I sort of felt like the essays I wrote for tcj online got kind of lost in that site’s giant scroll…so I thought I’d reprint some of them here. This one is on Fumi Yushinaga’s All My Darling Daughters.

____________________________

Fumi Yoshinaga is not at her best in the short story form. In longer series, her weakness for glib psychoanalyzing can be overwhelmed by her virtues: sublime nonsense in Antique Bakery; a matchless feel for character interaction and development in Ooku.

In All My Darling Daughters, though, the tales get clipped off with pat endings and pat-er moralizing before Yoshinaga can plumb either nonsensical heights or emotional depths. The second story in this collection is perhaps the most painful example. A college teacher semi-reluctantly acquiesces to a series of blowjobs from a homely, obsessed student with serious self-esteem issues. He feels more and more guilty — but when he tries to turn their relationship into something less exploitative…she dumps him because he’s too nice! Isn’t that a goofy, unexpected plot twist? Yoshinaga seems to think so anyway. In fact, she’s so enamored of the clever reversal that she neglects to put actual people in the story. The scant efforts at individuation (the girl has big breasts! the guy has — oh, wait. He doesn’t have any distinguishing characteristics at all) serve only to emphasize the extent to which these aren’t people so much as gears grinding together in the service of a soft-core clockwork sentimentality.

That’s the story which really left a bad taste in my mouth, but a couple of the others also seemed vacuous and manipulated. In one, three childhood friends largely fail to fulfill their dreams; in another, a radiantly kind and generous woman loves the whole world so much she has trouble loving one man in particular, and so she…well, I won’t spoil the twist ending. Who am I to deprive you of the full weight of a thudding cliché?

For much of this book, in short, Yoshinaga seems to be on autopilot; writing throw-away plots for characters she hasn’t thought about. Which is a shame since, when she is engaged, she remains one of my favorite manga-kas. She becomes a different creator altogether when she’s dealing with the Yukiko and her mother Mari, who are featured in the first and last story and have walk-on parts in the rest.

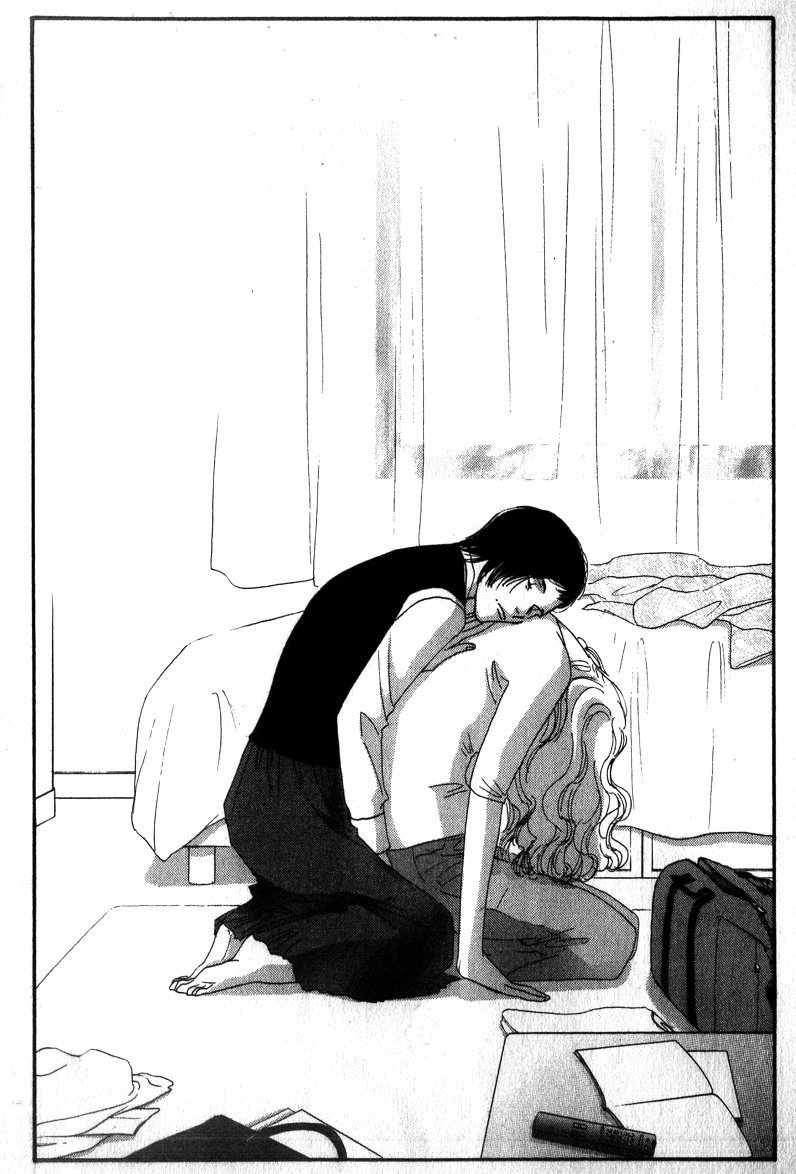

The first tale, in which Mari decides to marry a much younger man and Yukiko decides as a consequence to leave home, is constructed, not around a single irony or reversal, but instead through a series of quiet moments and incomplete but shimmering revelations. The last of these is somewhat overdetermined — but it’s rescued by the story’s final page, in which Yukiko sits on the floor, her head bent forward, while her mother spoons against her in a comforting hug.

Yoshinaga uses her spare lines and mastery of body design to great effect — the curtains and bed in the image seem almost to fade into nothing, concentrating the eye on the kneeling figures. Yukiko is in pale colors; Mari, on the other hand, is in a dark shirt and dark pants. Cupped together, Mari seems like an anchor — and also, with her newly cut hair, like a boy or a man. The position is itself almost sexual — an intimation echoed in the immediately preceding scene, which hinges on jealousy and reads like a break-up as much as a mother/daughter parting. Mari’s hand rests under her own head and against Yukiko’s spine; it’s a virtually hidden, but very intimate and tactile detail. Mari’s expression is relaxed and unreadable; she looks like she’s asleep. The picture is both eloquent and mysterious; you can see the love between the two women, but the exact components of that love — its sensuality, its history, who has needed to lean on who, and when, and how — remain private.

Yoshinaga uses her spare lines and mastery of body design to great effect — the curtains and bed in the image seem almost to fade into nothing, concentrating the eye on the kneeling figures. Yukiko is in pale colors; Mari, on the other hand, is in a dark shirt and dark pants. Cupped together, Mari seems like an anchor — and also, with her newly cut hair, like a boy or a man. The position is itself almost sexual — an intimation echoed in the immediately preceding scene, which hinges on jealousy and reads like a break-up as much as a mother/daughter parting. Mari’s hand rests under her own head and against Yukiko’s spine; it’s a virtually hidden, but very intimate and tactile detail. Mari’s expression is relaxed and unreadable; she looks like she’s asleep. The picture is both eloquent and mysterious; you can see the love between the two women, but the exact components of that love — its sensuality, its history, who has needed to lean on who, and when, and how — remain private.

If Yoshinaga sometimes seems indecently eager to wrap up character and narrative in a neat package, at her best she does the opposite. As Mari’s young husband says of Mari in the final chapter of the book, “knowing the history doesn’t mean her issues will disappear. Knowing, forgiving, and loving are all different things.” There is no key to Yukiko or Mari, no twist ending that will tell us who they are. In the book’s final panel, Mari laughs unexpectedly, and not only is it not entirely clear what she finds funny, we never see how Yukiko reacts. There’s a dignity in that; a sense, perhaps, that you need some measure of not knowing, if not for forgiveness, at least for love.