Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen is certainly no stranger to “best of” lists. In 2008, Entertainment Weekly looked across the entire landscape of book publishing—fiction and non-fiction, prose efforts and comics works—and put together a ranked list of the “100 Best Reads from 1983 to 2008.” (Click here.) Watchmen was listed at #13, which included it among the top ten works of fiction of the period. And a few years earlier, in 2005, Time magazine included Watchmen in its list of the 100 best English-language novels between 1923 and 2005. (Click here.) Time is an establishment publication, and it is certainly not prone to any radical pronouncement. The magazine put Watchmen in the company of such classics as The Great Gatsby, To the Lighthouse, and The Sound and the Fury. The book’s more contemporary peers included Beloved, American Pastoral, and Never Let Me Go. No other comics work was given this distinction.

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen is certainly no stranger to “best of” lists. In 2008, Entertainment Weekly looked across the entire landscape of book publishing—fiction and non-fiction, prose efforts and comics works—and put together a ranked list of the “100 Best Reads from 1983 to 2008.” (Click here.) Watchmen was listed at #13, which included it among the top ten works of fiction of the period. And a few years earlier, in 2005, Time magazine included Watchmen in its list of the 100 best English-language novels between 1923 and 2005. (Click here.) Time is an establishment publication, and it is certainly not prone to any radical pronouncement. The magazine put Watchmen in the company of such classics as The Great Gatsby, To the Lighthouse, and The Sound and the Fury. The book’s more contemporary peers included Beloved, American Pastoral, and Never Let Me Go. No other comics work was given this distinction.

When one reads Watchmen, whatever skepticism one has about such acclaim quickly falls away. It is a superb work that triumphs on multiple levels. Watchmen is simultaneously a first-rate adventure story, an incisive analysis of the superhero genre, and a brilliant meditation on how one’s sense of reality is defined by one’s perspective—knowledge and ignorance, hopes and fears, predispositions and agendas.

The book’s starting point is a mystery plot. The Comedian, a former costumed hero and now a covert government operative, is brutally murdered. It gradually becomes clear his murder is part of a larger conspiracy. Dr. Manhattan, the only one of the heroes with superpowers—and he is nearly omnipotent—is driven away from society by an elaborate smear. Rorschach, the last of the heroes to operate without government sanction, is framed for murder, captured, and imprisoned. Ozymandias, who retired from adventuring years earlier, foils a gunman’s attempt on his life. Someone is out to eliminate the heroes, but who, and why?

The answer turns out to be horribly ironic, with the reasons a black joke on the puny, naively idealistic desire to make a better world by putting on a costume and beating up criminals. The conspiracy to eliminate the costumed heroes is revealed as a tangent in a greater plot that changes the world. Along the way, Moore and Gibbons treat the reader to one terrific suspense setpiece after another. And in marked contrast to Zack Snyder, the director of the horrid film adaptation, they understand that violence is made all the more effective by restraint.

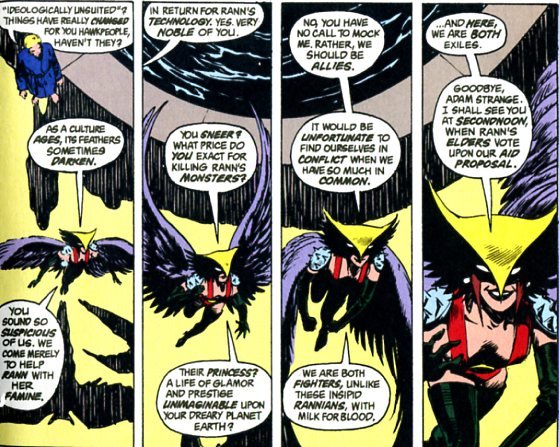

One of the most common observations about Watchmen is that it is both a superhero adventure story and a critique of the genre. In the appreciation of the book he sent with his top-ten list, Francis DiMenno identifies this with critic Harold Bloom’s theory of the “anxiety of influence.” In DiMenno’s view, Alan Moore, the book’s scriptwriter and acknowledged mastermind, has such a relationship with the superhero genre. One can see his point, but I’m more inclined to identify Watchmen’s anxiety of influence with Harvey Kurtzman’s “Superduperman” and other superhero parodies in MAD. The theory argues that a younger artist feels belated relative to older ones whose work is admired. The only way to compete with the older work—and assert one’s own artistic identity—is to beat the earlier artist at his or her own game, which is accomplished by changing the rules. In works like “Superduperman,” Harvey Kurtzman exposed the fallacies of the genre with derision and exaggeration. In contrast, Moore, who acknowledges a large debt to Kurtzman, examines his own superhero characters with the acute eye of a first-rate prose novelist. He doesn’t mock them; he plays things entirely straight, and he presents the fanciful characters in as ruthlessly realistic a manner as possible. He reveals the grotesquely maladjusted attitudes that motivate the various superheroes, turning them into figures of pathos and horror. Rorschach, Dr. Manhattan, and the others are among the most memorable characters in contemporary fiction.

One of the most common observations about Watchmen is that it is both a superhero adventure story and a critique of the genre. In the appreciation of the book he sent with his top-ten list, Francis DiMenno identifies this with critic Harold Bloom’s theory of the “anxiety of influence.” In DiMenno’s view, Alan Moore, the book’s scriptwriter and acknowledged mastermind, has such a relationship with the superhero genre. One can see his point, but I’m more inclined to identify Watchmen’s anxiety of influence with Harvey Kurtzman’s “Superduperman” and other superhero parodies in MAD. The theory argues that a younger artist feels belated relative to older ones whose work is admired. The only way to compete with the older work—and assert one’s own artistic identity—is to beat the earlier artist at his or her own game, which is accomplished by changing the rules. In works like “Superduperman,” Harvey Kurtzman exposed the fallacies of the genre with derision and exaggeration. In contrast, Moore, who acknowledges a large debt to Kurtzman, examines his own superhero characters with the acute eye of a first-rate prose novelist. He doesn’t mock them; he plays things entirely straight, and he presents the fanciful characters in as ruthlessly realistic a manner as possible. He reveals the grotesquely maladjusted attitudes that motivate the various superheroes, turning them into figures of pathos and horror. Rorschach, Dr. Manhattan, and the others are among the most memorable characters in contemporary fiction.

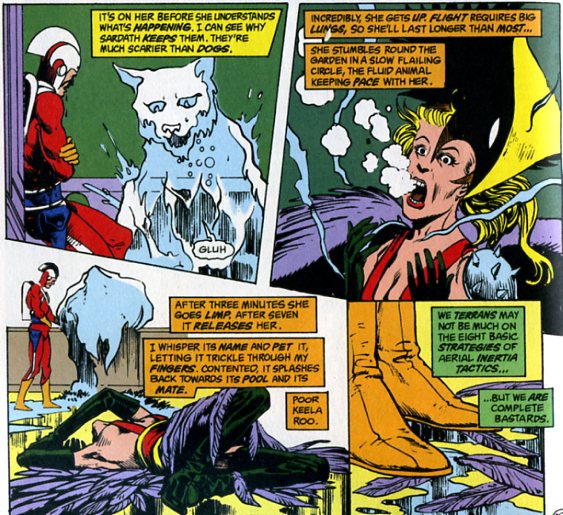

Watchmen is an extraordinarily compelling read, but what makes it an extraordinarily compelling reread is its meditation on perspective and how it shapes one’s understanding. On its most profound level, the book is about interpretation and the act of reading itself. The work’s defining metaphor is the Rorschach blot—a psychiatric tool for teasing out a person’s attitudes and preoccupations. One is asked to look at a blob of ink and elaborate the associations and thoughts one projects onto it. One sees permutations of this throughout the book, such as when Dr. Manhattan, Ozymandias, and a third hero, Nite Owl, attend the Comedian’s funeral. They think back on him during the service, and it’s clear none had any significant relationship with him; they only see him as a metonymy for their own anxieties. Moore and Gibbons also dramatize the most extreme perspectives; in one chapter we are shown experience through the eyes of a psychopath, and in other we see things through the eyes of eternity, and understand what it can mean to be aware of all times at once. The book almost always presents knowledge as incomplete. And when it is complete, it is skewed by other factors, so people fail to reach the correct conclusions. In one of the book’s subplots, the main female character knows everything necessary to recognize a certain man is her real father, but her dysfunctional relationship with her mother so distorts her view that she can’t see it. And misunderstandings not only affect one’s personal life, they direct the tide of history. At the end of the book, the world has changed because everyone misinterprets a catastrophe. Will they accept the truth once they are told it? The book ends on that question, and one is inclined to answer no.

Watchmen is an extraordinarily compelling read, but what makes it an extraordinarily compelling reread is its meditation on perspective and how it shapes one’s understanding. On its most profound level, the book is about interpretation and the act of reading itself. The work’s defining metaphor is the Rorschach blot—a psychiatric tool for teasing out a person’s attitudes and preoccupations. One is asked to look at a blob of ink and elaborate the associations and thoughts one projects onto it. One sees permutations of this throughout the book, such as when Dr. Manhattan, Ozymandias, and a third hero, Nite Owl, attend the Comedian’s funeral. They think back on him during the service, and it’s clear none had any significant relationship with him; they only see him as a metonymy for their own anxieties. Moore and Gibbons also dramatize the most extreme perspectives; in one chapter we are shown experience through the eyes of a psychopath, and in other we see things through the eyes of eternity, and understand what it can mean to be aware of all times at once. The book almost always presents knowledge as incomplete. And when it is complete, it is skewed by other factors, so people fail to reach the correct conclusions. In one of the book’s subplots, the main female character knows everything necessary to recognize a certain man is her real father, but her dysfunctional relationship with her mother so distorts her view that she can’t see it. And misunderstandings not only affect one’s personal life, they direct the tide of history. At the end of the book, the world has changed because everyone misinterprets a catastrophe. Will they accept the truth once they are told it? The book ends on that question, and one is inclined to answer no.

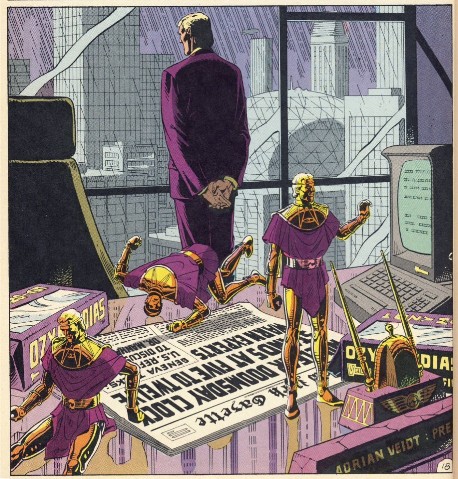

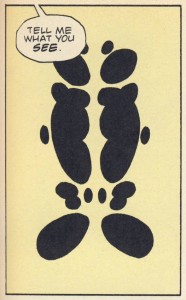

Moore and Gibbons extend their treatment of interpretation and misinterpretation to the reader’s experience of the book. If one has read Watchmen before, go back and reread the first chapter. Details that seemed extraneous the first time around jump out at one. Others, such as the recurring image of the spattered smiley face, recede into the background. Dialogues take on a different meaning, such as the conversation between the two detectives in the opening scene. Is one sincere when he says a certain crime was probably random and not worth much investigation? Or consider this panel:

How was this image interpreted—i.e. what meaning was projected onto it—the first time around? Was the emotional resonance from an earlier scene with the Nite Owl character brought over to it? Did one see it as a pensive moment of doubt on Ozymandias’ part about how he has spent his life? Were the dolls in the foreground seen as a trope for this doubt? And how is it interpreted on the second reading, with knowledge of the entire book? Does one now see Ozymandias contemplating an unexpected problem, with the toys a trope for his distraction? This panel, like all of them, is a Rorschach blot for the reader; one sees what one projects onto it. The differing interpretations also bring to mind a quote Alan Moore was fond of in a later work, “Everything must be considered with its context, words, or facts.”

Illustrator Dave Gibbons does a magnificent job of realizing his collaborator’s vision. Moore may be the mind behind Watchmen, but Gibbons is its extraordinarily deft hands. He was a seasoned adventure cartoonist when he began the project, and one sees his assurance in every panel. He handles the quiet scenes as effectively as the violent ones. There’s also an understated, almost laconic quality to his dramatization of the characters. He shows the reader what is happening; one is never told what to think about it. And the remarkable literalness of his style—clear compositions, fully realized deep-space perspectives, copious detail—is perfect for a work that at its core is about the unreliability of perception. Gibbons shows the reader everything, and it remains ambiguous anyway.

I could go on and on about the book. It does what the most impressive ones do; it makes you want to talk about its achievements forever. That’s why it deserves to be considered one of the finest novels of our era. Not to mention one of the best comics.

Robert Stanley Martin is the organizer and editor of the International Best Comics Poll. He writes for his own website, Pol Culture, and is a contributing writer to The Hooded Utilitarian. He has previously written on comics for the Detroit Metro Times and The Comics Journal.

NOTES

Watchmen, by Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons, received 31 votes.

The poll participants who included it in their top ten are: J.T. Barbarese, Piet Beerends, Eric Berlatsky, Noah Berlatsky, Alex Boney, Scott Chantler, Tom Crippen, Marco D’Angelo, Francis DiMenno, Anja Flower, Jason Green, Patrick Grzanka, Paul Gulacy, Alex Hoffman, Mike Hunter, John MacLeod, Scott Marshall, Robert Stanley Martin, Todd Munson, Jim Ottaviani, Marco Pellitteri, Michael Pemberton, Charles Reece, Giorgio Salati, M. Sauter, Matthew J. Smith, Nick Sousanis, Joshua Ray Stephens, Ty Templeton, Matt Thorn, and Qiana J. Whitted.

Watchmen was originally published as a 12-issue serial in comic-book pamphlet form in 1986 and 1987. The serial was collected and published as a graphic novel in 1987, and has been a mainstay of book retailers ever since. It should also be available at most public libraries.

–Robert Stanley Martin