A few weeks ago Noah posted a link to an essay by Bert Stabler slamming the medium of art photography. Rankled by the dismissal of a fascinatingly diverse medium I agreed to write a rebuttal. However, rather than address the essay point by point, I’m addressing what I see as the fundamental flaw at the heart of Stabler’s essay, that the small, highly commercial subset of art photography that Stabler critiques is at all representative of the varied artistic power of photography by focusing on the work of several engaging contemporary artists who use photography in their practice.

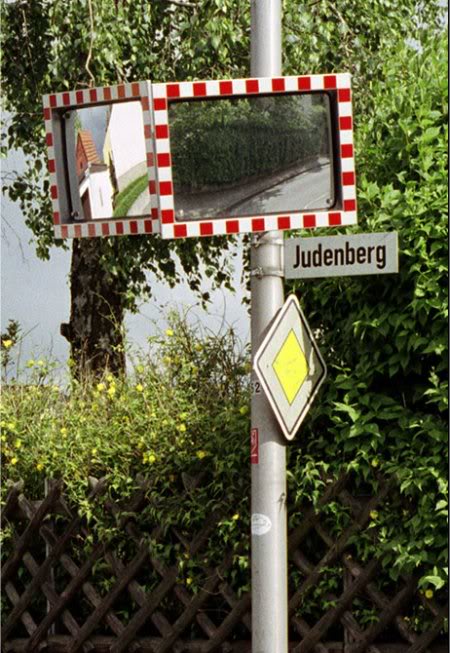

Susan Hiller’s work often focuses on the poetic systems behind the act of collecting, archiving and organising, perhaps the most striking of her ‘collection’ works is The J. Street Project. Encompassing three years of research, travel and photography, The J. Street Project is a massive collection of 303 photos documenting every street sign in Germany that contains the prefix Juden (Jew). Shot in a workmanlike fashion, the series is displayed in three formats; As a 606 page photo book of sequential photographs, as a 67 minute slide film, or as a monumental installation piece, pictured below.

While the individual photographs would appear as nothing more than a quirk, an oddity, it is the insistent mass and repetition of subject that gives this piece its incredible effect. Over and over, these mundane objects throw in to stark relief the dissonance between these German streets and the historical context of the country. Presented without comment, without drama, the audience is forced to fill the void of absence created by the work, projecting their cultural experiences in to the insistent work.

In the face of a modernity that demands constant efficiency and production, Alys’s Sleepers series forms a documentary of passive resistance. The work, comprised of 80 colour projector slides, depicts sleeper, both animal and human, engaging in an unusual relation to the urban construction.

Alys takes care to address the issue of the camera’s gaze in Sleepers as well, the subjects are always shot from low to the ground, or (or level with them in the case of bench sleepers), by joining his sleepers in such a way, Alys avoids what could have been a carousel of condescending ‘poverty porn’. Alys does not pity his sleepers, doesn’t look down on his subjects but lies with them, praising them for their ingenuity and their willingness to break with the social systems and rules of the modernised urban space.

Alys’s photographic vision in his other work cannot be ignored either. His photographic records of his performative and conceptual pieces is of particular note, here Alys excels at capturing and distilling the ‘defining image’ of a brief, ephemeral event. In ‘Turista’ we see this talent exemplified.

Here Alys strikes a comical figure, lanky, pale and absurd as he tries unsuccessfully to blend in to the line of trade workers in Mexico City. The picture poses a question and a humorous barb at the notion of the nomad artist, travelling between countries, gifting the people with their insights in to foreign cultures. Embodied and mocked by Alys, the notion becomes ridiculous, and we’re forced to ask ourselves, is the artist-nomad really a chameleonic nomad, able to fit in to any society and privy to mystic truths, or are they nothing more than a glorified tourist?

The camera has often been compared to a phallus, a weapon wielded by the photographer against subject. In the work of Jean Francois Lecourt that idea is taken to a delightfully absurd extreme.

The artist wields his camera as a gun and a gun as a camera, all targeted at his own nude body in an act of simultaneous destruction and creation.

Lecourt was inspired by old fairground games that still occasionally pop up around mainland Europe. In the game the participant is given a rifle and must shoot at a target mounted in the fairground stand, if they hit the bullseye, a camera automatically shoots a picture of them shooting the target.

Lecourt created a large, lightproof box to house a sheet of photosensitive paper, a kind of pinhole camera without the pinhole. He then stripped naked and fired a shot at his home made camera, simultaneously piercing the camera and the paper behind.

The resultant picture is a beautifully hazy, moody thing, recalling the dramatic light of a Noir film,. Lecourt’s pictures capture your eye, drawing you in with their strangeness. The eye’s registering of the depth of the photo is constantly baffled by the literal punctum of the gunshot hole, which seems to overlay the image like an abstract supernova, pulling the viewer’s eye constantly to the surface and reminding them of the object hood of the photograph.

The wit of Lecourt’s technique is wonderful to me as well, the idea of the nude male artist wielding the phallus of the gun against the phallus of the camera in an act of symbolic suicide that mocks the narcissistic romance of the self destructive artist, the artist shooting himself in both senses of the word and ending not with oblivion, but with another image of his own body.

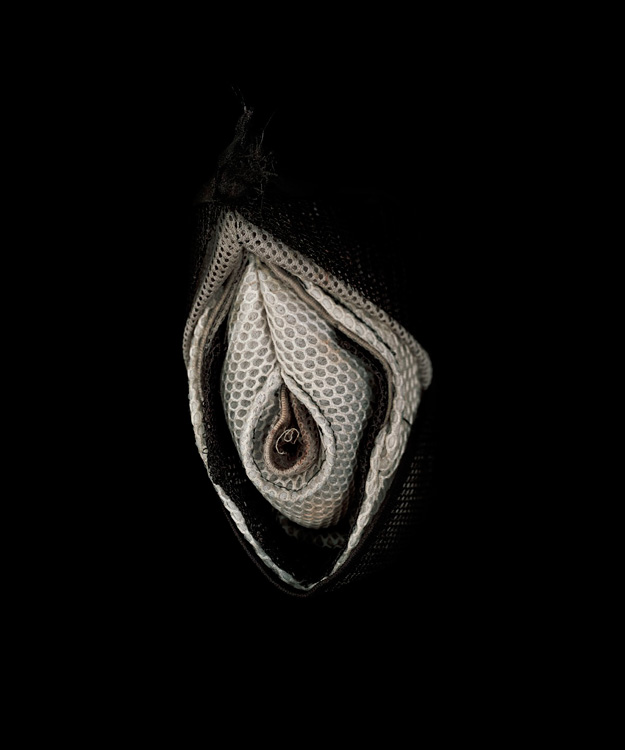

Danny Treacy’s work addresses the things we leave behind, travelling to out of the way or marginalised areas, the kind of places where people go to be alone and unseen together. Treacy collects trophies of abandoned clothing found in these areas, turning them in to sculptural subjects for his photographs that harness the suggestive, intimate untold histories behind the abandoned clothes to create a haunting mood that is as sensual and beautiful as it is haunting and inexplicably frightening.

In ‘Those’, Treacy’s first series, the artist created a series of organically suggestive sculptures using found fabric. These sculptures are all what Danny calls ‘protuberances’, the things that stick out from us, that enter the world and, through their orifice like openings, invite the world to enter them, to gaze in to the soft folds of their innards. Named as Those, they become empty, out of place things, without noun, signs awaiting an object, as alien as they are enticing.

The bizarre, erotically charged organs are shot intimately, close up against a plain black background, leaving the eye to wander over the sensual surfaces of the soft fabrics that Treacy employs. Through the forensic eye of Treacy’s camera, the erotically charged sculptures discharge their intimate history and morph in to a proxy of the human flesh they once covered. One wishes they could reach out, to touch the sculptures, to reach inside and feel them.

Treacy’s other series, ‘Them’, continues the artist’s obsession with the discarded skins of our clothes, the ‘Them’ are different however, the name itself recalls horror movies of bygone eras, and the ‘Them’ indeed are a kind of monster. Constructed from mended and sewn together pieces of clothing, the Them become sad, tragic figures, haunting and frightening as they loom from the darkness, filled with the body of the artist himself, who claims to feel a kind of protection and comfort from within the shambolic, anonymous suits he constructs, a connection with an intimate history of the abandoned garments in to which he has breathed a new and unnatural life. To us on the outside though, the figures are threatening presences, each unnameable stain evoking the hidden histories of the things we carelessly abandon, reminding us that every piece of clothing was witness to the fate of their owners, whatever that may be.