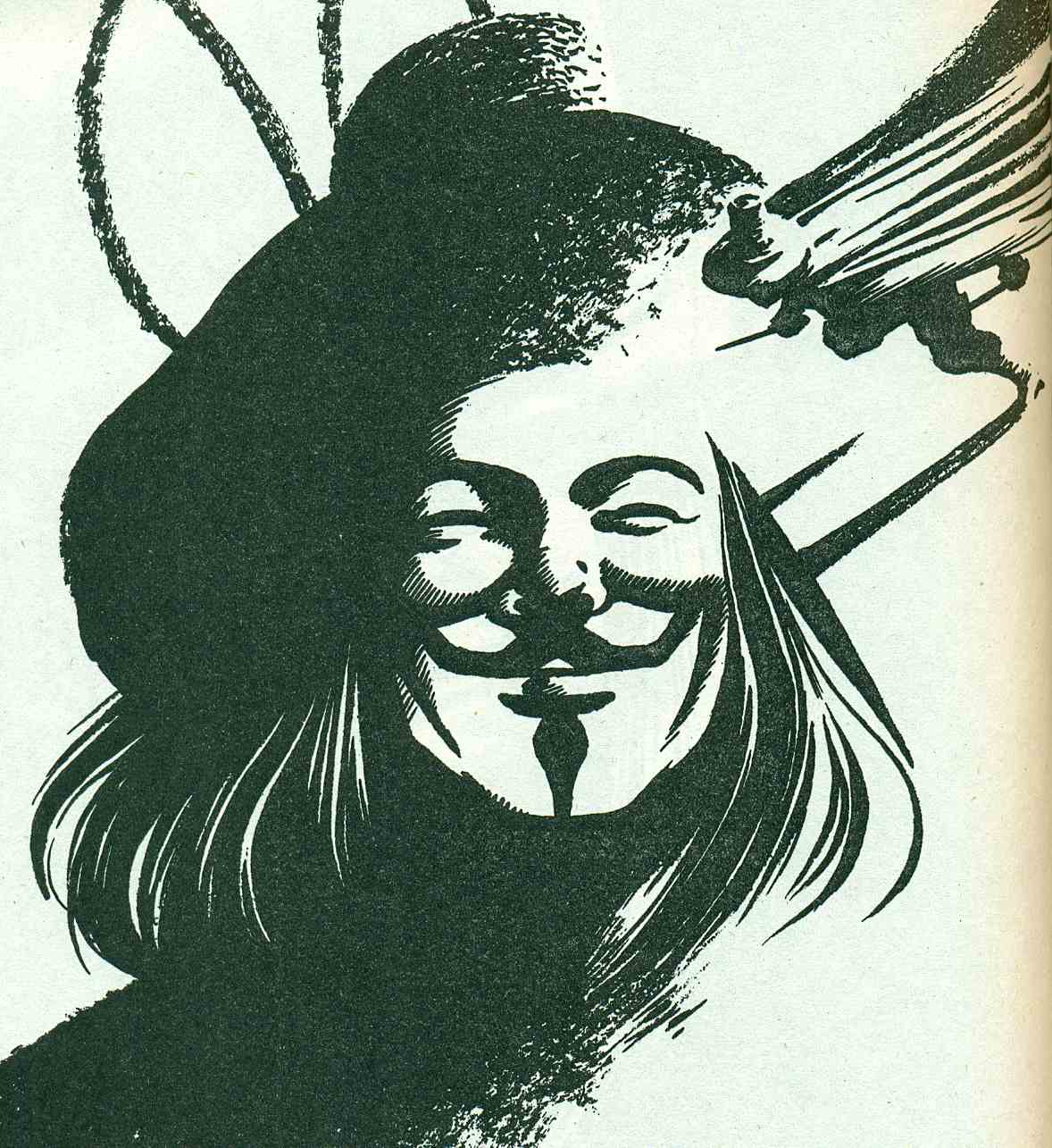

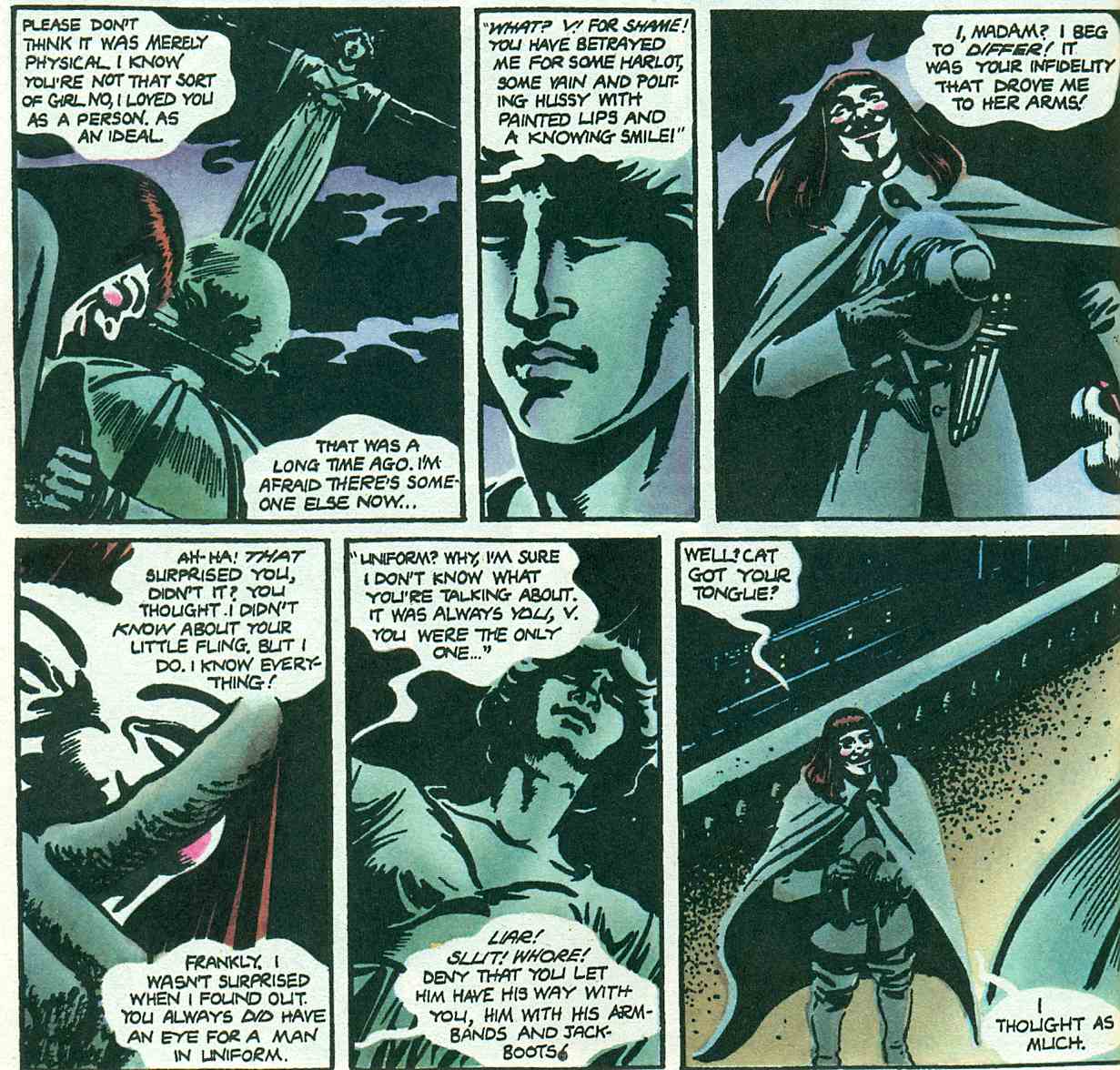

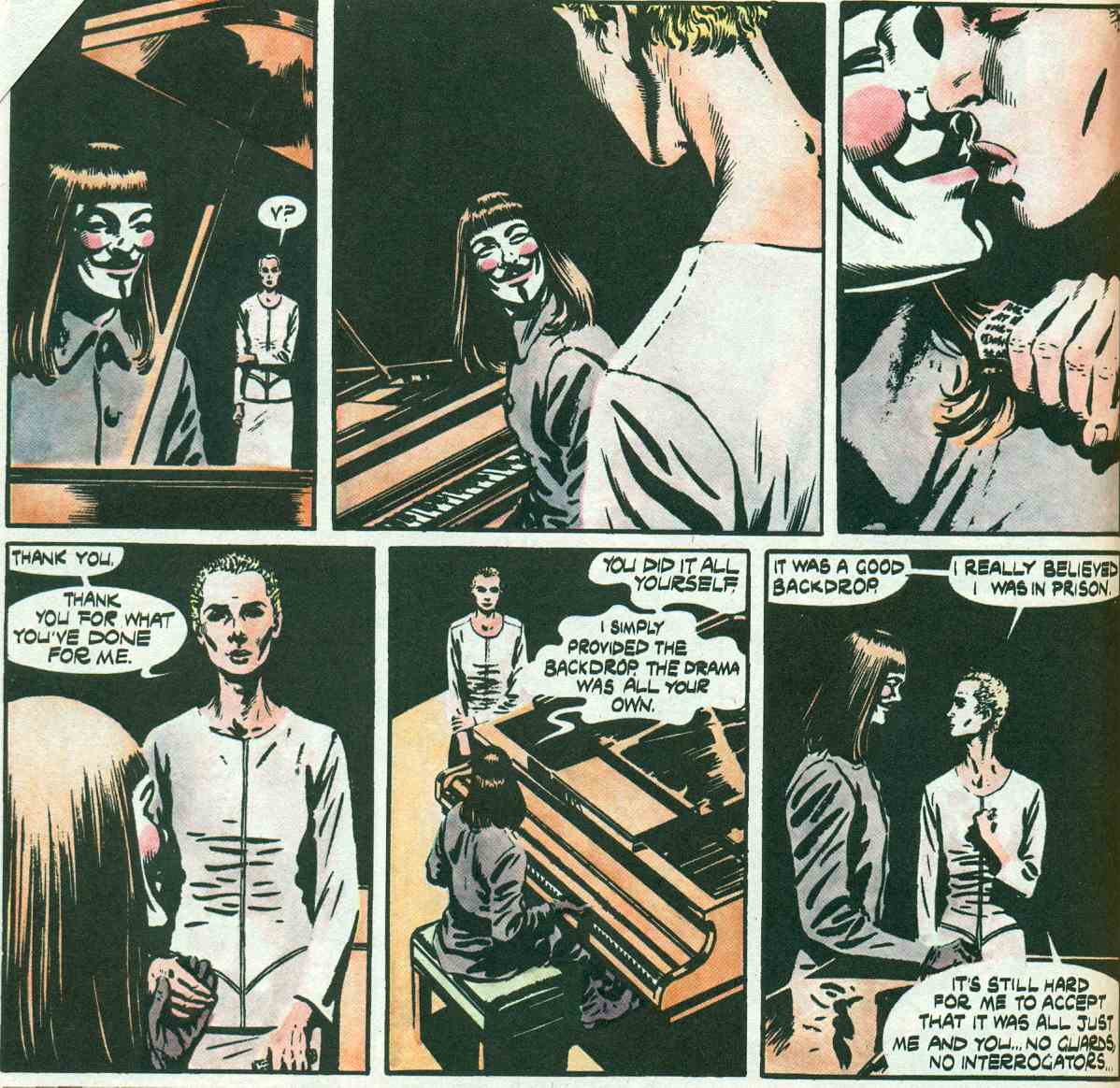

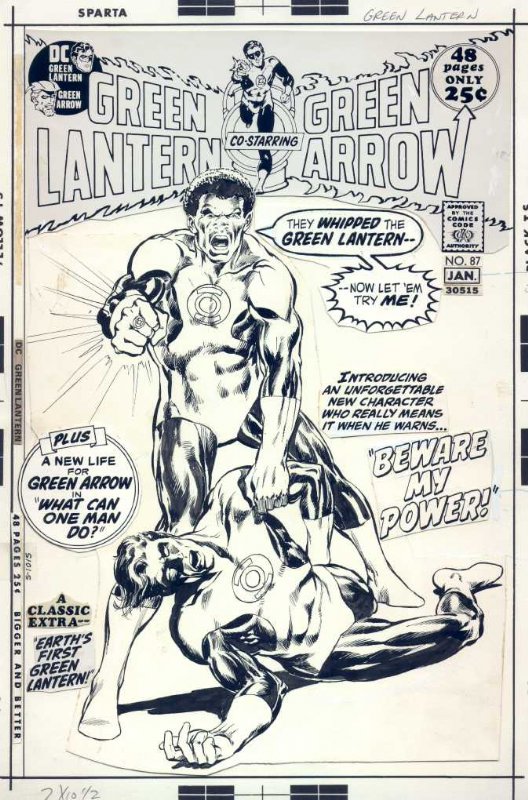

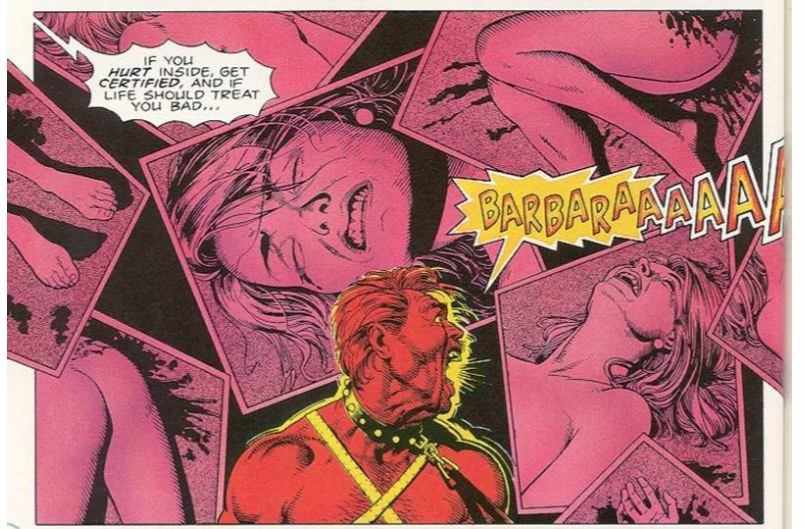

The hacksaw shows up again a few years later in Alan Moore’s graphic novel, Watchmen.[2] In the sixth chapter, Walter Kovacs recounts how he became the masked avenger Rorschach: “1975. Kidnap case. Perhaps you remember. Blaire Roche. Six years old. . . . Thought of little child, abused, frightened. Didn’t like it. Personal reasons. Decided to intervene. Promised parents I’d return her unharmed.” He does, eventually, find the girl — or rather, her remains. Then Rorschach waits, hiding, for the killer to return home. When he does, Rorschach handcuffs him to an old stove, leaves him with a saw, and sets the building on fire. Unlike Lisbeth or Max, Rorschach stays to face what he has done: “Stood in street. Watched it burn. . . . Watched for an hour. Nobody got out.”

The Moment of Truth

In each of these stories, the incident with the fire — triumphant and horrifying — is treated as a revelation. It shows us what kind of person the hero really is.

Yet in all three stories, the hero had already been portrayed as ruthless and vengeful. Lisbeth had previously tortured and then blackmailed a rapist. Max had hunted down and killed other members of a murderous motorcycle gang, sometimes using torture to do so. And Rorschach’s methods are so extreme they even frighten other superheroes. But to kill a person who is helpless is presented as an ultimate transgression, a final forbidden threshold, a border at the outer limits of moral goodness.

All three heroes kill their helpless adversaries, if only by their inaction, but the event signifies different things for each of them. For Rorschach it is a transformation: When he sees that the kidnapper had killed the girl and fed her to his dogs, he recalls, “It was Kovacs who closed his eyes. It was Rorschach who opened them again.” For Max the crisis is the culmination of a process long underway: He had previously worried that “any longer out on that road, and I’m one of them. . . a terminal crazy.” By the end he has lost everything to the forces of barbarism — his friend, his family, his sense of his own goodness — and he does, finally, become a barbarian himself. The representative of law becomes an outlaw.

For Lisbeth, however, the revelation is different. As she watches Vanger burn, she flashes back to a scene of a child deliberately throwing gas on a middle-aged man, and setting him ablaze. In the second film of the series, The Girl Who Played with Fire, we learn that she was the girl; the man, her father; and she was acting to save her mother from his persistent abuse. Lisbeth was institutionalized as a result. Thus her character is revealed at the climax, but with reference to a transformation that occurred much earlier. And yet the two scenes are identified: she is, in some ways, still that little girl. And, watching Vanger burn, it is as though she is not only remembering, but re-living the first attack. In that sense, by the film’s identification of these acts, we again see the heroic transgression as both revelatory and transformative.

It is interesting to compare Lisbeth’s back-story and Rorschach’s. Walter Kovacs, too, saw his mother mistreated by men, and was himself “regularly beaten and exposed to the worst excesses of a prostitutes (sic) lifestyle.” The critic Katherine Wirick has persuasively pointed to textual evidence that he was sexually abused as well.[3] Then in one scene, Kovacs — just a little boy — attacks some older children who are threatening him. Fire is the weapon here, too: he burns one of the bullies, blinding him with a cigarette. After that he is institutionalized.

But Rorschach’s transformation comes later, like Max’s. And in both stories, the critical moment when they put themselves beyond the law comes as a kind of revelation, not only about them, but for them. Max has learned how fragile civilization really is, how easily chaos overtakes order. Rorschach, likewise, opens his eyes. As he watched the kidnapper’s house burn, he

looked at sky through smoke heavy with human fat and God was not there. The cold, suffocating dark goes on forever, and we are alone. . . . Existence is random. Has no pattern save what we imagine after staring at it for too long. No meaning save what we choose to impose. . . . . Was reborn then, free to scrawl own design on this morally blank world.

Lisbeth, however, experiences the climactic scene not as a revelation, but as a return to painful memories. She has known for a long time the kind of world she is living in.

So Max abandons civilization for the wasteland, and Rorschach uses violence to impose order where none exists — but Lisbeth’s rejection of order takes the form of resistance. Martin Vanger is not merely a rapist and serial murderer. He is also wealthy and powerful, from a prominent family with a Nazi past. In the context of the story, he is a representative of the social order, and especially its worst aspects — corporate control, lingering fascism, racism, and male dominance. And Lisbeth’s father, too, (we learn in the sequels) is not only a misogynist and a bully, but a human trafficker operating with the protection of ta secret section of the intelligence services. It is not chaos, but the forces of order, that Lisbeth fears; and when she attacks her father, and later, when she lets Vanger die, she does so to protect the people she loves.

Redemption Without Forgiveness

Mad Max ends with Max driving into the desert, the explosion behind him, his transformation from law to lawlessness complete. But the movie’s sequel, The Road Warrior, tells the story of his redemption. After months, or possibly years, surviving as a kind of scavenger, Max helps to defend a small community against a horde of bandits and regains some of his humanity in the process. It is a story of redemption, but redemption without forgiveness: The people he has helped to save leave him stranded on the roadway, in the desert, alone. The future he has fought for, and the community he defended, have no place for him.

Rorschach’s redemption is equally ambivalent. He alone, among all the superheroes, cannot be blackmailed into silence after discovering that one of their own has attacked New York, killing millions but likely averting nuclear war. Ozymandias asks, “Will you expose me, undoing the peace millions died for? Kill me, risking subsequent investigation? Morally, you’re in checkmate.”

Dr. Manhattan, the Silk Specter, and the Nite Owl, all quickly acquiesce: “Exposing this plot, we destroy any chance of peace, dooming earth to worse destruction”; “We’re damned if we stay quiet, Earth’s damned if we don’t.” They soon agree to “say nothing.”

To which Rorschach replies: “Joking, of course.” He then interrupts further argument: “No. Not even in the face of Armageddon. Never compromise.”

Rorschach’s unwavering position is just what we should have expected — not because he believes in moral absolutes, exactly, but because he believes that we alone are responsible for the world we live in. As he watched the fire that fatal night, years before, Rorschach realized, “This rudderless world is not shaped by vague metaphysical forces. It is not God who kills the children. Not fate that butchers them or destiny that feeds them to the dogs. It’s us. Only us.” Later, in his last entry in his journal, he wrote: “For my own part, regret nothing. Have lived life, free from compromise . . . and step into the shadow now without complaint.” The only thing that Rorschach can be certain of is his own integrity, and so that becomes his absolute. He is unbending in his own moral code precisely because he has seen that there are no absolutes.

The other heroes, equally naturally, cannot allow him to reveal what he knows. The only way to stop him is to kill him, and Rorschach accepts this martyrdom. But it is significant, I think, that at the end he takes off his mask. Facing death, he becomes, once again, Walter Kovacks. In death, Rorschach rejoins humanity.[4]

Lisbeth Salandar fares better. She walks away from the burning car and returns to Mikael Blomkvist, her investigative partner and occasional lover. Later, he asks her:

“What happened out there? He didn’t die in an accident, did he? …”

“He burned to death.”

“Could you have saved him?”

“Yes.”

“But you let him burn.”

“Yes.”

Mikael thinks for a long moment, and lies down, exhausted. Lisbeth lies next to him. Struggling to speak, he says: “I would never have done that, Lisbeth. But I understand why you did it. I don’t know what you’ve been through. . . . Whatever it is you’ve been through — you don’t have to tell me. I’m just glad you’re here.”

“Thanks,” she says, and takes his hand.

Mikael’s reaction is complex. He neither idealizes nor judges. He does not justify her action, or forgive it. He wants only to understand, though he will not demand that she explain herself. It is a moment of deep compassion. Sympathetic understanding is a reaction not usually associated with heroism, but one most appropriate to tragedy.

Heroic Sacrifice

Understanding is not without its risks. The title of Watchmen’s sixth chapter, “The Abyss Gazes Also,” is taken from a quote of Nietzsche’s: “Battle not with monsters, lest ye become a monster, and if you gaze into the abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.” In the story this epigram refers, first, to Rorschach’s nihilistic epiphany and the change in character that overtakes him, and then, to the attempts of a prison psychologist to comprehend the workings of Rorschach’s mind. But the warning might apply to the reader as well: Our heroic fictions sometimes contain dangerous truths.

It is possible to read these stories — Mad Max, Watchmen, and The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo — as revealing, not only the nature of these heroes, but the dark side of our heroic ideals. (That is, after all, the entire point of Watchmen.) The transformation of victim into avenger is central to revenge stories, of course, but in each of these three cases that transformation is also treated as a kind of loss. There may be some symbolism in the fact that both Rorschach and Max offer their victims an improbable and cruel chance for escape. Are they suggesting, from their own experiences, that the price of survival is severing a part of oneself?

The heroic figure is defined, in large part, by the risks he accepts and the sacrifices he makes. What these stories show is that, among the things he may risk — and sacrifice, if need be — is not merely his life, but his own moral standing. This risk, this sacrifice, cannot be understood only in terms of particular actions, but more broadly as such actions help to shape one’s character. At the end of the ordeal, a hero may well be a worse person.[5] We often hear of the heroic virtues — qualities such as courage, loyalty, and resilience — but less is said of the heroic vices. Prolonged exposure to violence may well leave one bitter, vengeful, suspicious, cruel, callous, even cynical and sadistic. In the revenge fantasy, it is precisely these attributes that motivate the heroic transgression.

Our heroes — Max, Rorschach, Lisbeth — are not just imperfect, they are deeply damaged. And their actions seem to occupy a space outside of our normal moral judgments. The deaths they cause cannot rightly be called justice, but neither are they merely murder. And these killers, whom we may love or admire, are not simply Good Guys, and are not quite villains. In this sense they might be thought of as monstrous. The evil they do is the result of their virtues, and the good that they do depends upon their vices. These two elements cannot be separated, they cannot be reconciled, and they do not cancel each other out. The heroic ideal subsumes, or surpasses, our moral categories; the heroic figure, however, is sometimes destroyed by the contradiction. Hence, the sense of tragedy. Hence, also, the need for redemption — to enter, again, into the moral community, to regain some measure of humanity.

[1] I’m writing specifically of the first film. The American film, and the original novel, on which the films were based, handle this scene quite differently.

[2] Here, I’m specifically discussing the comic. The saw is absent from the film version.

[3] Katherine Wirick, “Heroic Proportions,” The Hooded Utilitarian, April 5, 2012.

[4] This reading gives a double meaning to Dr. Manhattan’s earlier prediction: “I am standing in deep snow. . . I am killing someone. Their identity is uncertain.”

[5] It is interesting how commonly philosophers have forgotten about the effects on one’s character as a relevant moral consideration. Thomas Nagel, for example, has written: “the notion that on might sacrifice one’s moral integrity justifiably, in the service of a sufficiently worthy end, is an incoherent notion. For if one were justified in making such a sacrifice. . . then one would not be sacrificing one’s moral integrity by adopting that course: one would be preserving it.” Thomas Nagel, “War and Massacre,” in Mortal Questions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980) 63. Notice that Nagel assumes that the person who embarks on the sacrifice and the one who remains when the sacrifice is over are substantially the same. One may tell a lie for decent and even justifiable reasons. If those reasons force one to lie repeatedly over a long enough period, however, it seems at least possible that one will lose the habit of truthfulness, and his estimation of its value may well decline. The notion that one’s integrity is preserved not only during such a shift in values, but through it, would seem to rob the notion of integrity of any content.