In a comment to my post from last week, R. Maheras wrote:

“I was at SPX today, and almost every complaint about homogenized superhero comics can probably be made about contemporary small press.

There’s a relative sameness pervading contemporary small press that I don’t remember seeing during the small press explosion of the 1980s.

Zombies, cutesy creatures/monsters, or reality-based angst comics seemed to be bulk of what’s available these days.

In the 1980s, I was snapping up dozens of small press comics every month. At SPX, While I spent about $120, I was hard-pressed to find stuff I wanted to sample. One of the more interesting things I found was actually what creator Pat Barrett himself only half-jokingly labeled a screed: “How to Make Comics the Whiner’s Way.” I thought it was actually a pretty good indictment of what appears to be a substantial faction of today’s small-pressers.”

I was also at SPX this weekend. This comment made me want to use my words and Noah was kind enough to put this up as a separate post instead of hiding it in the comments.

I’ve been going to SPX since 2002 – a few years covering the show for a small local magazine here in the DC area, then one year as a volunteer, and this was my sixth year selling my own comics as the man in the purple suit. (Full disclosure: I also maintain the SPX Good Eats Google Map.)

Over the course of the past decade, my wife and I have come up with a game at SPX. She goes off and finds stuff and I go off and find stuff. When we compare our finds, we ask each other “where did you get that?” It’s very obvious that what she finds interesting in comics is very different than what I find interesting in comics and we always spot very different things at the show, so much so that it’s almost like we’re at completely different shows. I tend to regard that as a feature, not a bug.

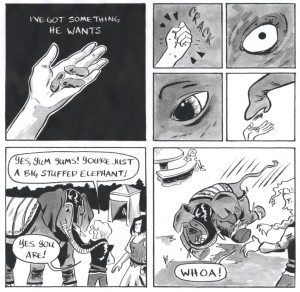

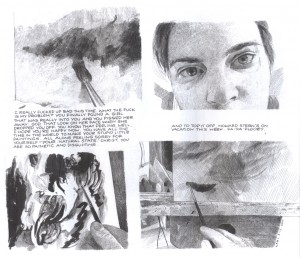

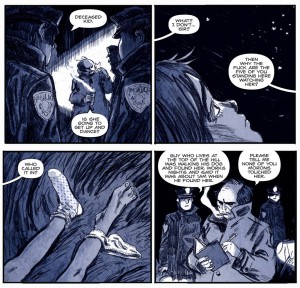

My wife picked up Pat Barrett’s book for me and she talked to him about it. He told her that it was written in response to people who knew they wanted to make comics but didn’t know what they wanted to create. Mind you, that’s hearsay so it’s impossible to say exactly what his intention was (and I argue that we should look at the primary source instead of the author’s intent anyway). Having read the book last night, I saw a very pointed sendup of “How-To” books, especially those that are aimed at teaching people how to draw. And yes, there was a lot snark aimed at autobiographical comics, which were all the vogue a few years ago.

One of the interesting things about comics these days is the conventional wisdom that if a comic isn’t about superheroes then it’s pretty much automatically not commercially viable. And that lack of concern about whether or not a book is going to sell has opened the floodgates to allow just about every kind of comic under the sun – both in terms of subject matter available, art style and format. And, as far as I’m concerned, the best thing about indie comics is the almost complete lack of homogenization or sameness on offer.

For example, on my row of tables (I was on what Rafer Roberts called “the fifty yard line” of the room) there were Warren Craghead and Simon Moreton’s minimalist comics, a gay porn space opera, my eclectic collection of books, video game inspired books, and a guy selling bad caricatures and an apology for a dollar. There was also a wide range of books available from the DC Conspiracy, Interrobang Studios, Nix Comics and the Spider Forest Webcomics Collective.

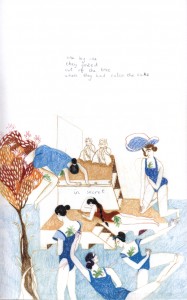

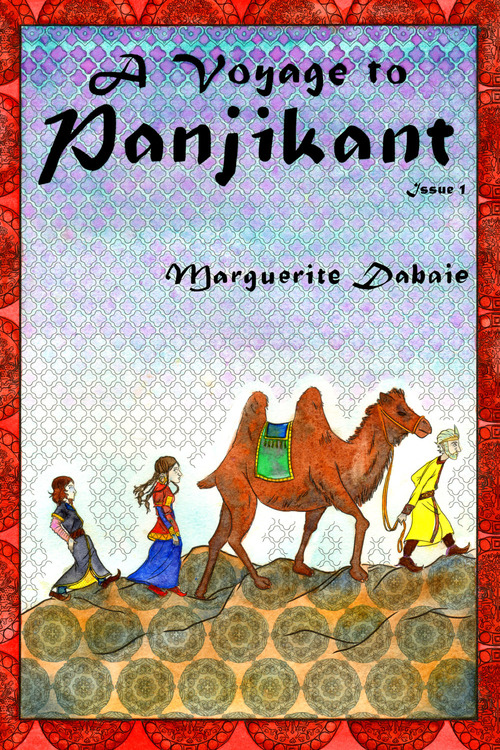

My must-buy book of the show this year was my friend Marguerite Debaie’s A Voyage to Panjikant, a meticulously researched historical fiction about traders living on the Silk Road in the Seventh Century. It’s a beautiful book that’s colored entirely in watercolor. I also picked up a space opera comic called Galaxion by Tara Tallan, simply because it looked interesting. I even went out of my way to pick up the few books from Frank Santoro’s Comics Workbook competition that were at the show – Jared Cullum’s Baba’s Accordion, Alexey Sokolin’s Freefall, and Alexander Rothman’s Vespers.

Not a one of these are “[z]ombies, cutesy creatures/monsters, or reality-based angst comics,” but it’s easy to understand why it seems like that’s what the room had to offer. With such a large variety of material to choose from, it was impossible for any single individual to wrap their arms around everything that was available. I think a certain amount of confirmation bias does tend to creep into what people tend to see at shows like this when the options are so overwhelming. We see what we expect to see because there is no way to really carefully evaluate everything.

I saw volumes of Shakespeare that contained beautiful handcut paper illustrations. I saw a comic printed on a strip of canvas. I saw comics that were printed at mini comic size, traditional comics size, magazine size, square format, horizontal format, and were massively oversized. I saw comics that were photocopied and hand-stapled. I saw mass-printed books with beautiful production values. I saw parody books that were waiting patiently for cease-and-desist letters and wonderful original concepts.

And yes, I did see some zombie books because zombies are big in pop culture right now. I saw autobiographical comics because most first novels are bildungsromans and it shouldn’t surprise anyone that comics follow the same patterns as novels. And there is always a great deal of cutesy stuff on display because the one thing that always sells at a show of such magnitude is a quick, easy hook that makes you laugh and only costs a few bucks.

And yes, you could make some of the same complaints about the books available at SPX that can be made about superhero comics – some are poorly drawn, some are poorly written and some are not well thought out at all.

But you cannot complain that indie comics have crippling continuity issues that prevent newcomers from picking them up. You cannot complain that indie comics present a straight white male view of the world that is not friendly to women and minorities (in fact, there was a greater preponderance of books with the word “feminist” in the title this year than there has been in years past). You cannot complain that indie comics are dominated by white males (the creator split was about 50/50 gender-wise, not so much racially). You cannot complain that indie comics are mired in endless editor-driven events that force you to buy a dozen books to get the full story. You cannot complain that indie comics have devolved into corporate IP farms whose stewards are more interested in maintaining the long-term viability of characters than they are in character development.

The real joy of attending a show like SPX is that everyone in the room is there because they want to be – because they are desperately, passionately in love with the medium and the possibilities inherent in comics. And yes, the creators would really like to make money. But most of them know that they will probably not break even, but for some weird reason they show up anyway.

Given that half of the people exhibiting at SPX this year were there for their first time, it’s entirely possible that a good portion of them went for the easy options and chose the same basic topics that most newbies choose. But if that’s all you saw then you were not looking very hard because there was a lot of weird, crazy, interesting, creative, exciting stuff available. I had to stop browsing because I went over budget twice – and I intentionally avoided the big publisher tables. I’d even go so far as to say that there was a book in the room for just about anyone from any walk of life. And that’s absolutely not something that you can say about mainstream superhero comics.